Clerical Continence in the Fourth Century: Three Papal Decretals Daniel Callam, C.S.B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Books List October-December 2011

New Books List October-December 2011 This catalogue of the Shakespeare First Folio (1623) is the result of two decades of research during which 232 surviving copies of this immeasurably important book were located – a remarkable 72 more than were recorded in the previous census over a century ago – and examined in situ, creating an essential reference work. ෮ Internationally renowned authors Eric Rasmussen, co-editor of the RSC Shakespeare series and Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, USA; Anthony James West, Shakespeare scholar, focused on the history of the First Folio since it left the press. ෮ Full bibliographic descriptions of each extant copy, including detailed accounts of press variants, watermarks, damage or repair and provenance ෮ Fascinating stories about previous owners and incidents ෮ Striking Illustrations in a colour plate section ෮ User’s Guide and Indices for easy cross referencing ෮ Hugely significant resource for researchers into the history of the book, as well as auction houses, book collectors, curators and specialist book dealers November 2011 | Hardback | 978-0-230-51765-3 | £225.00 For more information, please visit: www.palgrave.com/reference Order securely online at www.palgrave.com or telephone +44 (0)1256 302866 fax + 44(0)1256 330688 email [email protected] Jellybeans © Andrew Johnson/istock.com New Books List October-December 2011 KEY TO SYMBOLS Title is, or New Title available Web resource as an ebook Textbook comes with, a available CD-ROM/DVD Contents Language and Linguistics 68 Anthropology -

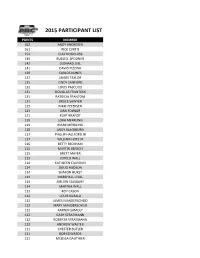

2015 Abcs Membersht.Csv

2015 PARTICIPANT LIST POINTS MEMBER 162 ANDY ANDRESEN 161 RICK CURTIS 152 CLAY DOUGLASS 145 RUSSELL SPOONER 142 LEONARD DILL 141 DAVID PIZZINO 139 CARLOS NUNES 137 JAMESTAYLOR 135 CINDY SANFORD 132 LOUIS PASCUCCI 131 DOUGLAS FRANTOM 131 PATRICIA FRANTOM 131 BRUCE SAWYER 125 NIKKI PETERSEN 123 DANFOWLER 121 KURT BRANDT 119 LORA MERKLING 119 MARK MERKLING 118 ANDY BLACKBURN 117 PHILLIP HALLFORD JR 117 WILLIAM HOTZ JR 116 BETTY BECKHAM 115 MARTIN BENSCH 115 BRETT MAYER 115 JEROLD WALL 114 KATHLEEN CALHOUN 114 DOUG HUDSON 114 SHARON HURST 114 MARSHALL LYALL 114 MELVIN SALSBURY 114 MARTHA WALL 113 ROY CASON 112 LOUIS KUBALA 112 JAMES MANDERSCHEID 112 MARY MANDERSCHEID 112 KAYREN SAMOLY 112 GARY STRATMANN 112 ROBERTA STRATMANN 112 ANDREW WALTER 111 CHESTER BUTLER 111 BOB EDWARDS 111 MELISSA GAUTHIER 111 LARRY LANGLINAIS 111 FREDERICK MCKAY 111 JAMES PIRTLE 111 THELMA PIRTLE 110 JOHN BRATSCHUN 110 NORMA EDWARDS 110 JEFF MCCLAIN 110 SANDRA MCCLAIN 110 MICHAEL PRITCHETT 110 CAROL TIMMONS 110 ROBERT TIMMONS 109 ERNEST STAPLES SR 108 BYRON CONSTANCE 108 ALFRED RATHBUN 107 WILLIAM BUSHALL JR 107 A CALVERT 107 JOHNKIME 107 KELLIE SALSBURY 106 MICHAEL ISEMAN 106 MONAOLSEN 106 THOMASOLSEN 106 SAMUEL STONE 106 JOHNTOOLE 105 VICTOR PONTE 104 PAUL CIPAR 104 DAVID THOMPSON 103 JOHN MCFADDEN 103 BENJAMIN PHILHOWER 103 SHERI PHILHOWER 103 BILL STOCK JR 103 MARTHA STOCK 102 GARY DYER 101 EDWARD GARBIN 101 TEDLAWSON 101 ROY STEPHENS JR 101 CLINT STOTT 100 JACK HARTLEY 100 PETER HULL 100 AARON KONECKY 100 DONNA LANDERS 100 GLEN LANDERS 100 DONSEPANSKI 99 CATHEY -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

