FINAL History & Heritage Guide.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL ARCHIVES IRELAND Reference Code: 2005/7

TSCH/3: Central registry records Department of the Taoiseach NATIONAL ARCHIVES IRELAND Reference Code: 2005/7/600 Title: Correspondence between members of staff of the Office of the Minister for Justice and the Department of the Taoiseach, and WP Barbour of the Fermanagh Association of the Alliance Party, concerning border security between Counties Cavan and Donegal in the Republic of Ireland and County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland in the areas of Belcoo, Beleek, and Aghalane Bridge. Creation Date(s): 11 March, 1974, and 27 March, 1974 Level of description: Item Extent and medium: 3 pages Creator(s): Department of the Taoiseach Access Conditions: Open Copyright: National Archives, Ireland. May only be reproduced with the written permission of the Director of the National Archives. © National Archives, Ireland TSCH/3: Central registry records Department of the Taoiseach IFIG AN AIRE OLl AGUS CIRT (Office of the Minister for Justice) BAILE ATHA CLlATH 12MA \974 (Dubl in) /..1 t( M§rta, 1974. Runai Priob~ideach an Taoisigh. I am directed by the Minister for Justice to refer to the letter of 21st December to the Taoiseach from Mr . W. P. Barbour, Fermanagh Association of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland in which Mr . Barbour made certain suggestions about border security near Beleek, Belcoo and Aghalane Bridge. The Commissioner, Garda Siochana has indicated that a Garda unit with Army support is. nOvT operating permanently at Cloghore, near Beleek. The area is patrolled continuously and approaches to possible firing points on this side of the border are kept under observation by the patrols. With regard to Belcoo , the Commissioner states that there is a round- the- clock Garda check- point in Blacklion and that recently an Army unit has been supporting the Gardai there . -

200 Dpi) Lane 1:40000

580000 585000 590000 595000 600000 7°48'0"W 7°45'0"W 7°42'0"W 7°39'0"W 7°36'0"W 7°33'0"W 7°30'0"W 7°27'0"W 7°24'0"W GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR151 Product N.: 05ENNISKILLEN, v2, English Enniskillen - UNITED KINGDOM Flood - Pre-event situation Reference Map Strabane h h g g a ! u e o L N Omagh C 04 Dru reeby u ms Sc 0 r R lo 0 L r o e d o 0 a a 0 w i d Ro L (! n o e 0 0 u L gh r 0 0 o R u (! Er Kesh 3 3 g n B o d M h e la 0 0 e a a lv Belleek ck North 6 d 6 w o in NORTH B a Sea R a ATLANTIC Inner n te a Seas n r, o 03 OCEAN C 05 N Belfast " (! ^ 0 Enniskillen !Ballycassidy ' Ireland Irish Sea 4 Fermanagh 2 ° U 4 United L p F 5 o p Lisnaskea Coa i ! n E u e Kingdom Knockmanoul ! g r ! g r (! e n h 06 N e " r ^ p 0 ' o London 4 Ballinamallard 2 s L ° t A English Channel o 4 R France l u 5 l o e L g is a n d h R ea d o d Road Annalee, ad labby C Erne 10 n km e anno e Sh n m h d g a a ll o u R M !Tempo !Ballyreagh Cartographic Information op Drumscoll Full color ISO A1, medium resolution (200 dpi) Lane 1:40000 d a o 0 0.5 1 2 R tt km o T r u C l ly re d a Grid: WGS 1984 UTM zone 29N map coordinate system a g o h oad R R h R l o ag Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system e a re p C ± d a h C a o Legend C 0 M 0 0 on 0 0 R ea 0 5 oa oad 5 2 d po R 2 0 Tem ! 0 General Information Hydrology 6 6 Area of Interest Dam ad o Ro C oh r B o a Settlements River g h r ! i Populated Place m Stream a R r o a d a w Transportation d a N o o " 0 Lake B R ' 1 2 Primary Road ° 4 5 River Secondary Road N " 0 ' !Drumboy 1 2 ° 4 d 5 na Roa !Enniskillen Tras agh son R am R ig S ad o g Ro a d d a o R s d C ! o l o o R g C w o h h d o a t M o s a d l s R g o e o A l R e r b y e i v b s e e r l e e a o l v y i n i r E o Exposure within the AOI e S R h k R g e u o o Unit of measurement Total in AOI a L d d a D d o r oa Estimated population No. -

