The Use of Population Reduction As a Technique to Combat Rabies in Alberta, Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 3

Centre Canadian Canadien Cooperative Coopératif de la Wildlife Santé Health Centre de la Faune Newsletter Volume - 3, Winter 1995 In this issue: CCWHC News Loon Survey to Continue in 1996 on a Meet More CCWHC Staff Fully National Scale Feature Articles Newcastle Disease in Double-crested Waterfowl Die-off in Mexico Cormorants - Summer 1995 The Northward March of Raccoon Rabies Rabbit Viral Hemorrhagic Disease on the - Update Loose in Australia Disease Updates Atlantic Region: Common Loons: Complex Causes of Verminous pneumonia in red foxes Mortality Quebec Region Parvovirus in Raccoons Giardia in Voles Beluga Whales in the St Lawrence Estuary Ontario Region: Insecticide Poisoning in Robins Emaciated Great Horned Owls Parvovirus and Trichinosis in Urban Raccoons Western and Northern Region: Botulism At Pakowki Lake, 1995. The Case of the Killer Cookies: Apparent Chocolate Poisoning of Gulls Unusual Mortality of Franklin's Gulls in Pelican deaths caused by storm Saskatchewan Pesticide poisonings in eagles - Update CCWHC News Loon Survey to Continue in 1996 on a Fully National Scale Over the past two years, a special effort has been made to secure specimens of loons found dead in the wild. The major emphasis has been on the Atlantic and Ontario regions. The purpose of this survey has been to gain a better understanding of the causes of mortality in loons, particularly the Common Loon (Gavia immer), and of the occurrence and relative importance of lead poisoning associated with ingestion of lead weights used in angling. Some of the impetus for this survey has come from the Toxicology Division of the Canadian Wildlife Service. -

Regional Base

4 Twp11 Rge16 W4 1 W4 Jensen Twp11 Rge20 W4 Twp11 Rge17 W 4 Rge12 W4 Twp11 Rge1 Twp11 Rge14 W4 Twp11 Rge13 W Twp11 3 L W4 Rge18 W4 Twp11 Rge15 Twp11 3 L Twp11 Rge19 W4 864 6 BOW ISLAND 4 7 Twp11 Rge21 W4 2 9 879L Twp10 Rge12 W4 L Twp10 Rge8 W4 PICTURE BUTTE 3 519 Twp10 Rge19 W4 W4 2 Twp10 Rge13 9 Burdett 0 W4 Twp10 Rge21 W4 p10 Rge14 W4 Juno Twp10 Rge1 4 Twp10 Rge15 W4 Tw Twp10 Rge11 W4 Twp10 Rge9 W 18 W4 Grassy Lake Twp10 Rge20 W4 D80 Twp10 Rge Twp10 Rge17 W4 Twp10 Rge16 W4 Shaughnessy Fincastle Lake Purple Springs Antonio Approved CPR Reservoir 36 0L D40 D60 61 612L Picture Butte 172L Taber Lake Fincastle Murray Lake Park Substation 120S D100 TABER Lake 3 Diamond City D20 E40 E60 E80 Sherburne Lake E20 Johnson's Addition Yellow Lake L 2 Twp9 Rge8 W4 2 e10 W4 7 Twp9 Rg 9 W4 843 Chin Cranford A Twp9 Rge11 W4 Twp9 Rge 3 Twp9 Rge12 W4 770L Tempest Barnwell Twp9 Rge14 W4 25 845 e17 W4 Twp9 Rge21 W4 Twp9 Rg 877 2EL Horsefly Lake Reservoir Twp9 Rge22 W4 Twp9 Rge20 W4 17 4 Twp9 Rge15 W Twp9 Rge13 W4 Broxburn Stafford Twp9 Rge16 W4 COALDALE Maleb 3A Stafford Village Reservoir D120 Fairview 512 4 p8 Rge8 W4 3 Twp8 Rge9 W Tw Twp8 Rge10 W4 W4 513 Twp8 Rge17 Twp8 Rge16 W4 Twp8 Rge12 W4 820AL Rge15 W4 Twp8 Rge13 W4 820L Twp8 Twp8 Rge14 W4 Proposed Etzikom Coulee Chin Lakes D140 Twp8 Rge11 W4 LETHBRIDGE Twp8 Rge18 W4 to Whitla routes Proposed ge20 W4 L Twp8 R 5 4 A10 Whitla 72 B20 A140 A120 A40 Substation 251S TwPpr8o Rpgoe2s1e Wd4 Picture Butte to G20 E100 G40 A160 A100 A60 Twp8 Rge22 W4 Etzikom Coulee routes Twp7 Rge11 W4 A20 L Twp7 Rge8 W4 508 Twp7 Rge19 W4 7 A80 4 0 4 Twp7 Rge16 W 6 B60 Twp7 Rge9 W p7 Rge14 W4 Wilson Tw B80 A220 A200 B40 Twp7 Rge10 W4 7 Rge17 W4 E120 Twp7 Rge18 W4 Twp B120 B100 Twp7 Rge12 W4 C20 ge21 W4 Twp7 Rge22 W4 Twp7 R A180 G60 885 Blood E140 B200 Twp7 Rge15 W4 B140 Twp6 Rge8 W4 No. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

December 15, 2017 Wade Vienneau Executive Director, Facilities Alberta

December 15, 2017 Wade Vienneau Executive Director, Facilities Alberta Utilities Commission 400, 425 – 1st Street SW Calgary, AB, T2P 3L8 Dear Mr. Vienneau: Re: Alberta Electric System Operator (“AESO”) Alberta Utilities Commission (“Commission”) Proceeding 171; Application No. 1600682; Needs Identification Document (“NID”) for the Southern Alberta Transmission Reinforcement (“SATR”); SATR Milestones and Monitoring Process (“MMP”) Status Report for Q4 2017 The AESO writes in connection with the SATR NID Application,1 the most recent SATR NID approval issued by the Commission, being Needs Identification Document Approval 21190-D04-2016, dated June 9, 2016,2 and the SATR MMP approved by the Commission in Decision 2010-343 dated July 19, 2010.3 Enclosed with this letter is an update to the AESO’s SATR Construction Milestones report as of Q4 2017 (“Status Report”). The Status Report summarizes the status of the different SATR construction milestone measures used to confirm the need for the transmission developments approved as part of SATR. Contemporaneous with the filing of this letter, the AESO is posting a copy of the Status Report on its website, and will be including a link to the Status Report in its next stakeholder newsletter. In the original SATR NID, approved by the Commission on September 8, 2009, the AESO indicated that, if an identified trigger for the different components of SATR did not occur by the end of 2017, then the approval of the need related to such trigger would cease to be of any effect, and would have to be 1 Proceeding 171, Exhibit 0001.00.AESO-171. 2 Commission Needs Identification Document Approval 21190-D04-2016, Alberta Electric System Operator Amendment to Southern Alberta Transmission Reinforcement (June 9, 2016). -

Mixed Grassland (#156)

MIXED GRASSLAND (#156) The Mixed Grassland ecoregion is the southernmost and driest of Canada’s prairie ecoregions. A northern extension of the shortgrass prairies that stretches south to Mexico, this ecoregion is characterized by the vast open grasslands of the Great Plains, with prairie potholes and several large shallow lakes. It provides habitat for over 35 species at risk and is an important region for waterfowl nesting. The semi-arid climate limits crop production. Approximately 42% of this ecoregion remains in natural cover and almost 11% is within conserved/ protected areas, including 4% in community pastures. LOCATION Arching from southcentral Saskatchewan to southcentral Alberta along the U.S. border, this ecoregion forms the northern part of the semi-arid shortgrass prairie in the Great Plains of North America. This ecoregion extends southward along the Missouri River into northeastern Montana, northwest and central North Dakota, and central South Dakota (in the U.S., this ecoregion is called the Northwestern Mixed Grasslands). CLIMATE/GEOLOGY The Mixed Grassland ecoregion generally has long, dry and cold winters, with a short, warm and a relatively wet spring and summer. The mean annual temperature is approximately 3.5⁰C. Mean summer tempera- ture is 16⁰C and mean winter temperature is approximately -10⁰C. The mean annual precipitation ranges from 240 to 350 millimetres, with higher rain and snowfall in the eastern portion. Overall, this ecoregion is semi-arid, and compared to other regions of the Prairies, it has rela- tively low amounts of snow cover. Western sections of the ecoregion experience a higher frequency of warming Chinook winds in the winter. -

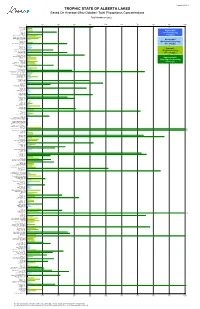

Trophic State of Alberta Lakes Based on Average Total Phosphorus

Created Feb 2013 TROPHIC STATE OF ALBERTA LAKES Based On Average (May-October) Total Phosphorus Concentrations Total Phosphorus (µg/L) 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 * Adamson Lake Alix Lake * Amisk Lake * Angling Lake Oligotrophic * ‡ Antler Lake Arm Lake (Low Productivity) * Astotin Lake (<10 µg/L) * ‡ Athabasca (Lake) - Off Delta Baptiste Lake - North Basin Baptiste Lake - South Basin * ‡ Bare Creek Res. Mesotrophic * ‡ Barrier Lake ‡ Battle Lake (Moderate Productivity) * † Battle River Res. (Forestburg) (10 - 35 µg/L) Beartrap Lake Beauvais Lake Beaver Lake * Bellevue Lake Eutrophic * † Big Lake - East Basin * † Big Lake - West Basin (High Productivity) * Blackfalds Lake (35 - 100 µg/L) * † Blackmud Lake * ‡ Blood Indian Res. Bluet (South Garnier Lake) ‡ Bonnie Lake Hypereutrophic † Borden Lake * ‡ Bourque Lake (Very High Productivity) ‡ Buck Lake (>100 µg/L) Buffalo Lake - Main Basin Buffalo Lake - Secondary Bay * † Buffalo Lake (By Boyle) † Burntstick Lake Calling Lake * † Capt Eyre Lake † Cardinal Lake * ‡ Carolside Res. - Berry Creek Res. † Chain Lakes Res. - North Basin † Chain Lakes Res.- South Basin Chestermere Lake * † Chickakoo Lake * † Chickenhill Lake * Chin Coulee Res. * Clairmont Lake Clear (Barns) Lake Clear Lake ‡ Coal Lake * ‡ Cold Lake - English Bay ‡ Cold Lake - West Side ‡ Cooking Lake † Cow Lake * Crawling Valley Res. Crimson Lake Crowsnest Lake * † Cutbank Lake Dillberry Lake * Driedmeat Lake ‡ Eagle Lake ‡ Elbow Lake Elkwater Lake Ethel Lake * Fawcett Lake * † Fickle Lake * † Figure Eight Lake * Fishing Lake * Flyingshot Lake * Fork Lake * ‡ Fox Lake Res. Frog Lake † Garner Lake Garnier Lake (North) * George Lake * † Ghost Res. - Inside Bay * † Ghost Res. - Inside Breakwater ‡ Ghost Res. - Near Cochrane * Gleniffer Lake (Dickson Res.) * † Glenmore Res. -

Western Grebe Surveys in Alberta 2016

WESTERN GREBE SURVEYS IN ALBERTA 2016 The western grebe has been listed as a Threatened species in Alberta. A recent data compilation shows that there are approximately 250 lakes that have supported western grebes in Alberta. However, information for most lakes is poor and outdate d. Total counts on lakes are rare, breeding status is uncertain, and the location and extent of breeding habitat (emergent vegetation, usually bulrush) is usually unknown. We are seeking your help in gathering more information on western grebe populations in Alberta. If you visit any of the lakes listed below, or know anyone that does, we would appreciate as much detail as you can collect on the presence of western grebes and their habitat. Let us know in advance (if possible) if you are planning on going to any lakes, and when you do, e-mail details of your observations to [email protected]. SURVEY METHODS: Visit a lake between 1 May and 31 August with spotting scope or good binoculars. Surveys can be done from a boat, or vantage point(s) from shore. Report names of surveyors, dates, number of adults seen, and report on the approximate percentage of the lake area that this number represents. Record presence of young birds or nesting colonies, and provide any additional information on presence/location of likely breeding habitat, specific parts of the lake observed, observed threats to birds or habitat (boat traffic, shoreline clearing, pollution, etc.). Please report on findings even if no birds were seen. Lakes on the following page that are flagged with an asterisk (*) were not visited in 2015, and are priority for survey in 2016. -

