Blake's Atlantis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our August Club Night

Our August club night The house band Breakthru' opened up the evening as usual, we also saw them play last Wednesday at a nearby Club in Molesey where they had a chance to play a few non Shadows hits and explore some different sounds. I was first up to get it over and done with, not too good for me as I did not have much pratice and am only just getting full feeling back into my fingers. The Players Steve J – Apache, Wonderful Land Tony Knight – Foot Tapper, Cavatina (Theme from The Deer Hunter) Mike Norris – Theme from Shane, Mustang Bob Withrington – Rounding the Cape, Return to the Alamo John Cade – Shindig, Mountains of the Moon Alan Tarrant – Atlantis, Theme for Young Lovers Keith Humphries (visiting from South Africe) - The Savage, Peace Pipe John Bell – Cosy, Shadoogie (with Mark Winter on Drums) J. J. (visiting from USA) – Carolina on my Mind, Start the day Early Eugene McGuigan - Peace Pipe, Wonderful Land Robin Surridge with Jim on Rhythm – Lost City, Its a Mans World Stuart Osborne – Man of Mystery, Frightened City Gareth Morgan – Spring is nearly Here, Frightened City The Rock and Roll Section This featured Mark Winter on Drums, Alan Tarrant on Lead/Rhythm, Stuart Osborne on Lead/Vocals, Jim on Rhythm, Bob Withrington on Bass and Bob Dore on Keyboards – They played a selection of tunes including No Way to Go, Great Balls of Fire and Its Alright Mama. Barry Gibson took over Lead with Keith West on Vocals for Wicked Game, Folson Prison Blues and Little Sister. -

Echo Settings

ELENCO SETTAGGI ECHO PER BASI SHADOWS & CLIFF RICHARD - A CURA DI GIGI CERESA TITOLO CD BASI TRACK Q2 / 20 GT/PLUS Aggiornato 23.03.07 Titolo del CD n. Echo set: Echo set: A Adios Muchachos Io Suono Shadows v. 4 14 Africa UB Hank 05 2 0-36 32 A Groovy Kind of Love Marvin Mastertrax 9 0-36 32 A Girl Like You Shadows Workout 8+ 16-17 1-66 A Hard Day’s Night Marvin Mastetrax 1 0-38 A Kiss From A Rose Marvin Mastertrax 3 0-36 All Day Shadows Workout 6+ 22 1-65 All Day Lead Wanted 1 12 1-65 Another Night Shadows Workout 6+ 14 0-54 A Place in The Sun Shadows Workout 2+ 10 1-64 A Sigh Shadows Workout 1+ 18 0-01 01 A Tall, A tall Dark Lead Wanted Acoustic 6 A Thing Of Beauty Shadows Workout 6+ 20 0-33 A Whiter Shade Of Pale Lead Wanted 1 14 0-27 Adios Muchachos UB Hank 02 22 0-01 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Marvin Mastertrax 13 0-36 Albatross UB Hank 04 9 0-00 00 Alentejo Shadows Workout 5+ 14 1-66 Alentejo Lead Wanted Acoustic 12 Alice in Sunderland Shadows Workout 4+ 20 1-65 All I Ask Of You Casting A Shadow 5 0-33 All I Ask Of You Io Suono Shadows v. 6 14 0-40 Apache UB Hank 01 1 0-16 16 Apache Casting A Shadow 20 0-16 Apache Io Suono Shadows v. 1 12 0-16 Apache That Sound ! v. -

1 Victor Rust

VICTOR RUST: THE SHADOWS RECORDING CATALOGUE AN EXTENDED REVIEW Malcolm Campbell Victor Rust, The Shadows Recording Catalogue . Lulu Publications, September 2011. ISBN 978-0-9567384-1-7, 572pp. A download is available for purchase. In my review of Victor Rust’s book in Pipeline 88 (Spring 2012) 54–56 I complimented the element of musical analysis, but found practically nothing else to commend it. I decided when I submitted the review that it was better on balance with the space at my disposal to single out the main problem areas and furnish representative examples of each. The purpose of these pages of further personal reflections is to deal more extensively with the rampant plagiarism and the mountain of inadequately researched and poorly digested material that pervades the work. I won’t rehearse here the particulars of the Pipeline review. I am happy however to furnish anyone interested in the fuller picture with a scan of it via email, just contact me direct at [email protected] I should make it clear at the outset that it is a matter of great regret to me that my judgement of this book has turned out to be so severe. Its outer appearance suggested that we might expect a substantial contribution to our understanding of the group’s rich musical output, something that built constructively upon the foundations laid with immense patience, effort, skill and dedication by various researchers over a number of decades. That such an expectation is far from being met on any reasonable reckoning is the contention of this paper. -

Book7-File06

1963 EP 26: February 1963 The Shadows • Out Of The Shadows, Columbia SEG 8218 Mono / ESG 7883 Stereo EP 27: March 1963 Cliff Richard and The Shadows • Time For Cliff And The Shadows , Columbia SEG 8228 Mono / ESG 7887 Stereo EP 28: March 1963 The Shadows • Dance On With The Shadows, Columbia SEG 8233 Mono EP 29: May 1963 Cliff Richard and (1 track of 4) The Shadows • Holiday Carnival , Columbia SEG 8246 Mono / ESG 7892 Stereo EP 30: May 1963 The Shadows • Out Of The Shadows No. 2, Columbia SEG 8249 Mono / ESG 7895 Stereo EP 31: June 1963 Cliff Richard and The Shadows • Hits From Summer Holiday , Columbia SEG 8250 Mono / ESG 7896 Stereo CR 3: September 1963 • More Hits From Summer Holiday , Columbia SEG 8263 Mono / ESG 7897 Stereo EP 32: September 1963 The Shadows • Foot Tapping With The Shadows, Columbia SEG 8268 Mono Catalogue number notwithstanding, this EP was actually released a couple of weeks before the preceding EP, ‘Foot Tapping …’ EP 33: September 1963 The Shadows • Los Shadows, Columbia SEG 8278 Mono EP 34: October 1963 Cliff Richard and (3 tracks of 4) The Shadows • Cliff’s Lucky Lips , Columbia SEG 8269 Mono Released in October despite the assigned catalogue number; held back from September release, reason unknown. CR 4: November 1963 • Love Songs , Columbia SEG 8272 Mono / ESG 7900 Stereo EP 35: December 1963 The Shadows • Shindig With The Shadows, Columbia SEG 8286 Mono 110 EP 26 February 1963 The Shadows ‘Out Of The Shadows’ Columbia SEG 8218 Mono / ESG 7883 Stereo ============ EP 30 May 1963 The Shadows ‘Out Of The Shadows No. -

Atlantis® Simplant® Customer Service

Atlantis® Simplant® Customer service Australia France Norway Dentsply Sirona Implants DENTSPLY IH SAS DENTSPLY Implants 19/39 Herbert Street 7, rue Eugène et Armand Peugeot, TSA 90002 Karihaugveien 89, NO-1086 Oslo St Leonards NSW 2065 FR-92563 Rueil Malmaison Cedex Tel: +47 815 59 119 Tel: 1800 799 287 within Australia (freecall) Tel: +33 1 41 39 06 31 [email protected] 0800 408 349 from New Zealand (freecall) Fax: +33 1 41 39 82 09 Fax: 1800 799 187 within Australia [email protected] 0800 408 350 from New Zealand [email protected] Poland DENTSPLY IH Sp. z o.o. Germany ul. Wiertnicza 83, 02-952 Warszawa DENTSPLY IH GmbH Tel: +48 22 853 67 06 Austria Steinzeugstraße 50, DE-68229 Mannheim Fax:+48 22 853 67 10 Dentsply IH Gmbh / Austria & CEE Tel: +49 621 4302 013 [email protected] Liesinger Flur-Gasse 4 Fax: +49 621 4302 011 1230 Wien Tel: +49 621 4302 019 Design-Suprastrukturen Tel: +43 1 205 1200 5135 [email protected] Fax: +43 1 205 1200 5128 [email protected] Sweden DENTSPLY Implants Iberia P.O. Box 14, SE-431 21 Mölndal Dentsply Sirona Iberia SAU Tel: +46 31 376 30 20 Benelux Paseo de la Zona Franca, 111 – Planta 5 Fax: +46 31 376 30 17 DENTSPLY Implants Edificio Auditori – Porta Firal [email protected] Signaalrood 55, NL-2718 SG Zoetermeer 08038 Barcelona Tel: +31 79 360 19 55/+32 3 232 81 50 Tel: +34 93 263 78 20 Fax: +31 79 362 37 48/+32 3 213 30 66 Implants-BarcelonaESP-ATLANTISCustomerService@ [email protected] dentsplysirona.com Switzerland DENTSPLY IH SA Rue Galilée 6, CEI3, Y-Parc Canada CH - 1400 Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland Italy Tel: +41 21 620 02 30 DENTSPLY Implants Dentsply Italia Fax: +41 800 845 845 161 Vinyl Court P.zza dell’Indipendenza 11/B [email protected] Woodbridge, ON L4L 4A3 IT-00185 Roma (RM) Tel: 800-882-2022 Tel. -