Newsletter 23-2 For

UK Belleek Collectors’ Group NNEEWWSSLL EETTTTEERR NNNNNNuuuuuummmmmmbbbbbbeeeeeerrrrrr 222222333333//////222222 SSSSSSeeeeeepppppptttttteeeeeemmmmmmbbbbbbeeeeeerrrrrr 222222000000000000222222 IIIttt hhhaaarrrdddllllyyy ssseeeeeemmmsss 333 mmmooo nnnttthhhsss aaagggooo ttthhhaaattt ttthhheee fffiiiirrrsssttt nnneeewww fffooorrrmmmaaattt nnneeewwwssslllleeetttttteeerrr wwwaaasss pppuuubbblllliiiissshhheeeddd ,,,, nnnooowww hhheeerrreee’’’’sss aaannnooottthhheeerrr.... AAA llllooottt hhhaaasss hhhaaappppppeeennneeeddd,,,, iiiinnnccclllluuudddiiiinnnggg ttthhheee bbbeeesssttt aaatttttteeennndddeeeddd AAAGGGMMM eeevvveeerrr,,,, aaa sssuuucccccceeessssssfffuuullll SSSiiiilllleeennnttt AAAuuuccctttiiiiooonnn,,,, aaa wwwooonnndddeeerrrfffuuullll dddaaayyy iiiinnn BBBooouuurrrnnneee EEEnnnddd wwwiiiittthhh JJJaaaccckkkiiiieee &&& JJJiiiimmm HHHooowwwdddeeennn,,,, aaannnddd ttthhheee eeexxxccciiii tttiiiinnnggg ––– ttthhhooouuuggghhh rrreeegggrrreeettttttaaabbblllleee ––– sssaaalllleee ooofff ttthhheee MMMiiiinnntttooonnn MMMuuussseeeuuummm pppiiiieeeccceee sss bbbyyy DDDooouuulllltttooonnn.... YYYooouuu cccaaannn rrreeeaaaddd aaabbbooouuuttt aaallllllll ttthhhiiiisss,,,, aaannnddd mmmuuuccchhh mmmooorrreee,,,, iiiinnn ttthhheee NNNeeewwwssslllleeetttttteeerrr.... I look forward to receiving articles for publication in your Newsletter, and please continue to send your personal news for publication to our Chairman, Jan Golaszewski. --- Gina Kelland UK Belleek Collectors’ Group Newsletter 23/2, September 2002 Contacts: Gina Kelland compiles the -

Lisnaskea (Updated May 2021)

Branch Closure Impact Assessment Closing branch: Lisnaskea 141 Main Street Lisnaskea BT92 0JE Closure date: 07/07/2021 The branch your account(s) will be administered from: Enniskillen Information correct as at: February 2021 1 What’s in this brochure The world of banking is changing and so are we Page 3 How we made the decision to close this branch What will this mean for our customers? Customers who need more support Access to Banking Standard (updated May 2021) Bank safely – Security information How to contact us Branch information Page 6 Lisnaskea branch facilities Lisnaskea customer profile (updated May 2021) How Lisnaskea customers are banking with us Page 7 Ways for customers to do their everyday banking Page 8 Other Bank of Ireland branches (updated May 2021) Bank of Ireland branches that will remain open Nearest Post Office Other local banks Nearest free-to-use cash machines Broadband available close to this branch Other ways for customers to do their everyday banking Definition of key terms Page 11 Customer and Stakeholder feedback Page 12 Communicating this change to customers Engaging with the local community What we have done to make the change easier 2 The world of banking is changing and so are we Bank of Ireland customers in Northern Ireland have been steadily moving to digital banking over the past 10 years. The pace of this change is increasing. Since 2017, for example, digital banking has increased by 50% while visits to our branches have sharply declined. Increasingly, our customers are using Post Office services with 52% of over-the-counter transactions now made in Post Office branches. -

Measuring What Matters

Measuring What Matters A pilot project carried out by Rural Community Network (NI) & Rose Regeneration Key Findings (See Page P10) 1. Every project analysed is delivering a positive social return. 2. Every project delivered several valuable and common outcomes. 3. Every project plans to use their SROI assessment as a way of demonstrating impact to current and potential new funders. 4. Projects value the importance of partnership working & collaboration to achieve results. 5. Measuring Social Value assists groups in better planning and delivery of projects. 6. Outcomes are as important as targets when planning project delivery. 7. Using this approach, is a user friendly, efficient way for small community/voluntary groups to evidence and measure their impact. 8. Funding bodies should encourage funded groups to adopt this model of measuring Social Value. 9. Groups that measure their impact get validation in the work that they carry out. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction & Background to the Project 3 2. Identifying the Projects & Methodology 6 3. Key Findings 10 4. Conclusion 13 Project Summaries 1. Cleenish Community Association 14 2. Lawrencetown, Lenaderg &Tullylish Community Association 20 3. Lislea Community Association 26 4. Mid Ulster Women’s Aid 32 5. Out and About 38 6. TIDAL 44 2 Introduction In Northern Ireland government departments, local councils and funders of the community / voluntary sector are increasingly asking community groups to demonstrate their effectiveness in terms of value for money that is being invested in them, as well as their real impact. For community groups, showing their value for money and social value is a positive thing. -