Natural Gas in the Province of Alberta, Canada

T.P. 3398 NATURAL GAS IN THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA, CANADA J. F. DOUGHERTY, EMPIRE TRUST CO., NEW YORK, N. Y., MEMBER AIME; ANTHONY FOLGER, DeGOLYER AND Downloaded from http://onepetro.org/JPT/article-pdf/4/10/241/2238979/spe-952241-g.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 MacNAUGHTON, DALLAS, TEX.; HOWARD R. LOWE, DElHI OIL CORP., DALLAS, TEX.; JOFFRE MEYER AND E. G. TROSTEL, DeGOL YER AND MacNAUGHTON, DAllAS, TEX., MEMBERS AIME ABSTRACT have been found since 1945. Sixty fields currently are produc ing gas, including 22 non-associated gas accumulations. The status of the natural gas industry in Alberta, Canada, Location of the oil and gas fields and prospects in the is described with particular reference to the current extent province of Alberta is shown in Fig. 1, together with a list of natural gas reserves and possibilities for additional develop of the localities of measurable gas, Fig. 1A. ment. Certain major fields are discussed as representative of The estimated total provincial gas reserve as of Jan. 1, 1952, the types of gas accumulations within various broad geographi for the 104 fields estimated, is 11.7 trillion cu ft proved and cal divisions of the provinces. The estimation of the future probable, and for the 187 known areas capable of production performance of a gas reservoir is discussed as the basis for is in excess of 16 trillion cu ft on a total proved, probable, and an estimate of the future availability of natural gas from possible basis. Five fields (Pincher Creek, Leduc-Woodbend, presently known reserves. -

Salinity Mapping for Resource Management Within the County of Warner, Alberta

Salinity Mapping for Resource Management within the County of Warner, Alberta J. Kwiatkowski L.C. Marciak D. Wentz C.R. King Conservation and Development Branch Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development March 1996 Abstract This report presents a methodology to map salinity at a municipal scale and applies this procedure to the County of Warner, a municipality in southern Alberta. The methodology was developed for the County of Vulcan (Kwiatkowski et al. 1994) and is being applied to other Alberta municipalities which have identified soil salinity as a concern. Soil salinity is a major land degradation issue in the County of Warner. The information on salinity location, extent, type and control measures presented in this report will help County planners to target salinity control and resource management programs. The methodology has four steps: 1. The location and extent of saline areas are mapped based on existing information including aerial photographs, maps, satellite imagery, and information from local personnel and field inspections. 2. Saline areas are classified on the basis of the mechanism causing salinity. The mechanism is important because it determines which control measures are appropriate. Eight salinity types are recognized within Alberta but only seven are found in the County of Warner. These are: contact/slope change salinity, outcrop salinity, artesian salinity, depression bottom salinity, coulee bottom salinity, irrigation canal seepage salinity and natural/irrigation salinity. There is no evidence that slough ring salinity occurs in the County. 3. Cost-effective, practical control measures are identified for each salinity type. 4. Colour-coded maps at 1:100 000 and 1:200 000 are prepared showing salinity location, extent and type. -

Provincial Electoral Divisions

Thabacha Náre Tsu Túe Indian Reserve Indian Reserve No. 196A Leland Lakes CharlesNo. 196G Lake Thebathi No. 225 W Indian Reserve Li Dezé B Charles Lake h u No. 196 Indian Reserve i f t f No. 196C e a Tthe Jere Ghaili Tsu K’adhe Túe s l Bistcho Lake o Jackfish a Indian Reserve Indian Reserve Point n No. 196F d Collin Lake R No. 196B No. 214 Cornwall Lake i Hokedhe Túe No. 223 v r Y e Cornwall R Bistcho a Indiane Reserve Colin Lake r t i v Lake No. e i Lake s v No. 196E e R 224 No. 213 R r iv e e r v a l S Wood Buffalo National Park r e iv R y Peace Point a Amber H Upper No. 222 Lake River Hay River Wentzel Lake Sandy Point Athabasca No. 219 No. 212 No. 221 r Margaret Lake Devil’s Gate e iv No. 220 Allison Bay Zama Lake R No. 210 Hay Lake No. 219 No. 209 Peace River n Baril Lake Zama Lake o t Dog Head n o No. 218 P Chipewyan Mamawi Lake C Beaver Lake Claire No. 201B Chipewyan h Ranch No. 201A i John D’Or n No. 163B RAINBOW c HIGH Child Lake Prairie Chipewyan h LAKE a LEVEL No. 164A Beaver No. 215 Fox No. 201C g Bushe Lake a River Boyer Ranch Richardson Lake No. 163 No. 162 No. 207 No. 164 r Old Fort R ive Ft. Peace R No. 217 i v Vermilion e r No. -

Avian Botulism in Alberta: a History

Ecology and Management of Avian Botulism on the Canadian Prairies Prepared for: Prairie Habitat Joint Venture Science Committee, August 2011 ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF AVIAN BOTULISM ON THE CANADIAN PRAIRIES Primary Authors: TRENT K. BOLLINGER1, DANIEL D. EVELSIZER3, KEVIN W. DUFOUR2,3, CATHERINE SOOS1,2, ROBERT G. CLARK2,3, GARY WOBESER1, F. PATRICK KEHOE4, KARLA L. GUYN4, and MARGO J. PYBUS5 Additional Contributors: Henry Murkin4, Brett Calverley4, Meagan Hainstock4 The following individuals are recognized and thanked for their strong support and leadership of PHJV’s response to avian botulism: Bruce Batt, Ducks Unlimited Inc. (retired) Brian Gray, Ducks Unlimited Canada (currently, Environment Canada) Bill Gummer, Canadian Wildlife Service (retired) Gerald McKeating, Canadian Wildlife Service (retired) Cover Page Design: Jeope Wolfe4 1 Department of Veterinary Pathology, University of Saskatchewan 2 Environment Canada, Prairie and Northern Wildlife Research Centre 3 Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan 4 Ducks Unlimited Canada 5 Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Sustainable Resource Development i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Avian botulism (Clostridium botulinum, Type C; hereafter ‘botulism’) has occurred on the Prairies and elsewhere for centuries. Botulism affects varying numbers of birds, often in multiple locations, at some time virtually every year. After the formation of the Prairie Habitat Joint Venture (PHJV) in 1988, and as early as 1994, it was becoming increasingly apparent that very large numbers of ducks and shorebirds were dying annually during botulism outbreaks at several large wetlands on the Canadian Prairies. The magnitude of these losses created considerable consternation in the North American waterfowl and wildlife management community. At the time, wetland surveillance and carcass removal (or ‘clean-up’) were used to try to limit the severity of these outbreaks, but the efficacy of this approach was unknown. -

Plant Community Classification of the Pakowki Sandhills and Sand Plains

Plant Community Classification of the Pakowki Sandhills and Sand Plains Prepared for: Resource Data Branch Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Edmonton, Alberta Prepared by: Valerie Coenen Jerry Bentz Geowest Environmental Consultants Ltd. Suite 203, 4208 – 97 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada T6E 5Z9 January, 2003 Plant Community Classification of the Pakowki Sandhills and Sand Plains Executive Summary The Resource Data Division of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development contracted Geowest Environmental Consultants Ltd. to produce a classification of sand dune and sand plain plant community types within the Grassland Natural Region of Alberta. This initiative is in support of the Alberta Natural Heritage Information Centre (ANHIC). ANHIC collects, evaluates and makes available data on elements of natural biodiversity in Alberta, including flora, fauna and native plant communities. ANHIC develops tracking lists of elements that are considered of high priority because they are considered rare or special in some way. ANHIC’s long-term goal is to develop a list of plant community types that occur throughout the province and to attempt to identify community types that require conservation initiatives. The primary objective of this project was to develop a plant community classification of sand dune and sand plain plant communities of the Grassland Natural Region based on field survey, correlations with other surveys and any available previously-collected data. Furthermore, each identified community type was evaluated and assigned a preliminary provincial rank, based on its rarity/endemism or threats to its condition. This was accomplished by developing a sampling protocol and subsequently collecting field data on plant communities of the sand dune and sand plain landscapes of the Pakowki Sandhills.