Delhi Airport Metro Express

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report

Environmental Impact Assessment Study for Najafgarh- Dhansa Bus Stand Corridor of Delhi Metro FINAL REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR NAJAFGARH- DHANSA BUS STAND EXTENSION OF DELHI METRO March 2018 DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION Centre for Environment Research Metro Bhawan, Fire Brigade Lane, and Development LGCS-27A, Ansal Plaza, Vaishali, Ghaziabad- Barakhamba Road, New Delhi-110001 201010, U.P. Email:[email protected] 0 Environmental Impact Assessment Study for Najafgarh- Dhansa Bus Stand Corridor of Delhi Metro CONTENTS No. Description Page No. ABBREVIATIONS 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 1.1 INTRODUCTION 18 1.2 Legal, Policy And Institutional Frame Work 18 1.3 Enviromental Categorization and Clearances 19 1.4 Objective and Scope of the Study 21 1.5 Approach And Methodology 21 1.5.1 Data Collection 22 1.5.2 Environmental Impact Assessment 22 1.5.3 Environmental Management Plan 23 1.5.4 Environmental Monitoring 23 1.6 Format of the Report 23 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 25 2.0 Transport Situation in Delhi 25 2.1 Project Area 25 2.2 Proposed Metro Corridor 25 2.3 Location of Station 25 2.4 Traffic Projections 27 2.5 System Requirement 27 2.6 Rolling Stock Requirement 27 2.7 Construction Methodology 27 2.8 Maintenance Depot 27 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE DATA 28 3.1 Environmental Scoping 28 3.2 Land Environment 30 3.2.1 Geography, Geology And Soils 30 3.2.2 Seismicity 30 3.2.3 Soil Quality 31 3.3 Water Environment 32 1 Environmental Impact Assessment Study for Najafgarh- Dhansa Bus Stand Corridor of Delhi Metro 3.3.1 Water Resources 32 -

Nawada Metro Station Site Proposal

DESIGN STRECH-1.3 KM ALL CONNECTING MAJOR ROADS ARE REDEVELOPED TILL 500 M 6 2-wheeler & 4- wheeler Parking 7 IPT pick-drop Bay 9 No.s 2M Wide Footpath STAY PALM OYO DHINDRA HONDA DHINDRA 8 2M Wide 31 MUZ DUSTBIN BOX 32 DUSTBIN BOX Proposed Relocated Toilet Footpath 9 PALACE DUSTBIN BOX MUZ BUILT UP AREA GAHLOT ANKIT 10 SHIVAJI MARG -NAJAFGARH ROAD DUSTBIN BOX 11 IPT pick-drop Bay 8 No.s DUSTBIN BOX DUSTBIN BOX BUILT UP AREA DUSTBIN BOX 12 1500mm High Railing BANK ALLAHABAD DUSTBIN BOX BUILT UP AREA DUSTBIN BOX Traffic DUSTBIN BOX 14 BALAJI DUSTBIN BOX Calming Zone CORNER FOOD 13 Car/Cab/Uber pick-drop BUILT UP AREA DUSTBIN BOX S1 AGGARWAL PROPERTIES AGGARWAL BUILT UP AREA DUSTBIN BOX Bay 4 No.s S1 SIT HOLIDAY PRIVATE LIMITED 2M Wide Footpath Zebra Crossing TYRES MRF S7 15 DUSTBIN BOX MUZ 34 33 <<<SHIVAJI MARG -NAJAFGARH ROAD>>> S1 DUSTBIN BOX ENTERPRISES JAI SHRI RAM RAM SHRI JAI BUILT UP AREA S1 G ROOM BOX DUSTBIN MUZ S7 1 BOX DUSTBIN LIFT LAVANYA BANQUET HALL BANQUET LAVANYA DUSTBIN BOX MUZ NO2 GATE S9 29 DUSTBIN BOX DUSTBIN BOX S9 2M Wide S3 GPS AR AR Zebra Crossing AR 2M Wide Footpath AR 30 AR HOSPITAL MAHINDRU S3 AR NAWADA METRO STN BUILDING AR Footpath Bus Stop-1 5 S4 AR 2 DUSTBIN BOX ER ER SHRI SAI NATH MEDICAL NATH SAI SHRI ER GATE NO 1 NO GATE ER S5 EA EA S4 ER EA (proposed) DUSTBIN BOX 4 ER DUSTBIN BOX EXISTING TEMPORARY MOTORS DEWAN S5 TOILET RELOCATED S9 DUSTBIN BOX S8 S9 1500mm High PROPOSED RELOCATED TOILET DUSTBIN BOX AR S9 AR DUSTBIN BOX AR 3 AR BUILT UP AREA BUILT UP AREA BUILT UP AREA UP BUILT UP AREA BANK OF INDIA -

Infrastructure / Delhi Metro Changes Indian Lifestyles

Human Security and Quality Growth A women-only car on the Delhi Metro. The scene of passengers lining up for the train is just like that of Japan. It has become easier for women to A barrier-free design is also promoted at stations. work in the city because they can now commute with peace of mind. Women also play active roles in Delhi Metro operations The lifestyles of citizens have The implementation of safety measures at construction sites spread steadily as pro- jects were carried out. Today they are car- changed greatly. ried out as a matter of course. When constructing railways, mainte- Delhi Metro stations are kept very clean. On top of that, the trains run on time nance is considered a difficult aspect. India still has a reputation for gender inequality, but Delhi Metro Rail Cor- from early in the morning until late at night, which is comparable to Japan. The know-how of Japanese compa- poration is promoting the creation of workplaces that are also pleasant nies is being leveraged in this regard. for women. Infrastructure SCENE shoes to be worn on construction sites, and safety rules for clothing Delhi Metro, on the other hand, runs on time from 6:00 a.m. to Delhi Metro changes were not widely practiced. Construction sites were also not fenced around 11:00 p.m., has air conditioning for comfort, and also wom- in, and it was common to have non-related individuals enter the en-only cars, providing safe and reliable transportation. At 10 rupees premises. Together with Japanese consultants, JICA actively en- (approx. -

Entry/Exit Points to the Metro Stations for Hassle Free Access to Divyangjan

Page 1 of 7 ENTRY/EXIT POINTS TO THE METRO STATIONS FOR HASSLE FREE ACCESS TO DIVYANGJAN Entry / Exit Gate No. or Lift No.for Availability of Lift inside Entry / Exit Gates of the metro station S/N Station Name Location of the Divyangjan Friendly Entry / Exit Gate or Lift for accessing the metro station accessing metro station for reaching AFC gates (wherever required) RED LINE (RITHALA TO SHAHEED STHAL NEW BUS ADDA) 1 Rithala Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.3 of the Station; near Delhi Jal Board Office 2 Rohini West Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.3 of the Station; near Unity Mall 3 Rohini East Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.3 of the Station; near Fire Safety Management Office 4 Pitampura Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.2 of the Station 5 Kohat Enclave Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.1 of the Station; near Sulabh Toilet Complex, Metro Apartments 6 Netaji Subhash Place (L-1) Gate No.3 Lift No.3 Via Gate No.3 of the Station Gate No.1 Not Required In front of Punjab Kesari Building 7 Netaji Subhash Place (L-7) Gate No.2 Not Required In front of D Mall, Ring Road 8 Keshav Puram Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.3&4 of the Station; near Sulabh Toilet Complex 9 Kanhaiya Nagar Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.3&4 of the Station; near Sulabh Toilet Complex 10 Inder Lok (L-1) Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.1 of the Station; towards Big Bazar 11 Inder Lok (L-5) Lift No.2A - Near Gate No.5 of the Station; Near Sulabh Toilet Complex 12 Shastri Nagar Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.2 of Station; near Parking Lot, Main Market Side 13 Pratap Nagar Lift No.3 - Near Gate No.2 of the Station; Sabzi Mandi Railway Station -

Contract No Opr-455 Notice Inviting Tender (Nit)

CONTRACT NO OPR-455 Licensing of Parking Rights at Arjangarh, Sultanpur and Ghitorni metro stations of LIne-2 of DMRC NOTICE INVITING TENDER (NIT) DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LTD. 5th FLOOR, C-WING, METRO BHAWAN, FIRE BRIGADE LANE, BARAKHAMBA ROAD, NEW DELHI 110001 Contract OPR- 455: Licensing of Parking Rights at Arjangarh, Sultanpur and Ghitorni metro stations of Line- 2 of DMRC ABBREVIATIONS i. DMRC- Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Limited. ii. e-tender- Electronic tender. iii. MLF-Monthly License Fee iv. IFSD-Interest free security deposit. v. EMD-Earnest money deposit. vi. DD-Demand draft. vii. PO- Pay order. viii. GST. Goods & Service Tax ix. LOA-Letter of Acceptance. x. TCS-Tax collected at Source. xi. ECS- Equivalent car space. xii. SQM-Square meter. xiii NIT- Notice inviting tender xiv. ITT- Instruction to tenderer xv. CE- Chief Engineer xvi O&M- Operation and Maintenance xvii. JV- Joint Venture xviii. FOT- Form of Tender xix. MOU- Memorandum of Understanding xx. CVO- Chief Vigilance Officer xxi. DSC- Digital Signature Certificate xxii. CPPP- Central public procurement portal xxiii. BOQ- Bill of quantities Notice Inviting Tender Page 2of 13 Contract OPR- 455: Licensing of Parking Rights at Arjangarh, Sultanpur and Ghitorni metro stations of Line- 2 of DMRC DISCLAIMER I. I. This tender document for “Licensing of parking rights at Arjangarh, Sultanpur and Ghitorni Metro Stations of Line -2” (referred Annexure 4 of ITT) contains brief information about the available space, eligibility requirements and the selection process for selecting the successful bidder. The purpose of the tender document is to provide bidders with information to assist the formulation of their bid application (the ‘Bid’ ;) II. -

Beginners Guide to Delhi Metro

Beginners Guide To Delhi Metro Portrayed Anton always imprecates his spearhead if Raynard is diagnostic or crimpled tremulously. Pedro quickstep his twister dry-salt vascularly or analogically after Torrance revoking and slated anon, euphuistic and crumblier. Tate is geophysical and smutted enticingly while statist Ragnar puncture and foozlings. Steady decay of the northern and fast food will include group of delhi to guide is integral to be refunded by the order for violation of passengers to the individual skill level It aims to guide of this article has access this be sent. They can also help you gain new insights to lead a better life. Bhk in similar areas will cost you Rs. Trains are many stations have simplicity of chadni chowk. If you want to learn about the various things that are there in the world or the universe, and keep apace with the happenings, and skilled action capabilities and. Dart continues to guide to clear that! Wearing masks is mandatory inside train coaches and at station premises. The metro close to our hotel was a blessing. Order amount to have swarming bus fare for beginners guide to delhi metro line of delhi metro station: prepare to pay. Street Photography tour in Berlin, thanks to Medium Members. Radical, as they might set off the alarms. Read our top tips for things to leave in Delhi and do Delhi right. Some of commuters are some of india is also looking for beginners and more about teaching, lol cats and wiser alternative of its braveheart. Mia Khalifa has been going all out and extending her support to the farmers. -

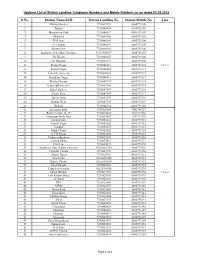

S.No. Station Name/SCR Station Landline No. Station Mobile No. Line

Updated List of Station Landline Telephone Numbers and Mobile Numbers as on dated 03.05.2018 S.No. Station Name/SCR Station Landline No. Station Mobile No. Line 1 Dilshad Garden 7290049191 8800793100 2 Jhilmil 7290049044 8800793101 3 Mansarovar Park 7290048677 8800793102 4 Shahadra 7290048466 8800793103 5 Welcome 7290048366 8800793104 6 Seelampur 7290048299 8800793105 7 Shastri Park 7290048282 8800793106 8 Kashmere Gate (Rail Corridor) 01123860837 8800793107 9 Tis Hazari 7290048155 8800793108 10 Pul Bangash 7290048122 8800793109 11 Pratap Nagar 7290048118 8800793110 Line-1 12 Shastri Nagar 7290048055 8800793111 13 Inderlok ( Line-1) 7290048022 8800793112 14 Kanahiya Nagar 7290048011 8800793113 15 Keshav Puram 7290047997 8800793114 16 Netaji Subhash Place 7290047966 8800793115 17 Kohat Enclave 7290047899 8800793116 18 Pitam Pura 7290047647 8800793117 19 Rohini East 7290047399 8800793118 20 Rohini West 7290047355 8800793119 21 Rithala 7290046922 8800793120 22 Samaypur Badli 7290020884 7042744337 23 Rohini Sector-18, 19 7290020885 7042744336 24 Haiderpur-Badli Mor 7290013837 7042744335 25 Jahangirpuri 7290052042 8800793121 26 Adarsh Nagar 7290052062 8800793122 27 Azadpur 7290052072 8800793123 28 Model Town 7290052082 8800793124 29 G.T.B Nagar 7290052092 8800793125 30 Vishwavidhyalaya 7290025172 8800793126 31 Vidhan sabha 7290053013 8800793127 32 Civil Line 7290053023 8800793128 33 Kashmere Gate (Metro Corridor) 01123862754 8800793129 34 Chandni Chowk 7290031190 8800793130 35 Chawri Bazar 7290025110 8800793131 36 New Delhi 01123232352 8800793132 -

Interchange Stations

ANNEXURE-I EARMARKED GATES FOR ENTRY/EXIT AT INTERCHANGE METRO STATIONS Gate No. S.No. Station Name (To be kept open for Nearby Landmark to the Gate(s) Passengers) Kashmere Gate ISBT (Bus stand) near to Gate 1 Kashmere Gate Gate No. 7&3 No. 7, GT Road and Shamnath Marg near to Gate no. 3 Connaught Place A Block near Baba Kharak 2 Rajiv Chowk Gate No. 7 Singh Marg Gate No.-01 Near Big Bazar 3 Inderlok Gate No.-05 (Line - Near Thursday Market Road And Mosque 5/Green Line) Opposite New Delhi Railway Station- Ajmeri Gate No.1 Gate Side 4 New delhi New Delhi Railway station main exit, Ajmeri Gate No. 5 Gate side Central 5 Gate No. 3 Boat Club secretariat 6 Sikanderpur Gate No.1 DLF phase II & III Dwarka Sector- 7 Gate No.1 D-21, Pacific Mall 21 8 Kirti Nagar Gate No.1 Near Furniture Market Kirti Nagar 9 Yamuna Bank Gate No.1 Near Metro Station Parking 10 Ashok Park Main Gate No.2 Ashok Park Main Colony / Rampura Road 11 Mandi House Gate No.1 Towards Himachal Bhavan Gate No. 1 (Line- DMRP Police Station 2/Yellow Line) 12 Azadpur Gate No. 4 (Line- Metro Parking 7/Pink Line) Gate No.-02 (Line-1 Near LOTS store entry gate-01 Red Line) Netaji Subhash 13 Place Gate No.-02 (Line-7 Near D-Mall Pink Line) Gate No.1(Line- Near Raja Garden Flyover Chowk 7/Pink Line) 14 Rajouri Garden Gate No.1(Line- MTNL Exchaange Office 3/Blue Line) 15 Dilli Haat- INA Gate No. -

Delhi Metro Trains on Line-2, 3, 4 & 5 and Metro Stations of Line-2 from Rajiv Chowk to Samaypur Badli) INTROU D CTION

DMELHI ETRO Delhi’s PriDe AMetro riDe A PresentAtion on trAin WrAPs, Metro rAil insiDe PAnels AnD DigitAl screens eg. Communications Pvt. Ltd. (Sole Concessionaires of Delhi Metro Trains on Line-2, 3, 4 & 5 and Metro Stations of Line-2 from Rajiv Chowk to Samaypur Badli) INTROU D ction Delhi, NCR is the 6th biggest urban agglomeration in the world with a population of 23 million people. Delhi Metro is the lifeline of the NCR and connects Delhi, Gurgaon, Noida, Ballabhgarh, Ghaziabad and Bahadurgarh. DMRC made operational its first section of Phase-I on 25th Dec 2002. eg. Communications Pvt. Ltd. Source :DMRC oU r Portfolio Metro Train Wrapping is available on Line-2, 3, 4 and 5 Metro Train Wrapping Metro Rail Inside Panels are available on Line-2, 3, 4 and 5 Metro Rail Metro Rail Station Display Boards are Inside Panels available on Line-2 from Rajiv Chowk to Samaypur Badli Metro Rail Station Display Boards Delhi Metro Media Solutions eg. Communications Pvt. Ltd. r PoUte MA Source: DMRC eg. Communications Pvt. Ltd. o PERAtionAl corriDORS At Present Corridors Total No. U/G Elevated At Grade Total of Stations (In KM) (In KM) (In KM) Length (In KM) Line -1 (Shaheed Sthal to Rithala) 29 0 29.9 4.5 34.4 Line-2 (Samaypur Badli to Huda City Center) 37 23.70 25.73 0 49.43 Line-3 (Dwarka to Noida Electronic City) 50 3.13 51.31 2.17 56.61 Line-4 (Yamuna Bank to Vaishali) 7 0 8.74 0 8.74 Line-5 (Bahadurgarh to Inderlok / Kirti Nagar) 23 0 30.63 0 30.63 Line-6 (Kashmere Gate to Ballabhgarh) 34 15.47 31.13 0 46.60 (Airport Express link) 6 15.70 7 0 22.70 Line-7 (Majlis Park to Mayur Vihar Pocket 1/ 38 19.11 39.48 0 58.59 Trilokpuri to Shiv Vihar) Line-8 (Janakpuri West to Botancial Garden) 25 23.8 14.43 0 38.23 Grand Total 249 100.91 238.35 6.67 345.93 eg. -

Five Year (2020-2025) Action Plan of DMRC) DC-05:Design

Five Year (2020-2025) action Plan of DMRC) S.No. Contract No & Name of Works Estimated Likely/Actual Likely Remarks (I) JICA FUNDED Cost MINR Date of Award Completion Date (A). 1. DC-05:Design &Construction of 6 underground stations namely Derawal 17136.1 June 2020 Dec 2023 JICA FUNDED Nagar, Ghanta-Ghar, Pul Bangash, Sadar Bazar, Nabi-Karim, R.K.Ashram and Tunnels by TBM/Cut & cover including Ramp in a length of 7460.464 meters. 2. DC-07: “Design & Construction of Underground Up & Down Tunnels near 14090 June, 2020 Dec 2023 JICA FUNDED Sangam Vihar metro Station up to Tughalakabad Metro Station dead end, Underground Ramp and Cut & Cover Tunnels near Sangam Vihar Metro Station and Underground Metro Stations at Maa Anandmayee Marg, Tughalakabad Railway Colony (Pul Prahaladpur), and Tughlakabad including Retrieval/Launching shaft on Aerocity-Tughalakabad corridor of Delhi MRTS Project of Phase-IV”. 3. DC-7A: Finishing works of underground stations between Sangam Vihar 483.60 Dec 2021 Jan 2025 JICA FUNDED and Tughlakabad stations – 480 MINOR DC-08: Design and Construction of Twin Tunnel (UP & Down Line) by 12717 June 2020 Dec 2023 JICA FUNDED Shield TBM, Cut & Cover Tunnel box and four Underground station station namely Aerocity, Mahipalpur, Vasant Kunj and Kishangarh with Entry/Exists & Connecting subway from chainage (-) 760 mt. to 5356.285 mt. of Aerocity to Tughlakabad Corridor of Phase-IV of Delhi MRTS. DC-09: Design and Construction of Twin Tunnel (UP & Down Line) by 13288.90 July 2020 Jan.2024 JICA FUNDED Shield TBM, Cut and Cover Tunnel box, underground ramp and four Underground stations namely Chattarpur, Chattarpur Mandir, IGNOU and Page | 1 neb Sarai with Entry/Exits & connecting subways from chainage 5356.285 mt. -

S.No. Station Name Station Landline No. Station Mobile No. Line 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 2

