Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Would You Understand What I Meant If I Said I Was Only Human?”

”Would you understand what I meant if I said I was only human?” The Image of the Vampire in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight and Charlaine Harris’s Dead Until Dark Jessica Dimming Fakulteten för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap English IV 15hp Supervisor Magnus Ullén Examiner Adrian Velicu HT 2012 Abstract In this essay I have decided to look at two very popular vampire novels today, Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris and Twilight by Stephenie Meyer. The focus of this essay is to look at the similarities and differences between these two novels and compare them to each other but also to the original legend of the vampire; this by using Dracula and other famous vampire stories to get an image of the vampire of pop-culture. I look at the features of the vampires, their abilities and different skills, and also sex and sexuality and how it is represented in these different stories. Even though the novels attract a wide audience they are written for a younger one and have a love story as its center. In this essay I give my opinion and view of the vampires and what I believe to be interesting with the morals and looks of the vampires as one of the different aspects. 2 Content Introduction 3 The Gothic novel 6 The legend of the vampire 7 Setting 10 Narrator 38 Features of the vampires in Twilight 43 Features of the vampires in Dead Until Dark 53 Vampires as sexual objects 67 Love and sexuality in Twilight 75 Love and sexuality in Dead Until Dark 86 Conclusion 95 Works cited 30 3 Introduction Dead Until Dark and Twilight by top selling authors Charlaine Harris and Stephenie Meyer are both novels written for young adults, somewhere between the ages of 14-24, with one major theme in common, vampires. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

Reorienting the Female Gothic: Curiosity and the Pursuit of Knowledge

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2020 REORIENTING THE FEMALE GOTHIC: CURIOSITY AND THE PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE Jenna Guitar University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Guitar, Jenna, "REORIENTING THE FEMALE GOTHIC: CURIOSITY AND THE PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE" (2020). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 1145. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/1145 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REORIENTING THE FEMALE GOTHIC: CURIOSITY AND THE PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE BY JENNA GUITAR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2020 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF JENNA GUITAR APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Jean Walton Christine Mok Justin Wyatt Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2020 ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the mode of the Female Gothic primarily by examining how texts utilize the role of curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge, paying close attention to how female characters employ these attributes. Existing criticism is vital to understanding the Female Gothic and in presenting the genealogy of feminist literary criticism, and yet I argue, this body of criticism often produces elements of essentialism. In an attempt to avoid and expose the biases that essentialism produces, I draw from Sara Ahmed’s theory of queer phenomenology to investigate the connections between the way that women pursue and circulate knowledge through education and reading and writing practices in the Female Gothic. -

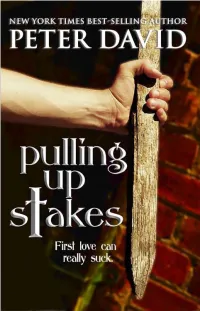

View Book Sample

Pulling Up Stakes A Tale of Relenting Horror PART ONE OF TWO Peter David CRAZY 8 PRESS Crazy Eight Press is an imprint of Second Age, Inc. Copyright © 2012 by Peter David Cover illustration by Glenn Hauman Design by Aaron Rosenberg All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Crazy 8 Press at the official Crazy 8 website: www.crazy8press.com First edition One My Dumb Ass Situation With My Mother ake up. It’s time to go out and kill something.” “W I moaned softly and pulled my blanket over my head. “Vincent!” said my mother, Dina Hammond, and this time she reached down and shook me so violently that I was sure my teeth were rattling. “Vince, for God’s sake! You haven’t got all night!” My head poked out from underneath the blanket like a turtle from its shell and I looked at her with bleary eyes. “I’m actually pretty sure that I do.” “Oh good. You’re alive.” My mother frowned in concern. “You’ve been sleeping through a lot of days lately.” “Well, I’ve been working nights.” “Let me check.” “Oh, Mom, for God’s sake—” “Let me. Check.” There was no waffling in Mom’s tone; noth- ing that indicated that there was going to be any wiggle room in the discussion or any possible negotiating of terms. You’d think I was fourteen instead of twenty-four. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Balticon 47 Program Participants

BALTICON 47 52 THE BSFAN Balticon 47 Program Participants JoAnn W. Abbott A. L. Davroe Heidi Hooper Danielle Ackley-McPhail Susan de Guardiola Starla Huchton Lisa Adler-Golden Donna Dearborn Kara Hurvitz D. H. Aire (Barry Nove) James K. Decker Michele Hymowitz Leigh Alexander Ming Diaz Eric Hymowitz Tristan Alexander Tim Dodge Christopher Impink Day Al-Mohamed Tom Doyle Noam Izenberg Scott H. Andrews Valerie Durham Mark Jeffrey Ami Angelwings James Durham Leslie Johnston Catherine A. Asaro Collin Earl Paula S. Jordan John Ashmead Gaia Eirich Jason Kalirai Lisa Ashton Chris Evans Amy L. Kaplan Thomas G. Atkinson Eric “Dr. Gandalf ” Fleischer Bruce Kaplan Jason Banks Halla Fleischer Debra Kaplan Brick Barrientos Judi Fleming William H. Kennedy Martin Berman-Gorvine Doc Frankenfield Kira Deja Biernesser D. Douglas Fratz James R. Knapp Steve Biernesser Nancy C. Frey Jonah Knight Joshua Bilmes Clint Gaige Beatrice Kondo Danny Birt Allison Gamblin Yoji Kondo (Eric Kotani) Roxanne Bland Charles E. Gannon Brian Koscienski Art Blumberg Lia Garrott A B Kovacs Sue Bowen Dr. Pamela L. Gay Laura E. Kovalcin Walter H. Boyes, Jr. Marty Gear Theodore Krulik William T. (Tom) Bridgman Veronica (V.) Giguere Alessandro La Porta Alessia Brio Phil Giunta Mur Lafferty J. Sherlock III Brown Alicia Goranson Jagi Lamplighter KT Bryski James L. Gossard Grig “Punkie” Larson Stephanie Burke Stephen Granade Marcus Lawrence Laura Burns Matthew Granoff Dina Leacock Mildred G. Cady Bob Greenberger R. Allen Leider Jack Campbell Irina Greenman Neal Levin Renee Chambliss Damien Walters Grintalis Emily Lewis Christine Chase Sonya “Patches” Gross Carey Lisse Robert R. Chase Gay Haldeman ScienceTim Livengood Bryan Chevalier Joe Haldeman Andy Love Ariel Cinii Elektra Hammond Steve Lubs Carl Cipra Eric V. -

• Mystery Sampler •

The King’s English Bookshop • Mystery Sampler • Cappuccino • Tales with froth, sass and plenty of action Janet Evanovich—Stephanie Plum Series Sue Grafton—Kinsey Milhone Series Lisa Lutz—Izzy Spellman Series Chris Ewan—Good Thief’s Guide Series Kate Atkinson Carl Hiaasen Espresso • These authors will keep you up at night Tana French Minette Walters Robert Goddard Susan Hill—Simon Serallier Series Ruth Rendell—Inspector Wexford Series Mo Hayer—Jack Caffrey Series Kathy Reich—Temperance Brennan Series Cara Black—Amie La Duc Series Laurie King—Mary Russell /Holmes Series Tea • Anything by Alexander McCall Smith Jacqueline Winspear–Maise Dobbs Series Agatha Christie–Hercule Poirot & Miss Marple Series Bourbon • Noir Ed McBain Walter Mosley Carroll O’connell Sarah Paretsky Fine Wines • Classic Mysteries Raymond Chandler Dashiel Hammet Dorothy L Sayers—Lord Peter Wimsey Georges Simenon—Maigret Wilkie Collins PD James—Adam Dalgleish Series Elizabeth George—Inspector Lindley Mysteries Vodka • Russian or Nordic Noir Steig Larsson—The Millenium Trillogy Henning Mankel—Wallender Tom Robb Smith Martin Cruz Smith Karen Fossum Rennie Airth Maj Sjowall And Per Wahloo Jo Nesbo Boris Akunin Camilla Läckberg Martini • Spy Stories To Leave You Shaken And Stirred Ian Fleming John le Carré Ted Bell Alex Berenson Stella Rimington Lee Child Noah Boyd Alan Furst Tom Clancy William Boyd Mike Lawson Alex Dryden Mead • Medieval Mysteries Ellis Peters–Cadfael C.J. Sansom Arianna Franklin Absinthe • Offbeat Christopher Fowler–Bryant And May Series Charlaine Harris -

Physical and Moral Survival in Stephen King's Universe

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-03-06 Monsters and Mayhem: Physical and Moral Survival in Stephen King's Universe Jaime L. Davis Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Davis, Jaime L., "Monsters and Mayhem: Physical and Moral Survival in Stephen King's Universe" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 2979. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2979 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Monsters and Mayhem: Physical and Moral Survival in Stephen King’s Universe Jaime L. Davis A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Carl Sederholm, Chair Kerry Soper Charlotte Stanford Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature Brigham Young University April 2012 Copyright © 2012 Jaime L. