Reconsidering the Historical Marker on Mount Bonnell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Austin Housing

GUIDE TO AUSTIN HOUSING This list is provided as a courtesy to scholars. Inclusion on the list does not constitute an endorsement by the Ransom Center, nor does it provide a guarantee of the quality of a given establishment’s services. Information is thought to be accurate as of the date of compilation; the Ransom Center cannot be responsible for errors or omissions. It is the visitor’s responsibility to contact establishments to confirm current rates and other details according to his or her own needs. The Ransom Center is unable to provide assistance with reservations or arrangements. This list is organized by establishment type (private residences, bed and breakfasts, hotels, etc.). Establishments within each section of this list appear in the order of their distance from the Ransom Center, from nearest to farthest. The heading of each entry provides the establishment’s location, which may be used to determine transportation options. Please be aware that not all establishments are located on a direct bus route to campus, and some routes may have recently changed due to a 2018 update to Austin’s public transportation system. Please see the “Public Transportation” section below for further information about researching public transportation options between a particular location and the Ransom Center. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION For complete and current information about public transportation in Austin, visit www.capmetro.org. The “Plan Your Trip” section of this website offers point-to-point directions using the public transportation system. The Ransom Center is located at 300 West 21st Street, Austin, Texas, 78712. PRIVATE RESIDENCES: LESS THAN 1.5 MILES FROM THE RANSOM CENTER 209 West 33rd Street Newly renovated 1 bed, 1 bath, 550 sq. -

Ii.2. Meridian Highway (Sh 2) – Us 81 – Ih 35/35W

The Development of Highways in Texas: A Historic Context of the Bankhead Highway and Other Historic Named Highways II.2. MERIDIAN HIGHWAY (SH 2) – US 81 – IH 35/35W INTRODUCTION The Meridian Highway historically has been the major north–south named highway in Texas since the early 1910s. As originally conceived by the International Meridian Road Association in 1911, it stretched from Canada to Mexico, extending through the nation’s mid-section and the expansive Great Plains region. It initially was planned to enter Texas near Burkburnett and continued south through Wichita Falls, Bowie, Fort Worth, Cleburne, Waco, Austin, San Antonio and Laredo. A major lateral, called the Gulf Division, was planned to extend from Waco to Galveston, passing through Marlin, Bryan, Hempstead, and Houston. (See Figure 164.) With the creation of the Texas Highway Department in 1917, the Meridian Highway in Texas was designated as SH 2, signifying that the Texas Highway Commission deemed it to be the state’s second most important highway at the time, after the Bankhead Highway (SH 1). The adoption of the AASHO interstate highway numbering plan added another designation layer onto the Meridian Highway: US 81. That name, rather than SH 2, has endured over time. However, US 81 did not follow the route proposed by the Meridian Road Association precisely. The creation of US 81 in Texas excluded the Wichita Falls– Bowie leg, which was renamed as US 277 and, later, US 370. The Gulf Division also was excluded from the route of US 81; instead, it became SH 6 and, later, US 75. -

Geophysical Mapping of Mount Bonnell Fault of Balcones Fault Zone

Geophysical mapping of Mount Bonnell fault of Balcones fault zone and its implications on Trinity-Edwards Aquifer interconnection, central Texas, USA Mustafa Saribudak1 Abstract There are up to 1200 ft (365 m) of total displacement across the Geophysical surveys (resistivity, natural potential [self-po- BFZ. Faults generally dip steeply (45–85°), varying primarily tential], conductivity, magnetic, and ground penetrating radar) due to specific rock properties and local stress fields (Ferrill and were conducted at three locations across the Mount Bonnell fault Morris, 2008). in the Balcones fault zone of central Texas. The normal fault has The BFZ includes the Edwards and Trinity aquifers, which hundreds of meters of throw and is the primary boundary between are primary sources of water for south-central Texas communities, two major aquifers in Texas, the Trinity and Edwards aquifers. including the city of San Antonio. The Trinity Aquifer underlies In the near surface, the fault juxtaposes the Upper Glen Rose the Edwards Aquifer through the Balcones fault zone. Formation on the Edwards Plateau, consisting of interbedded The BFZ’s most prominent fault is the Mount Bonnell, with limestone and marly limestone, against the Edwards Group, which a vertical throw of up to 600 ft (183 m) (Figure 1). The fault is mostly limestone, on the eastern down-thrown side (coastal hydrogeologically juxtaposes these Cretaceous carbonate aquifers plain). The Upper Glen Rose member is considered to be the during the Miocene tectonic deformation associated with the Upper Trinity Aquifer and also a confining zone underlying the Balcones fault zone, where the younger Edwards Group limestone Edwards Aquifer. -

