Ageing, Gender and Dancers' Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•... -

Gender Inequity in Achievement and Acknowledgment in Australian Contemporary Dance

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2009 Architects of the identity of dance: Gender inequity in achievement and acknowledgment in Australian contemporary dance Quindell Orton Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Dance Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Orton, Q. (2009). Architects of the identity of dance: Gender inequity in achievement and acknowledgment in Australian contemporary dance. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1331 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1331 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

A Study on the Gender Imbalance Among Professional Choreographers Working in the Fields of Classical Ballet and Contemporary Dance

Where are the female choreographers? A study on the gender imbalance among professional choreographers working in the fields of classical ballet and contemporary dance. Jessica Teague August 2016 This Dissertation is submitted to City University as part of the requirements for the award of MA Culture, Policy and Management 1 Abstract The dissertation investigates the lack of women working as professional choreographers in both the UK and the wider international dance sector. Although dance as an art form within western cultures is often perceived as ‘the art of women,’ it is predominately men who are conceptualising the works and choreographing the movement. This study focuses on understanding the phenomenon that leads female choreographers to be less likely to produce works for leading dance companies and venues than their male counterparts. The research investigates the current scope of the gender imbalance in the professional choreographic field, the reasons for the imbalance and provides theories as to why the imbalance is more pronounced in the classical ballet sector compared to the contemporary dance field. The research draws together experiences and statistical evidence from two significant branches of the artistic process; the choreographers involved in creating dance and the Gatekeepers and organisations that commission them. Key issues surrounding the problem are identified and assessed through qualitative data drawn from interviews with nine professional female choreographers. A statistical analysis of the repertoire choices of 32 leading international dance companies quantifies and compares the severity of the gender imbalance at the highest professional level. The data indicates that the scope of the phenomenon affects not only the UK but also the majority of the Western world. -

American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic: Orientalism, Feminism, and Popular Culture

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2010 American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic: Orientalism, Feminism, and Popular Culture Jennifer Lynn Haynes-Clark Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Haynes-Clark, Jennifer Lynn, "American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic: Orientalism, Feminism, and Popular Culture" (2010). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 20. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic: Orientalism, Feminism, and Popular Culture by Jennifer Lynn Haynes-Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Michele R. Gamburd, Chair Sharon A. Carstens Priya Kandaswamy Portland State University ©2010 Abstract Belly dance classes have become increasingly popular in recent decades in the United States. Many of the predominantly white, middle-class American women who belly dance proclaim that it is a source of feminist identity and empowerment that brings deeper meaning to their lives. American practitioners of this art form commonly explain that it originated from ritual-based dances of ancient Middle Eastern cultures and regard their participation as a link in a continuous lineage of female dancers. -

