<I>Lunar Park</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Lil Uzi Songs Download

Lil uzi songs download Continue Source:4,source_id:870864.object_type:4, id:870864,status:0,title:LIL U ULTRASOUND VERT,share_url:/artist/lil-uzi-vert,albumartwork: objtype:4 Thank you for showing interest in '. It is only available in India. Click here to go to the homepage or you'll be automatically redirected within 10 seconds. setTimeout (function) $'.'.artistDetailPage.artistAbout'). Download music from your favorite artists for free with Mdundo. Mdundo started in collaboration with some of Africa's best artists. By downloading music from Mdundo YOU to become part of the support of African artists!!! Mdundo is financially supported by 88mph - in partnership with Google for Entrepreneurs. Mdundo kicks the music into the stratosphere, taking the artist's side. Other mobile music services hold 85-90% of sales. What ?!, Yes, most of the money is in the pockets of major telecommunications companies. Mdundo lets you track your fans and we share any revenue earned from the site fairly with the artists. I'm a musician! - Log in or sign up for hip-hop August 2, 202015 September 2020 Olami Published in Hip Hop, TrendingTagged Future, Lil Uzi Vert1 Best Rap Song 2019Featuring Lil Uzi Vert, Doja Cat, and Young Thug, along with many exciting young upstarts 20 Best Rap Albums 2017 From Playboi Carti's muttering opus Vince Staples' delirium up deconstructed fame, is the most important rap record of the year. The 100 best songs of 2017 from Lord's ecstatic emotional purification to Frank Ocean's ode to cycling to the frantic knock of Cardi B, this is our pick for the best songs of the year. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

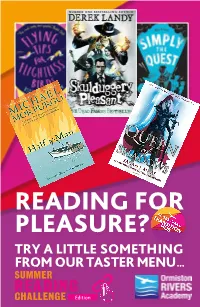

Reading for Pleasure? Try a Little Something from Our Taster Menu

READING FOR PLEASURE? TRY A LITTLE SOMETHING FROM OUR TASTER MENU... Edition Looking for something to read but don’t know where to begin? Dip into these pages and see if something doesn’t strike a spark. With over thirty titles (many of which come recommended by the organisers of World Book Day - including a number of best sellers), there is bound to be something to appeal to every taste. There is a handy, interactive contents page to help you navigate to any title that takes your fancy. Feeling adventurous? Take a lucky dip and see what gems you find. Cant find anything here? Any Google search for book extracts will provide lots of useful websites. This is a good one for starters: https://www. penguinrandomhouse.ca/books If you find a book you like, there are plenty of ways to access the full novel. Try some of the services listed below: Chargeable services Amazon Kindle is the obvious choice if you want to purchase a book for keeps. You can get the app for both Apple and Android phones and will be able to buy and download any book you find here. If you would rather rent your books, library style, SCRIBD is the best app to use. They charge £8.99 per month but you can get the first 30 days free and cancel at any time. If you fancy listening to your favourite stories being read to you by talented voice recording artists and actors, tryAudible : they offer both one off purchases and subscription packages. Free services ORA provides access to myON and you will have already been given details for how to log in. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Bret Easton Ellis Is Vernon Downs

1 Bret Easton Ellis is Vernon Downs MAY 23, 2014 BY JAIME CLARKE – FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE GOOD MEN PROJECT Vernon Downs is the story of Charlie Martens, who is desperate for stability in an otherwise peripatetic life. An explosion that killed his parents when he was young robbed him of normalcy. Ever the outcast, Charlie recognizes in Olivia, an international student from London, the sense of otherness he feels and their relationship seems to promise salvation. But when Olivia abandons him, his desperate mind fixates on her favorite writer, Vernon Downs, who becomes an emblem for reunion with Olivia. ♦◊♦ By virtue of the fact that Vernon Downs is a roman a clef, which is French for “novel with a key,” there is a small measure of fact mixed in with the fictional world and characters of the novel. The titular character is obviously based on the writer Bret Easton Ellis, but there are other allusions as well. So herewith, a page by page key to Vernon Downs : Pg 3: “Summit Terrace” is an allusion to Summit Avenue, the birthplace of F. Scott Fitzgerald in St. Paul, MN Pg 4: “Shelleyan” is named for a band I loved in college, Shelleyan Orphan Pg 4: “Minus Numbers” was the title Bret Easton Ellis’s advisor at Bennington College, Joe McGinnis, wanted to give Less Than Zero Pg 5: The story about the Batman skit is borrowed from my past 2 Pg 6: “Southwest Peterbilt” was my father’s employer in Phoenix, AZ for many years Pg 6: The story about the boyfriend who killed the ex-husband is borrowed from my past. -

