American Choral Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

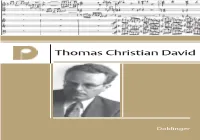

Thomas Christian David

Thomas Christian David Foto Seite 1: Kobé, Seite 3: Heinz Moser Notenbeispiel Seite 1: Thomas Christian David, Konzert für Orgel und Orchester Redaktion: Dr. Christian Heindl H/8-2007 d INFO-DOBLINGER, Postfach 882, A-1011 Wien Tel.: +43/1/515 03-33,34 Fax: +43/1/515 03-51 E-Mail: [email protected] 99 306 website: www.doblinger-musikverlag.at Doblinger Inhalt / Contents Biographie . 3 Biography . 4 Werke bei / Music published by Doblinger INSTRUMENTALMUSIK / INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC Flöte / Flute . 5 Klarinette / Clarinet . 5 Violine / Violin . 5 Klavier / Piano . 5 Orgel / Organ . 5 Violine und Klavier / Violin and piano . 6 Violoncello und Klavier / Cello and piano . 6 Duos und Kammermusik für Blasinstrumente / Duos and chamber music for wind instruments . 6 Duos und Kammermusik für Streichinstrumente / Duos and chamber music for string instruments . 7 Kammermusik für Gitarre / Chamber music for guitar . 8 Duos und Kammermusik für gemischte Besetzung / Duos and chamber music for mixed instruments . 8 Soloinstrument und Orchester / Solo instrument and orchestra . 10 Blasorchester / Wind orchestra . 11 Streichorchester / String orchestra . 12 Orchester / Orchestra . 12 VOKALMUSIK / VOCAL MUSIC Gesang und Klavier / Solo voice and piano . 12 Gesang und Orchester / Solo voice and orchestra . 13 Gemischter Chor a cappella / Unaccompanied choral music . 14 Gemischter Chor mit Begleitung / Accompanied choral music . 14 Kantate, Oratorium / Cantata, Oratorio . 15 Oper / Opera . 15 Abkürzungen / Abbreviations: L = Aufführungsmaterial leihweise / Orchestral parts for hire UA = Uraufführung / World premiere Nach den Werktiteln sind Entstehungsjahr und ungefähre Aufführungsdauer angegeben. Bei Or- chesterwerken folgt die Angabe der Besetzung der üblichen Anordnung in der Partitur. Käufliche Ausgaben sind durch Angabe der Bestellnummer links vom Titel gekennzeichnet. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1961-1962

Music Shed — Tanglewood Lenox, Massachusetts Thursday, August 2, 1962, at 8:00 For the Benefit of the Berkshire Music Center THE BOSTON POPS ARTHUR FIEDLER, Conductor Soloist EARL WILD, Piano PROGRAM *The Stars and Stripes Forever Sousa *Suite from "Le Cid" Massenet Castiliane — Aragonaise — Aubade — Navarraise #Mein Lebenslauf ist Lieb' und Lust, Waltzes Josef Strauss Pines of Rome Respighi I. The Pines of the Villa Borghese II. The Pines near a Catacomb III. The Pines of the Janiculum IV. The Pines of the Appian Way Intermission *Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra Gershwin I. Allegro II. Adagio; Andante con moto III. Allegro agitato Soloist: Earl Wild *Selection from "West Side Story" Bernstein I Feel Pretty — Maria — Something's Coming — Tonight — One Hand, One Heart — Cool — A-mer-i-ca Mr. Wild plays the Baldwin Piano Baldwin Piano *RCA Victor Recording Special Event at Tanglewood Thursday, August 23 A GALA EVENING of Performances by the Students For the Benefit of the Berkshire Music Center ORDER OF EVENTS 4 :00 Chamber Music in the Theatre 5 :00 Music by Tanglewood Composers in the Chamber Music Hall 6:00 Picnic Hour 7 :00 Tanglewood Choir on the Main House Porch 8 :00 The Berkshire Music Center Orchestra Concert in the Shed In Mahler's Third Symphony, with the Festival Chorus and Florence Kopleff, Contralto Conductor—Richard Burgin Admission tickets . (All seats unreserved except boxes) $2.50 — Box Seats $5.00 Grounds open for admission at 3 :00 p.m. REMAINING FESTIVAL CONCERTS (The final concerts of Charles Munch as Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra) EVENINGS — 8 :00 P.M. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958, Subscription

*l'\ fr^j BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 G> X will MIIHIi H tf SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1957-1958 BAYARD TUCEERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON, JR. HERBERT 8. TUCEERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mast. LA fayette 3-5700 SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-1958 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Alvan T. Fuller John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Palfrey Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Charles H. Stockton C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D. -

2017 Convention Schedule

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 4 2:00PM – 5:00PM Board of Directors Meeting Anacapa 6:00PM - 9:00PM Pre-Conference Dinner & Wine Tasting Villa Wine Bar 618 Anacapa Street, Santa Barbara 7:00PM – 10:00PM Opera Scenes Competition Rehearsal Grand Ballroom THURSDAY, JANUARY 5 8:00AM – 5:00PM Registration Grand Foyer 9:00AM – 5:00PM EXHIBITS Grand Foyer 9:00AM – 9:30AM MORNING COFFEE Grand Foyer Sponsored by the University of Colorado at Boulder College of Music 9:30AM-10:45AM Sierra Madre The 21st Century Way: Redefining the Opera Workshop Justin John Moniz, Florida State University Training programs have begun to include repertoire across varying genres in order to better equip young artists for prosperous careers in today’s evolving operatic canon. This session will address specific acting and movement methods geared to better serve our current training modules, offering new ideas and fresh perspectives to help redefine singer training in the 21st century. Panelists include: Scott Skiba, Director of Opera, Baldwin Wallace Conservatory; Carleen Graham, Director of HGOco, Houston Grand Opera; James Marvel, Director of Opera, University of Tennessee-Knoxville; Copeland Woodruff, Director of Opera Studies, Lawrence University. 11:00AM-12:45PM Opening Ceremonies & Luncheon Plaza del Sol Keynote Speaker: Kostis Protopapas, Artistic Director, Opera Santa Barbara 1:00PM-2:15PM The Janus Face of Contemporary American Opera Sierra Madre Barbara Clark, Shepherd School of Music, Rice University The advent of the 21st century has proven fertile ground for the composition -

THE NEW YORK CHAMBER SOLOISTS CHARLES BRESSLER, Tenor ALBERT FULLER, Harpsichord MELVIN KAPLAN, Oboe GERALD TARAK, Violin YNEZ LYNCH, Viola ALEXANDER KOUGUELL, Cello

1964 Eighty-sixth Season 1965 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Second Program Second Annual Chamber Arts Series Complete Series 3446 THE NEW YORK CHAMBER SOLOISTS CHARLES BRESSLER, Tenor ALBERT FULLER, Harpsichord MELVIN KAPLAN, Oboe GERALD TARAK, Violin YNEZ LYNCH, Viola ALEXANDER KOUGUELL, Cello TUESDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 17, 1964, AT 8 :30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Cantata No. 72, "Was gleicht dem Adel wahrer Christen," for Tenor, Oboe, and Continuo TELEMANN Aria Recitative Aria Sonata in A major for Violin and Viola HAYDN Allegro moderato Adagio Tempo di minuetto *Concert Royal No. 4 for Oboe, Violin, Viola, Cello, and Harpsichord COUPERIN Prelude Allemande Courante fran~oise Courante a l'italiene Sarabande Rigaudon Forlane INTERMISSION * Decca Records A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS Quartet in F major, K. 370, for Oboe, Violin, Viola and Cello MOZART Allegro Adagio Rondo Cantata, "Crudel tiranno Amor," for Tenor, Strings, and Harpsichord Aria: Crudel tiranno Amor Recitative: Ma tu mandi al mio core Aria: 0 dolce mia speranza R ecitative : Senza te, dolce spene Aria: 0 cara spene Members of the New York Chamher Soloists not appearing in this concert include: Adele Addison, Soprano; Samuel Baron, Flute; Isidore Cohen, Violin; Julius Levine, Double Bass; and Harriet Wingreen, Piano. Forthcoming Presentations in Hill Auditorium NOVEMBER 20 Die Fledermaus (Strauss) NEW YORK CITY OPERA COMPANY 22 Merry Widow (Lehar) NEW YORK CITY OPERA COMPANY (2 :30 P.M.) 22 Faust (Gounod) NEW YORK CITY OPERA COMPANY JANUARY 20 tSEGOVIA, Guitarist 26 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist 30 BERLIN PHILHARMONIC, HERBERT VON KARAJAN, Conductor FEBRUARY 8 MINNEAPOLIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, STANISLAW SKROWACZEWSKI, Conductor 14 *PARIS CHAMBER ORCHESTRA 23 POLISH MIME THEATRE 27 *NETHERLANDS CHAMBER CHOIR MARCH 1 ROSALYN TURECK, Pianist 7 *CHICAGO LITTLE SYMPHONY 12 ROBERT MERRILL, Baritone 30 *SOLISTI Dr ZAGREB APRIL 3 NATIONAL BALLET OF CANADA 14 To be announced. -

Lps-Vocal Recitals All Just About 1-2 Unless Otherwise Described

LPs-Vocal Recitals All just about 1-2 unless otherwise described. Single LPs unless otherwise indicated. Original printed matter with sets should be included. 4208. LUCINE AMARA [s]. RECITAL. With David Benedict [pno]. Music of Donaudy, De- bussy, de Falla, Szulc, Turina, Schu- mann, Brahms, etc. Cambridge Stereo CRS 1704. $8.00. 4229. AGNES BALTSA [ms]. OPERA RECITAL. From Cenerentola, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, La Favorita, La Clemenza di Tito , etc. Digital stereo 067-64-563 . Cover signed by Baltza . $10.00. 4209. ROLF BJÖRLING [t]. SONGS [In Swedish]. Music of Widéem, Peterson-Berger, Nord- qvist, Sjögren, etc. The vocal timbre is quite similar to that of Papa. Odeon PMES 552. $7.00. 3727. GRACE BUMBRY [ms]. OPERA ARIAS. From Camen, Sappho, Samson et Dalila, Dr. Frieder Weissmann and Don Carlos, Cavalleria Rustican a, etc. Sylvia Willink-Quiel, 1981 Deut. Gram. Stereo SLPM 138 826. Sealed . $7.00. 4213. MONTSERAAT CABALLÉ [s]. ROSSINI RARITIES. Orch. dir. Carlo Felice Cillario. From Armida, Tancredi, Otello, Stabat Mater, etc. Rear cover signed by Caballé . RCA Victor LSC-3015. $12.00. 4211. FRANCO CORELLI [t] SINGS “GRANADA” AND OTHER ROMANTIC SONGS. Orch. dir Raffaele Mingardo. Capitol Stereo SP 8661. Cover signed by Corelli . $15.00. 4212. PHYLLLIS CURTIN [s]. CANTIGAS Y CANCIONES OF LATIN AMERICA. With Ryan Edwards [pno]. Music of Villa-Lobos, Tavares, Ginastera, etc. Rear cover signed by Curtin. Vanguard Stereolab VSD-71125. $10.00. 4222. EILEEN FARRELL [s]. SINGS FRENCH AND ITALIAN SONGS. Music of Respighi, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Debussy. Piano acc. George Trovillo. Columbia Stereo MS- 6524. Factory sealed. $6.00. -

Books About Music

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS BOOKS ABOUT MUSIC Biographies & Critical Studies of Composers & Musicians Music History & Criticism Musical Instruments Opera & Dance Reference Works, Bibliographies, Catalogues, &c. 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA [email protected] Telephone 516-922-2192 www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website at www.lubranomusic.com by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to ensure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. New York State sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. -

Only Performers Are Included Through the 1980-1981 Season

*Only performers are included through the 1980-1981 season. Both performers and repertoire are included beginning with the 1981-1982 season. PRESTIGE CONCERTS AT 8:30 P.M. IN THE LITTLE THEATRE OF THE COLUMBUS GALLERY OF FINE ARTS EXCEPT WHEN NOTED: 1948-1949 1948 November 29 (afternoon & eve) Walden String Quartet, Resident at the University of Illinois December 22 Walden String Quartet & Donald McGinnis, clarinet December 29 Ernst von Dohnanyi, piano 1949 January 13 and February 8 Walden String Quartet March 11 Walden String Quartet & Evelyn Garvey, piano 1949-1950 1949 December 14 Walden String Quartet 1950 January 9 Walden String Quartet February 11 Frances Magnes, violin & Malcolm Frager, piano March 13 Walden String Quartet March 30 Ernst von Dohnanyi, piano April 5 Walden String Quartet & Donald McGinnis, clarinet May 8 Walden String Quartet & Evelyn Garvey, piano 1950-1951 1950 November 15 Roland Hayes, tenor 1951 February 7 Nell Schelky Tangeman, soprano & Merrill Brockway, piano March 3 Frances Magnes, violin & David Garvey, piano 1951-1952 1951 October 18 Roland Hayes, tenor & Reginald Boardman, piano November 3 Soulima Stravinsky, piano (son of Igor) December 4 Berkshire String Quartet, Resident at Indiana University 1952 January 10 Frances Magnes, violin & David Garvey, piano February 9 David Garvey, piano March 8 Berkshire String Quartet 1952-1953 1952 October 27 Roland Hayes, tenor & Reginald Boardman, piano November 20 Juilliard String Quartet December 8 Luigi Silva, cello & Joseph Wolman, piano 1953 January 24 Beveridge -

