Fighting Covid 19 in Adaklu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of the Adaklu-Anyigbe Conflict. by Noble

The Dynamics of Communal Conflicts in Ghana's Local Government System: A Case Study of the Adaklu-Anyigbe Conflict. by Noble Kwabla Gati Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the Award of Master of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Transformation MPCT 2006-2008 Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tromsø, Norway ii The Dynamics of Communal Conflicts in Ghana's Local Government System: A Case Study of the Adaklu-Anyigbe Conflict. By Noble Kwabla Gati Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the Award of Master of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Transformation MPCT 2006-2008 Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Social Science, University of Tromsø, Norway iii iv DEDICATION To My late Mum, with much love and appreciation . v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TO GOD BE THE GLORY, HONOUR AND PRAISE! Diverse contributions by many people have culminated in the writing of this thesis. I therefore deem it fit to render my appreciation to those people. I am highly indebted of appreciation to my siblings, especially Dela Gati, whose contribution to my life cannot be written off. His selfless dedication to the cause of my academic life has greatly contributed to bringing me this far on the academic ladder. God bless you, Dela. In fact, the role of my supervisor Tone Bleie is very noteworthy. Your constructive criticisms, compliments and encouragements throughout the writing process are well noted and appreciated. Your keen interest in my health issues has also been very remarkable. In deed, you have demonstrated to me that you are not only interested in my academic work, but also my well- being. -

GNHR) P164603 CR No 6337-GH REF No.: GH-MOGCSP-190902-CS-QCBS

ENGAGEMENT OF A FIRM FOR DATA COLLECTION IN THE VOLTA REGION OF GHANA FOR THE GHANA NATIONAL HOUSEHOLD REGISTRY (GNHR) P164603 CR No 6337-GH REF No.: GH-MOGCSP-190902-CS-QCBS I. BACKGROUND & CONTEXT The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MGCSP) as a responsible institution to coordinate the implementation of the country’s social protection system has proposed the establishment of the Ghana National Household Registry (GNHR), as a tool that serves to assist social protection programs to identify, prioritize, and select households living in vulnerable conditions to ensure that different social programs effectively reach their target populations. The GNHR involves the registry of households and collection of basic information on their social- economic status. The data from the registry can then be shared across programs. In this context, the GNHR will have the following specific objectives: a) Facilitate the categorization of potential beneficiaries for social programs in an objective, homogeneous and equitable manner. b) Support the inter-institutional coordination to improve the impact of social spending and the elimination of duplication c) Allow the design and implementation of accurate socioeconomic diagnoses of poor people, to support development of plans, and the design and development of specific programs targeted to vulnerable and/or low-income groups. d) Contribute to institutional strengthening of the MoGCSP, through the implementation of a reliable and central database of vulnerable groups. For the implementation of the Ghana National Household Registry, the MoGCSP has decided to use a household evaluation mechanism based on a Proxy Means Test (PMT) model, on which welfare is determined using indirect indicators that collectively approximate the socioeconomic status of individuals or households. -

National Communications Authority List Of

NATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY LIST OF AUTHORISED VHF-FM RADIO STATIONS IN GHANA AS AT THIRD QUARTER, 2019 Page 1 of 74 OVERVIEW OF FM RADIO BROADCASTING STATIONS IN GHANA Section 2 of the Electronic Communications Act, 2008, Act 775 mandates that the National Communications Authority “shall regulate the radio spectrum designated or allocated for use by broadcasting organisations and providers of broadcasting services”; “… determine technical and other standards and issue guidelines for the operation of broadcasting organisations …” “… may adopt policies to cater for rural communities and for this purpose may waive fees wholly or in part for the grant of a frequency authorisation”. The Broadcasting service is a communication service in which the transmissions are intended for direct reception by the general public. The sound broadcasting service involves the broadcasting of sound which may be accompanied by associated text/data. Sound broadcasting is currently deployed in Ghana using analogue transmission techniques: Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM). Over the last two decades, AM sound broadcasting has faded, leaving FM radio as the only form of sound broadcasting in Ghana. FM radio broadcasting stations are classified for the purpose of regulatory administration of the service towards the attainment of efficient use of frequency. The following is the classification of FM radio broadcasting stations in Ghana. (1) Classification by Purpose: a) Public – all stations owned and operated by the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) and/or any other station established by the Government of Ghana by a statutory enactment. b) Public Foreign – stations established by Foreign Governments through diplomatic arrangements to rebroadcast/relay content from foreign countries e.g. -

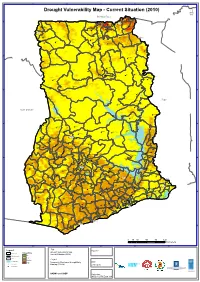

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

2021 PES Field Officer's Manual Download

2021 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS POST ENUMERATION SURVEY (PES) FIELD OFFICER’S MANUAL STATISTICAL SERVICE, ACCRA July, 2021 1 Table of Content LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................. 13 1. THE CONCEPT OF PES AND OVERVIEW OF CENSUS EVALUATION ........................ 13 1.1 What is a Population census? .................................................................................................. 13 1.2 Why are we conducting the Census? ...................................................................................... 13 1.3. Census errors .............................................................................................................................. 13 1.3.1. Omissions ................................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.2. Duplications ............................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.3. Erroneous inclusions ............................................................................................................... 15 1.3.4. Gross versus net error ............................................................................................................ -

ADAKLU DISTRICT ASSEMBLY SUB -PROGRAMME 1.4 Legislative Oversights

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 4 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE DISTRICT ................................................................................ 4 2. POPULATION STRUCTURE .............................................................................................. 4 3. DISTRICT ECONOMY ....................................................................................................... 5 a. AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................. 5 REPUBLIC OF GHANA b. Industry........................................................................................................................ 6 d. TOURISM .......................................................................................................................... 7 e. ROAD NETWORK ......................................................................................................... 8 COMPOSITE BUDGET f. EDUCATION ................................................................................................................. 8 f. HEALTH ........................................................................................................................ 9 g. WATER AND SANITATION ........................................................................................ 10 FOR 2019-2022 h. ENERGY .................................................................................................................... -

National Communications Authority List Of

NATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY LIST OF AUTHORISED VHF-FM RADIO STATIONS IN GHANA AS AT SECOND QUARTER, 2019 Page 1 of 73 OVERVIEW OF FM RADIO BROADCASTING STATIONS IN GHANA Section 2 of the Electronic Communications Act, 2008, Act 775 mandates that the National Communications Authority “shall regulate the radio spectrum designated or allocated for use by broadcasting organisations and providers of broadcasting services”; “… determine technical and other standards and issue guidelines for the operation of broadcasting organisations …” “… may adopt policies to cater for rural communities and for this purpose may waive fees wholly or in part for the grant of a frequency authorisation”. The Broadcasting service is a communication service in which the transmissions are intended for direct reception by the general public. The sound broadcasting service involves the broadcasting of sound which may be accompanied by associated text/data. Sound broadcasting is currently deployed in Ghana using analogue transmission techniques: Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM). Over the last two decades, AM sound broadcasting has faded, leaving FM radio as the only form of sound broadcasting in Ghana. FM radio broadcasting stations are classified for the purpose of regulatory administration of the service towards the attainment of efficient use of frequency. The following is the classification of FM radio broadcasting stations in Ghana. (1) Classification by Purpose: a) Public – all stations owned and operated by the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) and/or any other station established by the Government of Ghana by a statutory enactment. b) Public Foreign – stations established by Foreign Governments through diplomatic arrangements to rebroadcast/relay content from foreign countries e.g. -

Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into the Creation of New Regions

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS EQUITABLE DISTRIBUTION OF NATIONAL RESOURCES FOR BALANCED DEVELOPMENT PRESENTED TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO ON TUESDAY, 26TH DAY OF JUNE, 2018 COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO In case of reply, the CREATION OF NEW REGIONS number and date of this Tel: 0302-906404 Letter should be quoted Email: [email protected] Our Ref: Your Ref: REPUBLIC OF GHANA 26th June, 2018 H.E. President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo President of the Republic of Ghana Jubilee House Accra Dear Mr. President, SUBMISSION OF THE REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS You appointed this Commission of Inquiry into the Creation of New Regions (Commission) on 19th October, 2017. The mandate of the Commission was to inquire into six petitions received from Brong-Ahafo, Northern, Volta and Western Regions demanding the creation of new regions. In furtherance of our mandate, the Commission embarked on broad consultations with all six petitioners and other stakeholders to arrive at its conclusions and recommendations. The Commission established substantial demand and need in all six areas from which the petitions emanated. On the basis of the foregoing, the Commission recommends the creation of six new regions out of the following regions: Brong-Ahafo; Northern; Volta and Western Regions. Mr. President, it is with great pleasure and honour that we forward to you, under the cover of this letter, our report titled: “Equitable Distribution of National Resources for Balanced Development”. -

Location of Farmers Warehouse at Adaklu Traditional Area, Volta Region, Ghana

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Optimization Volume 2016, Article ID 2459734, 10 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/2459734 Research Article Location of Farmers Warehouse at Adaklu Traditional Area, Volta Region, Ghana Vincent Tulasi,1 Isaac Kwasi Adu,2 and Elikem Kofi Krampa1 1 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Ho Polytechnic, Ho, Ghana 2Department of Mathematics, Valley View University, Techiman Campus, Techiman, Ghana Correspondence should be addressed to Vincent Tulasi; [email protected] Received 2 December 2015; Revised 29 March 2016; Accepted 14 April 2016 Academic Editor: Manlio Gaudioso Copyright © 2016 Vincent Tulasi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Postharvest loss is one major problem farmers in Adaklu Traditional Area that most Ghanaian farmers face. As a result, many farmers wallow in abject poverty. Warehouses are important facilities that help to reduce postharvest loss. In this research, Beresnev pseudo-Boolean Simple Plant Location Problem (SPLP) model is used to locate a warehouse at Adaklu Traditional Area, Volta Region, Ghana. This model was used because it gives a straightforward computation and produces no iteration as compared with other models. The SPLP is a problem of selecting a site from candidate sites to locate a plant so that customers can be supplied from the plant at a minimum cost. The model is made up of fixed cost and transportation cost. Location index ordering matrix was developed from the transportation cost matrix and we used it with the fixed cost and differences between variable costs to formulate the Beresnev function. -

National Communications Authority List Of

NATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY LIST OF AUTHORISED VHF-FM RADIO STATIONS IN GHANA AS AT SECOND QUARTER, 2017 Page 1 of 82 OVERVIEW OF FM RADIO BROADCASTING STATIONS IN GHANA Section 2 of the Electronic Communications Act, 2008, Act 775 mandates that the National Communications Authority “shall regulate the radio spectrum designated or allocated for use by broadcasting organisations and providers of broadcasting services”; “… determine technical and other standards and issue guidelines for the operation of broadcasting organisations …” “… may adopt policies to cater for rural communities and for this purpose may waive fees wholly or in part for the grant of a frequency authorisation”. The Broadcasting service is a communication service in which the transmissions are intended for direct reception by the general public. The sound broadcasting service involves the broadcasting of sound which may be accompanied by associated text/data. Sound broadcasting is currently deployed in Ghana using analogue transmission techniques: Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM). Over the last two decades, AM sound broadcasting has faded, leaving FM radio as the only form of sound broadcasting in Ghana. FM radio broadcasting stations are classified for the purpose of regulatory administration of the service towards the attainment of efficient use of frequency. The following is the classification of FM radio broadcasting stations in Ghana. (1) Classification by Purpose: a) Public – all stations owned and operated by the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) and/or any other station established by the Government of Ghana by a statutory enactment. b) Public Foreign – stations established by Foreign Governments through diplomatic arrangements to rebroadcast/relay content from foreign countries e.g. -

The Office of the Head of Local Government Service

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE OFFICE OF THE HEAD OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICE MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2017-2019 2017 BUDGET ESTIMATES For copies of the LGS MTEF PBB Estimates, please contact the Public Relations Office of the Ministry: Ministry of Finance Public Relations Office New Building, Ground Floor, Room 001/ 003 P. O. Box MB 40, Accra – Ghana The LGS MTEF PBB Estimate for 2017 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh Local Government Service Page ii Table of Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF THE HEAD OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICE (OHLGS) .......................................................................................1 1. GSGDA II POLICY OBJECTIVES .............................................................................. 1 2. GOAL .................................................................................................................. 1 3. CORE FUNCTIONS ............................................................................................... 1 4. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS .................................................... 2 5. EXPENDITURE TRENDS ......................................................................................... 3 6. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS FOR 2016 ............................................................................ 4 PART B: BUDGET PROGRAM SUMMARY ...........................................................................5 PROGRAM 1: MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION .................................................. 5 PROGRAMME -

Manufacturing Capabilities in Ghana's Districts

Manufacturing capabilities in Ghana’s districts A guidebook for “One District One Factory” James Dzansi David Lagakos Isaac Otoo Henry Telli Cynthia Zindam May 2018 When citing this publication please use the title and the following reference number: F-33420-GHA-1 About the Authors James Dzansi is a Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC), Ghana. He works with researchers and policymakers to promote evidence-based policy. Before joining the IGC, James worked for the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change, where he led several analyses to inform UK energy policy. Previously, he served as a lecturer at the Jonkoping International Business School. His research interests are in development economics, corporate governance, energy economics, and energy policy. James holds a PhD, MSc, and BA in economics and LLM in petroleum taxation and finance. David Lagakos is an associate professor of economics at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). He received his PhD in economics from UCLA. He is also the lead academic for IGC-Ghana. He has previously held positions at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis as well as Arizona State University, and is currently a research associate with the Economic Fluctuations and Growth Group at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His research focuses on macroeconomic and growth theory. Much of his recent work examines productivity, particularly as it relates to agriculture and developing economies, as well as human capital. Isaac Otoo is a research assistant who works with the team in Ghana. He has an MPhil (Economics) from the University of Ghana and his thesis/dissertation tittle was “Fiscal Decentralization and Efficiency of the Local Government in Ghana.” He has an interest in issues concerning local government and efficiency.