Reading the Body in Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho (1991): Confusing Signs and Signifiers

Reading the Body in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) David Roche To cite this version: David Roche. Reading the Body in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991): Confusing Signs and Signifiers. Groupe de Recherches Anglo-Américaines de Tours, Groupe de recherches anglo-américaines de Tours, Université de Tours, 1984-2008, 2009, 5 (1), pp.124-38. halshs-00451731 HAL Id: halshs-00451731 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00451731 Submitted on 6 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 124 GRAAT On-Line issue #5.1 October 2009 Reading the Body in Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho (1991): Confusing Signs and Signifiers David Roche Université de Bourgogne In Ellis’s scandalous end-of-the-eighties novel American Psycho , the tale of Patrick Bateman—a Wall Street yuppie who claims to be a part-time psychopath— the body is first conceived of as a visible surface which must conform to the norms of the yuppies’ etiquette. I use the word “etiquette,” which Patrick uses (231) and which I oppose to the word “ethics” which suggests moral depth, to stretch how superficial the yuppie’s concerns are and to underline, notably, that the yuppie’s sense of self is limited to his social self, his public appearance, his self-image, which I relate to D. -

Zoo Alicia Cotsoradis Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 4-2018 Zoo Alicia Cotsoradis DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Cotsoradis, Alicia, "Zoo" (2018). Student research. 82. https://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/82 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zoo: By Alicia Cotsoradis DePauw University Honor Scholar Program Class of 2018 Sponsor: Ronald Dye Committee: Rebecca Bordt, Jeffrey McCall, Robert Stevens 1 Table of Contents The Beginning………………………………..3 Sister………………………………………...12 School………………………………………..20 Crime………………………………………..22 First Stint in Prison………………………..29 Prison Take Two…………………………...32 Zoo………………………………………….....38 Admissions……………………………………...40 Black, and Brown, and Polar Beasts, Oh My….47 Parrots…………………………………………..53 Intake………………………………………...…..60 The Jumbo Beasts……………………………..67 Picture Day……………………………………..74 The Aftermath……………………………………..81 The Petting Zoo…………………………………..86 Worker Beasts………………………………..93 Big Game Hunting Safari…………………………..103 The Grand Escape……………...……………114 On the News…………………………………..120 The End…………………...……………….120 Goodbye…………………………….……...130 2 The Beginning My name is Ray, but my name won’t matter once you see my face. You see, I’m scary. I’m the monster that hides in your kid’s closet at night, just waiting to pop out and yell boo. I’m danger, and not the sexy kind. You know, the devilish looking man who rides up on a motorcycle only to whisk you off your feet, then leaves you choking on your own breath. -

Bret Easton Ellis's Glamorama and Jay Mcinerney's Model

Fashion Glamor and Mass-Mediated Reality: Bret Easton Ellis’s Glamorama and Jay McInerney’s Model Behaviour By Sofia Ouzounoglou A Dissertation to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki November 2013 i TABLE of CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................iii INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE: Reconstructing Reality in Bret Easton Ellis’s Glamorama (1998) 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..15 1.1 “Victor Who?”: Image Re-enactment and the Media Manipulation of the Self……..19 1.2 Reading a Novel Or Watching a Movie?.....................................................................39 CHAPTER TWO: Revisiting Reality in Jay McInerney’s Model Behaviour (1998) 2. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..53 2.1 Media Dominance and Youth Entrapment…………………………………………...57 2.2 Inset Scenarios and Media Constructedness……………………………………........70 EPILOGUE………………………………………………………………………………...........80 WORKS CITED………………………………………………………………………………...91 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE……………………………………………………………………....94 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This M.A. thesis has been an interesting challenge as I set off -