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program Created by the Cadette and Senior Girl Scout attendees of Zilker Day Camp 2003, Session 4. This patch program is a great program to be completed in conjunction with the new Capital Metro Patch Program available at gsctx.org/badges. PATCHES ARE AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE IN GSCTX SHOPS. Program Grade Level Requirements: • Daisy - Ambassador: explore a minimum of eight (8) places. Email [email protected] if you find any hidden gems that should be on this list and share your adventures here: gsctx.org/share EXPLORE 1. Austin Nature and Science Center, 2389 Stratford Dr., (512) 974-3888 2. *The Contemporary Austin – Laguna Gloria, 700 Congress Ave. (512) 453-5312 3. Austin City Limits – KLRU at 26th and Guadalupe 4. *Barton Springs Pool (512) 867-3080 5. BATS – Under Congress Street Bridge, at dusk from March through October. 6. *Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress Ave. (512) 936-8746 7. Texas State Cemetery, 909 Navasota St. (512) 463-0605 8. *Deep Eddy Pool, 401 Deep Eddy. (512) 472-8546 9. Dinosaur Tracks at Zilker Botanical Gardens, 2220 Barton Springs Dr. (512) 477-8672 10. Elisabet Ney Museum, 304 E. 44th St. (512) 974-1625 11. *French Legation Museum, 802 San Marcos St. (512) 472-8180 12. Governor’s Mansion, 1010 Colorado St. (512) 463-5518 13. *Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave. (512) 232-0100 14. LBJ Library 15. UT Campus 16. Mayfield Park, 3505 W. 35th St. (512) 974-6797 17. Moonlight Tower, W. 9th St. -

4323 Mount Bonnell RD, Austin TX 78731

$9,995,000.00, 4323 Mount Bonnell RD, Austin TX 78731 MLS® 7650067 Rare development opportunity on this premier west Austin property that is beautifully positioned on a hill above Lake Austin and prestigious Mount Bonnell Road. The one-of-a-kind estate property offers ultimate privacy along with unparalleled views of Lake Austin, the Pennybacker Bridge, and the Hill Country. Brightleaf Nature Preserve surrounds the property and creates a natural sanctuary of beauty and tranquility. This 5.93- acre tract is conveniently located minutes from downtown Austin, nationally renowned restaurants, intimate music venues, boutique shopping, Lady Bird Lake, and the hike and bike trail. The central location provides ease and convenience to city living but allows a retreat to seclusion and privacy. This estate site provides an opportunity for your imagination to soar with the possibilities of creating the ultimate retreat. Imagine a private winding drive leading up the hillside where you are immediately captivated by the wrestling of trees and nature. As you approach the top of the hill you are greeted with unmatched lake views, beauty and tranquility. The building site allows vision to design, build, and curate an architectural gem nestled on the hillside above Lake Austin. This is a rare opportunity to own and build a fabulous estate property in central Austin. Listing Details MLS® # 7650067 Price 9,995,000.00 Status Active Type Land Sub-Type Single Lot Neighborhood Mount Bonnell Year Built Square Feet Lot Size 258310.8 Bedrooms 0 Bathrooms This information was printed from fuserealty.com on 10/02/2021. Use For more information about this or similar properties, contact Us The information being provided is for consumers' personal, non-commercial use and may not be used for any purpose other than to identify prospective properties consumers may be interested in purchasing. -

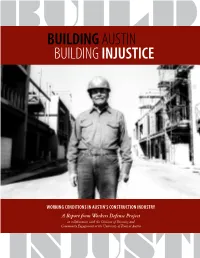

Building Austin, Building Injustice Study Was Undertaken by Workers Defense Project to Better Understand Working Conditions in Austin’S Construction Industry

BUILD BUILDING AUSTIN BUILDING INJUSTICE WORKing COnditiOns in Austin’S COnstRuctiON IndustRY A Report from Workers Defense Project in collaboration with the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin INJUSTIC Dedicated to the 142 Texas construction workers who died on the job last year, and to Austin’s hard working construction men and women whose contributions too frequently go unrecognized. © June 2009 Workers Defense Project EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Building Austin, Building Injustice study was undertaken by Workers Defense Project to better understand working conditions in Austin’s construction industry. Workers Defense Project is a non-profit community organization that promotes fair working conditions for Austin’s low-wage workers. Workers Defense Project partnered with faculty from the University of Texas at Austin, the Division of Diversity & Community Engagement of The University of Texas at Austin, and faculty from the University of Illinois at Chicago, to carry out one of the most comprehensive studies on the industry in the country. Building Austin, Building Injustice is the result of more than a year of research from data collected from primary and secondary sources, including surveys with 312 construction workers, 17 in-depth worker interviews, 20 in-depth interviews with industry leaders, and existing government data. The City of Austin has quickly become the second fastest-growing urban area in the country, depending heavily on the construction workforce to meet the demands for new housing, commercial buildings, and the city’s infrastructure system.1 Though the construction industry plays an important role in the local economy, working conditions in the industry have not been studied previously. -

TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America

Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America TRAIL REQUIREMENTS: 1. There should be at least one adult for each 10 hikers. A group must have an adult leader at all times on the trail. The Boy Scouts of America policy requires two adult leaders on all Scout trips and tours. 2. Groups should stay together while on the hike. (Large groups may be divided into several groups.) 3. Upon completion of the trail the group leader should send an Application for Trail Awards with the required fee for each hiker to the Capitol Area Council Center. (Only one patch for each participant.) The awards will be mailed or furnished as requested by the group leader. Note: All of Part One must be hiked and all points (1-15) must be visited. Part Two is optional. HIKER REQUIREMENTS: 1. Any registered member of the Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts, or other civic youth group may hike the trail. 2. Meet all Trail requirements while on the hike. 3. The correct Scout uniform should be worn while on the trail. Some article (T-shirt, armband, etc) should identify other groups. 4. Each hiker must visit the historical sites, participate in all of his/her group’s activities, and answer the “On the Trail Quiz” to the satisfaction of his/her leader. Other places of interest you may wish to visit are: Zilker Park and Barton Springs Barton Springs Road Elisabet Ney Museum 304 E. 34th. Street Hike and Bike Trail along Town Lake Camp Mabry 38th. Street Lake Travis FM #620 Lake Austin FM # 2222 Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America ACCOMODATIONS: McKinney Falls State Park, 5805 McKinney Falls Parkway, Austin, TX 78744, tel. -

Leffingwell, S. Lee: 2012 Candidate/Officeholder Campaign

Texas Ethics Commission P.O. Box 12070 Austin, Texas 78711-2070 (512)463-5800 TDD 1-800-735-2989 CANDIDATE / OFFICEHOLDER FORM C/OH CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORT COVER SHEET PG 1 2 PAGE ft The C/OH INSTRUCTION GUIDE explains how to complete this form. (Ethics Commissio ^ Tilers) 1of60 00999999 MS /MRS /MR FIRST 3 CANDIDATE/ Ml OFFICE USE ONLY OFFICEHOLDER Lee NAME Dale Received NICKNAME LAST SUFFIX ^ Leffingwell wC=3 > 4 CANDIDATE/ ADDRESS / PO BOX; APT / SUITE #; CITY; STATE; ZIP CODE ^P — 1 OFFICEHOLDER ^ m33 ^— MAILING P.O. Box 300787 rt ADDRESS *~J ° Austin, TX 78703 Dale Hand-delivered or"Date Fjp^lrrfjj'ited -o ^ ~< |X 1 Change of Address 13 o o JL 1 m Receipt # Amount -*J rx^ 7* 5 CAMPAIGN MS /MRS /MR FIRST Ml Data Processed — O TREASURER NAME Katheryn Date imaged NICKNAME LAST SUFFIX Kitty Clark 6 CAMPAIGN STREET ADDRESS (NO PO BOX PLEASE); APT / SUITE !»; CITY; STATE; ZIP CODE TREASURER ADDRESS 4308 Avenue D (Residence or business) Austin, TX 78751 7 CAMPAIGN AREA CODE PHONE NUMBER EXTENSION TREASURER PHONE (512)453-6246 8 REPORT TYPE |X| January 15 I I 30th day before election [ I Runoff | [ 15th day after campaign treasurer appointment (offce holder only) [~~] July 15 [~~| 8th day before election [~~] Exceeded $500 limit | [ Final report (Attach C/OH - FR) 9 PERIOD Month Day Year Month Day Year COVERED THROUGH 07/01/2011 12/31/2011 10 ELECTION ELECTION DATE ELECTION TYPE Month Da/ Year j— | Primafy J— j Runoff [x] General 1 j Special 05/12/2012 11 OFFICE OFFICE HELD (if any) 1 2 OFFICE S OUGHT (if known} Mayor Mayor GO TO PAGE 2 Electronic Filing Version 3,4.3 Texas Ethics Commission P.O. -

About Austin

Discover Austin City… no Limits! sponsor or endorser of SAA. ustin sustains many vibrant cultures and subcultures flourishing Downtown Austin looking across Lady Bird Lake. in a community that allows room for new ideas. The beauty of our (Lower Colorado River Authority) A green spaces, the luxury of a recreational lake in the middle of the city, historic downtown architecture blending with soaring new mixed-use high rises, and a warm climate provide inspiration and endless activities for citizens and visitors. BUILDINGS AND LANDMARKS If you haven’t heard the city’s unofficial motto yet, chances are you will In 1845, Austin became a state capital when the United States annexed the soon after arriving – “Keep Austin Weird” – a grassroots, underground Republic of Texas. The current capitol building was completed in 1888 on mantra that’s filtered upward, encouraging individuality and originality in an area of high ground, replacing the previous one that had burned with an every form. It’s an apt phrase, since from its beginnings Austin has imposing Renaissance Revival native pink granite and limestone structure, embodied an independent, unconventional spirit. the largest state capitol building in the nation. The dome is topped by the Goddess of Liberty, a zinc statue of a woman holding aloft a gilded Lone Star. From many vantage points downtown there are unobstructed views of the Capitol, planned for and protected by state law. Visitors are free to explore EARLY AUSTIN the beautifully maintained Capitol grounds and the building itself, where tour guides are available. The soaring interior of the Rotunda is a magnificent Austin began as the small, isolated frontier town of Waterloo, settled on the space and an excellent place to cool down during a summer walk. -

AUSTIN I.Q. TEST 1. Armadillo World Headquarters 2. Nothing Strikes

AUSTIN I.Q. TEST 1. Armadillo World Headquarters 2. Nothing Strikes Back 3. Soap Creek Saloon 4. Steak Island 5. Inner Sanctum 6. Andre’s 7. Hippie Hollow 8. Dry Creek Cafe 9. Vulcan Gas Co. 10. Oat Willie’s 11. The White House 12. Magic Mushroom 13. Luigi’s 14. Hill on the Moon 15. One Knight or One Nite 16. Mi Casa Es Su Casa 17. Common Market 18. The Veranda 19. Mama Eleni’s 20. The Rag 21. Salvation Sandwiches 22. The Drag 23. Texas Chili Parlor 24. Barton Springs 25. Inn at Brushy Creek 26. Salt Lick 27. Coupeland’s 28. Drag Vendors 29. Pumpkin Stomp 30. Uranium Savages 31. Windy Point 32. Paleface Park 33. Comanche Trail 34. The Draught House 35. The Hoffbrau 36. La Tapatia 37. Liberty Lunch 38. City Park 39. Marshall Ford 40. Hamilton’s Pool 41. Luckenbach 42. Milton Reimer’s 43. Casita Jorge’s 44. Greezy Wheels 45. Continental Club 46. Antone’s 47. The Garden Cafe 48. Chilympiad 49. Jim Franklin 50. Rikki, The Guacamole Queen 51. Eeyore’s Birthday Party 52. Mount Bonnell 53. The Stallion 54. Alamo Hotel 55. Fall Mall Ball 56. The Tree Safeway 57. Wild Basin 58. Jeff Friedman as Mayor 59. English’s Mercantile Company 60. The Saxon Pub 61. Journey’s End 62. The Posse 63. The Tavern 64. Gregory Gym 65. Hole-In-The-Wall 66. Sco Pro Lounge 67. Raul’s 68. Duke’s Royal Coach Inn 69. Austin Country 70. Moonlight Towers 71. Caravanserai 72. Pecan Street 73. -

The Contemporary Austin Announces the Latest

CONTACT: Nicole Chism Griffin, PR – The Contemporary Austin [email protected] / 512 453 5312 x 119 (P) / 206 947 2312 (C) THE CONTEMPORARY AUSTIN ANNOUNCES THE LATEST INSTALLATION IN ITS MUSEUM WITHOUT WALLS PROGRAM, FEATURING 22-FOOT TALL SCULPTURE BY FORMER UT FACULTY MEMBER DAVID DEMING INSTALLED AT PEASE PARK The public is invited to celebrate the installation of David Deming’s Mystic Raven in Pease Park, made possible through the financial support of the Edward and Betty Marcus Foundation and a partnership with Pease Park Conservancy. The Artist will be in attendance, along with City of Austin officials, executives from the Edward and Betty Marcus Foundation, The Contemporary Austin and Pease Park Conservancy, Pease Park neighbors, and art lovers from across the city. WHAT Public Celebration of The Contemporary Austin’s Museum Without Walls installation of David Deming’s Mystic Raven at Pease Park. The event formally celebrates the recent installation with remarks from city officials and refreshments for all attendees. Guests may meet the artist and learn more about this monumental work that has been previously exhibited in downtown Austin and at Laguna Gloria. The installation at Pease Park was approved by the City of Austin Arts Commission following careful review and a community engagement meeting. The piece will be on long term loan to Art in Public Places. WHEN Saturday, December 16, 2017 9 am – 11:00 am WHERE Pease Park, 29th Street and North Lamar Boulevard WHO The public is invited to celebrate with the artist, city officials, and others In attendance: David Deming, Artist Alison Alter, Austin City Council Member, District 10 Kimberly McNeeley, Acting Director, Austin Parks and Recreation Department Louis Grachos, Executive Director and CEO, The Contemporary Austin HOW The event is free and open to the public. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked.