2013-07-08-Security Researchers Amicus.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6w76f8x7 Author Swift, Kathy Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Kathleen Anne Swift Committee in charge: Professor Richard Duran, Chair Professor Diana Arya Professor William Robinson September 2017 The dissertation of Kathleen Anne Swift is approved. ................................................................................................................................ Diana Arya ................................................................................................................................ William Robinson ................................................................................................................................ Richard Duran, Committee Chair June 2017 A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Copyright © 2017 by Kathleen Anne Swift iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their advice and patience as I worked on gathering and analyzing the copious amounts of research necessary to -

ROADS and BRIDGES: the UNSEEN LABOR BEHIND OUR DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE Preface

Roads and Bridges:The Unseen Labor Behind Our Digital Infrastructure WRITTEN BY Nadia Eghbal 2 Open up your phone. Your social media, your news, your medical records, your bank: they are all using free and public code. Contents 3 Table of Contents 4 Preface 58 Challenges Facing Digital Infrastructure 5 Foreword 59 Open source’s complicated relationship with money 8 Executive Summary 66 Why digital infrastructure support 11 Introduction problems are accelerating 77 The hidden costs of ignoring infrastructure 18 History and Background of Digital Infrastructure 89 Sustaining Digital Infrastructure 19 How software gets built 90 Business models for digital infrastructure 23 How not charging for software transformed society 97 Finding a sponsor or donor for an infrastructure project 29 A brief history of free and public software and the people who made it 106 Why is it so hard to fund these projects? 109 Institutional efforts to support digital infrastructure 37 How The Current System Works 38 What is digital infrastructure, and how 124 Opportunities Ahead does it get built? 125 Developing effective support strategies 46 How are digital infrastructure projects managed and supported? 127 Priming the landscape 136 The crossroads we face 53 Why do people keep contributing to these projects, when they’re not getting paid for it? 139 Appendix 140 Glossary 142 Acknowledgements ROADS AND BRIDGES: THE UNSEEN LABOR BEHIND OUR DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE Preface Our modern society—everything from hospitals to stock markets to newspapers to social media—runs on software. But take a closer look, and you’ll find that the tools we use to build software are buckling under demand. -

Security Now! #731 - 09-10-19 Deepfakes

Security Now! #731 - 09-10-19 DeepFakes This week on Security Now! This week we look at a forced two-day recess of all schools in Flagstaff, Arizona, the case of a Ransomware operator being too greedy, Apple's controversial response to Google's posting last week about the watering hole attacks, Zerodium's new payout schedule and what it might mean, the final full public disclosure of BlueKeep exploitation code, some potentially serious flaws found and fixed in PHP that may require our listener's attention, some SQRL news, miscellany, and closing-the-loop feedback from a listener. Then we take our first look on this podcast into the growing problem and threat of "DeepFake" media content. All Flagstaff Arizona Schools Cancelled Thursday, August 5th And not surprisingly, recess is extended through Friday: https://www.fusd1.org/facts https://www.facebook.com/FUSD1/ And Saturday... Security Now! #730 1 And Sunday... Security News A lesson for greedy ransomware: Ask for too much… and you get nothing! After two months of silence, last Wednesday Mayor Jon Mitchell of New Bedford, Massachusetts held their first press conference to tell the interesting story of their ransomware attack... The city's IT network was hit with the Ryuk (ree-ook) ransomware which, by the way, Malwarebytes now places at the top of the list of file-encrypting malware targeting businesses. It'll be interesting to see whether So-Dino-Kee-Bee's affiliate marketing model is able to displace Ryuk. But, in any event, very fortunately for the city of New Bedford, hackers breached the city's IT network and got Ryuk running in the wee hours of the morning following the annual 4th of July holiday. -

Security Applications of Formal Language Theory

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Computer Science Technical Reports Computer Science 11-25-2011 Security Applications of Formal Language Theory Len Sassaman Dartmouth College Meredith L. Patterson Dartmouth College Sergey Bratus Dartmouth College Michael E. Locasto Dartmouth College Anna Shubina Dartmouth College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/cs_tr Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Sassaman, Len; Patterson, Meredith L.; Bratus, Sergey; Locasto, Michael E.; and Shubina, Anna, "Security Applications of Formal Language Theory" (2011). Computer Science Technical Report TR2011-709. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/cs_tr/335 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Science Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Security Applications of Formal Language Theory Dartmouth Computer Science Technical Report TR2011-709 Len Sassaman, Meredith L. Patterson, Sergey Bratus, Michael E. Locasto, Anna Shubina November 25, 2011 Abstract We present an approach to improving the security of complex, composed systems based on formal language theory, and show how this approach leads to advances in input validation, security modeling, attack surface reduction, and ultimately, software design and programming methodology. We cite examples based on real-world security flaws in common protocols representing different classes of protocol complexity. We also introduce a formalization of an exploit development technique, the parse tree differential attack, made possible by our conception of the role of formal grammars in security. These insights make possible future advances in software auditing techniques applicable to static and dynamic binary analysis, fuzzing, and general reverse-engineering and exploit development. -

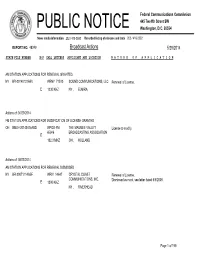

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: an Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri, St. Louis University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 11-22-2005 Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Holt, Thomas Jeffrey, "Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers" (2005). Dissertations. 616. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/616 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers by THOMAS J. HOLT M.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2003 B.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2000 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI- ST. LOUIS In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Criminology and Criminal Justice August, 2005 Advisory Committee Jody Miller, Ph. D. Chairperson Scott H. Decker, Ph. D. G. David Curry, Ph. D. Vicki Sauter, Ph. D. Copyright 2005 by Thomas Jeffrey Holt All Rights Reserved Holt, Thomas, 2005, UMSL, p. -

The Quality Attribute Design Strategy for a Social Network Data Analysis System

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-2016 The Quality Attribute Design Strategy for a Social Network Data Analysis System Ziyi Bai [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Bai, Ziyi, "The Quality Attribute Design Strategy for a Social Network Data Analysis System" (2016). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Quality Attribute Design Strategy for a Social Network Data Analysis System by Ziyi Bai A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Software Engineering Supervised by Dr. Scott Hawker Department of Software Engineering B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, New York May 2016 ii The thesis “The Quality Attribute Design Strategy for a Social Network Data Analy- sis System” by Ziyi Bai has been examined and approved by the following Examination Committee: Dr. Scott Hawker Associate Professor Thesis Committee Chair Dr. Christopher Homan Associate Professor Dr. Stephanie Ludi Professor iii Acknowledgments Dr.Scott Hawker, I can confidently state that without your guidance I would not have accomplished my achievement. Your support has impacted my future for the better. Thank you for everything. Dr. Chris Homan, I am so thankful that you reached out to me and provided the requirements for this thesis. -

Coleman-Coding-Freedom.Pdf

Coding Freedom !" Coding Freedom THE ETHICS AND AESTHETICS OF HACKING !" E. GABRIELLA COLEMAN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2013 by Princeton University Press Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs CC BY- NC- ND Requests for permission to modify material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved At the time of writing of this book, the references to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate. Neither the author nor Princeton University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, E. Gabriella, 1973– Coding freedom : the ethics and aesthetics of hacking / E. Gabriella Coleman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-14460-3 (hbk. : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-691-14461-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Computer hackers. 2. Computer programmers. 3. Computer programming—Moral and ethical aspects. 4. Computer programming—Social aspects. 5. Intellectual freedom. I. Title. HD8039.D37C65 2012 174’.90051--dc23 2012031422 British Library Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 This book is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE !" We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it. -

Lower Hudson Valley

NY STATE EAS MONITORING ASSIGNMENTS - REGION 14 - LOWER HUDSON VALLEY Region 14 - Lower Hudson Valley Counties of: Orange, Putnam, Lower Hudson Valley, Rockland, Westchester Callsign Frequency City of License Monitor 1 Monitor 2 SR/LP1 WHUD 100.7 mHz. Peekskill WABC WPDH SR/LP1 WLNA 1420 kHz. Peekskill WABC WPDH LP1 WFAS 1230 kHz. White Plains WHUD WABC LP1 WNBMFM 103.9 mHz. Bronxville WCBS WABC LP1 WJGK 103.1 mHz. Newburgh WHUD WFGB LP2 WOSR 91.7 mHz. Middletown WHUD WJGK LP2 WRPJ 88.9 MHz Port Jervis WPDH WAMCFM PN WALL 1340 kHz. Middletown WPDH WRPJ PN WANR 88.5 MHz Brewster WJGK WHUD PN WARY 88.1 mHz. Valhalla WHUD WNBMFM PN WDBY 105.5 mHz. Patterson WHUD WNBMFM PN WDLC 1490 kHz. Port Jervis WPDH WRPJ pPN WEPTCD 22 Newburgh WHUD WJGK PN WFME 106.3 mHz. Mount Kisco WHUD WKLVFM PN WGNY 1220 kHz. Newburgh WHUD WFGB PN WJZZ 90.1 mHz. Montgomery WPDH WRPJ PN WARW 96.7 MHz Port Chester WNBMFM WNYCFM PN WLJP 89.3 mHz. Monroe WPDH WAMCFM PN WMFU 90.1 mHz. Mount Hope WHUD WJGK PN WNYK 88.7 MHz Nyack WHUD WNBMFM PN WNYX 88.1 mHz. Montgomery WJGK WHUD PN WOSS 91.1 MHz Ossining WFASFM WHUD PN WPUT 1510 kHz. North Salem WHUD WNBMFM PN WQXW 90.3 mHz. Ossining WNYCFM WABC PN WRCR 1700 kHz Ramapo WHUD WOSS PN WRKL 910 kHz. New City WHUD WNBMFM PN WRRV 92.7 MHz Middletown WHUD WJGK PN WRVP 1310 kHz Mount Kisco WABC WNYCFM PN WSPK 104.7 MHz Poughkeepsie WPDH WFGB PN WTBQ 1110 kHz. -

Scada & Plc Vulnerabilities in Correctional Facilities

SCADA & PLC VULNERABILITIES IN CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES White Paper Teague Newman Tiffany Rad, ELCnetworks, LLC John Strauchs, Strauchs, LLC 7/30/2011 © 2011 Newman, Rad, Strauchs PLC Vulnerabilities in Correctional Facilities Newman, Rad, Strauchs Abstract On Christmas Eve not long ago, a call was made from a prison warden: all of the cells on death row popped open. Not sure how or if it could happen again, the prison warden requested security experts to investigate. Many prisons and jails use SCADA systems with PLCs to open and close doors. As a result of Stuxnet academic research, we have discovered significant vulnerabilities in PLCs used in correctional facilities by being able to remotely flip the switches to “open” or “locked closed” on cell doors and gates. Using original and publically available exploits along with evaluating vulnerabilities in electronic and physical security designs, we will analyze SCADA systems and PLC vulnerabilities in correctional and government secured facilities while making recommendations for improved security measures. 1 PLC Vulnerabilities in Correctional Facilities Newman, Rad, Strauchs Biographies John J. Strauchs, M.A., C.P.P., conducted the security engineering or consulting for more than 114 justice design (police, courts, and corrections) projects in his career, which included 14 federal prisons, 23 state prisons, and 27 city or county jails. He owned and operated a professional engineering firm, Systech Group, Inc., for 23 years and is President of Strauchs, LLC. He was an equity principal in charge of security engineering for Gage-Babcock & Associates and an operations officer with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). His company and work was an inspiration for the 1993 movie, “Sneakers” for which he was the Technical Advisor. -

Lower Hudson Valley

NY STATE EAS MONITORING ASSIGNMENTS - REGION 14 - LOWER HUDSON VALLEY Region 14 - Lower Hudson Valley Counties of: Orange, Putnam, Lower Hudson Valley, Rockland, Westchester Callsign Frequency City of License Monitor 1 Monitor 2 SR/LP1 WHUD 100.7 mHz. Peekskill WABC WPDH SR/LP1 WLNA 1420 kHz. Peekskill WABC WPDH LP1 WFAS 1230 kHz. White Plains WHUD WABC LP1 WNBMFM 103.9 mHz. Bronxville WCBS WABC LP1 WJGK 103.1 mHz. Newburgh WHUD WFGB LP2 WOSR 91.7 mHz. Middletown WHUD WJGK LP2 WRPJ 88.9 MHz Port Jervis WPDH WAMCFM PN WALL 1340 kHz. Middletown WPDH WRPJ PN WANR 88.5 MHz Brewster WJGK WHUD PN WARY 88.1 mHz. Valhalla WHUD WNBMFM PN WDBY 105.5 mHz. Patterson WHUD WNBMFM PN WDLC 1490 kHz. Port Jervis WPDH WRPJ pPN WEPTCD 22 Newburgh WHUD WJGK PN WFME 106.3 mHz. Mount Kisco WHUD WKLVFM PN WGNY 1220 kHz. Newburgh WHUD WFGB PN WJZZ 90.1 mHz. Montgomery WPDH WRPJ PN WARW 96.7 MHz Port Chester WNBMFM WNYCFM PN WLJP 89.3 mHz. Monroe WPDH WAMCFM PN WMFU 90.1 mHz. Mount Hope WHUD WJGK PN WNYK 88.7 MHz Nyack WHUD WNBMFM PN WNYX 88.1 mHz. Montgomery WJGK WHUD PN WOSS 91.1 MHz Ossining WFASFM WHUD PN WPUT 1510 kHz. North Salem WHUD WDBY PN WQXW 90.3 mHz. Ossining WNYCFM WABC PN WRCR 1700 kHz Ramapo WHUD WOSS PN WRKL 910 kHz. New City WHUD WNBMFM PN WRRV 92.7 MHz Middletown WHUD WJGK PN WRVP 1310 kHz Mount Kisco WABC WNYCFM PN WSPK 104.7 MHz Poughkeepsie WPDH WFGB PN WTBQ 1110 kHz. -

Group Project

Awareness & Prevention of Black Hat Hackers Mohamed Islam & Yves Francois IASP 470 History on Hacking • Was born in MIT’s Tech Model Railway Club in 1960 • Were considered computer wizards who had a passion for exploring electronic systems • Would examine electronic systems to familiarize themselves with the weaknesses of the system • Had strict ethical codes • As computers became more accessible hackers were replaced with more youthful that did not share the same ethical high ground. Types of Hackers • Script Kiddie: Uses existing computer scripts or code to hack into computers usually lacking the expertise to write their own. Common script kiddie attack is DoSing or DDoSing. • White Hat: person who hacks into a computer network to test or evaluate its security system. They are also known as ethical hackers usually with a college degree in IT security. • Black Hat: Person who hacks into a computer network with malicious or criminal intent. • Grey Hat: This person falls between white and black hat hackers. This is a security expert who may sometimes violate laws or typical ethical standards but does not have the malicious intent associated with a black hat hacker. • Green Hat: Person who is new to the hacking world but is passionate about the craft and works vigorously to excel at it to become a full-blown hacker • Red Hat: Security experts that have a similar agenda to white hat hackers which is stopping black hat hackers. Instead of reporting a malicious attack like a white hat hacker would do they would and believe that they can and will take down the perpretrator.