Unreliable Narration in Bret Easton Ellisâ•Ž American Psycho

Current Narratives Volume 1 Issue 1 Narrative Inquiry: Breathing Life into Article 6 Talk, Text and the Visual January 2009 Unreliable narration in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho: Interaction between narrative form and thematic content Jennifer Phillips University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/currentnarratives Recommended Citation Phillips, Jennifer, Unreliable narration in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho: Interaction between narrative form and thematic content, Current Narratives, 1, 2009, 60-68. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/currentnarratives/vol1/iss1/6 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Unreliable narration in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho: Interaction between narrative form and thematic content Abstract In this paper I analyse the narrative technique of unreliable narration in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho (1991). Critics have been split about the reliability of Patrick Bateman, the novel’s gruesome narrator- protagonist. Using a new model for the detection of unreliable narration, I show that textual signs indicate that Patrick Bateman can be interpreted as an unreliable narrator. This paper reconciles two critical debates: (1) the aforementioned debate surrounding American Psycho, and (2) the debate surrounding the concept of unreliable narration itself. I show that my new model provides a solution to the weaknesses which have been identified in the rhetorical and cognitive models previously used to detect unreliable narration. Specifically, this new model reconciles the problematic reliance on the implied author in the rhetorical model, and the inconsistency of textual signs which is a weakness of the cognitive approach. -

James Pitts – 1

File 1-1 0:00:00.0 Then he asked me later on, two, three, four years after that, he mentioned it again. I asked him, I said, “Are you sure that’s what you want?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, I ain’t makin’ a promise that I might not be able to keep, but I’ll put some stipulations in it, a possibility.” I said— 0:00:20.8 End file 1-1. File 1-2 0:00:00.0 —and I finished ninth grade at Stringtown [?]. Well, I said I finished it. I went. At the end of the school year I got an award for being an occasional ___ student. So the next year I quit. I had to put in the crops, and I stayed there about two years, and I went to my granddad’s. ‘Cause we walked miles one way to catch the—little over three miles, ‘bout three and a quarter miles to catch the bus and had to be there about 10 minutes to 7 in the mornin’ and then ride it several miles into school. And had three different creeks to cross, and they didn’t have bridges over ‘em, and sometimes that was ___, and sometimes I just didn’t want to go. So anyway, then I went back and I started in the tenth, and I never did go pick up my grades or report cards, so I don’t even know if I passed the ninth or not. But anyway— (What year was that?) 0:01:03.8 That’s—I have a great memory. -

There Is an Idea of a Patrick Bateman, Some Kind of Abstraction, but There

1 “…there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.” Bret Easton Ellis, author of the controversial book American Psycho (1991) puts forward the thought that mind and body are distinct. The quote I shall be discussing is one of the protagonists’ (Patrick Bateman’s) key self-analysis, in which he believes that even though he physically exists, he is nothing more than an illusion and an abstraction. Bateman’s feelings of absence are reinforced by his numerous internal monologues, this quote being one of them. I will use Rene Descartes’ meditations along with the concept of the self in order to differentiate between mind and body, and to conclude whether Bateman is really not there. Firstly I will look at the concept of the self. Self-analysis is the first step to understand who you are, and self-conceptualization is a cognitive component of oneself. Once one is fully aware of oneself, that person then has a concept of himself/herself. This concept is usually broken down into two parts: The Existential Self and The Categorical Self. The existential self is the sense we get of being different from those around us, and the realization of the constancy of the self. The categorical self is when one realizes that he or she is distinct as well as an object in this world, thus having properties that may be experienced, just like any other object.