GOLD, SILVER and COPPER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historical Origins of the Safe Haven Status of the Swiss Franc1

Aussenwirtschaft 67.2 The historical origins of the safe haven status of the Swiss franc1 Ernst Baltensperger and Peter Kugler University of Berne; University of Basel An empirical analysis of international interest rates and of the behavior of the exchange rate of the Swiss franc since 1850 leads to the conclusion that World War I marks the origin of the strong currency and safe haven status of the Swiss franc. Before World War I, interest rates point to a weakness of the Swiss currency against the pound, the guilder and French franc (from 1881 to 1913) that is shared with the German mark. Thereafter, we see the pattern of the Swiss interest rate island develop and become especially pronounced during the Bretton Woods years. Deviations from metallic parities confirm these findings. For the period after World War I, we establish a strong and stable real and nominal trend appreciation against the pound and the dollar that reflects, to a sizeable extent, inflation differentials. JEL codes: N23 Key words: Swiss franc, safe haven, Swiss interest island, deviation from metallic parity, real and nominal appreciation 1 Introduction The Swiss franc is commonly considered a “strong” currency that serves as a “safe haven” in crisis periods. This raises the question of when the Swiss franc took on this property. Is it associated with the flexible exchange rate regime in place since 1973, or was it already in existence before then? Was the Swiss franc a “weak” currency even in the first decades after its creation in 1850? In order to analyze these questions, we need a definition of a strong currency and its properties. -

1935 Time Capsule Part 3

Money Currency is small but holds value beyond the monetary. Money commemorates events, represents the past or heritage. Such items were included in the 1935 Time Capsule. Texas Centennial Half Dollar This was a commemorative coin was minted in honor of Texas’s independence from Mexico in 1836. The coin depicts an eagle on a branch in front of the Lone Star. Below the eagle reads “HALF DOLLAR.” On the reverse is the goddess Victory with wings spread over the Alamo. The Six Flags of Texas fly over her head. Below Victory reads “REMEMBER THE ALAMO.” The coin was minted from 1934 to 1938. Size of the coins were 2” diameter. There were three Centennial Half Dollars in the time capsule, each one with a letter or envelope identifying the donor. At the opening of the 1905 City Hall Time Capsule on January 27, 1935, several Texas Centennial Half Dollars were auctioned off by Sheriff Louis Lowe. Some of these coins and their letters of authentication were added to the 1935 City Hall Time Capsule. The first auctioned Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased by J.E. Alhgreen. The coin is accompanied by a letter of authenticity by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. Luhn Post No. 39 letterhead and matching envelope. Coin Front Coin Back 32 Letter Front 33 Letter Back 34 The second Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased at the same auction by E.E. Rummel. Shown below are the paperwork establishing the authenticity of the purchase by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

Optimal Currency Shares in International Reserves: the Impact of the Euro and the Prospects for the Dollar

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Papaioannou, Elias; Portes, Richard; Siourounis, Gregorios Working Paper Optimal currency shares in international reserves: the impact of the euro and the prospects for the dollar ECB Working Paper, No. 694 Provided in Cooperation with: European Central Bank (ECB) Suggested Citation: Papaioannou, Elias; Portes, Richard; Siourounis, Gregorios (2006) : Optimal currency shares in international reserves: the impact of the euro and the prospects for the dollar, ECB Working Paper, No. 694, European Central Bank (ECB), Frankfurt a. M. This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/153128 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an -

The Costs of Dollarization; a Central Banker’S View

The costs of dollarization; a central banker’s view Speech by Jeanette R. Semeleer, President of the Centrale Bank van Aruba (CBA), at the Symposium on “The advantages and disadvantages of Dollarization”, organized by the Council of Advice of St. Maarten, March 26, 2015. Members of Parliament, Ministers, Members of the Council of Advice and other distinguished guests, good evening. 1. Introduction First of all, allow me to express words of gratitude to the Council of Advice for the invitation to address you on the topic “The advantages and disadvantages of Dollarization”. I am truly honored and privileged to be here on this beautiful island (I should come here more often) and to contribute to the ongoing debate of dollarization in St. Maarten. Page 1 of 21 We all probably agree that dollarization is not an easy topic to debate on, but I hope when we leave the room tonight that some practical tools have been provided to facilitate the discussions. If this debate moves some time in the future towards a political decision that involves a change in the current exchange rate regime, extensive knowledge and practical experience are needed to choose the best policy for managing the exchange rate, which is a key instrument towards achieving macro- economic goals and maintaining financial stability. Tonight my speech will primarily focus on the costs of dollarization within the context of full dollarization. By full dollarization, I refer to a situation in which a country formally adopts a currency of another country—most commonly the U.S. dollar—as its legal tender.1 2. -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

Precious Metals US SILVER COINS VALUE GUIDE

Precious Metals US SILVER COINS VALUE GUIDE – coins dated 1964 and earlier Page 1 Value shown is the (US dollar*) value of the silver found in each silver coin Silver price $2.75 $3.00 $3.25 $3.50 $3.75 $4.00 $4.25 $4.50 $4.75 $5.00 $5.25 $5.50 $5.75 $6.00 $6.50 $7.00 $7.50 per troy ounce: Dime – 10 c .19 .21 .23 .25 .27 .28 .30 .32 .34 .36 .37 .39 .41 .43 .47 .50 .54 dated 1964 or before 7.2% oz Quarter – 25 c .49 .54 .58 .63 .67 .72 .76 .81 .85 .90 .95 .99 1.04 1.08 1.17 1.26 1.35 dated 1964 or before 18% oz Half Dollar – 50 c .99 1.08 1.17 1.26 1.35 1.44 1.53 1.62 1.71 1.80 1.89 1.98 2.07 2.16 2.34 2.52 2.70 dated 1964 or before 36% oz $1.00 face value of 1.98 2.16 2.34 2.52 2.70 2.88 3.06 3.24 3.42 3.60 3.78 3.96 4.14 4.32 4.68 5.04 5.40 mixed dimes, quarters or halves – dated 1964 or before - 72% oz Silver dollars 2.11 2.31 2.50 2.69 2.88 3.08 3.27 3.46 3.65 3.85 4.40 4.23 4.42 4.62 5.00 5.39 5.77 1935 or before 77% oz Most US dimes (and larger silver coins) dated before 1965 are made of 90% silver and 10% copper. -

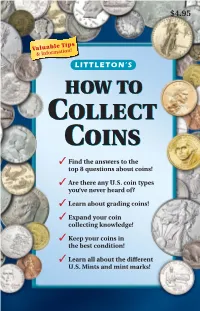

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

E-Gobrecht Volume 5, Issue 9

Liberty Seated The E-Gobrecht Collectors Club 2009 Volume 5, Issue 9 The Electronic Newsletter of the LIBERTY SEATED COLLECTORS CLUB September 2009 (Whole # 55) LSCC Annual Meeting – Los Angeles ANA, August 6, 2009 What’s Inside this issue? Notes from the LSCC Secretary-Treasurer, Auction News 2-3 Len Augsburger by Jim Gray Question of the Month 4,18 I counted over forty attendees, The Gobrecht Journal by Paul Kluth although I heard another count Award, which is given each 25 Historical Collections… 5-7 which put the number at fifty- issues for the best article in that By Gerry Fortin eight. period, was awarded to Dick Os- A Bogus 1890 Dime 7 By Bert Schlosser The officers will remain burn for his seated half dollar the same for the 2009-2010 club rarity analysis published in GJ 1853-O Dime Shattered 8 and Unshattered Die year which begins on Septem- #76. John McCloskey noted that By Jason Feldman ber 1st. Osburn’s approach for rarity Medal Alignment in the 9-12 The preliminary treas- analysis by denomination has Liberty Seated Series urer’s report was issued, show- since been adopted by other au- By Len Augsburger ing a surplus for the year of thors in the Journal. 1924 Beistle Advertise- 12 about $900. Printing and post- Al Blythe was inducted ment in The Numismatist age expenses were down from into the LSCC Hall of Fame. Pre- Two Unusual Seated 13 last year, reflecting the larger sent to accept the award was Dollars page count used last year in his daughter, Gail. -

Silver Coinage Under the Emperor Nero

DEBASEMENT OF THE Silver Coinage Under the Emperor Nero BY T. LO UIS COMPARETTE, Ph. D. NEW YORK 1914 V JL43359 1 ONE HUNDREDS COPIES REPRINTED FROM THlE AMoERICAN JOURNAL OF N UMISAFATIUS VOLUME XLVII " . " . "."" " " DEBASEMENT OF THE SILVER COINAGE UNDER THE EMPEROR NERO. BY T. LOUIS COMPARETTE, PH. D. The paucity of extant records pertaining to the coinage of Rome during the first century of the empire makes it very difficult to reach an understanding of the many changes which the coins themselves dis- close took place in that period, extending from the first issue of gold at Rome by Julius Caesar to the reign of Nero, or between B. C. 49 and A. D. 62, the probable date of important legislation in the principate of the latter emperor. This may be accounted for largely by the fact that readers of the historians and other writers were so completely removed from participation in the affairs of government that important histori- cal facts regarding legislation and administration did not interest them. Government had become a personal affair and history took on the color of personal gossip. But the lack of records may also be due, and prob- ably is chiefly due, to the fact that the alterations in the coins were of purely administrative origin, and thus there were no vital legislative enactments to record. However, currency matters must have frequently occupied the at- tention of the senate and imperial council during the first century of the empire; for the new imperial coinage laws would certainly require numerous modifications to adjust the currency to the needs of an empire whose far-flung dominions presented the greatest diversity of trade and commerce, and whose local coinages had to be taken into consideration by the framers or reformers of the imperial system. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 Dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive)

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive) SUBJECT: Sales of Coins, Bullion, or Legal Tender REFERENCE: IC 6-2.5-3-5; IC 6-2.5-4-1; 45 IAC 2.2-4-1; IC 6-2.5-5-47 DISCLAIMER: Information bulletins are intended to provide nontechnical assistance to the general public. Every attempt is made to provide information that is consistent with the appropriate statutes, rules, and court decisions. Any information that is inconsistent with the law, regulations, or court decisions is not binding on the department or the taxpayer. Therefore, the information provided herein should serve only as a foundation for further investigation and study of the current law and procedures related to the subject matter covered herein. SUMMARY OF CHANGES Other than nonsubstantive, technical changes, this bulletin is revised to clarify that sales tax exemption for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender applies to coins, bullion, or legal tender that would be allowable investments in individual retirement accounts or individually-directed accounts, even if such coins, bullion, or legal tender was not actually held in such accounts. INTRODUCTION In general, an excise tax known as the state gross retail (“sales”) tax is imposed on sales of tangible personal property made in Indiana. However, transactions involving the sale of or the lease or rental of storage for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender are exempt from sales tax. Transactions involving the sale of coins or bullion are exempt from sales tax if the coins or bullion are permitted investments by an individual retirement account (“IRA”) or by an individually-directed account (“IDA”) under 26 U.S.C.