'What Really Happened Ain't There': Sifting the Lies of Settler Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

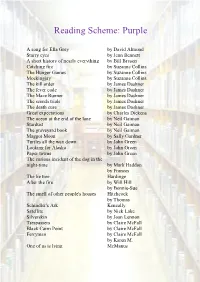

Reading Scheme: Purple

Reading Scheme: Purple A song for Ella Grey by David Almond Starry eyes by Jenn Bennett A short history of nearly everything by Bill Bryson Catching fire by Suzanne Collins The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins Mockingjay by Suzanne Collins The kill order by James Dashner The fever code by James Dashner The Maze Runner by James Dashner The scorch trials by James Dashner The death cure by James Dashner Great expectations by Charles Dickens The ocean at the end of the lane by Neil Gaiman Stardust by Neil Gaiman The graveyard book by Neil Gaiman Maggot Moon by Sally Gardner Turtles all the way down by John Green Looking for Alaska by John Green Paper towns by John Green The curious incident of the dog in the night-time by Mark Haddon by Frances The lie tree Hardinge After the fire by Will Hill by Bonnie-Sue The smell of other people's houses Hitchcock by Thomas Schindler's Ark Keneally Satellite by Nick Lake Silverskin by Joan Lennon Trespassers by Claire McFall Black Cairn Point by Claire McFall Ferryman by Claire McFall by Karen M. One of us is lying McManus by Herman Moby-Dick Melville by Michael Private Peaceful Morpurgo by Michael War Horse Morpurgo The Ask and the Answer by Patrick Ness The Knife of Never Letting Go by Patrick Ness Monsters of men by Patrick Ness A monster calls: a novel by Patrick Ness Things a bright girl can do by Sally Nicholls Animal Farm by George Orwell by Christopher Eragon Paolini by Christopher Eldest Paolini by Christopher Eragon Paolini by Christopher Brisingr Paolini by Christopher Inheritance, or the vault of souls Paolini Life: an exploded diagram by Mal Peet The last days of Archie Maxwell by Annabel Pitcher My sister lives on the mantlepiece by Annabel Pitcher Northern lights by Philip Pullman Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children by Ranson Riggs Allegiant by Veronica Roth Divergent by Veronica Roth Insurgent by Veronica Roth by Marcus Saint Death Sedgwick Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift Finding Violet Park by Jenny Valentine by Benjamin Gangsta rap Zephaniah . -

Senior School Book Ideas

Senior School Book Ideas Senior School Book Ideas General Fiction: Douglas Adams The Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy (6 books) J. G. Ballard Empire of the Sun Nina Bawden Carrie’s War The Witch’s Daughter Malorie Blackman Noughts & Crosses Series (3 books) Noble Conflict Pig Heart Boy And many more by this author… Leigh Bardugo The Book of Crows Senior School Book Ideas John Boyne The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas The Boy at the Top of the Mountain Ray Bradbury The Illustrated Man Chris Bradford The Bodyguard Series (8 Books) Recruit Ransom Ambush Terry Brooks The Magic Kingdom of Landover Series (6 Books) The Magic Kingdom for Sale The Black Unicorn Wizard at Large David Clement-Davies Fire Bringer Stephen Cole Thieves Like Us Senior School Book Ideas Suzanne Collins The Hunger Games (3 Books) Hunger Games Catching Fire Mockingjay Bernard Cornwell The Sharpe series (20 books) Sharpe’s Devil Sharpe’s Triumph Sharpe’s Fortress Joseph Delaney The Wardstone Chronicles ( 13 books) The Spooks Apprentice The Spooks Curse The Spook’s Secret Anita Desai The Village by the Sea Jostein Gaarder Sophie’s World The Solitaire Mystery Neil Gaiman Coraline Stardust Good Omens The Graveyard Book Neverwhere Senior School Book Ideas Sally Gardner Maggot Moon Roderick Gordon & Tunnels Series (9 books) Brian Williams Tunnels Deeper Closer Michael Grant Gone Series (6 books) Gone Hunger Lies John Grisham Theodore Boone (6 books) Theodore Boone The Abduction The Activist Mark Haddon The Curious Incident of the Dog -

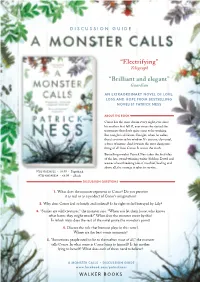

“Electrifying” “Brilliant and Elegant”

Discussion Gui D e “Electrifying” Telegraph “Brilliant and elegant” Guardian An ExTraordinAry nOvEl Of lOvE, lOss And hopE frOm besTsElling nOvElisT PatricK Ness ABOUT THE BOOK Conor has the same dream every night, ever since his mother first fell ill, ever since she started the treatments that don’t quite seem to be working. But tonight is different. Tonight, when he wakes, there’s a visitor at his window. It’s ancient, elemental, a force of nature. And it wants the most dangerous thing of all from Conor. It wants the truth. Bestselling novelist Patrick Ness takes the final idea of the late, award-winning writer Siobhan Dowd and weaves a heartbreaking tale of mischief, healing and above all, the courage it takes to survive. 9781406336511 • £6.99 • Paperback 9781406345834 • £6.99 • eBook discUssiOn QuesTiOns 1. What does the monster represent to Conor? Do you perceive it as real or as a product of Conor’s imagination? 2. Why does Conor feel so lonely and isolated? Is he right to feel betrayed by Lily? 3. “Stories are wild creatures,” the monster says. “When you let them loose, who knows what havoc they might wreak?” What does the monster mean by this? In which ways does the rest of the novel prove the monster’s point? 4. Discuss the role that humour plays in this novel. Where are the best comic moments? 5. “Sometimes people need to lie to themselves most of all,” the monster tells Conor. In what sense is Conor lying to himself? Is his mother lying to herself? What does each of them need to believe? A Monster Calls • discUssiOn GuidE www.facebook.com/patrickness Discussion Gui D e 6. -

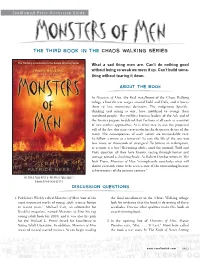

The THIRD Book in the Chaos Walking SERIES

Candlewick Press Discussion Guide The THIRD book in The Chaos Walking SERIES What a sad thing men are. Can’t do nothing good without being so weak we mess it up. Can’t build some- thing without tearing it down. ABOUT THE BOOK In Monsters of Men, the final installment of the Chaos Walking trilogy, a horrific war surges around Todd and Viola, and it forces them to face monstrous decisions. The indigenous Spackle, thinking and acting as one, have mobilized to avenge their murdered people. The ruthless human leaders of the Ask and of the Answer prepare to defend their factions at all costs as a convoy of new settlers approaches. As is often true in war, the projected will of the few threatens to overwhelm the desperate desire of the many. The consequences of each action are unspeakably vast: To follow a tyrant or a terrorist? To save the life of the one you love most, or thousands of strangers? To believe in redemption, or assume it is lost? Becoming adults amid the turmoil, Todd and Viola question all they have known, racing through horror and outrage toward a shocking finale. As Robert Dunbar writes in The Irish Times, Monsters of Men “triumphantly concludes what will almost certainly come to be seen as one of the outstanding literary achievements of the present century.” HC: 978-0-7636-4751-3 • PB: 978-0-7636-5665-2 E-book: 978-0-7636-5211-1 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Publishers Weekly called Monsters of Men “one of the the final installment in the Chaos Walking trilogy, most important works of young adult science fiction look for evidence that the book is deserving of these in recent years.” Michael Cart, an editorialist for accolades. -

TAB FALL 2020 Book Recommendations

South Pasadena Public Library Teen Advisory Board Recommends This List was Compiled by the Fall 2020 Teen Advisory Board Members Classics The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie; art by Ellen Forney The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum The Boy in the Striped Pajamas by John Boyne Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier Lord of the Flies by William Golding The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton Brave New World by Aldous Huxley A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee 1984 by George Orwell Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck Charlotte's Web by E.B. White Realistic – YA A Study in Charlotte by Brittany Cavallaro The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky An Abundance of Katherines by John Green The Fault in Our Stars by John Green Looking for Alaska by John Green Paper Towns by John Green Turtles All the Way Down by John Green One of Us is Lying by Karen M. McManus Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell Dear Martin by Nic Stone Sadie by Courtney Summers The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas Books to Film Call Me By Your Name by Andrë Aciman Little Women by Louisa May Alcott Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. -

Chaos Walking Patrick Ness TWICE CARNEGIE WINNER

WALKER BOOKS DISCUSSION GUIDE THE NOVELS BEHIND THE MAJOR MOTION PICTURE patricknessbooks • www.patrickness.com Walker Books Discussion Guide NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE Chaos Walking Patrick Ness TWICE CARNEGIE WINNER The first book in the CHAOS WALKING series Winner of the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize “I look at the knife again, sitting there on the moss like a thing without properties, a thing made of metal as separate from a boy as can be, a thing which casts all blame from itself to the boy who uses it.” ABOUT THE BOOK Todd Hewitt is the only boy in a town of men. Ever since the settlers were infected with the Noise germ, Todd can hear everything the men think, and they hear everything he thinks. Todd is just a month away from becoming a man, but in the midst of the cacophony, he knows that the town is hiding something from him – something so awful that Todd is forced to flee with only his dog, whose simple, loyal voice he hears as well. With hostile men from the town in pursuit, the two stumble upon a strange and eerily silent creature: a girl. Who is she? Why wasn’t she killed by the germ like all the females on New World? Propelled by Todd’s gritty narration, readers are in for a white-knuckle journey in which a boy on the cusp of manhood must unlearn everything he knows in order to figure out who he truly is. 9781406385397 • £7.99 • Paperback • eBook available DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Patrick Ness chose to write Todd’s voice in the vernac- 2. -

The First Book in the Chaos Walking SERIES

Candlewick Press Discussion Guide The first book in The Chaos Walking SERIES I look at the knife again, sitting there on the moss like a thing without properties, a thing made of metal as sepa- rate from a boy as can be, a thing which casts all blame from itself to the boy who uses it. ABOUT THE BOOK Todd Hewitt is the only boy in a town of men. Ever since the settlers were infected with the Noise germ, Todd can hear every- thing the men think, and they hear everything he thinks. Todd is just a month away from becoming a man, but in the midst of the cacophony, he knows that the town is hiding something from him—something so awful that Todd is forced to flee with only his dog, whose simple, loyal voice he hears as well. With hostile men from the town in pursuit, the two stumble upon a strange and eerily silent creature: a girl. Who is she? Why wasn’t she killed by the germ like all the females on New World? Propelled by Todd’s gritty narration, readers are in for a white-knuckle journey in which a boy on the cusp of manhood must unlearn everything he knows in order to figure out who he truly is. HC: 978-0-7636-3931-0 • PB: 978-0-7636-4576-2 E-book: 978-0-7636-5216-6 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Patrick Ness chose to write Todd’s voice in the vernac- 2. Think about the title of the book: The Knife of Never ular, as Todd actually speaks, with grammatical and Letting Go. -

Audio Books 2020-2021

AUDIO BOOKS 2020-2021 With thanks to King Alfred’s Academy, Oxford for supplying the original list which we have adapted to suit our own student’s needs. Written for children KS2/3 Boy Underwater* by Adam Baron (narrated by Rafe Spall, 4 hours 40 minutes) The Storm Keeper’s Island* by Catherine Doyle (narrated by Patrick Moy, 6 hours 43 minutes) The Bone Sparrow* by Zana Fraillon (narrated by Gareth Locke, 4 hours 27 minutes) The Graveyard Book* by Neil Gaiman (narrated by Neil Gaiman); Coraline* by Neil Gaiman (narrated by Dawn French, 3 hours 34 minutes); American Gods by Neil Gaiman (narrated by Gaiman, Boutskiaris, Oreskes, McLarty, Jones, 19 hours 36 minutes – adult listeners) I Know What You Did Last Wednesday* by Anthony Horowitz (narrated by Nickolas Grace, 1 hour 37 minutes) Skulduggery Pleasant* by Derek Landy (narrated by Rupert Degas, 7 hours 9 minutes) Scarlet Ibis* by Gill Lewis (narrated by Pippa Bennet-Warner, 3 hours 53 minutes) Stop the Train* and Pull Out All the Stops* by Geraldine McCaughrean (not available on Audible but Stop the Train, our all time family favourite listen, is on Epic! and elsewhere) Wonder* by RJ Palacio (narrated by Kate Rudd, Nick Podehl, Diana Steele, 8 hours 5 minutes) Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone* by JK Rowling (narrated by Stephen Fry, 9 hours 33 minutes) + the rest of the Harry Potter series, all narrated Stephen Fry. Mississippi Bridge* by Mildred D Taylor (narrated by Danny Gerard, 53 minutes) Higher Institute of Villainous Education by Mark Walden (narrated by Jack Davenport, -

Carnegie Medal Winning Books

Carnegie Medal Winning Books 2020 Anthony McGowan, Lark, Barrington Stoke 2019 Elizabeth Acevedo, The Poet X, Electric Monkey 2018 Geraldine McCaughrean, Where the World Ends, Usborne 2017 Ruta Sepetys, Salt to the Sea, Puffin 2016 Sarah Crossan, One, Bloomsbury 2015 Tanya Landman, Buffalo Soldier, Walker Books 2014 Kevin Brooks, The Bunker Diary, Puffin Books 2013 Sally Gardner, Maggot Moon, Hot Key Books 2012 Patrick Ness, A Monster Calls, Walker Books 2011 Patrick Ness, Monsters of Men, Walker Books 2010 Neil Gaiman, The Graveyard Book, Bloomsbury 2009 Siobhan Dowd, Bog Child, David Fickling Books 2008 Philip Reeve, Here Lies Arthur, Scholastic 2007 Meg Rosoff, Just in Case, Penguin 2005 Mal Peet, Tamar, Walker Books 2004 Frank Cottrell Boyce, Millions, Macmillan 2003 Jennifer Donnelly, A Gathering Light, Bloomsbury Children’s Books 2002 Sharon Creech, Ruby Holler, Bloomsbury Children’s Books 2001 Terry Pratchett, The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, Doubleday 2000 Beverly Naidoo, The Other Side of Truth, Puffin 1999 Aidan Chambers, Postcards from No Man’s Land, Bodley Head 1998 David Almond, Skellig, Hodder Children’s Books 1997 Tim Bowler, River Boy, OUP 1996 Melvin Burgess, Junk, Anderson Press 1995 Philip Pullman, His Dark Materials: Book 1 Northern Lights, Scholastic 1994 Theresa Breslin, Whispers in the Graveyard, Methuen 1993 Robert Swindells, Stone Cold, H Hamilton 1992 Anne Fine, Flour Babies, H Hamilton 1991 Berlie Doherty, Dear Nobody, H Hamilton 1990 Gillian Cross, Wolf, OUP 1989 Anne Fine, Goggle-eyes, H Hamilton -

Award-‐Winning Literature

Award-winning literature The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and young adult literature. The Man Booker Prize for Fiction is a literary prize awarded each year for the best original full-length novel, written in the English language, by a citizen of the Commonwealth of Nations, Ireland, or Zimbabwe. The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English". The Carnegie Medal in Literature, or simply Carnegie Medal, is a British literary award that annually recognizes one outstanding new book for children or young adults. The Michael L. Printz Award is an American Library Association literary award that annually recognizes the "best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit". The Guardian Children's Fiction Prize or Guardian Award is a literary award that annually recognizes one fiction book, written for children by a British or Commonwealth author, published in the United Kingdom during the preceding year. FICTION Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley, Michael L. Printz Winner 2012 A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, Pulitzer Prize 2011 Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, National Book Award 2011 The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, Man Booker Prize 2011 Ship Breaker by Paolo Baciagalupi, Michael -

Download a Discussion Guide

THE KNIFE OF NEVER LETTING GO The Novel Behind the Chaos Walking Movie BY PATRICK NESS READERS’ GUIDE 1. How does Todd’s voice, including his grammar and spelling, reflect his environment and upbringing? 2. Reading and writing aren’t allowed in Prentisstown. How is Todd’s journey affected by his lack of education? 3. How does the denial of education allow totalitarian governments, like that in Prentisstown, to control their citizens? 4. Why do you think Noise is indicated with a different font? 5. Dystopian novels—ones that describe a future that is dark and often fearful—give the author a chance to comment on present-day society. How does Noise translate into our current lives? Where do you see Noise in the present day? What positive and negative impact does Noise have on our lives? 6. How do Todd’s actions against the Spackle change him? How do they change Viola’s feelings about him? Do they change your feelings about Todd? 7. Think about Patrick Ness’s use of gender roles in the novel. How are they similar to and different from contemporary gender roles? How does Viola change Todd’s views of women and their roles in his society? 8. Hope is an important topic in the last hundred pages of the book. Todd and Viola’s hope rests in Haven. Do they find what they had hoped to at the end of the road? 9. The men in the novel can hear one another’s thoughts via Noise, but do they really know one another? Even though Todd can’t hear Viola’s Noise, he discovers that he can read her thoughts and feelings anyhow. -

Science Fiction Book List

Science fiction is a genre that can never run out of exciting reading material, as there are countless things that can happen in these types of stories. There’s amazing worlds waiting to be explored, deadly global threats to prevent, weird alien races to meet, and so much more. The Learning Curve have chosen a selection of books to review, these are available from the library, and can be borrowed once lockdown has finished. There’s a whole universe to explore in our library shelves…… Tales of Science Fiction: The Standoff By John Carpenter At Tattersall Prison, a max-lock for the baddest of the bad, sleepless nights are the norm… until a fireball from the sky turns the night shift into a nightmare ― trapping guards and cons on the inside, cops on the outside, and escapees in-between… all of them threatened by a hideous alien invader which needs nice, warm human bodies in which to incubate. From the outside, it looks like a replay of Waco, but from the inside, it’s more like Dante’s first draft of the Inferno. Psychotic Fraiser Bonner leads an army of convicts with a grudge against lead guard Wayne Jessup, whose crew is marooned inside with no means of exit. Black ops spook Elaine Farris tries to call the shots as captive guards get executed by Bonner. Farris dreads the moment she will have to call in her “expert,” Conrad Gant, whose life she destroyed six years earlier. Why? Because Gant knows about the alien interlopers, who use the human form as a chrysalis and shed the envelope of flesh to produce Earth- compatible conquerors… and Gant was hounded into silence by Elaine and her fixers.