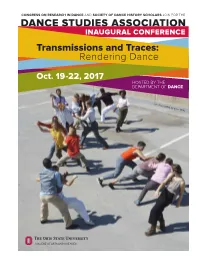

Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance

INAUGURAL CONFERENCE Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance Oct. 19-22, 2017 HOSTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE Sel Fou! (2016) by Bebe Miller i MAKE YOUR MOVE GET YOUR MFA IN DANCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN We encourage deep engagement through the transformative experiences of dancing and dance making. Hone your creative voice and benefit from an extraordinary breadth of resources at a leading research university. Two-year MFA includes full tuition coverage, health insurance, and stipend. smtd.umich.edu/dance CORD program 2017.indd 1 ii 7/27/17 1:33 PM DEPARTMENT OF DANCE dance.osu.edu | (614) 292-7977 | NASD Accredited Congratulations CORD+SDHS on the merger into DSA PhD in Dance Studies MFA in Dance Emerging scholars motivated to Dance artists eager to commit to a study critical theory, history, and rigorous three-year program literature in dance THINKING BODIES / AGILE MINDS PhD, MFA, BFA, Minor Faculty Movement Practice, Performance, Improvisation Susan Hadley, Chair • Harmony Bench • Ann Sofie Choreography, Dance Film, Creative Technologies Clemmensen • Dave Covey • Melanye White Dixon Pedagogy, Movement Analysis Karen Eliot • Hannah Kosstrin • Crystal Michelle History, Theory, Literature Perkins • Susan Van Pelt Petry • Daniel Roberts Music, Production, Lighting Mitchell Rose • Eddie Taketa • Valarie Williams Norah Zuniga Shaw Application Deadline: November 15, 2017 iii DANCE STUDIES ASSOCIATION Thank You Dance Studies Association (DSA) We thank Hughes, Hubbard & Reed LLP would like to thank Volunteer for the professional and generous legal Lawyers for the Arts (NY) for the support they contributed to the merger of important services they provide to the Congress on Research in Dance and the artists and arts organizations. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 The Cascading Effect: Mitigating the Effects of Choking under Pressure in Dancers Ashley Marie Fryer Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE CASCADING EFFECT: MITIGATING THE EFFECTS OF CHOKING UNDER PRESSURE IN DANCERS By ASHLEY MARIE FRYER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Psychology and Learning Systems in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Ashley Marie Fryer defended this dissertation on May 3, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Gershon Tenenbaum Professor Directing Dissertation Susan K. Blessing University Representative Graig M. Chow Committee Member Thomas Welsh Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I would like to dedicate this thesis to Ryan Sides and my family for their love and support that is unparalleled. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to acknowledge Jody Isenhour and Doubletake Dance for their tireless efforts to help me in data collection. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. -

LINDA CARUSO HAVILAND Dance Program Bryn Mawr College 101

v LINDA CARUSO HAVILAND v Dance Program August 2018 Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr, PA 19010 [email protected] vv indicates entries prior to 2010 EDUCATION 1995 Ed.D. Department of Dance, Temple University, Philadelphia Dissertation: "Dancing at the Juncture of Being and Knowing: Sartrean Ontology, Embodiment, Gender and Dance." [Committee: Ferdun (Dance), M. Beardsley (Philosophy), J. Margolis (Philosophy) J. Immerwahr (Philosophy), S. Hilsendager (Dance)] • Recipient: Teaching Associate position 1972 M.Ed. Department of Dance, Temple University, Philadelphia Choreographic Thesis Project: Landscape with the Fall of Icarus • Recipient: Graduate Assistantship position 1971 B.A. Department of Dance, Adelphi University, Garden City • Magna cum laude, Dean's List, Departmental Honors 2003 Liz Lerman’s Critical Response training, Dance Exchange, Takoma Park, MD 1975 Dance Criticism--Jack Anderson, Robert Pierce, Kathy Duncan (semester course , New School for Social Research, NYC) 1974 Dance Criticism--Deborah Jowitt, Marcia Siegel (eight week intensive, NYC) 1973 Aesthetics—(semester course at New School for Social Research, NYC) 1973 Dance Aesthetics--Selma Jean Cohen (six week intensive, NYC) PRINCIPLE D ANCE TECHNIQUE AND PERFORMANCE TRAINING 2010- Gaga: Idan Porges, Modern Dance: Becky Malcolm-Naib, Eun Jung Choi, K.C. Chun Manning, Scott McPheeters, Rhonda Moore and ongoing master classes/workshops with visiting artists Prior to 2010 Intensive study with: Hellmut Gottschild, Karen Bamonte, Eva Gholson, Pat Thomas, -

Dance As a Cultural Element in Spain and Spanish America

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) Honors Program 1992 Dance as a cultural element in Spain and Spanish America Amy Lynn Wall University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1992 Amy Lynn Wall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wall, Amy Lynn, "Dance as a cultural element in Spain and Spanish America" (1992). Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006). 151. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst/151 This Open Access Presidential Scholars Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dance as Cultural Element 1 Dance as a Cultural Element in Spain and Spanish America Amy Lynn Wall University of Northern Iowa Submitted in partial completion of University of Northern Iowa Presidential Scholars Board and Scholarship requirements. Submitted the 6th day of May, 1992 A.O. Running head: Dance as a Cultural Element Dance as Cultural Element 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 History 4 Purpose of Dance 1 0 Recent Dance Styles 1 3 Northern Provinces l 8 Pais Vasco 21 Mediterranean Provinces 28 Central Plateau Provinces 30 Southern Region 33 Liturgical Dance 37 Gypsy Culture 43 Spanish Influence m America 46 Uruguay 47 Argentina 50 Central America 53 Discussion 54 Conclusion 55 Bibliography 57 Appendices A-Glossary of Names and Places 6 3 B-Glossary of Dance, Music, Instruments 7 0 Continental Maps 7 6 Dance as Cultural Element 3 Dance, a performing and recreational art throughout the world, plays an important role in Spanish and Hispanic culture. -

Working Women and Dance in Progressive Era New York City, 1890-1920 Jennifer L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Working Women and Dance in Progressive Era New York City, 1890-1920 Jennifer L. Bishop Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE WORKING WOMEN AND DANCE IN PROGRESSIVE ERA NEW YORK CITY, 1890-1920 By JENNIFER L. BISHOP A Thesis submitted to the Department of Dance In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2003 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jennifer L. Bishop defended on June 06, 2003. ____________________ Tricia Young Chairperson of Committee ____________________ Neil Jumonville Committee Member ____________________ John O. Perpener, III. Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Some of the ideas presented in this thesis are inspired by previous coursework. I would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Neil Jumonville’s U.S. Intellectual History courses and Dr. Sally Sommer’s American Dance History courses in influencing my approach to this project. I would also like to acknowledge the editorial feedback from Dr. Tricia Young. Dr. Young’s comments have encouraged me to synthesize this material in creative, yet concise methods. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..…v INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….……… 1 1. REFORMING AMERICA: Progressive Era New York City as Context for Turn-of-the-Century American Dance…………………………………………….6 2. VICE AND VIRTUE: The Competitive Race to Shape American Identities Through Leisure and Vernacular Dance Practices…………………….………31 3. -

Sabbatical Report / Fall 2019 Meghan Cardwell-Wilson, Professor of Dance Acknowledgements

Sabbatical Report / Fall 2019 Meghan Cardwell-Wilson, Professor of Dance Acknowledgements: I extend a sincere thank you to Dr. Matkin, the Board of Trustees, the Sabbatical Leave Committee, Dr. Weasenforth, Dr. Gunderson, and Dr. Tinnen for the opportunity to take a sabbatical leave in Fall 2019. Sabbatical Purpose: The primary purpose of this sabbatical was to research global perspectives in dance that extend beyond my current expertise in Western dance forms. As the sole full-time Dance Professor at the Frisco Campus, it is my responsibility to share a comprehensive understanding of dance with students. However, there was, and will always be, room for me to better fulfill this responsibility. My dancing body is the product of a Western education that often upholds ballet and modern as the pillars of dance. While I have long conducted research via scholarly readings on global dance forms and engaged in an occasional dance studio class that is non-Western, this sabbatical was a necessary step toward focused embodiment of global dance forms. Sabbatical Summary: I began sabbatical by enrolling in a weekly Bharatanatyam dance studio class taught by Sarita Venkatraman of Arathi School of Dance. I also audited the 16-week Dance & Globalization (DNCE 2143) dance studio course at Texas Woman’s University, and the six-week Dance History: Global, Cultural, and Historical Considerations course through the National Dance Education Organization (NDEO) Online Professional Development Institute (OPDI). Additional sabbatical activities included attending the Women in Dance Leadership Conference in Philadelphia, PA and conducting selected readings on global perspectives in dance. Studying Bharatanatyam, one of the eight classical dances of India, was part of my original sabbatical plan, as was enrolling in the Dance & Globalization course at TWU. -

With Intention: Triumphs & Challenges in Canadian Dance/Movement

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMf WITH INTENTION: TRIUMPHS & CHALLENGES IN CANADIAN DANCE/MOVEMENT THERAPY ANDREAH BARKER A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Dance York University Toronto, Ontario June 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53654-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53654-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.