Aladdin: the Movies 0.5 WIP +1000CP

Aladdin: The Movies 0.5 WIP Follow me to a place where incredible feats Are routine every hour or so Where enchantment runs rampant Gets wild in the streets Open sesame, here we go Arabian nights Like Arabian days They tease and excite Take off and take flight They shock and amaze Arabian nights Like Arabian days More often than not Are hotter than hot In a lot of good ways Pack your shield, pack your sword You won't ever get bored Though get beaten or gored you might Come on down, stop on by Hop a carpet and fly To another Arabian night Welcome to the Aladdin expanded universe. From a time when Disney wanted all of its movies to explain the lore behind the worlds. What, don’t believe me? Alright, they just wanted more money, but this place is still full of wonder. Anyway you are bound for the time period of Aladdin. It is a land of wonder that is rip to explore. Ancient ruins dot the landscape and mythical creatures roam. You start with the first movie. On the night that Gazeem is killed by the Cave of Wonders. Jafar has yet to trick Aladdin and set the plot in motion. If you are quick, you may be able to disturb the story. +1000CP Locations: Start in Agrabah or roll a 1d8 if you want more fun. 1. Agrabah, Arabia: Capital of city of one of the Seven Deserts. It is home to the street rat Aladdin and Princess Jasmine. This sprawling city is protected on three sides by hills and mountains. -

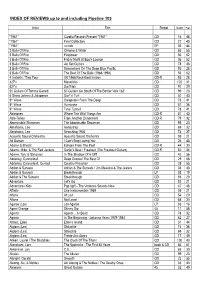

INDEX of REVIEWS up to and Including Pipeline 103

INDEX OF REVIEWS up to and including Pipeline 103 Artist Title Format Issue Page "1961" Carelia Records Present "1961" CD 16 48 "1961" Final Collection CD 27 43 "1961" no title EP 05 44 3 Balls Of Fire Chrome & Water CD 65 55 3 Balls Of Fire Firepower CD 56 52 3 Balls Of Fire Friday Night At Ego's Lounge CD 56 52 3 Balls Of Fire Jet Set Guitars CD 78 46 3 Balls Of Fire Somewhere On The Deep Blue Pacific CD 93 28 3 Balls Of Fire The Best Of The Balls (1988-1998) CD 56 52 4 Instants / Trax Four UK 1966 Rock-Beat Instros CD-R 93 28 427's Mavericks CD 102 31 427's Surf Noir CD 97 29 50 Guitars Of Tommy Garrett 50 Guitars Go South Of The Border Vols 1&2 CD 99 23 6 String Johnny & Jalapenos Surf 'n' Turf CD 40 43 9th Wave Creepsters From The Deep CD 78 41 9th Wave Hurricane CD 51 38 9th Wave Time Tunnel CD 78 41 Abletones Where The Wild Things Are CD-R 81 43 Able-Tones From Another Dimension! CD-R 79 32 Abominable Showmen The Abominable Showmen CD 95 23 Abrahams, Leo Honeytrap CD 69 32 Abrahams, Leo Searching 1906 CD 73 37 Acoustic Sound Orchestra Acoustic Sound Orchestra CD 59 21 Ad Damen I Can't Stop Loving You CD 26 45 Adams & Bryant Echoes From The Past CD-R 44 30 Adams, Mike, & The Red Jackets Surfer's Beat / Freakout (The Freakout Guitars) CD-R 82 34 Adams, Ton, & Stingrays In The Shadow Of A Cliff CD 42 56 Adderley, Cannonball Deep Groove! The Best Of CD 29 58 Adderley, Cannonball, Quintet Country Preacher CD 29 55 Adrian & Sunsets Adrian & The Sunsets / Jim Messina & The Jesters CD 33 43 Adrian & Sunsets Breakthrough LP 03 19 Adrian -

Appendix 1 Further Shadows Titles

APPENDIX 1 FURTHER SHADOWS TITLES The main body of this book is concerned with tracks issued between 1959 and 2004 and marketed through regular retail channels on vinyl and/ or compact disc. To provide a fuller picture of the range of music attempted by the group over the years, here is a list of other titles The Shadows are known to have performed on tour/ on stage, together with numbers from radio and TV. It includes vocal renditions of titles put out (whether before or after a given performance) as instrumentals. Indeed, nearly all of this ‘extra’ material is vocal, which by its very nature demands less precision and presumably significantly less in the way of rehearsal time, particularly for the lead guitarist, who can and usually does improvise in the solos assigned to him. Many of the items listed have been made available over the years on bootlegs of variable quality emanating chiefly from Holland, Italy, France and the UK. Sometimes, in an effort to play down the element of illegality, the dissemination of such material is represented as the (harmless, unselfish) activity of dedicated fans passing on privately taped music from one to another. Nonetheless, whether a given number is copied on to a cassette or a CD-R in a domestic setting, or finds its way into the hands of individuals or outfits with access to high-quality CD pressing plants, is in the last resort immaterial, especially as in the latter case, and certainly very commonly if not invariably in the former case too, money changes hands. -

But Our Extra Diligence Won't Be Effective Without

Here’s how you can help: 1) Please be transparent about where 3) Please practice (over and over...and always, we’re looking forward you have traveled recently: Within over again) good hygiene: Coughing to your joining us at the the past month, if you have visited or sneezing into your elbow (or a Atlantis—whether it’s for a destination deemed of concern tissue that you then flush or trash), the first or 100th time (or any time in by the CDC https://www.cdc.gov/ and always washing and sanitizing between.) And, as always, we will give coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/after- your hands whenever you can. 110% in trying to make the Atlantis a travel-precautions.html please follow restful, fun, and safe place for you to stay. their recommendations to stay at home 4) Please let us know if you are not at least 15 days upon your return. This feeling well: If you are here vacationing But COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) currently includes travel to and from: with us and feel unwell (fever of presents us with a unique challenge by ✺ China 100.4°F/38°C or higher, cough, or highlighting the fact that we know little ✺ Iran have trouble breathing), please CALL or nothing about our guests’ recent travels ✺ South Korea US as soon as you can, and we will or their current state of health. Given this ✺ Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, help you obtain medical assistance. uncertainty, how can we help ensure the Denmark, Estonia, Finland, health and safety of ALL of our guests? France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Thank you for joining us here at the We will continue to do our part by Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Atlantis, and for helping everyone keeping our hygiene standards high— Netherlands, Norway, Poland, stay healthy while you’re here. -

Atlantis: the Antideluvian World

Atlantis: The Antideluvian World Ignatius Donnelly Atlantis: The Antideluvian World Table of Contents Atlantis: The Antideluvian World....................................................................................................................1 Ignatius Donnelly.....................................................................................................................................1 PART I. THE HISTORY OF ATLANTIS...........................................................................................................2 CHAPTER I. THE PURPOSE OF THE BOOK.....................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. PLATO'S HISTORY OF ATLANTIS............................................................................3 CHAPTER III. THE PROBABILITIES OF PLATO'S STORY..........................................................11 CHAPTER IV. WAS SUCH A CATASTROPHE POSSIBLE?..........................................................16 CHAPTER. V. THE TESTIMONY OF THE SEA...............................................................................21 CHAPTER VI. THE TESTIMONY OF THE FLORA AND FAUNA................................................23 PART II. THE DELUGE....................................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER I. THE DESTRUCTION OF ATLANTIS DESCRIBED IN THE DELUGE LEGENDS.............................................................................................................................................27 -

The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies

$€ social sciences £ ¥ The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies Edited by Lauren Dundes Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Social Sciences www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies Special Issue Editor Lauren Dundes MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Lauren Dundes Department of Sociology, McDaniel College USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Social Sciences (ISSN 2076-0760) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ socsci/special issues/Disney Movies Psychosocial Implications) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-848-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-849-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Hsun-yuan Hsu. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies” .................. -

SHADOWS' UK Lps 1961–1972

SHADOWS’ UK LPs 1961–1972 Jim Nugent The Shadows LP (1961) [UK: Columbia 33SX 1374 (m) / SCX 3414 (s); September 1961] 2 SIDE ONE: 1. Shadoogie 2. Blue Star 3. Nivram 4. Baby My Heart (vocal with electric guitars) 5. See You In My Drums 6. All My Sorrows (folky vocal with acoustic guitars) 7. Stand Up And Say That! (piano-based instrumental; Hank on piano) SIDE TWO: 1. Gonzales 2. Find Me A Golden Street 3. Theme From A Filleted Place 4. That's My Desire (vocal with electric guitars) 5. My Resistance Is Low 6. Sleepwalk 7. Big Boy Shadoogie, Nivram, See You In My Drums, Stand Up And Say That!, Gonzales, Theme From A Filleted Place and Big Boy were group-composed originals. Let's not start arguing about the (earlier) South African compilation album "Rocking Guitars". For all practical purposes, it’s this one which is the Shadows' first long-player - and very probably their most fondly-remembered. The release is certainly the non-compilation disc from which they have performed the highest number of tracks live over the years, with Shadoogie and Nivram being staples of the stage act right up until 2005 and Shadoogie included in the Reunion tour(s) with Cliff Richard. Other numbers performed live at some time or other (whether by The Shadows or Hank Marvin as a solo act) include All My Sorrows , Sleepwalk , Stand Up And Say That and Gonzales . It would be remiss of me not to remark on that iconic uncredited cover-shot (by Dezo Hoffman?). Although the famous red, maple-necked Stratocaster is present, the body and "that colour" are hardly visible, perhaps deliberately hidden because it is, after all, a bit knocked about by this stage and just about to be replaced with a shiny new one.