Striking Fear in the Circuits: the Electric Feminine Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALLA Press Release May 26 2015 FINAL

! ! ! A$AP ROCKY’S NEW ALBUM AT.LONG.LAST.A$AP AVAILABLE NOW ON A$AP WORLDWIDE/POLO GROUNDS MUSIC/RCA RECORDS TRENDING NO. 1 ON ITUNES IN THE US, UK, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, FRANCE, GERMANY AND MORE SOPHOMORE ALBUM FEATURES APPEARANCES BY KANYE WEST, LIL WAYNE, ScHOOLBOY Q, MIGUEL, ROD STEWART, MARK RONSON, MOS DEF, JUICY J, JOE FOX AND OTHERS [New York, NY – May 26, 2015] A$AP Rocky released his highly anticipated new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, today (5/26) due to the album leaking a week prior to its scheduled June 2nd release date. The album is currently No. 1 at iTunes in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Russia and more. The follow-up to the charismatic Harlem MC’s 2013 release, Long.Live.A$AP, A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, features a stellar line up of guest appearances by Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson on “Everyday,” ScHoolboy Q on “Electric Body,” Lil Wayne on a new version of the previously released “M’$,” Kanye West and Joe Fox on “Jukebox Joints,” plus Mos Def, Juicy J, UGK and more on other standout tracks. Producers Danger Mouse, Jim Jonsin, Juicy J and Mark Ronson among others, contributes to the album’s trippy new sound. Executive Producers include Danger Mouse, A$AP Yams and A$AP Rocky with Co-Executive Producers Hector Delgado, Juicy J, Chace Johnson, Bryan Leach and AWGE. In 2013, A$AP Rocky announced his global arrival in a major way with his chart- topping debut album LONG.LIVE.A$AP. -

MARRIAGE OR CAREER? DOMESTIC IDEOLOGY in GEORGE GISSING's the ODD WOMEN by KUO-WEI HSU Presented to the Faculty of the Gradua

MARRIAGE OR CAREER? DOMESTIC IDEOLOGY IN GEORGE GISSING’S THE ODD WOMEN by KUO -WEI HSU Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ART S IN ENGLIGH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, to Dr. Martin Danahay, my thesis advisor, goes my deepest gratitude for his conscientious directing and correction on my thesis. Without his insightful instruction, this thesis would be laden with flaws. Next, I am also indebted to Dr. Jacqueline Stodnick and Dr. Kevin Gustafson, whose valuable suggestions improve the reading of this thesis. Besides, I would like to thank my parents for their financial assistance so that I can pursue my studies without being troubled by monetary matters. In addition, I am very grateful to my sister who generously gives her warm care for me while I stay at her place to refresh myself from academic studies. Finally, I thank all my friends for their kind support and concern for me when I was in difficulties. Without their help, this thesis could not come into being. May 2, 2005 ii ABSTRACT MARRIAGE OR CAREER? DOMESTIC IDEOLOGY IN GEORGE GISSING’S THE ODD WOMEN Publication No . ______ Kuo-wei Hsu, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2005 Supervising Professor: Martin Danahay Although George Gissing is acclaimed for his progressive thoughts on liberating women from patriarchy by establishing financial independence, s ome critics challenge such praise for Gissing by arguing that he is still confined within patriarchal thinking because he still adheres to domestic ideology, which advocates that women should stay within the domestic sphere and be protected from co rruption of the outside world. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 26, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 November Booknews 2014 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Happy holidays to all…and remember, a book is a present you can open again and again…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. TUESDAY DECEMBER 2 7:00 PM SUNDAY DECEMBER 14 12:00 PM Gini Koch signs Universal Alien (Daw $7.99) 10th in series Amy K. Nichols signs Now That You’re Here: Duplexity Part I WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 3 7:00 PM (Random $16.99) Ages 12+ Lisa Scottoline signs Betrayed (St Martins $27.99) Rosato & THURSDAY DECEMBER 18 7:00 PM Christmas Party Associates Hardboiled Crime discusses Cormac McCarthy’s No Country SATURDAY DECEMBER 6 10:30 AM for Old Men ($15) Coffee and Crime discusses Christmas at the Mysterious Book- CLOSED FOR CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S DAY shop ($15.95) SATURDAY DECEMBER 27 2:00 PM MONDAY DECEMBER 9 7:00 PM David Freed signs Voodoo Ridge (Permanent Press $29) Cordell Bob Boze Bell signs The 66 Kid; Raised on the Mother Road Logan #3 (Voyageur Press $30) Growing up on Route 66. Don’t overlook THURSDAY JANUARY 8 7:00 PM the famous La Posada Hotel’s Turquoise Room Cookbook ($40), Charles Todd signs A Fine Summer’s Day (Morrow $26.99) Ian Signed by Chef Sharpe, flourishing today on the Mother Road Rutledge TUESDAY DECEMBER 10 7:30 PM FRIDAY JANUARY 9 7:00 PM Thrillers! EJ Copperman signs Inspector Specter: Haunted Guesthouse Matt Lewis signs Endgame ($19.99 trade paperback) Debut Mystery #6 (Berkley ($7.99) thriller FRIDAY DECEMBER 12 5:00-8:00 PM 25th Anniversary Party Brad Taylor signs No Fortunate Son (Dutton $26.95) Pike Logan The cash registers will be closed. -

Talented ASAP Rocky Stuck in a Rut

"ALLA" Album Review: Talented ASAP Rocky Stuck In A Rut Author : gwgras Coming out of Harlem, New York is Asap Rocky. His road to hip hop stardom isn’t anything new: from a poor family, dealt drugs, saw death at an early age–began rapping–things happened. That’s not to belittle his journey – at all, but one wouldn’t get that “defeated while coming up” tone if they listened to Rocky’s music. Some would call him more of a modern-day hippie–much like Wiz Khalifa and others. He struck a $3 million dollar deal because of his mixtape success and has capitalized releasing hits like “F’n Problems” and “Wild For the Night” from his first album “Long. Live. ASAP.” His follow up album “ALLA (At Long Last ASAP)” comes with the pressure of capitalizing off his commercial success. The album starts off perfectly with “Holy Ghost.” In terms of delivery and tone, Rocky sounds more like T.I. than anything else, but delivers some insightful lines: “Satan giving out deals, finna own these rappers / the game is full of slaves and they mostly rappers / you sold your soul first, then your homies after / Let’s show these stupid field n*****s they can own they masters.” Rocky is a young business mind and finds it weird how some who have been in the game longer than him still get screwed over with music industry politics. The laid back “Excuse Me” shows Rocky delivering a laid back flow in which he rattles off a perfect rhyme scheme. -

Introduction 1 the Good Mother

Notes Introduction 1. By ‘motherhood’ I am referring to the character of the mother and the practice of motherhood on screen. By the ‘maternal’ I am referring to the characteristics and symbolism which evoke motherhood. 2. This is not to suggest that the figure of the mother is entirely absent from pre-1960s cinema, rather that a range of socio-economic factors led to a development in the horror genre. For the purposes of clarity I wish to focus on post-Classical horror cinema. 3. This is not to suggest that no debates about motherhood existed prior to this, rather that discussions of the mother in film increased greatly after these years. 4. The woman’s film centres on a female protagonist, deals with specifically ‘female’ issues (such as motherhood or domesticity) and is aimed at a female audience. For Doane, the maternal melodrama is a sub-category of the woman’s film. While the maternal melodrama is more readily asso- ciated with films of the Classical Hollywood period, it remains a popular sub-genre of modern mainstream cinema. The maternal melodrama, as the name suggests, deals with the figure of the mother and the impact of motherhood on her life or that of the child. 5. This is not to suggest that discussion of the mother/maternal is limited to these genres, simply that they seem to have provoked the most interest. 6. For example, see Alien and the various studies by Creed, Bundtzen or Rosemary’s Baby as discussed by Fischer or Kuhn. 7. See Mulvey (2000); De Lauretis, Teresa, Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Chase by K.R. Dwyer Chase (Novel) Chase Is Dean Koontz's First Hardcover Novel, Originally Written Under the Name K