ABSTRACT the Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories Of

ABSTRACT The Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret Scott A. Rushing, Ph.D. Mentor: Daniel H. Williams, Ph.D. This dissertation analyzes the transposition of the apostolic tradition in the fifth-century ecclesiastical histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. In the early patristic era, the apostolic tradition was defined as the transmission of the apostles’ teachings through the forms of Scripture, the rule of faith, and episcopal succession. Early Christians, e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen, believed that these channels preserved the original apostolic doctrines, and that the Church had faithfully handed them to successive generations. The Greek historians located the quintessence of the apostolic tradition through these traditional channels. However, the content of the tradition became transposed as a result of three historical movements during the fourth century: (1) Constantine inaugurated an era of Christian emperors, (2) the Council of Nicaea promulgated a creed in 325 A.D., and (3) monasticism emerged as a counter-cultural movement. Due to the confluence of these sweeping historical developments, the historians assumed the Nicene creed, the monastics, and Christian emperors into their taxonomy of the apostolic tradition. For reasons that crystallize long after Nicaea, the historians concluded that pro-Nicene theology epitomized the apostolic message. They accepted the introduction of new vocabulary, e.g. homoousios, as the standard of orthodoxy. In addition, the historians commended the pro- Nicene monastics and emperors as orthodox exemplars responsible for defending the apostolic tradition against the attacks of heretical enemies. The second chapter of this dissertation surveys the development of the apostolic tradition. -

THE EXEGETICAL ROOTS of TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY MICHAEL SLUSSER Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pa

Theological Studies 49 (1988) THE EXEGETICAL ROOTS OF TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY MICHAEL SLUSSER Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pa. N RECENT YEARS systematic theologians have been showing increased I interest in studying the doctrine of the Trinity. An integral part of that study should be an exposition of the origins of the doctrine. The question of origins can be posed in an analytical fashion, as Maurice Wiles has done: .. .we seem forced to choose between three possibilities: either (1) we do after all know about the Trinity through a revelation in the form of propositions concerning the inner mysteries of the Godhead; or (2) there is an inherent threefoldness about every act of God's revelation, which requires us to think in trinitarian terms of the nature of God, even though we cannot speak of the different persons of the Trinity being responsible for specific facets of God's revelation; or (3) our Trinity of revelation is an arbitrary analysis of the activity of God, which though of value in Christian thought and devotion is not of essential significance.1 I think that this analytical approach is in important respects secondary to the genetic one. The first Christians spoke about God in the terms which we now try to analyze; surely the reasons why they used those terms are most relevant to a sound analysis. The main words whose usage needs to be fathomed are the Greek words prosöpon, hypostasis, ousia, andphysis.2 Prosöpon is the earliest of these terms to have attained an accepted conventional usage in early Christian speech about God, and therefore the chief determinant of the shape which the complex of terms was to take. -

Embracing Entrepreneurship

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses Perkins Thesis and Dissertations Spring 5-15-2021 Embracing Entrepreneurship Naomy Sengebwila [email protected] Naomy Nyendwa Sengebwila Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_ministry_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Folklore Commons, Food Security Commons, Food Studies Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Regional Economics Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social Justice Commons, Social Work Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Sengebwila, Naomy and Sengebwila, Naomy Nyendwa, "Embracing Entrepreneurship" (2021). Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses. 9. https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_ministry_etds/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Perkins Thesis and Dissertations at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Embracing Entrepreneurship How Christian Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship can Lead to Sustainable Communities in Zambia and Globally Approved by: Dr. Hal Recinos/Dr. Robert Hunt ___________________________________ Advisors Dr. Hugo Magallanes ___________________________________ -

