Explaining Technical Breakdowns in Political Communication: Data, Analytics, and the 2012 Presidential Campaign Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republicans? Ethnicities, Economic and the First District in the Schools

Volume XVII, Number XXXIV September 11 - September 17, 2008 Masters of COVER STORY the Grill 1100 Summit Avenue, Suite 101 (@ Avenue K) • Plano, Texas 75074 Visit Us Online at www.NorthDallasGazette.com Palin's Speech o Slam Dunk, Black Women Say By. Eric Mayes of his or her race or gen- Party defeating a woman, PA der, insist they are simply to face another as his backing the best candi- opponent’s running mate. Sarah Palin’s speech last date. That slate of candidates week at the Republican Race and gender have made Black women one of National Convention been volatile issues in this the most discussed demo- evoked mixed reaction presidential election cycle, graphics of the campaign among Black women, which has seen a Black season. Polls show that the who, rather than backing man secure the nomina- vast majority intend to either candidate because tion of the Democratic See REPUBLICAS. Page 12 See RICKY RAYS, Page 9 Get your blues fix at the Blind RISD to Implement New Anti-Bullying Program Lemon Blues Festival this weekend For more information see pg. 10 From staff reports working cooperatively on has been used in England RTime seeks to teach www.northdallasgazette.com tasks, and expressing real since 2002 with impres- social behavior and skills A little common cour- gratitude to each other sive results. RTime was to students from tesy and social develop- along with other kind introduced at three pilot Kindergarten through 6th- What Has ment goes a long way for words. campuses in RISD during grade. The lessons elementary students in This is how a new anti- the first week of classes, learned are then reinforced Happened to the Richardson ISD. -

Bloomberg Politics GOP Unity Tracker

Bloomberg Politics GOP Unity Tracker Below is a list of who current Republican office-holders, mega-donors, and influential conservatives plan to support in November, as of Bloomberg's latest count on June 7, 2016. Name Unity Status Group State Gov. Robert Bentley Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Rep. Bradley Byrne Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Rep. Martha Roby Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Rep. Mike Rogers Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Rep. Robert Aderholt Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions Trump supporter Elected Officials Alabama Rep. Trent Franks Trump supporter Elected Officials Arizona Rep. Steve Womack Trump supporter Elected Officials Arkansas Rep. Darrell Issa Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Duncan Hunter Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Ken Calvert Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Kevin McCarthy Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Mimi Walters Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Paul Cook Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Tom McClintock Trump supporter Elected Officials California Rep. Doug Lamborn Trump supporter Elected Officials Colorado Rep. Scott Tipton Trump supporter Elected Officials Colorado Gov. Rick Scott Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. Curt Clawson Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. Dennis Ross Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. Jeff Miller Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. John Mica Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. Ted Yoho Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Rep. Vern Buchanan Trump supporter Elected Officials Florida Gov. Nathan Deal Trump supporter Elected Officials Georgia Rep. Austin Scott Trump supporter Elected Officials Georgia Rep. Doug Collins Trump supporter Elected Officials Georgia Rep. Lynn Westmoreland Trump supporter Elected Officials Georgia Rep. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

Using Design Strategy to Add Value to a Political Campaign a Thesis

Using Design Strategy to add Value to a Political Campaign A thesis submitted to the School of Visual Communication Design, College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts by Lee A. Zelenak auGusT, 2013 Thesis written by Lee A. Zelenak B.A./M.F.A., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Professor, Ken Visocky O’Grady, M.F.A., Advisor, School of Visual Communication Design AnnMarie LeBlanc, M.F.A., Director, School of Visual Communication Design Stanley T. Wearden, P.h.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents ACKNowlEDGMENTS ..........................................................................................................V PREfacE ....................................................................................................................................VI LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................VII CHAPTER I: Introduction ........................................................................................................1 Political Campaigns and Design ...................................................................................2 Design Strategy ...............................................................................................................3 Thesis Statement .............................................................................................................4 CHAPTER II: -

Mark Steyn, Fred Thompson, John Bolton, Victor Davis Hanson, & Many More Tremendous Speakers (Ok, We’Ll Name Them)

