Liberty, Justice, and the Rule of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hume's Theory of Justice*

RMM Vol. 5, 2014, 47–63 Special Topic: Can the Social Contract Be Signed by an Invisible Hand? http://www.rmm-journal.de/ Horacio Spector Hume’s Theory of Justice* Abstract: Hume developed an original and revolutionary theoretical paradigm for explaining the spontaneous emergence of the classic conventions of justice—stable possession, trans- ference of property by consent, and the obligation to fulfill promises. In a scenario of scarce external resources, Hume’s central idea is that the development of the rules of jus- tice responds to a sense of common interest that progressively tames the destructiveness of natural self-love and expands the action of natural moral sentiments. By handling conceptual tools that anticipated game theory for centuries, Hume was able to break with rationalism, the natural law school, and Hobbes’s contractarianism. Unlike natu- ral moral sentiments, the sense of justice is valuable and reaches full strength within a general plan or system of actions. However, unlike game theory, Hume does not assume that people have transparent access to the their own motivations and the inner structure of the social world. In contrast, he blends ideas such as cognitive delusion, learning by experience and coordination to construct a theory that still deserves careful discussion, even though it resists classification under contemporary headings. Keywords: Hume, justice, property, fictionalism, convention, contractarianism. 1. Introduction In the Treatise (Hume 1978; in the following cited as T followed by page num- bers) and the Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (Hume 1983; cited as E followed by page numbers)1 Hume discusses the morality of justice by using a revolutionary method that displays the foundation of justice in social utility and the progression of mankind. -

The Relationship Between Capitalism and Democracy

The Relationship Between Capitalism And Democracy Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Petkovic, Aleksandra Evelyn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 12:57:19 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625122 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CAPITALISM AND DEMOCRACY By ALEKSANDRA EVELYN PETKOVIC ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and Law THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA M A Y 2 0 1 7 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Thomas Christiano Department of Philosophy Abstract This paper examines the very complex relationship between capitalism and democracy. While it appears that capitalism provides some necessary element for a democracy, a problem of political inequality and a possible violation of liberty can be observed in many democratic countries. I argue that this political inequality and threat to liberty are fueled by capitalism. I will analyze the ways in which capitalism works against democratic aims. This is done through first illustrating what my accepted conception of democracy is. I then continue to depict how the various problems with capitalism that I describe violate this conception of democracy. This leads me to my conclusion that while capitalism is necessary for a democracy to reach a certain needed level of independence from the state, capitalism simultaneously limits a democracy from reaching its full potential. -

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

National Honor Society Liberty High School Chapter LHS Chapter of The

National Honor Society Liberty High School Chapter 1115 Linden Street Bethlehem, PA 18018 LHS Chapter of the National Honor Society A pplication Criteria and Requirements Criteria to Receive an Application: Students must have a 3.75 cumulative GPA at the end of their Sophomore or Junior year to receive an application at the beginning of their Junior or Senior year, respectively. How to Apply: Students will receive an application packet at the beginning of the school year in which they are eligible (Junior or Senior year). The application must be completely filled out and returned on the due date in September. The sections are as follows: Section I - Community Service Juniors applying must have at least 30 hours of community service completed (ie: 15 hours/year). Seniors applying must have at least 45 hours completed It is recommended that students complete all 60 hours of community service prior to applying at a minimum Section II - Essay Statement Demonstrate how you plan to incorporate the four pillars of the National Honor Society into your future experiences and endeavors: F our Pillars: I. Scholarship II: Leadership III: Service IV: Character Section III - Leadership Positions List any/all leadership positions you feel may be appropriate. The more positions listed, the better Section IV - Structured Extracurricular Activities/Work List any/all activities you feel are relevant. The more activities listed, the better. Section V - Teacher Recommendations Requirements Once Accepted: Attendance ALL meetings are mandatory unless otherwise noted. If you fail to come to a meeting without an excuse, you will have a meeting with Mr. -

5. What Matters Is the Motive / Immanuel Kant

This excerpt is from Michael J. Sandel, Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do?, pp. 103-116, by permission of the publisher. 5. WHAT MATTERS IS THE MOTIVE / IMMANUEL KANT If you believe in universal human rights, you are probably not a utili- tarian. If all human beings are worthy of respect, regardless of who they are or where they live, then it’s wrong to treat them as mere in- struments of the collective happiness. (Recall the story of the mal- nourished child languishing in the cellar for the sake of the “city of happiness.”) You might defend human rights on the grounds that respecting them will maximize utility in the long run. In that case, however, your reason for respecting rights is not to respect the person who holds them but to make things better for everyone. It is one thing to con- demn the scenario of the su! ering child because it reduces overall util- ity, and something else to condemn it as an intrinsic moral wrong, an injustice to the child. If rights don’t rest on utility, what is their moral basis? Libertarians o! er a possible answer: Persons should not be used merely as means to the welfare of others, because doing so violates the fundamental right of self-ownership. My life, labor, and person belong to me and me alone. They are not at the disposal of the society as a whole. As we have seen, however, the idea of self-ownership, consistently applied, has implications that only an ardent libertarian can love—an unfettered market without a safety net for those who fall behind; a 104 JUSTICE minimal state that rules out most mea sures to ease inequality and pro- mote the common good; and a celebration of consent so complete that it permits self-in" icted a! ronts to human dignity such as consensual cannibalism or selling oneself into slav ery. -

