1 Bealer Preliminary Pages PQ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

RESIDENTIAL CONTRACTOR GUIDELINES Rev

RESIDENTIAL CONTRACTOR GUIDELINES Rev. 09/2017 BUILDING INSPECTIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Code Compliance 2 General Information 3 Inspection Requests / Inspection Cancellations 4 Location of Permit Packet 4 Inspector Office Hours 5 Reinspection Fees 5 Inclement Weather 6 Inspection Requirements 7 T-Pole 7 Plumbing Rough 7 Foundation 8 Flatwork/Approach 9 Sheathing/Nail Pattern 10 Seconds 10 Framing 10 Electrical Rough 12 Plumbing Top-Out 12 Mechanical Rough 13 Fireplace 14 Gas Pressure Test 14 Four (4) Foot Brick 15 Insulation 15 Drywall 15 Gas & Electric Release (Utility Release – Permanent Service) 15 Gas Release 16 Electric Release 16 Temporary Heat 17 Public Works 17 Building Final (Certificate of Occupancy) 18 Plumbing Final 19 Electrical Final 19 Mechanical Final 20 Fence Final 21 Irrigation (DCA/Backflow) Final 21 Energy Final 21 Building Final 21 Summary 22 Attachments Builders Designated Subdivision Wash-Out Pit 23 Building Lot Erosion & Debris Containment Plan 24 Residential Drive Approach Detail 25 Barrier Free Ramp at Intersection 26 Residential Contractor Guidelines – Rev. 9/17 Page 1 of 26 Physical Address: 409 E First Street / Mailing Address: PO Box 307, Prosper, TX 75078 Office: 972-346-3502 / Fax: 972-347-2842 / Email: [email protected] Code Compliance Construction projects must adhere to the following codes: 2012 International Energy Conservation Code, Ord. #14-47, effective, October 1, 2014 Effective September 1, 2016, State of Texas adopted Phase 1 of the 2015 IECC. 2011 National Electrical Code, Ord. #14-50, effective, October 1, 2014 2012 International Residential Code, Ord. #14-45, effective, October 1, 2014 2012 International Mechanical Code, Ord. -

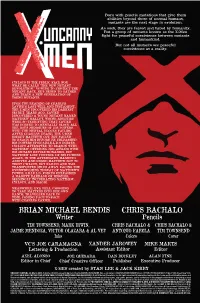

Brian Michael Bendis Chris Bachalo

Born with genetic mutations that give them abilities beyond those of normal humans, mutants are the next stage in evolution. As such, they are feared and hated by humanity. But a group of mutants known as the X-Men fight for peaceful coexistence between mutants and humankind. But not all mutants see peaceful coexistence as a reality. CYCLOPS IS THE PUBLIC FACE FOR WHAT HE CALLS “THE NEW MuTANT REVOLuTION.” VOWING TO PROTECT THE MuTANT RACE, HE’S BEGuN TO GATHER AND TRAIN A NEW GENERATION OF YOUNG MUTANTS. UPON THE READING OF CHARLES XAVIER’S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT, THE X-MEN UNCOVERED HIS DARKEST SECRET. YEARS AGO, XAVIER DISCOVERED A YOUNG MUTANT NAMED MATTHEW MALLOY, WHOSE ABILITIES WERE SO TERRIFYING THAT XAVIER WAS FORCED TO MENTALLY BLOCK ALL THE BOY’S MEMORIES OF HIS POWERS. WITH THE MENTAL BLOCKS FAILING AFTER CHARLES’ DEATH, THE x-MEN SOUGHT MATTHEW OUT, BUT FAILED TO REACH HIM BEFORE HE UNLEASHED HIS POWERS uPON S.H.I.E.L.D.’S FORCES. CYCLOPS ATTEMPTED TO REASON WITH MATTHEW, OFFERING HIM ASYLUM WITH HIS MUTANT REVOLUTIONARIES, BUT MATTHEW LOST CONTROL OF HIS POWERS AGAIN. IN THE AFTERMATH, MAGNETO ARRIVED AND URGED MATTHEW NOT TO TRUST CYCLOPS, BUT FAILED AND WAS TRANSPORTED MILES AWAY. FACING THE OVERWHELMING THREAT OF MATTHEW’S POWER, S.H.I.E.L.D. FORCES UNLEASHED A MASSIVE BARRAGE OF MISSILES, SEEMINGLY INCINERATING MATTHEW, CYCLOPS, AND MAGIK. MEANWHILE, EVA BELL, CHOOSING TO TAKE MATTERS INTO HER OWN HANDS, TRAVELLED BACK IN TIME, COMING FACE-TO-FACE WITH CHARLES XAVIER. BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS CHRIS BACHALO Writer Pencils TIM TOWNSEND, MARK IRWIN, CHRIS BACHALO & CHRIS BACHALO & JAIME MENDOZA, VICTOR OLAZABA & AL VEY ANTONIO FABELA TIM TOWNSEND Inks Colors Cover VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA XANDER JAROWEY MIKE MARTS Lettering & Production Assistant Editor Editor AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE Editor in Chief Chief Creative Officer Publisher Executive Producer X-MEN created by STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY X-MEN No. -

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality Dana Christine Volk Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In ASPECT: Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Approved: David L. Brunsma, Committee Chair Paula M. Seniors Katrina M. Powell Disapproved: Gena E. Chandler-Smith May 17, 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: passing, sexuality, gender, class, performativity, intersectionality Copyright 2017 Dana C. Volk Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class, and Sexuality Dana C. Volk Abstract for scholarly and general audiences African American Literature engaged many social and racial issues that mainstream white America marginalized during the pre-civil, and post civil rights era through the use of rhetoric, setting, plot, narrative, and characterization. The use of passing fostered an outlet for many light- skinned men and women for inclusion. This trope also allowed for a closer investigation of the racial division in the United States. These issues included questions of the color line, or more specifically, how light-skinned men and women passed as white to obtain elevated economic and social status. Secondary issues in these earlier passing novels included gender and sexuality, raising questions as to whether these too existed as fixed identities in society. As such, the phenomenon of passing illustrates not just issues associated with the color line, but also social, economic, and gender structure within society. Human beings exist in a matrix, and as such, passing is not plausible if viewed solely as a process occurring within only one of these social constructs, but, rather, insists upon a viewpoint of an intersectional construct of social fluidity itself. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

{PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50'S Horror and SF Comics by Alex Toth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50's Horror and S.F. Comics by Alex Toth Dick Briefer's Frankenstein: The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics HC (2010 IDW) comic books. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 1st printing. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. Frankenstein! Dick Briefer is one of the seminal artists who worked with Will Eisner on some of the very first comic books. If you like the comic-book weirdness of cartoonists Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, and Boody Rogers, you're sure to thrill over Dick Briefer's creation of Frankenstein. The large-format book lovingly reproduces a monstrous number of stories from the original 1940s and '50s comic books. The stories are fascinatingly supplemented by an insightful introduction with rare photos of the artist, original art, letters from Dick Briefer, drawings by Alex Toth inspired by Briefer's Frankenstein-and much more! Hardcover, 112 pages, full color. Cover price $21.99. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 2nd or later printings. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. -

Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicholas A. Brown for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on April 30, 2015 Title: Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies. Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________________________ Tim T. Jensen Ehren H. Pflugfelder This thesis complicates the traditional associations between authorship and alphabetic composition within the comics medium and examines how the contributions of line artists and writers differ and may alter an audience's perceptions of the medium. As a fundamentally multimodal and collaborative work, the popular superhero comic muddies authorial claims and requires further investigations should we desire to describe authorship more accurately and equitably. How might our recognition of the visual author alter our understandings of the author construct within, and beyond, comics? In this pursuit, I argue that the terminology available to us determines how deeply we may understand a topic and examine instances in which scholars have attempted to develop on a discipline's body of terminology by borrowing from another. Although helpful at first, these efforts produce limited success, and discipline-specific terms become more necessary. To this end, I present the visual/alphabetic author distinction to recognize the possibility of authorial intent through the visual mode. This split explicitly recognizes the possibility of multimodal and collaborative authorships and forces us to re-examine our beliefs about authorship more generally. Examining the editors' note, an instance of visual plagiarism, and the MLA citation for graphic narratives, I argue for recognition of alternative authorships in comics and forecast how our understandings may change based on the visual/alphabetic split. -

Garfield Minus Garfield

[Online library] Garfield Minus Garfield Garfield Minus Garfield Jim Davis *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks #369139 in Books Ballantine BooksModel: FBA-|282944 2008-10-28 2008-10-28Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 5.30 x .40 x 8.30l, .42 #File Name: 0345513878128 pages | File size: 64.Mb Jim Davis : Garfield Minus Garfield before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Garfield Minus Garfield: 9 of 9 people found the following review helpful. Very clever, indeed...By NecrJoeSome of the strips in this book are worth a half-smile...but others are worth a full-on out-loud laugh. It did make me notice, though, how many of the original "Garfield" strips were already all about Jon. For instance, some of the strips only remove Garfield's reaction after Jon has done something absolutely nutso. But don't let that take anything away from the heart of this book. There is some hilarious stuff there.Another interesting thing was the forward by the "editor" of the Garfield comics, and how he received fan mail from people who suffered from things like depression and other mental issues, and how they identified with Jon. I initially read through the book without having read the forward, but then after reading said forward...I read the book again, and from an entirely different set of eyes and enjoyed it on a whole 'nother dimension.You do really have to feel sorry for Jon by the end of the book, though. That guy's so sad.