Visitor Map Attractions Activities Restaurants & Pubs Shopping Transport Fermanaghlakelands.Com Frances Morris Studio | Gallery Angela Kelly Jewellery

Experience Country Estate Living on a Private Island on Lough Erne. Northern Ireland’s Centrally located with Choice of Food & Only 4 Star Motel lots to see & do nearby Drink nearby Enjoy a stay at the beautifully restored 4* Courtyards,Cottages & Coach Houses. Award Winning Belle Isle Cookery School. Boating, Fishing, Mountain Biking & Bicycle Hire available. Choice of accommodation 4 Meeting & The Lodge At Lough Erne, variety of room types Event spaces our sister property Pet Friendly Accommodation & Free Wi-Fi. Book online www.motel.co.uk or contact our award winning reception T. 028 6632 6633 | E. [email protected] www.belle-isle.com | [email protected] | tel: 028 6638 7231 Tempo Road | Enniskillen | BT74 6HX | Co. Fermanagh NORTHERN IRELAND Monea Castle Visitor Map Attractions Activities Restaurants & Pubs Shopping Transport fermanaghlakelands.com Frances Morris Studio | Gallery Angela Kelly Jewellery l Original Landscapes Unique Irish Stone & Silver Jewellery l Limited Edition Prints Contemporary & Celtic Designs l Photographic Images One-off pieces a speciality 16 The Buttermarket Craft & Design Centre Market House, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, BT74 7DU 17 The Buttermarket Craft Centre, T: 028 66328741/ 0792 9337620 Enniskillen | Co. Fermanagh | BT74 7DU [email protected] T: 0044(0) 2866328645 | M: 0044(0) 7779787322 E: [email protected] www.francesmorris.com www.angelakellyjewellery.com Activities Bawnacre Centre Castle Street, Irvinestown 028 6862 1177 MAP1 E2 Blaney Caravan Park Belle Isle Estate & Belle Isle -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 29 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA2 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 193 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 195 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 199 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 204 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 219 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 222 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 222 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 244 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 253 Department -

Co. Fermanagh

Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology Queen’s University Belfast Data Structure Report No. 103 Excavations at Arney, Co. Fermanagh # Queen’s University Belfast Excavations at Arney, Co. Fermanagh (H 20725 37002) AE/14/01E Brian Sloan and Dermot Redmond Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Introduction 4 3. Account of the excavations 8 4. Account of the metal detecting survey 35 5. Conclusion 41 6. Recommendations for further work 42 7. Bibliography 43 8. Appendix 1: Context Register 45 9. Appendix 2: Harris Matrices 47 10. Appendix 3: Field Drawing Register 50 11. Appendix 4: Finds Register 51 12. Appendix 5: Photographic Register 53 Figures Figure # Detail Page Figure 1: General location map. 3 Figure 2: Google screen grab showing location of Arney. 3 Figure 3: 1st edition 6 inch OS map dated to 1835. 5 Figure 4: 3rd edition 6 inch OS map dated to c.1907. 6 Figure 5: Sites and Monuments details within 1 km of 7 the excavation area. Figure 6: Arney Schoolhouse on 3rd edition map 9 Figure 7: South-facing section of Trench One. 11 Figure 8: Post-excavation plan of Trench One 11 Figure 9: Schematic plan of features associated with the 16 Schoolhouse. Figure 10: Proposed development of Robert Lamb’s house 23 Figure 11: Plan of typical hearth-lobby house 24 Figure 12: Location of Trench Two on 3rd edition map 25 Figure 13: Post-excavation plan of Trench Two 31 (Robert Lambs house) Figure 14: Location of Trench Two on 3rd edition map 32 Figure 15: Post-excavation plan of Trench Three 34 Figure 16: Results of the metal detecting survey 38 Figure 17: Results of the metal detecting survey overlaid 39 On the 1st edition OS map Figure 18: Arney landscape showing the location of 40 the musket shot identified through metal detector survey Plates Plate # Detail Page Plate 1: View of probable demolition deposit (Context No. -

Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short Of

PRIMARY INSPECTION Brookeborough Primary School, Brookeborough, County Fermanagh Education and Training Inspectorate Controlled, co-educational Report of a Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short of Strike) in March 2017 Sustaining Improvement Inspection of Brookeborough Primary School, County Fermanagh (201-1894) Introduction In the last inspection held in September 2013, Brookeborough Primary School was evaluated overall as very good1. A sustaining improvement inspection (SII) was conducted on 8 March 2017. The purpose of the SII is to evaluate the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning. Four of the teaching unions which make up the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC) have declared industrial action primarily in relation to a pay dispute. This includes non-co-operation with the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI). Prior to the inspection, the school informed the ETI that all of the teachers including the principal would not be co-operating with the inspectors. The ETI has a statutory duty to monitor, inspect and report on the quality of education under Article 102 of the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) Order 1986. Therefore, the inspection proceeded and the following evaluations are based on the evidence as made available at the time of the inspection. Focus of the inspection Owing to the school’s participation in industrial action: • the inspection was unable to focus on evaluating the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning; and • lines of inquiry were not selected from the development plan priorities. -

1991 No. 317 ROAD TRAFFIC and VEHICLES

No. 317 Road Traffic and Vehicles 1435 1991 No. 317 ROAD TRAFFIC AND VEHICLES Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 4) Order (Northern Ireland) 1991 Made 22nd July 1991 Coming into operation 2nd September 1991 The Department of the Environment, in exercise of the powers conferred on it by Articles 2(2)(a) and 50(4) of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981 (b) and of every other power" enabling it in that behalf, orders and directs as follows: . Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 4) Order (Northern Ireland) 1991 and shall come into ·operation on 2nd September 1991. Speed restrictions on· certain roads 2. Each of the roads or lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 shall be a restricted road for the purposes of Article 50 of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981. 3. The length of road specified in Schedule 2 shall not be a restricted road for the purposes of said Article 50. Revocations 4. The provisions described in Schedule 3 are revoked. Sealed with the Official Seal of the Department of the Environment on 22nd July 1991. (L.s.) E. J. Galway Assistant Secretary (a) See definition of "Department" (b) S.l. 19811154 (N.l. 1) 1436 Road Traffic and Vehicles No. 317 SCHEDULE 1 Article 2 Restricted Roads 1. Barragh Gardens, Ballinamallard. 2. Castlemurry Drive, Ballimamallard. 3. Enniskillen Road, Route B46, Ballinamallard, from its junction with Coa Road, to a point approximately 57 metres south-west of its junction with Drummurry Gardens. 4. Femey View, Ballinamallard. -

A Revised List of the Executive Assets in County Fermanagh Is Provided and an Update Will Be Provided to the Assembly Library

Conor Murphy MLA Minister of Finance Clare House, 303 Airport Road West Belfast BT3 9ED Mr Seán Lynch MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Parliament Buildings Stormont AQW: 6772/16-21 Mr Seán Lynch MLA has asked: To ask the Minister of Finance for a list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh. ANSWER A revised list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh is provided and an update will be provided to the Assembly Library. Signed: Conor Murphy MLA Date: 3rd September 2020 AQW 6772/16-21 Revised response DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers -

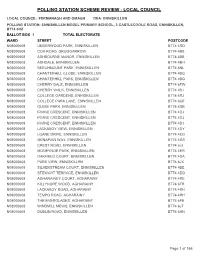

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: FERMANAGH AND OMAGH DEA: ENNISKILLEN POLLING STATION: ENNISKILLEN MODEL PRIMARY SCHOOL, 3 CASTLECOOLE ROAD, ENNISKILLEN, BT74 6HZ BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000608UNDERWOOD PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RD N08000608COA ROAD, DRUMGARROW BT74 4BS N08000608ASHBOURNE MANOR, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BB N08000608ASHDALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BH N08000608BEECHMOUNT PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6NL N08000608CHANTERHILL CLOSE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHANTERHILL PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHERRY DALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6FW N08000608CHERRY WALK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BJ N08000608COLLEGE GARDENS, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RJ N08000608COLLEGE PARK LANE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6GF N08000608GLEBE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DB N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608LACKABOY VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DY N08000608LOANE DRIVE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608MENAPIAN WAY, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4GS N08000608CREST ROAD, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JJ N08000608MONEYNOE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4ER N08000608OAKFIELD COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DA N08000608PARK VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JX N08000608SILVERSTREAM COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BE N08000608STEWART TERRACE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608AGHARAINEY COURT, AGHARAINY BT74 4RE N08000608KILLYNURE WOOD, AGHARAINY BT74 6FR N08000608LACKABOY ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608TEMPO ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608THE EVERGLADES, AGHARAINY BT74 6FE N08000608WINDMILL