Ahmedabad: Town Planning Schemes for Equitable Development—Glass Half Full Or Half Empty?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

CASE 1 GREATER THAN PARTS GREATER THAN PARTS THAN PARTS GREATER Ahmedabad, India Public Disclosure Authorized Scaling Up with Contiguous Replication of Town Planning Schemes A Metropolitan Opportunity Madhu Bharti and Shagun Mehrotra Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Editors Shagun Mehrotra, Lincoln Lewis, Mariana Orloff, and Beth Olberding © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contri- butions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, itsBoard of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Un- der the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. -

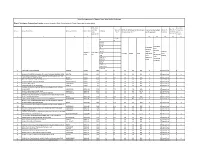

NAME of the ACCOUNT ADDRESS Amount of Subsidy

Bank of India Actual disbursement of subsidy to Units will be done by banks after fulfillment of stipulated terms & conditions Date of issue 09-10-2014 vide sanction order No. 22/CLTUC/RF-6/BOI/13-14 (Amt. in Lakh) Amount of subsidy NAME OF THE ACCOUNT ADDRESS claimed 1 GHANSHYAM PLASTIC INDUSTRIES PLOT NO. 3, MORBI ROAD, HALVAD - 363330 6.75 2 VERSATILE ALUCAST PVT.LTD. PLOT NO.A-8/2, MIDC SHIROLI, TAL. HATKANGALE, DIST: KOLHAPUR 15 3 SHRI TIRUPATI RICE MILL AT. MUNDIKOTA, TIRORA, GONDIA 9.1455 4 MAA BHAVANI PACKAGING IND PLOT NO.56,57,70 & 71, GIDC ESTATE, DHANDHUKA, TAL.DHNDHUKA, AHMEDABAD 3.3045 5 LAXMI MANUFACTURERS 5, UMAKANT UDHYOG NAGAR, OPAL ESTATE, VILLAGE RAJKOT, DIST: RAJKOT 1.5375 6 AKAR ENGINEERING PLOT NO.36, 2ND FL. KRISHNA IND. ESTATE, SABARMATI, AHMADABAD 5.1 7 KAKADIYA PARESHBHAI DHIRAJBHAI 104, SARJAN IND. ESTATE, NIKOL, AHMADABAD 4.6845 8 SHREE SANJALIYA POLYMERS NO.139, SURVEY NO.129, 140/141 GIDC SHANTIDHAM, VERAVAL SHAPAR, DIST. RAJKOT, GUJARAT 5.67 9 SURESH BABULAL PATEL PLOT NO.33, KRISHNA IND. ESTATE, SABARMATI, AHMADABAD 5.1615 10 SHREE JALARAM INDUSTRIES NR.PATHIK PETROL PUMP, IDAR, DIST: SABARKANTHA, GUJARAT 4.725 11 TRINITY AUTO & AGRO INDUSTRIES SURVEY NO.63, MASVAR RD., NR. PANORAMA CHOKDI, DUNIA, HALAL, DIST: PANCHAMAHAL. 8.382 12 CITY INDUSTRIES 986/12A, DIAMOND PARK, G.I.D.C. ESTATE, MAKARPURA, VADODARA 0.9945 13 J.K. CNC PRODUCTS NO.33,3RD STREET, GANAPATHY PUDUR, GANAPATHY POST, COIMBATORE 4.8105 SURVEY NO.34, PLOT NO.16, NR. RHYNO FOAM, NH 8/B, SHAPAR (VERAVAL), TAL: KOTDA SANGANI, 14 ARYAN POLYMERS 2.9835 DIST: RAJKOT 15 OMKAR INDUSTRIES PLOT NO.146, INDUSTRIAL ESTATE PALUS, DIST: SANGLI 1.53 16 SHREE KOOLDEVI INDUSTRIES 4.0155 17 METRO RECYCLE INDS. -

Parshawanath Metro City

https://www.propertywala.com/parshawanath-metro-city-ahmedabad Parshawanath Metro City - Chandkheda, Ahme… 2, 3 & 4 BHK Flat for sale in Metro city Ahmedabad Parshawanath Metro City is an ongoing project of this group, offering 2, 3 & 4 BHK residential apartments and located at Chandkheda, North Ahmedabad. Project ID : J305808119 Builder: Parshawanath Builders Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: Parshawanath Metro City, Chandkheda, Ahmedabad (Gujarat) Completion Date: Nov, 2014 Status: Started Description Parshwanath Metro City – A scheme to elevate your luxury dreams that is Metro City. A apt gift for the city with endless dreams! Located at the quite, serene yet most progressing area of Ahmedabad. It offers 2, 3 & 4 BHK Luxurious Apartment with all aspect modern amenities and features like 24 hours water supply, Percolating well for rain water harvesting, Day & night security services by professional security guards and CCTV campus monitoring, Ample parking space for two, four wheelers, Senior citizen sit outs, Well landscaped gardens, children play area with play staton, Elegant entrance foyer for each block, provision of central pipe for domestic gas supply, etc. Type - 2, 3 & 4 BHK Luxurious Apartment Buildup Area - 1593 Sq. Ft. (175 yds.), 1602 Sq. Ft. (178 yds.), 2205 Sq. Ft. (245 yds.), 2250 Sq. Ft. (250 yds.). Price - On Request Features 24 hours water supply. Day & night security services by professional security guards and CCTV campus monitoring. Percolating well for rain water harvesting. Ample parking space for two & four wheelers. Drop off zone for school buses as well for public transport. Senior citizen sit outs. Well Landscaped gardens, children play area with play station. -

Through Development Plan & Town Planning Scheme

Land Pooling and Land Management Through Development Plan & Town Planning Scheme Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority September 2014 Contents of the Presentation Introduction First Tier Planning Process - Development Plan Second Tier Planning Process - Town Planning Scheme (Self Financing Mechanism) Town Planning Scheme Procedure - Physical Planning Town Planning Scheme Procedure - Fiscal Planning Town Planning Scheme : An Efficient and Effective Tool To Implement Development Plan Land Management Findings Introduction Urbanization in Gujarat • Third Most urbanized State with 37.35 % of Urban Population as against 27.78% of India. • 167 Urban Local Bodies • Ahmedabad is 7th largest Urban Agglomeration in India. • Third Fastest Growing Cities in the World Ahmedabad in a Regional Context • Sanand SIR • Changodar SIR. • Gandhinagar. • 5 Growth Centers. History of Town Planning • The Bombay Town Planning Act 1915: Provision of Town Planning Scheme • Bombay Town Planning Act 1954 : The Provision of Development Plan added. • Gujarat Town Planning & Urban Development Act,1976 Provision of Planning the Urban Development Area/ Authority. TPS 2 Kankaria Sanctioned DP 1965 Sanctioned DP 2011 (AUDA) Challenges to Urban Planning • Implementation of Development Plan / Master Plan • Implementation of Regional, City and Neighborhood Level Physical and Social Infrastructure • Land Bank for Urban Poor • Resource Generation and Mobilization in terms of Physical / Land • Resource Generation and Mobilization in terms of Fiscal / Finance • Improving and Maintaining -

Public-Private Partnership for Road Infrastructure Development

Public-Private Partnership for Road Infrastructure Development Until recently, city road development was considered to be in public domain with the government bearing the prime responsibility for development and maintenance of roads. Implementation of road projects and their maintenance suffered as it became solely dependent on the availability of funds from the government budget. Thus, it was important to explore alternative means of financing infrastructure projects. The Sardar Patel Ring Road in Ahmedabad demonstrates how public-private partnership (PPP) models can be used effectively for city infrastructure Documented by: development. Ahmedabad Urban Urban Management Centre (UMC) as a part of Development Authority (AUDA) has Mega Cities....Poised For Change - Leading been working with the private sector to Practices Catalogue - 2007 realize this prestigious project. AUDA has managed to implement a major part Contact: of this large scale project in a brief time Urban Management Centre, period. The case study highlights the 3rd Floor, AUDA Building, key features of the project, which are Usmanpura, Ashram Road, reflected in its financing model, land Ahmedabad - 380014 development mechanism, project management and aspects of PPP. Telefax: 079-27546403/ 5303/1599 Email: [email protected] Public-Private Partnership for Road Infrastructure Development Mega Cities...Poised for Change, Leading Practices Catalogue, 2007 SBTIituation efore he nitiative ISmplementation trategies he peripheral areas of Ahmedabad have been Conceptualizing the Ring Road expanding after 1980s. Population growth in these T The Sardar Patel (SP) Ring Road was conceptualized in areas has been more rapid than the areas within the city the Revised Development Plan of 2011 of AUDA. limits. -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population. -

Management Quality Policy

SM SPACE MANAGEMENT QUALITY POLICY Space Management is a professionally managed Real Estate Agency, availing or providing space, to individuals and corporates, for residential or commercial use, on rent or for sale / purchase, ensuring utmost customer satisfaction, by optimizing the use of technology and trained human resource. SM Building Relations in Reality SPACE MANAGEMENT Space is one of those ‘rare commodities’ that needs conscious evaluation before taking any decision. One has to manage whatever he has, or get, optimally …and sensibly. And that is precisely what Space Management is here to help you do. Moving out of Ahmedabad temporarily / permanently, and want to lease / sell your property? Just been transferred to Ahmedabad, and need a place to put up in? Would like to provide staff quarters for your company’s executives? Need centrally-located office space? Dream of a peaceful holiday home to stay at, over week-ends? Whatever be your home or work-place needs, we’ll help you! Be it an apartment, bungalow, farmhouse, plot or land ; an office, shop, showroom, mall or multiplex. That’s right. Since 1984, Space Management has been tending to all your Real Estate needs – be it buying, selling or renting, commercial or residential property. All at prime locations in Western Ahmedabad, such as Ashram Road, C.G. Road, Sarkhej-Gandhinagar Highway, Sardar Patel Ring Road, Ambawadi, Navrangpura, Mithakhali, Ellisbridge, Satellite, Vastrapur, Drive-in, Bodakdev (Judges’ Bungalows Road)… We consider ourselves fortunate to have been able to serve over a thousand clients down the years. And that includes a wide cross-section of Individuals, Corporates, Government bodies, Banks, NGOs etc. -

Life Membership 2011-18 Dec Telephone

LIFE MEMBERSHIP 2011-18 DEC TELEPHONE . Sl.No Name Designation ADDRESS NO SABZAZRE_NASEEBA-17,Muslim 1 A A MUNSHI HD Pharmasist soc. Navrangpura, AHMEDABAD 9979148439 380009. Gineshwar part - I Nr Kanti part 2 A B PANT EE(D) society,Ghatlodia Ahmedabad- 27604204 380061 B-32, Orchid park nr Shailby Hospital 3 A C Bajaj Mgr(Logistic) 9904981023 opp. Karnavati c;lub Satelite , A-22,Park Avenue New cg 4 A C Barua Dy.SE(P) 9427336696 roadChandkheda Ahmedabad-380005 22,Somvil Bunglows,Bhaikaka Nagar 5 A C Saini SE(P) Thaltej Ahmedabad-55 B-302.Chinubhai Tower Satelite 6 A D PATEL SE(P) 9428563893 Memnagar AHMEDABAD-52. 27,Konark Society Sabarmati 7 A D VAID DySE(E) 9898218428 Ahmedabad -380019 A-9 AL-Ashurfi Society,B/H Haider 8 A G SHAIKH AEE(P) Nagar, JUHAPAURA, Sarkhej Road 9428330591 AHMEDABAD 380055 B-27, Shardakrupa Society, B/H 9 A H Naik Dy. SE(P) Janatanagar Chandkheda, 27516085 GANDHINAGAR-382424. 66/7 Madini Chamber ,Mahakali 10 A I Shaikh AE(M) Temple Dudeshwar Shahibaug 9824591030 Ahmedabad 8 Sindhu Mahal soc. Ashram road Old 11 A J Sharma DM(HR) 9428008152 Vadaj Ahmedabad 380013. D-303 Aditya residency Motera 12 A K Dhawan GM(Res) 9428332121 Ahmedabad 380005. H-6,Karnavati Soc.GHB Chandkheda 13 A K GAHLAUT GM(P) 23296926 Ahmedabad-382424 Flat no 1001 Sangath Diomond 14 A K Gupta Exe.Director Tower nr PVR cinema Motera 9712922825 Ahmedabad 380005. 2nd floor Rituraj Apartment op Rupal 15 A K Gupta DGM(MM) flats nr Xavier Loyla school 9426612638 Ahmedabad B-77,RJESHWARI 09428330135- 16 A K MEHTA EE(M) SOCIETY,PO,TRAGAD,IOC ROAD 27508082 CHANDKHEDA AHMEDABAD-382470. -

FULL LIST for WEB UPLOAD GUJARAT.Xlsx

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Gujarat State as per following details: Estimated Security Fixed Fee / monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Finance to be arranged Mode of Deposit( Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Minimum Sales Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * by the applicant Selection Rs. in Bid amount Potential # Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 CC / DC / SC CFS SC CC-1 SC CC-2 SC PH Estimated Estimated ST fund working ST CC-1 required capital Draw of Regular / MS+HSD in ST CC-2 for ST PH Frontage Depth Area requireme Lots / Rural Kls developme OBC nt for Bidding nt of OBC CC-1 operation infrastruct OBC CC-2 of RO OBC PH ure at RO OPEN OPEN CC-1 OPEN CC-2 OPEN PH 1 GANGARDI TO BHARASADA DAHOD RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 2 SALARA TO KARODIYA VILLAGE ON FATEHPURA-BATAKWADA ROAD DAHOD RURAL 100 ST CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 FROM MOTA VARACHHA LAKE GARDEN TO GOTHAN VILLAGE ON 3 MOTA VARCHHA-GOTHAN ROAD SURAT RURAL 130 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Ubharan in Malpur taluka Arvalli district ARAVALLI RURAL 200 ST CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 5 VILLAGE BHOROL ,TALUKA THARAD BANASKANTHA RURAL 130 ST CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 6 VILLAGE CHELA BEDI JAMNAGAR RURAL 95 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 7 Kadiyali Village not on NH and SH AMRELI RURAL 73 ST CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 SANGMA TO PADRA ON BHOJ PADRA VADODARA ROAD -

A Presentation on Land Use and Urban Transport

ICRIER’s Program on Capacity Building and Knowledge Dissemination 31st August 2012 GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT A PRESENTATION ON LAND USE AND URBAN TRANSPORT By I.P.GAUTAM, IAS PRINCIPAL SECRETARY, URBAN DEVELOPMENT & URBAN HOUSING DEPARTMENT, GANDHINAGAR , GUJARAT URBAN DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE • Gujarat : One of the Most Urbanized States in the Country. Accounts for 6% of the total geographical area of the Country Around 5% of the Country’s population of 1.21 billion. Total Population of Gujarat 60.4 million State Urban Population 25.7 million (42.58%) Gujarat Urban Population Gujarat Rural Population National Urban Population 31.16% 42.58% 57.42% State Urban Population 42.58% 0 10 20 30 40 50 Source : Census 2011 ( Provisional Figures) URBAN PROFILE Municipal Corporations : 8 Municipal Municipalities :159 Corporation Constituted UDAs/ADAs : 16 Designated ADAs :113 STATE URBAN BUDGET Plan Outlay: Urban Development Department 6000 5670 5000 4000 2868 3030 in Cr. 3000 2367 ` 2000 1819 1137 1000 454 126 250 0 (1 crore = 10 million) GUJARAT URBAN DEVELOPMENT MODEL VISION Creating Clean , Green, Efficient, Vibrant, Productive and Sustainable Cities within a reasonable time-frame with due thrust on People’s Participation and Public-Private Partnership • Vision outlined in Urban Year-2005 • Pro-active participation in JnNURM • Garib Samrudhi Yojana -2007 & 2012 (Empowerment of Urban Poor) • Nirmal Gujarat Campaign – 2007 • Regulation for Residential Township, 2009 • Regulation for the Rehabilitation and Redevelopment of the Slums, 2010 • Swarnim Jayanti -