United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory

Michigan Journal of Gender & Law Volume 8 Issue 1 2001 United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory R. Christopher Preston Brigham Young University Ronald Z. Ahrens Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl Part of the International Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation R. C. Preston & Ronald Z. Ahrens, United Nations Convention Documents in Light of Feminist Theory, 8 MICH. J. GENDER & L. 1 (2001). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl/vol8/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Gender & Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION DOCUMENTS IN LIGHT OF FEMINIST THEORY P, Christopher Preston* RenaldZ . hrens-* INTRODUCTION • 2 I. PROMINENT FEMINIST THEORIES AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW • 7 A Liberal/EqualityFeminism 7 B. CulturalFeminism . 8 C. DominanceFeminism • 9 1. Reproductive Capacity • 11 2. Violence . 12 3. Traditional Male Domination of Society • 12 II. WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTS • 13 A. United Nations Charter • 14 B. UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights • 15 C. The Two InternationalCovenants • 15 1. International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights • 16 2. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights • 16 D. Convention on the Elimination ofAll Forms of DiscriminationAgainst Women • 17 E. The NairobiForward Looking Strategies • 18 F. -

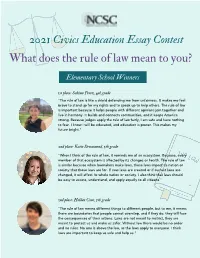

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Birth & Reconstruction of Equality in the United States Nascimento E

BIRTH & RECONSTRUCTION OF EQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES NASCIMENTO E RECONSTRUÇÃO DA IGUALDADE NOS ESTADOS UNIDOS Alexander Tsesis Loyola University School of Law (Chicago, IL, USA) Recebimento: 13 jan. 2020 Aceitação: 26 jan. 2020 Como citar este artigo / How to cite this article (informe a data atual de acesso / inform the current date of access): TSESIS, Alexander. Birth & reconstruction of equality in the United States. Revista da Faculdade de Direito UFPR, Curitiba, PR, Brasil, v. 64, n. 3, p. 75-106 set./dez. 2019. ISSN 2236-7284. Disponível em: <https://revistas.ufpr.br/direito/article/view/72128>. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/rfdufpr.v64i3.72128. ABSTRACT The United States was born of a normative and political aspiration asserted in its declaration of independence. The document did not simply contain a list of reasons for ending colonialization, but established equality as key ideal which remained imbedded in the nation’s ethos and is central for the U.S. representative democracy. Despite the normative statements of human rights, the status of the United States was deeply tainted because the framers of the Constitution retained protections for the institution of slavery. But many other legal and cultural anomalies also existed from the inception of nationhood, including the subjugation of women and the retention of propertied privileges as qualifications for voting and obtaining political offices. Amendments that were made to the Constitution after the Civil War (1861-1865) significantly advanced the rule of law but simultaneously required greater sincerity in abiding to the founding testament. Reconstruction in the United States was achieved through amendment of the original Constitution rather than the enactment of a new document. -

The Infirmity of Social Democracy in Postcommunist Poland a Cultural History of the Socialist Discourse, 1970-1991

The Infirmity of Social Democracy in Postcommunist Poland A cultural history of the socialist discourse, 1970-1991 by Jan Kubik Assistant Professor of Political Science, Rutgers University American Society of Learned Societies Fellow, 1990-91 Program on Central and Eastem Europe Working Paper Series #20 January 1992 2 The relative weakness of social democracy in postcommunist Eastern Europe and the poor showing of social democratic parties in the 1990-91 Polish and Hungarian elections are intriguing phenom ena. In countries where economic reforms have resulted in increasing poverty, job loss, and nagging insecurity, it could be expected that social democrats would have a considerable follOwing. Also, the presence of relatively large working class populations and a tradition of left-inclined intellec tual opposition movements would suggest that the social democratic option should be popular. Yet, in the March-April 1990 Hungarian parliamentary elections, "the political forces ready to use the 'socialist' or the 'social democratic' label in the elections received less than 16 percent of the popular vote, although the class-analytic approach predicted that at least 20-30 percent of the working population ... could have voted for them" (Szelenyi and Szelenyi 1992:120). Simi larly, in the October 1991 Polish parliamentary elections, the Democratic Left Alliance (an elec toral coalition of reformed communists) received almost 12% of the vote. Social democratic parties (explicitly using this label) that emerged from Solidarity won less than 3% of the popular vote. The Szelenyis concluded in their study of social democracy in postcommunist Hungary that, "the major opposition parties all posited themselves on the political Right (in the Western sense of the term), but public opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of social democratic measures" (1992:125). -

Equal Right of Men and Women to the Enjoyment of the Rights Set Forth in the Covenant

CCPR General Comment No. 18: Non-discrimination Adopted at the Thirty-seventh Session of the Human Rights Committee, on 10 November 1989 1. Non-discrimination, together with equality before the law and equal protection of the law without any discrimination, constitute a basic and general principle relating to the protection of human rights. Thus, article 2, paragraph 1, of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights obligates each State party to respect and ensure to all persons within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the Covenant without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Article 26 not only entitles all persons to equality before the law as well as equal protection of the law but also prohibits any discrimination under the law and guarantees to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. 2. Indeed, the principle of non-discrimination is so basic that article 3 obligates each State party to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of the rights set forth in the Covenant. While article 4, paragraph 1, allows States parties to take measures derogating from certain obligations under the Covenant in time of public emergency, the same article requires, inter alia, that those measures should not involve discrimination solely on the ground of race, colour, sex, language, religion or social origin.