2011_08_01_cover61404-postal.qxd 7/12/2011 8:15 PM Page 1 August 1, 2011 49145 $4.99 MAGGIE GALLAGHER: WHAT’S NEXT FOR MARRIAGE? UnfairUnfair LaborLabor PracticesPractices The Case Against America’s Nightmarish Labor Law $4.99 31 Robert VerBruggen 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/12/2011 11:30 PM Page 1 toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 7/13/2011 1:28 PM Page 2 Contents AUGUST 1, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 14 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 31 National Labor Robert Costa on Thaddeus McCotter Relations Bias p. 21 The National Labor Relations Board under Obama has made BOOKS, ARTS few friends among conservatives. & MANNERS But the current behavior of the 40 HOW BIG HE IS David Paul Deavel reviews NLRB is only the outermost layer of G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, the true problem: the National Labor by Ian Ker. Relations Act. Robert VerBruggen 41 ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY? Victor Davis Hanson reviews The Wave: Man, God, and the Ballot COVER: UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD/CORBIS Box in the Middle East, by Reuel ARTICLES Marc Gerecht, and Trial of a Thousand Years: World Order 16 ROMNEY’S RESISTIBLE RISE by Ramesh Ponnuru and Islamism, by Charles Hill. The GOP contemplates a wedding of convenience. 43 THE NIEBUHRIAN MEAN 20 REAGAN’S LASTING REALIGNMENT by Michael G. Franc Daniel J. Mahoney reviews Why It shapes politics still. Niebuhr Now?, by John Patrick Diggins. 21 A HARD DAY’S NIGHT by Robert Costa Rep. Thaddeus McCotter wins the insomniac caucus. 45 CHINA’S BIG LIE John Derbyshire reviews Such Is 23 GAY OLD PARTY? by Maggie Gallagher This [email protected], How New York Republicans caved, and where the marriage campaigns go next. -

Broadway Premiere of "8" Lifts Veil on Prop

Broadway Premiere of "8" Lifts Veil on Prop. 8 Trial NEW YORK, July 18, 2011 /PRNewswire/ -- Today the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER) and Broadway Impact announced the Broadway premiere of "8", a play chronicling the historic trial in the federal legal challenge to California's Proposition 8, written by AFER Founding Board Member and Academy-Award winning writer Dustin Lance Black and directed by Tony Award-winning actor and director Joe Mantello. The production is an unprecedented account of the Federal District Court trial of Perry v. Schwarzenegger, the case filed by AFER to overturn Prop. 8, which eliminated the right to marry for gay and lesbian couples in California. Black, who penned the Academy-Award winning feature film "Milk," based "8" on the actual words of the trial transcripts, first-hand observations of the courtroom drama and interviews with the plaintiffs and their families. It is set to premiere at the Eugene O'Neill Theatre in New York City on Monday, September 19, 2011 for an exclusive, one night only fundraiser to benefit AFER. High profile and award-winning actors will play the roles of the legal team, plaintiffs and witnesses for both sides of the historic Prop. 8 case. Casting for the all-star benefit will be announced soon. Following the New York debut on September 19, AFER and Broadway Impact will license "8" to schools and community organizations nationwide in order to spur action, dialogue and understanding. AFER and Broadway Impact will help produce these staged readings across the country, so that "8"will live on beyond its September premiere. -

Sheldon Adelson's Spider

Summer 2014 The Social Contract Sheldon Adelson’s Spider Web Where special interests intersect with immigration BY PETER GEMMA heldon Adelson is the 10th richest person in the and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. world — some say the eighth, but why quibble Perusing the Internet finds several more recent invest- Sabout a few billion dollars. Undoubtedly, he’s ments: $180 million for a youth exchange program, among the one percent of the one percent of Ameri- $67 million to a medical research center, $50 million ca’s political elites. The Center for Responsive Politics to expand an education campus, and a $16 million gift reports that during the 2012 elections, Adelson gave given towards Israel’s attempt to land a spacecraft on $20 million to Winning Our Future, the super PAC that the moon. promoted Newt Gingrich’s presidential bid, then poured When it comes to cornering and protecting the $30 million into the Restore Our Future, one of the gambling market, Adelson has no peer: he made more super PACs supporting former Massachusetts Governor money in the last three years than any other American. Mitt Romney. He also underwrote GOP operative Karl His Las Vegas Sands Corporation is the largest casino Rove’s political operation to the tune of $23 million. All company in the world, with annual revenues of more told, Adelson and his wife invested $100 million in the than $11 billion — it’s been estimated that his world- 2012 campaign sweepstakes, more money for one elec- wide gaming interests earn him $1 million an hour. -

106Th Congress 255

TEXAS 106th Congress 255 TEXAS (Population 1998, 19,760,000) SENATORS PHIL GRAMM, Republican, of College Station, TX; born in Fort Benning, GA, July 8, 1942, son of Sergeant and Mrs. Kenneth M. Gramm; B.B.A. and Ph.D., economics, University of Georgia, Athens, 1961±67; professor of economics, Texas A&M University, College Station, 1967±78; author of several books including: ``The Evolution of Modern Demand Theory'' and ``The Economics of Mineral Extraction''; Episcopalian; married Dr. Wendy Lee Gramm, of Waialua, HI, 1970; two sons: Marshall and Jeff; coauthor of the Gramm-Latta I Budget, the Gramm-Latta II Omnibus Reconciliation Act and the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings balanced budget bill; committees: Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry; chairman, Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1978, 1980 and 1982; resigned from the House on January 5, 1983, upon being denied a seat on the House Budget Committee; reelected as a Republican in a special election on February 12, 1983; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 6, 1984; reelected in 1990 and 1996; elected chairman, U.S. Senate Steering Committee, 1997±98; elected chairman, National Republican Senatorial Committee for the 1991±92 term, and reelected for the 1993±94 term. Office Listings http://www.senate.gov/senator/gramm.html 370 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510±4302 .......................... (202) 224±2934 Chief of Staff.ÐRuth Cymber. Legislative Director.ÐRichard Ribbentrop. Press Secretary.ÐLawrence A. Neal. State Director.ÐPhil Wilson. Suite 1500, 2323 Bryan, Dallas, TX 75201 ................................................................. (214) 767±3000 222 East Van Buren, Harlingen, TX 78550 ................................................................ -

Ken Mehlman, David Kochel, and Iowa Conservatives Speak out In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Release January 28, 2013 Ken Mehlman, David Kochel, and Iowa Conservatives Speak Out in Support of Marriage Equality ‘The freedom to marry is consistent with conservative principles,’ say advocates (Des Moines, IA)—Today, Iowa conservatives joined Ken Mehlman—a New York businessman, former Republican National Committee Chairman, and the architect of President Bush’s 2004 successful campaign—for a public event in Des Moines to discuss support for marriage for same-sex couples, and the future of the Republican Party. The public event was held at Davis Brown Law Firm and hosted by Iowa Republicans for Freedom (IRFF), the public education organization making the conservative case for marriage. “Allowing civil marriage for all Americans promotes freedom, cultivates family values like community stability, fidelity and commitment and follows the Golden Rule,” said Mehlman. “Like Dick Cheney, Clint Eastwood, John Bolton and Ted Olson, these Iowa conservatives support civil marriage because of our principles, not in spite of our philosophy.” The event drew more than 30 Iowa conservatives from around the state. Attendees and participants were encouraged to talk to other Iowa conservatives—family, friends and church members—about supporting marriage for same-sex couples. Mehlman was joined by David Kochel, Mitt Romney’s Iowa strategist and founder of Red Wave Communications, who expressed his support for marriage at the event and his desire to see the Iowa Republican Party support civil marriage for same-sex couples. “Support for the freedom to marry is emerging as a mainstream position in the Republican Party. If we are to be the party of principles and values, isn’t our first obligation to the principle of freedom, and the value of individual liberty?” said Kochel. -

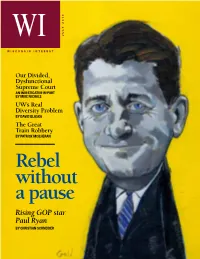

Rebel Without a Pause Rising GOP Star Paul Ryan by Christian Schneider Editor > Charles J