Affiliated Colleges & Recognised Institutions Part

AFFILIATED COLLEGES & RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS PART (A) AFFILIATED COLLEGES ARTS COLLEGES : (14) BD ARTS (024) B. D. Arts College for Women, City Campus, Opp. Din bai Tower, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad – 380 001. (Founded 1956) (G) (NAAC - B Grade) Time : 12-00 to 5-00 (079) 25500004 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Economics, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Home Science, Psychology, Sanskrit, Sociology, B.A. (Subsi.) Persian, Prakrit, Political Science, Statistical Method, M.A. Home Science, Sanskrit. Principal : Dr. Geetaben P. Mehta (079) 26611940 (M) 9825017019 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected] CU ARTS ( 036) C. U. Shah Arts College, Lal Darwaja, Nr. Dinbai Tower, Ahmedabad – 380 001. (Founded 1960) (E+G) (NAAC - B Grade) Time : 7-45 to 12-40 Tele Fax : (079) 25506703 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Gujarati, Hindi, Sanskrit, English, Economics, Political Science, History, Statistical Method, Psychology, Sociology, M.A. Psychology. Principal : Dr. S. K. Trivedi (Offg) (079) 27461233 (M) 9426048955 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] MANI ARTS (384) Goverment Arts College, Bihari mill compound, Khokhra road, Maninagar (East), Ahmedabad – 380 008. (Founded 2007) (G) Time : 11-00 to 16-00 (079) 22932516 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) Economics, English, Gujarati, Psychology, Sanskrit, (Subsi.) Indology Principal : Dr. Geetaben G. Pandya (079) 26302184 (M) 9426709133 e-mail : [email protected]; [email protected] LD ARTS (005) L. D. Arts College, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad – 380 009. (Founded 1937) (E + G) (NAAC - A Grade) Time : 7-30 to 12-30 (079) 26306619 Fax : 26302260 Subjects : B.A. (Prin.) & (Subsi.) English, Sanskrit, Gujarati, History, Economics, Hindi, Political Science, Psychology, Sociology, Geography, B.A. -

Trinity Brochure 09Aug20

Go for Growth Go for Trinity SALES ENQUIRY: 8000 58 5555 | SWATIPROCON.COM 11 th Floor, Signature One, S.G.Highway, Divya Bhaskar Road, Ahmedabad, India. Pocket Friendly Premium Oices & Showrooms at S.P.Ring Road, Near South Bopal Go for the Future Built with the three-tower architecture, Swati Trinity addresses 3 business needs: A future proof address: S.P.Ring Road. Lifespaces for a holistic oice experience. Premium yet pocket-friendly investment. Go for Trinity Go for Visibility Catch hold of the eyeballs with our front-facing retail spaces on S.P. Ring-road. More visibility. More footfalls. More business. Go for Trinity Go for Profit The only premium, front facing oice spaces within the 4km radius of the SP Ring Road. Go for Trinity Go for Globalization At Swati Trinity, you own more than just your oice space. Access the corporate lounges and conference rooms to make your meetings, and video calls truly global. Go for Trinity Go for Productivity Corporate Suite Activity Lounge Conference Room Cafetaria 3 High Speed Elevators Seperate Service Li Two Four Level in Each Block in Each Block Staircases Parking Go for Trinity 18.00 MT. WIDE T.P.S. ROAD 12.00 MT WIDE SERVICE ROAD GROUND FLOOR PLAN 18.00 MT. WIDE T.P.S. ROAD 12.00 MT WIDE SERVICE ROAD 1ST - 3RD FLOOR PLAN 18.00 MT. WIDE T.P.S. ROAD 12.00 MT WIDE SERVICE ROAD 4TH FLOOR PLAN 18.00 MT. WIDE T.P.S. ROAD 12.00 MT WIDE SERVICE ROAD 5TH FLOOR PLAN 1.