Universiv Microtlms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note w ill appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Hugo Distler (1908-1942)

HUGO DISTLER (1908-1942): RECONTEXTUALIZING DISTLER’S MUSIC FOR PERFORMANCE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by Brad Pierson A dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Geoffrey P. Boers, Chair Giselle Wyers Steven Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music © Copyright 2014 Brad Pierson ii Acknowledgements It has been an absolute joy to study the life and music of Hugo Distler, and I owe a debt of gratitude to many people who have supported me in making this document possible. Thank you to Dr. Geoffrey Boers and Dr. Giselle Wyers, who have served as my primary mentors at the University of Washington. Your constant support and your excellence have challenged me to grow as a musician and as a person. Thank you to Dr. Steven Morrison and Dr. Steven Demorest for always having questions and forcing me to search for better answers. Joseph Schubert, thank you for your willingness to always read my writing and provide feedback even as you worked to complete your own dissertation. Thank you to Arndt Schnoor at the Hugo Distler Archive and to the many scholars whom I contacted to discuss research. Your thoughts and insights have been invaluable. Thank you to Jacob Finkle for working with me in the editing process and for your patience with my predilection for commas. Thank you to my colleagues at the University of Washington. Your friendship and support have gotten me through this degree. Finally, thank you to my family. You have always supported me in everything I do, and this journey would not have been possible without you. -

Johann Nepomuk David Und Seine Leipziger Zeit1 Maren Goltz

Johann Nepomuk David und seine Leipziger Zeit1 Maren Goltz Vorbemerkung Dass die Aufarbeitung der NS-Vergangenheit von Hochschulen und Universitäten nach wie vor ein schwieriges und zum Teil hoch emotio- nales Forschungsfeld ist, zeigt nicht nur im Großen die heftig geführte Auseinandersetzung auf dem Frankfurter Historikertag 1998, sondern im Kleinen auch das Leipziger Symposium zu Johann Nepomuk David. Während in Frankfurt der Aufsehen erregenden Sektion „Historiker in der NS-Zeit – Hitlers willige Helfer?“ die Vergangenheit einiger Grün- derväter der BRD-Geschichtswissenschaft thematisiert wurde2 und die Feststellung, es habe zum Teil „ein[en] Verlust der Substanz“ gegeben und einzelne Vertreter des Faches seien gar „Vordenker der Vernichtung“ gewesen, massive Empörung im Publikum hervorrief, fiel in Leipzig insbesondere die Atmosphäre nonverbaler bis hin zu offen artikulier- ter Ablehnung gegenüber quellenorientierten Forschungsergebnissen auf. Dass sich die (mittlerweile längst emeritierten) Schüler noch immer stark mit ihren Lehrern – und im Falle Leipzigs sogar deren ehemali- gen Kollegen (!) – identifizieren und sich persönlich angegriffen fühlen, wenn Untersuchungen zu deren Haltung im Nationalsozialismus prä- sentiert werden, ist möglicherweise gerade in dieser Generation – offen- bar bis heute im Osten wie im Westen – besonders ausgeprägt und stellt für sich betrachtet ein eigenes, hochinteressantes Forschungsthema dar. Dass sich im Nachgang im hochschuleigenen MT-Journal allenfalls ein 1 Bei den folgenden Ausführungen handelt es sich um überarbeitete Teile aus meiner Schrift Musikstudium in der Diktatur. Das Landeskonservatorium der Musik / die Staatliche Hochschule für Musik Leipzig in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933– 1945, Stuttgart 2013. 2 Volker Ullrich, Späte Reue der Zunft. Endlich arbeiten die deutschen Historiker die braune Vergangenheit ihres Faches auf, in: Die Zeit, 17.