Priscillian of Avila: Heretic Or Early Reformer? by Brian Wagner

Priscillian of Avila: Heretic or Early Reformer? by Brian Wagner Introduction The Lord Jesus Christ said, “For by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned” (Matthew 12:37).1 Though He was speaking of the last judgment, the principle of letting someone be judged, even in this life, by his own testimony is a sound one. The Bible also speaks of establishing one’s testimony in the mouth of two or three witnesses (1 Timothy 5:19), which is to be a safeguard against a false witness damaging someone’s reputation. History is a study of testimony. The primary source material written by an individual is often the best evidence by which to judge what that person believed and taught. Other contemporaries to that individual could also be used to evaluate whether he was presenting a consistent and coherent message at all times and whether his actions matched his words. As with all historical judgment of this kind, the testimony by friends or foes must be weighed with at least some suspicion of bias. Priscillian of Avila, from the fourth century, has been designated by most of history as a Christian heretic. This conclusion, made by many of his contemporary foes, led to his beheading by the civil authorities. After his death in A.D. 365, his writings were searched out for destruction, along with anyone promoting his teaching. Copies of some of his writings still survive. Very early ones, judged as possibly made within just a century of Priscillian’s martyrdom, were recovered at the University of Würzburg by Georg Schepss in 1885. -

Read the Essay on Mandatory Celibacy Here

What is the most underrated event of the past, and why is it so much more significant than people understand? When the Gregorian Reform was launched at the dawn of the second millennium, the papacy’s agenda was unequivocal. In an effort to centralise power and re-establish authority, a succession of popes both before and after Gregory VII (d. 1085), the reform’s namesake, introduced changes designed to free the Church from lay control. Secular rulers were stripped of their sacerdotal functions and clerics came to be the sole representatives of the Church, rather than the laity, as simony, investiture, and nicolaitism (i.e., clerical marriage) came under attack. The most far-reaching and long-lasting repercussions of these reforms, however, yet the most overlooked by historians, was the social upheaval caused by enforced clerical celibacy and its particularly devastating effect on women. The relentless onslaughts on clerical marriage instigated a social revolution that spanned the European continent, provoking riots for centuries, and, most perniciously, demonising half the world’s population as the reformers campaigned against women in order to make marriage less appealing. Misogyny has been woven so deeply into history that its nuanced causes and effects at any given time can be difficult to discern. But an analysis of the rhetoric used by reformers to vilify clerical wives and women in general can trace the revitalised hostility towards women beginning in the High Middle Ages to these reforms. For the first thousand years of Christianity, clerical marriage was common practice. Despite various church councils promulgating the ideal of celibacy, beginning with the Synod of Elvira in the fourth century which declared that all clerics were to “abstain from conjugal relations with their wives”1, deacons, priests, bishops, and even popes continued to marry and have children. -

A Vision for a Diocesan Family of Schools

A DIOCESAN FAMILY OF SCHOOLS A Vision for Catholic Schools in the Diocese of Leeds 1. Introduction 1.2 From the time of the restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy in 1850, the provision of, and support for, Catholic schools has been central to the life and mission of the Church in England and Wales. Ever since then, we have been required to work together as a Catholic community to rise to the political, economic and social challenges and opportunities which the Church’s mission in education has had to face. This mission has always taken place in a testing and changing context and our contemporary situation is no exception. 1.3 In the course of my visits to parishes over the past three years, I have met with the Chairs of Governors and Headteachers of the primary schools and academies located within those parishes to listen to their hopes and concerns. It has been a great encouragement to me to learn of the wonderful commitment and energy that exists in our diocesan schools. What has also emerged is a desire for greater clarity about the expectations on primary and secondary schools in relation to the development of the five multi-academy trusts within the diocese. 1.4 It is now just over six years since the Diocese of Leeds published its guidance for governors in October 2011, ‘Building the Future: Considering Multi-Academy Trusts’. This document presented a very clear description of ‘how’ schools could convert to academy status and proposed a framework of how five multi- academy trusts could be structured to offer parents a provision of Catholic education for 3-19 years. -

Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours This article is about the French saint. For the Caribbean minority faith. island, see Saint Martin. For other uses, see Saint Martin As the son of a veteran officer, Martin at fifteen was re- (disambiguation). quired to join a cavalry ala. Around 334, he was sta- tioned at Ambianensium civitas or Samarobriva in Gaul Martin of Tours (Latin: Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; (now Amiens, France).[2] It is likely that he joined the 316 – 8 November 397) was Bishop of Tours, whose Equites catafractarii Ambianenses, a heavy cavalry unit shrine in France became a famous stopping-point for listed in the Notitia Dignitatum. His unit was mostly cer- pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. emonial and did not face much combat.[3] Around his name much legendary material accrued, and he has become one of the most familiar and recognis- able Christian saints. As he was born in what is now Szombathely, Hungary, spent much of his childhood in Pavia, Italy, and lived most of his adult life in France, he is considered a spiritual bridge across Europe.[1] His life was recorded by a contemporary, the hagiographer Sulpicius Severus. Some of the ac- counts of his travels may have been interpolated into his vita to validate early sites of his cult. He is best known for the account of his using his military sword to cut his cloak in two, to give half to a beggar clad only in rags in the depth of winter. Conscripted as a soldier into the Roman army, he found the duty incompatible with the Christian faith he had adopted and became an early conscientious objector. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ALBERTO FERREIRO (October 2009) Address: Seattle Pacific University Department of History Seattle, WA 98119-1997 [email protected] (e-mail) 1-206-281-2939 (phone) 1-206-281-2771 (fax) Birthdate: 19 April, 1952, Mexico City, D.F. Education: Ph.D. 1986 University of California-Santa Barbara M. A. 1979 University of Texas-Arlington B. A. 1977 University of Texas-Arlington Languages: Fluent Spanish. Reading ability in Italian, French, Portuguese, German, Catalán, and Latin. Research Interests: Late Antique Gaul; Visigothic-Sueve Iberia; Medieval Monasticism; Christian Apocrypha; Cult of St. James; Priscillianism; and Early Christian-Medieval Heresy. Teaching Fields: Seattle Pacific University (Full Professor) At SPU since Autumn 1986 Fuller Theological Seminary , Seattle (Adjunct) 1991-1998 University of Sacramento, (Adjunct) 2006- University of Salamanca, (Visiting Professor/Lecturer) 2007- History of Christianity (Apostolic to Modern) Late Antiquity/Medieval History Medieval Monasticism - Spirituality Renaissance/Reformation Iberian Peninsula European Intellectual History 1 Publications: Books: Later Priscillianist Writings. Critical edition with historical commentary. Marco Conti and Alberto Ferreiro. Oxford University Press. (in preparation) The Visigoths in Gaul and Iberia (Update): A Supplemental Bibliography, 2007-2009. Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World. Alberto Ferreiro. E. J. Brill. (in preparation) 2008 The Visigoths in Gaul and Iberia (Update): A Supplemental Bibliography, 2004-2006. Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World, 35. Alberto Ferreiro. E. J. Brill, 2008. xxviii + 308 p. 2006 The Visigoths in Gaul and Iberia: (A Supplemental Bibliography, 1984- 2003). [Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World, 28]. Alberto Ferreiro. E. J. Brill: 2006. liv + 890 p. 2005 Simon Magus in Patristic, Medieval, and Early Modern Traditions.