ASJ 2000.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 29 September 2004 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074, Ph. 07-3279 2279, E-mail: [email protected] 29.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 30 November 2004. Send copy to acting editor, Victor Isaacs at <[email protected]> or post to 43 Lowanna St, Braddon, ACT, 2612. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link from the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/journ-comm/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/ Barry Blair, of Tamworth, NSW, and Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, are major contributors to this Newsletter. Two books published this month by the Australian Newspaper History Group – See Page 20 CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 29.2 THE AUSTRALIAN AT 40 (see also 28.2) The Weekend Australian of 17-18 July 2004 followed up the editorial that appeared on the Australian’s 40th birthday (15 July) with another about the newspaper (“For the nation’s newspaper, life begins at 40”), probably largely because the readership of the weekend edition is much greater than that of the weekday issues. The editorial says, in part: “In an age where many so-called quality newspapers emphasise the fripperies of fashion – there is an endless obsession with lifestyle over substance in our rivals – the Australian remains true to its original mission. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

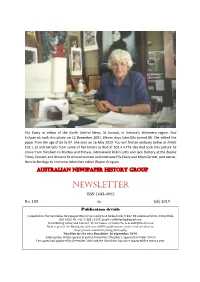

Ella Ebery as editor of the North Central News, St Arnaud, in Victoria’s Wimmera region. Rod Kirkpatrick took this photo on 12 December 2001. Eleven days later Ella turned 86. She edited the paper from the age of 63 to 97. She died on 16 May 2019. You will find an obituary below at ANHG 103.1.13 and extracts from some of her letters to Rod at 103.4.4.The day Rod took this picture he drove from Horsham to Murtoa and Minyip, interviewed Robin Letts and Jack Slattery at the Buloke Times, Donald, and drove to St Arnaud to meet and interview Ella Ebery and Brian Garrett, part owner, then to Bendigo to interview Advertiser editor Wayne Gregson. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 103 m July 2019 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2019. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan Index to issues 1-100: thanks Thank you to the subscribers who contributed to the appeal for $650 to help fund the index to issues 76 to 100 of the ANHG Newsletter, with the index to be incorporated in a master index covering Nos. -

Annual Report 2012

NEWS CORP. ANNU AL REPO RT 2012 NEWSANNUAL REPORT 2012 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10036 www.newscorp.com C O RP. 425667.COVER.CX.CS5.indd 1 8/29/12 5:21 PM OUR AIM IS TO UNLOCK MORE VALUE FOR OUR STOCKHOLDERS 425667.COVER.CS5.indd 2 8/31/12 9:58 AM WE HAVE NO INTENTION OF RESTING ON OUR LAURELS WE ARE ALWAYS INVESTING IN THE NEXT GENERATION 425667.TEXT.CS5.indd 2 8/28/12 5:10 PM 425667.TEXT.CS5.indd 3 8/27/12 8:44 PM The World’s LEADER IN QUALITY JOURNALISM 425667.TEXT.CS5.indd 4 8/28/12 5:11 PM A LETTER FROM Rupert Murdoch It takes no special genius to post good earnings in a booming economy. It’s the special company that delivers in a bad economic environment. At a time when the U.S. has been weighed down by its slowest recovery since the Great Depression, when Europe’s currency threatens its union and, I might add when our critics flood the field with stories that refuse to move beyond the misdeeds at two of our papers in Britain, I am delighted to report something about News Corporation you Rupert Murdoch, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer might not know from the headlines: News Corporation In 2012, for the second year in a row, we have brought our stockholders double-digit growth in total segment operating income. FOR THE SECOND We accomplished this because we do not consider ourselves a conventional YEAR IN A ROW, company. -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Tuesday, 18 September 2012

Article No. 7135 Available on www.roymorgan.com Link to Roy Morgan Profiles Thursday, 9 February 2017 Digital audience growth continued to drive newspaper readership higher in 2016 Roy Morgan Research today releases the latest Print Readership and Cross-Platform Audience results for Australian Newspapers for the 12 months to December 2016. Alongside a number of success stories in print, just over half of mastheads increased their total E cross-platform reach compared with the previous results to September 2016—and readership via websites and apps was again the driving force behind that growth. Print Readership Highlights 8,153,000 million Australians aged 14+ (41 percent) read print newspapers in an average week in 2016. This is down 4.3 percent, or just over half a million readers, compared with 2015. Appetite for print news continues to hold strongest on Saturdays. 4.9 million read Saturday print newspapers in an average week (down 2.7 percent). Sunday titles reach 4.4 million (down 4.3 percent), and Monday to Friday dailies reach a combined 5.7 million readers during the week (down 4.8 percent). Readers return to weekday national titles News Corp’s and Fairfax’s national titles have both gained weekday readers. The Australian is up 8.0 percent year-on-year, with 336,000 readers per average Monday to Friday issue in 2016— 25,000 more than in 2015. The Australian Financial Review is up 3.1 percent to 201,000 readers. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEAS Melbourne vs Sydney The Daily Telegraph and Herald Sun each continued to post strong readership results in print on weekdays and Saturdays. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 37 May 2006 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074. Ph. 07-3279 2279. E-mail: [email protected] 37.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 15 July 2006. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/journ-comm/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/) CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 37.2 MEDIA REFORM PROPOSALS Communications Minister Helen Coonan issued on 14 March an outline of proposals to reform Australia’s media laws. She wanted feedback from stakeholders by 18 April. Under the proposals, newspaper groups and radio groups could be acquired by free-to-air TV networks and vice-versa – and so, Nine, for instance, could buy John Fairfax Holdings, and News Ltd could buy Channel 10. Free-to-air channels would face competition from emerging digital TV players. Senator Coonan said the cross-media and foreign ownership restrictions would be removed by 2007 or 2012, but the Government would require at least five “commercial media groups” to remain in metropolitan markets and four in regional markets. Extensive coverage of the Coonan proposals was provided in, for example, the Australian of 15 March (pp.1, 6, 7, 13, 31, 34) and 16 March (pp.2, 14, 17, 19, 22 and 25) and the Australian Financial Review of 15 March (pp.1, 11, 14, 28, 47, 48, 49, 57, 59 and 60). -

Apo-Nid63005.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1991-92 Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Sydney 1992 ©Commonwealth of Australia ISSN 0728-8883 Design by Media and Public Relations Branch, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. Printed in Australia by Pirie Printers Sales Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.CT. 11 Contents 1. MEMBERSIDP OF THE TRIBUNAL 1 2. THE YEAR IN REVIEW 7 3. POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE TRIBUNAL 13 Responsible Minister 16 4. LICENSING 17 Number and Type of Licences on Issue 19 Grant of Limited Licences 20 Commercial Radio Licence Grant Inquiries 21 Supplementary Radio Grant Inquiries 23 Joined Supplementary /Independent Radio Grant Inquiries 24 Remote Licences 26 Public Radio Licence Grants 26 Renewal of Licences with Conditions or Licensee Undertaking 30 Revocation/Suspension/Conditions Inquiries 32 Allocation of Call Signs 37 5. OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL 39 Applications and Notices Received 41 Most Significant Inquiries 41 Unfinished Inquiries 47 Contraventions Amounting To Offences 49 Licence Transfers 49 Uncompleted Inquiries 50 Operation of Service by Other than Licensee 50 Registered Lender and Loan Interest Inquiries 50 6. PROGRAM AND ADVERTISING STANDARDS 51 Program and Advertising Standards 53 Australian Content 54 Compliance with Australian Content Television Standard 55 Children's Television Standards 55 Compliance with Children's Standards 58 Comments and Complaints 59 Broadcasting of Political Matter 60 Research 61 iii 7. PROGRAMS - PUBLIC INQUIRIES 63 Public Inquiries 65 Classification of Television Programs 65 Foreign Content In Television Advertisements 67 Advertising Time On Television 68 Film And Television Co-productions 70 Australian Documentary Programs 71 Cigarette Advertising During The 1990 Grand Prix 72 Test Market Provisions For Foreign Television Advertisements 72 Public Radio Sponsorship Announcements 73 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 74 John Laws - Comments About Aborigines 75 Anti-Discrimination Standards 75 Accuracy & Fairness in Current Affairs 76 Religious Broadcasts 77 Review of Classification Children's Television Programs 78 8. -

West Coast Council, Zeehan Landfill Wetlands, Extension

Environmental Assessment Report Zeehan Landfill Wetland Zeehan Waste Depot, Zeehan West Coast Council July 2021 Environmental Assessment Report – West Coast Council – Zeehan Landfill Wetland, Zeehan Waste Depot, Zeehan 1 Environmental Assessment Report Proponent West Coast Council Proposal Zeehan Landfill Wetland Location Zeehan Waste Depot, 3990 Henty Road, Zeehan Tasmania 7467 NELMS no. PCE 10460 Permit Application No. 2021/13 West Coast Council Electronic Folder No. EN-EM-EV-DE 261742-001 Document No. D21-26020 Class of Assessment 2A Assessment Process Milestones 25 May 2020 Notice of Intent lodged 01 July 2020 Guidelines Issued 02 March 2021 Permit Application submitted to Council 03 March 2021 Application received by the Board 13 March 2021 Start of public consultation period 27 March 2021 End of public consultation period 6 May 2021 Date draft conditions issued to proponent 7 May 2021 Statutory period for assessment ends, extension agreed until 21 May 2021 21 May 2021 Proponent submits amended layout to EPA with amended activity area and prepares to submit Permit Application. 12 June 2021 Start of public consultation period 26 June 2021 End of public consultation period 6 May 2021 Conditions forwarded to proponent for comment Environmental Assessment Report – West Coast Council – Zeehan Landfill Wetland, Zeehan Waste Depot, Zeehan 2 Acronyms 7Q10 Lowest 7 day average flow in a 10 year period AMD Acid and Metalliferous Drainage AMDMP Acid and Metalliferous Drainage Management Plan AMT Accepted Modern Technology ANZECC Guidelines Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality 2000 (co published by the Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council). -

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

2020 N'letter July.Aug

DUBBO & DISTRICT FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INC Newsletter 49 – July-August 2020 (Another Covid-19 issue) Location: Ground floor – Two storey Community Arts Building Western Plains Gallery, Cnr. Gipps and Wingewarra Streets, Dubbo. Opening hours: Tuesday 1.00-4pm, Thursday 2.00-6.00pm, Friday 10.00-1.00pm, Saturday 10.00-4.00pm Society webpage: www.dubbofamilyhistory.org.au Society email: [email protected] Postal address: PO Box 868, Dubbo. 2830 NSW Society phone no: 02 6881 8635 (during opening hours) Management Committee Linda Barnes 68878284 [email protected] President/Librarian Lyn Smith 68850107 [email protected] Vice President Ken Fuller 68818128 [email protected] Treasurer Robyn Allan 68844572 [email protected] Minute Secretary June Wilson 68825366 [email protected] Karlyn Robinson 68855773 [email protected] Kathy Furney 68825533 [email protected] Newsletter Lesley Abrahams 68822242 [email protected] Management Committee Meets on the 2nd Thursday of the month at 10am in DDFHS Library. Members are welcome to attend these meetings, or simply contact any of the committee listed above if you have anything you would like discussed at the meeting. No meetings currently being held during Covid- 19 pandemic. Newsletter Information Please share any interesting information, news of an interesting website, or maybe a breakthrough with your family history, with other members. Contact Kathy Ph.0427 971 232 or email [email protected] if you have anything that can be shared. We would love to print your item as it is exciting to hear about our members’ research. Website and Facebook Check out the website and Facebook regularly as there is often useful information on them. -

The Byron Shire Echo

OPEN FOR BUSINESS SINCE 1986! LONG LIVE THE PRINTED REALM The Byron Shire Echo • Volume 34 #52 • Wednesday, June 3, 2020 • www.echo.net.au News Corp scraps print Finally – table service! for paid online subs Mandy Nolan ‘I guess there had been talk here and there that papers were dying From June 29, nearly 100 regional and digital subscriptions were the newspapers, owned by US citizen latest, but we absolutely didn’t see and multi-billionaire Rupert Mur- this coming’. doch, will cease print operations. Another employee, who wished News Corp announced they will to also remain anonymous, is a move the (mostly free) titles to single parent. They said, ‘I felt like behind an online paywall. my job was secure. I had a car loan, Locally this includes the Byron a personal loan and I live alone. It News, the Northern Star, the Ballina will impact me heavily. I don’t know Advocate and the Tweed Daily News. if I can get another job, or if I have to Some communities will now be move in with my mum.’ without a local newspaper for the first time in generations. Politicians only winners A longtime journalist for a local from the decision News Corp newspaper, who asked to remain anonymous, said, ‘What hap- Both Tania and her colleagues pens when a local paper disappears? believe that many in the community Whether paid or free, the common will struggle with a digital format. thread is lost – communities lose a ‘The older demographic will point of connection for finding out definitely struggle without a print anything; from the most mundane version. -

“Win Your Dad a Landboss for Father's Day” Promotion Terms & Conditions

“Win your Dad a Landboss for Father's Day” Promotion Terms & Conditions 1. Information on how to enter and the prize forms part of these conditions. By participating, entrants agree to be bound by these conditions. Entries must comply with these conditions to be valid. 2. Entry is only open to Australian residents of WA, VIC, NSW, QLD & SA who are over the age of 18 years. Employees (and their immediate families) of the Promoter and agencies associated with this promotion are ineligible to enter. 3. To enter: Readers will enter a photograph of their father, stating in 25 words or less, why their Dad is the best, to go into the running to win a Landboss UTV valued at $15,990 RRP. A. The photograph needs to be entered on the “Win Your Dad a Landboss for Father’s Day Competition Page” This page is accessible from all participating publication websites. B. As the competition progresses, an online gallery of the best entries will appear on the “Win Your Dad a Landboss for Father’s Day Competition Page” on the promoters websites. C. Images will be vetted by the Promoter before being uploaded to this Gallery. D. Entrants must adhere to the mechanism of the promotion as may be briefed and communicated to the Clients by the Promoter during the Promotional Period. E. Only 1 entry per Entrant is permitted. F. Entrants must have the photographer's and subject’s permission to enter the photograph and the photograph must be the original work of the photographer. 4. The promotion commences at 00.01 AEST on Thursday, 11 August 2016 and entries will be accepted until 23.59 AEST on 25 August 2016.