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Chase by K.R. Dwyer Chase (novel) Chase is Dean Koontz's first hardcover novel, originally written under the name K. R. Dwyer and released in 1972, it was revised and reissued in 1995 within Strange Highways . Contents. Plot summary Reception References. Plot summary. Chase is the story about Benjamin Chase. "Benjamin Chase is a retired war hero living in an attic apartment. He is struggling with a drinking habit. One night he rescues a young woman from an obsessed killer. As a result, the killer has changed his target to Chase. He begins phoning Chase and warning that he is out for revenge. The killer, simply named "The Judge" is threatening to kill Chase but the police don't believe him as he has a history of alcohol-related incidents. Chase is forced to take matters into his own hands and attempts to unmask The Judge himself and end the threat of a vengeful lunatic." Reception. In reviewing Chase as a part of Strange Highways, Kirkus Reviews said the book was mostly thrilling [1] while the Orlando Sentinel panned the novel. [2] Related Research Articles. Dean Ray Koontz is an American author. His novels are billed as suspense thrillers, but frequently incorporate elements of horror, fantasy, science fiction, mystery, and satire. Many of his books have appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list , with 14 hardcovers and 16 paperbacks reaching the number-one position. Koontz wrote under a number of pen names earlier in his career, including "David Axton", "Deanna Dwyer", "K.R. -

HEAL Hosts Caltech's First Beaver 5K Run/Walk

The California Tech Volume CXViii number 29 Pasadena, California [email protected] June 1, 2015 HEAL hosts Caltech’s first Beaver 5K Run/Walk STEPHANIE HUARD with Caltech’s health educator, Contributing Writer Jenny Mahlum, to educate the community on matters pertaining It was a warm and exciting to overall health and Caltech- morning on Saturday, May 30, specific resources for maintaining when over 170 runners gathered a healthy lifestyle. Within HEAL, on Beckman Lawn for Caltech’s there are five subcommittees: first Beaver 5K Run/Walk. The Nutrition and Fitness, Mental participants, including members of Health Awareness, Stress and the faculty, staff, postdoc, graduate Sleep, Sexual Health and Healthy and undergraduate communities, Relationships, and Drugs and lined up at 10:30 a.m. near Broad Alcohol. The CCA is group of Center, and made their way twice community volunteers from the through a twisty-turny loop on Catalina Apartments that plan campus to reach 3.1 miles. events and act as representatives Over the course of the race, for the Catalina community. The volunteers were stationed CCA consists mostly of graduate around the course to provide students. encouragement to participants, HEAL and the CCA thank and to provide assistance in everyone who participated in the the event of injury or any other event for making it a success. Runners line up at the start by Broad Center. emergency. At the end of the race, the fastest woman and man in the undergraduate, graduate and faculty/staff/postdoc categories received a prize of a Jamba Juice gift card, and the fastest team and biggest team received trophies. -

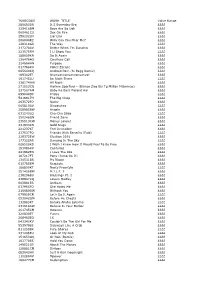

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Egrove June 2, 2015

University of Mississippi eGrove Daily Mississippian Journalism and New Media, School of 6-2-2015 June 2, 2015 The Daily Mississippian Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline Recommended Citation The Daily Mississippian, "June 2, 2015" (2015). Daily Mississippian. 1169. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline/1169 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and New Media, School of at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Daily Mississippian by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuesday, June 2, 2015 THE DAILY Volume 103, No. 130 THE STUDENTMISSISSIPPIAN NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI SERVING OLE MISS AND OXFORD SINCE 1911 Visit theDMonline.com @thedm_news news lifestyles sports Groups aid A$AP Rocky: the Track team transfer hustle continues travels to NCAA students on championship campus in Oregon Page 4 Page 6 Page 8 Ole Miss’ Texans affected by flood Faculty chair drive honors chancellor CLARA TURNAGE be broad-based,” Weakley [email protected] said. “It will allow the pro- vost to use it for the highest Across campus faculty, and best need of the univer- staff and alumni are working sity. It could go many differ- to host a $1.5 million faculty ent schools over its lifetime. chair drive in honor of Chan- Whatever the greatest need cellor Dan Jones. is.” The drive, announced on The funds could go into ef- May 15, only has 16 days left, fect as early as this August de- but Wendell Weakley, presi- pending on the results of the dent and CEO of the Universi- drive, he said. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

KOONTZ, Dean R(Ay)

KOONTZ, Dean R (ay) Geboren: Everett, Pennsylvania, USA, 9 juli 1945 Pseudoniemen: David Axton; Brian Coffey, Deanna Dwyer; K.R. Dwyer; John Hill; Leigh Nichols; Anthony North; Richard Paige; Owen West Opleiding: Shippensburg State College, Pennsylvania, B.A. engels, 1966 Carrière: werkte bij een federaal armoede-bestrijdings programma, 1966-1967; leraar engels op een high school, 1967-1969; full-time schrijver sedert 1969. Familie: getrouwd met Gerda Ann Cerra, 1966 Woont in Orange, Californië. (foto: Fantastic Fiction) Detective: Michael Tucker (o.ps. Brian Coffey) detective: Odd Thomas kan de doden zien en ziet in zijn dromen wat mensen te wachten staat. Odd Thomas: 1. Odd Thomas 2003 De gave 2004 Luitingh ook verschenen als filmeditie odt: Odd Tomas: De gave 2015 Luitingh 2. Forever Odd 2005 De vriendschap 2006 Luitingh 3. Brother Odd 2006 De broeder 2007 Luitingh 4. Odd Hours 2008 De ziener 2008 Luitingh 5. Odd Apocalypse 2012 De miljardair 2012 Luitingh 6. Deeply Odd 2013 De lifter 2013 Luitingh~Sijthoff 7. Saint Odd 2015 graphic novels: In Odd We Trust #12 2008 Odd Is on Our Side #13 2010 House of Odd #14 2012 novellas: 1. Odd Interlude Part One 2012 2. Odd Interlude Part Two 2012 3. Odd Interlude Part Three 2012 4. Odd Interlude 2012 Het motel 2013 Luitingh~Sijthoff omslag ondertitel: A Special Odd Thomas Adventure 5. You Are Destined to Be Together Forever 2014 omnibus: The Complete Thomas Odd Series 2016 bevat: Odd Thomas Forever Odd Brother Odd Odd Hours Odd Apocalypse Odd Interlude Deeply Odd Saint Odd andere crimetitels: -

Mr. Helts Haircut by Emma Stevens

inside this issue By: Sami Strack Sports 2 The glow run was held on November 5th. 164 people attended the Meet the Students 35 run. Mr. Helt and Mrs. Burns took a wrong turn, a common problem among this year's runners. Because of this, Mr. Helt got his head shaved, and Mrs. Burns Teacher of the Month 6 got a pie in the face. Amanda Williams, Brandon Myers mom, won the “Most glow” competition. It seemed like everyone had fun and it was great exercise. Animals 7 Plants and Animals 8 Games and Electronics 910 Veterans Day 11 Movies and Music 1213 CrossWord/Horoscopes 14 Editor’s Note If you find any errors in the Heat Wave that the staff missed point it out to Mr. Harris if no one else has found it you will receive 1 heat buck! Mr. Helts Haircut By Emma Stevens This weekend our school had a Glow Run. Before the run,we had a two teachers make some wagers. We had Mrs Burns,our principal say that she would take pie to the face.And Mr Helt,the 8th grade science teacher said that he would shave his head. So they kept their word and when the Glow Run came around and they still had their deals. But during the run they both took a wrong turn and disqualified themselves. Because they thought it was fair. So on Monday November 9th Mr Helt was shaved bald his morning, Mrs. Burns was supposed to get her pie in the face,but she had a meeting.