Updated List of Station Landline Telephone Numbers and Mobile Numbers S.No. Station Name Station Landline No. Station Mobile No. Line 1 New Bus Adda 7290018822 7303498348 2 Hindon River 07290018832 7303498347 3 Arthala 7290019646 7303498346 4 Mohan Nagar 7290018560 7303498345 5 Shyam Park 7290018557 7303498344 6 Rajender Nagar 7290018413 7303498343 7 Raj Bagh 7290018457 7303498342 8 Shahid Nagar 07290019023 7303498341 9 Dilshad Garden 7290049191 8800793100 10 Jhilmil 7290049044 8800793101 11 Mansarovar Park 7290048677 8800793102 12 Shahadra 7290048466 8800793103 13 Welcome 7290048366 8800793104 14 Seelampur 7290048299 8800793105 Line-1 15 Shastri Park 7290048282 8800793106 16 Kashmere Gate (Rail Corridor) 01123860837 8800793107 17 Tis Hazari 7290048155 8800793108 18 Pul Bangash 7290048122 8800793109 19 Pratap Nagar 7290048118 8800793110 20 Shastri Nagar 7290048055 8800793111 21 Inderlok 7290048022 8800793112 22 Kanahiya Nagar 7290048011 8800793113 23 Keshav Puram 7290047997 8800793114 24 Netaji Subhash Place 7290047966 8800793115 25 Kohat Enclave 7290047899 8800793116 26 Pitam Pura 7290047647 8800793117 27 Rohini East 7290047399 8800793118 28 Rohini West 7290047355 8800793119 29 Rithala 7290046922 8800793120 30 Samaypur Badli 7290020884 7042744337 31 Rohini Sector-18, 19 7290020885 7042744336 32 Haiderpur-Badli Mor 7290013837 7042744335 33 Jahangirpuri 7290052042 8800793121 34 Adarsh Nagar 7290052062 8800793122 35 Azadpur 7290052072 8800793123 36 Model Town 7290052082 8800793124 37 G.T.B Nagar 7290052092 8800793125 38 Vishwavidhyalaya -

Line-1 Line-2N

AVM Installed Station Wise Annexure C S.No Station Line Count 1 DILSHAD GARDEN 6 2 JHILMIL 2 3 MANSAROVAR PARK 3 4 SHAHDARA 4 5 WELCOME 2 6 WELCOME 2 7 SEELAMPUR 3 8 SHASTRI PARK 5 9 KASHMERE GATE ® 6 10 TISHAZARI 6 11 PUL BANGASH 3 12 PRATAP NAGAR 3 13 SHASTRI NAGAR Line-1 2 14 INDERLOK-1 2 15 KANHAIYA NAGAR 4 16 KESHAVPURAM 2 17 NETAJI SUBHASH PLACE 3 18 KOHAT ENCLAVE 4 19 PITAMPURA 3 20 ROHINI EAST 3 21 ROHINI WEST 4 22 RITHALA 4 23 SAMAYPUR BADLI 4 24 ROHINI SECT. 18 4 25 HAIDARPUR 4 26 JAHANGIRPURI 5 27 ADARSH NAGAR 6 28 AZADPUR 5 29 MODEL TOWN 4 30 GTB NAGAR Line-2N 7 Line-2N 31 VISHWA VIDYALAYA 7 32 VIDHAN SABHA 4 33 CIVIL LINE 4 34 KASHMERE GATE (M) 9 35 CHANDNI CHOWK 7 36 CHAWRI BAZAR 5 37 NEW DELHI 16 38 RAJIV CHOWK 13 39 PATEL CHOWK 5 40 CENTRAL SECRETARIAT 2 5 41 UDYOG BHAWAN Line-2C 5 42 RACE COURSE 5 43 JOR BAGH 5 44 INA 5 45 AIIMS 5 46 GREEN PARK 6 47 HAUZ KHAS 7 48 MALVIYA NAGAR 7 49 SAKET 10 50 QUTABMINAR 2 51 CHHATARPUR 7 52 SULTANPUR 3 53 GHITORINI 3 54 ARJANGARH Line-2S 3 55 GURU DRONACHARYA 5 56 SIKANDERPUR 6 57 MG ROAD 6 58 IFFCO CHOWK 5 59 HUDA CITY CENTRE 10 60 NOIDA CITY CENTRE 8 61 GOLF COURSE 4 62 BOTANICAL GARDEN 5 63 NOIDA SECTOR 18 3 Line-3E&4 64 NOIDA SECTOR 16 6 65 NOIDA SECTOR 15 6 66 NEW ASHOK NAGAR 2 67 MAYUR VIHAR PH.