WI 2010 JULY WISCONSIN INTEREST Our Divided, Dysfunctional Supreme Court AN INVESTIGATIVE REPORT BY MIKE NICHOLS UW’s Real Diversity Problem BY DAVID BLASKA The Great Train Robbery BY PATRICK MCILHERAN Rebel without a pause Rising GOP star Paul Ryan BY CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER Editor > CHARLES J. SYKES Hard choices WI WISCONSIN INTEREST For a rising political star, Paul Ryan remains a nation’s foremost celebrity wonk, asking: remarkably lonely political figure. For years, “What’s so damn special about Paul Ryan?” under both Democrats and Republicans, he More than his matinee-idol looks. has warned about the need to avert a fiscal “Ryan is a throwback,” writes Schneider, Publisher: meltdown, but even though his detailed “he could easily have been a conservative Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, Inc. “Roadmap” for restraining government politician in the era before cable news. He spending was widely praised, it was embraced has risen to national stardom by taking the Editor: Charles J. Sykes by very few. path least traveled by modern politicians: He Despite lip-service praise from President knows a lot of stuff.” Managing Editor: Marc Eisen Obama, Democrats have launched serial Also in this issue, Mike Nichols examines Art Direction: attacks against the plan, while GOP leaders Wisconsin’s dysfunctional, divided Supreme Stephan & Brady, Inc. have made themselves scarce, avoiding being Court and the implications for law in the state. Contributors: yoked to the specificity of Ryan’s hard choices. Patrick McIlheran deconstructs the state’s David Blaska But Ryan’s warnings have taken on new signature boondoggle, the billion-dollar not- Richard Esenberg urgency as Europe’s debt crisis unfolds, and so-fast train from Milwaukee to somewhere Patrick McIlheran the U.S. -

RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict Fo

RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/13/AR... Hello mbowen Change Preferences | Sign Out Print Edition | Subscribe SEARCH: News | Search Archives washingtonpost.com > Politics Print This Article RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit E-Mail This Racial Conflict for Votes Article By Mike Allen Thursday, July 14, 2005; Page A04 It was called "the southern strategy," started under Richard M. Nixon in 1968, and described Republican efforts to use race as a wedge issue -- on matters such as desegregation and busing -- to appeal to white southern voters. Ken Mehlman, the Republican National Committee chairman, this morning will tell the NAACP national convention in Milwaukee that it was "wrong." "By the '70s and into the '80s POLITICS TRIVIA and '90s, the Democratic Party solidified its gains in the Which U.S. president had the African American community, largest feet? and we Republicans did not effectively reach out," Mehlman Warren G. Harding says in his prepared text. "Some Abraham Lincoln Republicans gave up on James Monroe winning the African American Bill Clinton vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from Check Your Answer racial polarization. I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong." Mehlman, a Baltimore native who managed President Bush's reelection campaign, goes on to discuss current overtures to minorities, calling it "not healthy for the country for our political parties to be so racially polarized." The party lists century-old outreach efforts in a new feature on its Web site, GOP.com, which was relaunched yesterday with new interactive features and a history section called "Lincoln's Legacy." Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean spoke to the NAACP yesterday and said through an aide: "It's no coincidence that 43 out of 43 members of the Congressional Black Caucus are Democrats. -

How a Race in the Balance Went to Obama

How a Race in the Balance Went to Obama Doug Mills/The New York Times President Obama, with his family, returned to the White House on Wednesday, after a bruising re-election fight with many twists and turns. By ADAM NAGOURNEY, ASHLEY PARKER, JIM RUTENBERG and JEFF ZELENY Published: The New York Times National Edition, November 7, 2012, P1, P14 Seven minutes into the first presidential debate, the mood turned from tense to grim inside the room at the University of Denver where Obama staff members were following the encounter. Top aides monitoring focus groups — voters who registered their minute-by- minute reactions with the turn of a dial — watched as enthusiasm forMitt Romney spiked. “We are getting bombed on Twitter,” announced Stephanie Cutter, a deputy campaign manager, while tracking the early postings by political analysts and journalists whom the Obama campaign viewed as critical in setting debate perceptions. By the time President Obama had waded through a convoluted answer about health care — “He’s not mentioning voucher-care?” someone called out — a pall had fallen over the room. When the president closed by declaring, “This was a terrific debate,” his re-election team grimaced. There was the obligatory huddle to discuss how to explain his performance to the nation, and then a moment of paralysis: No one wanted to go to the spin room and speak with reporters. Mr. Romney’s advisers monitored the debate up the hall from the Obama team, as well as at campaign headquarters in Boston. Giddy smiles flashed across their faces as their focus groups showed the same results.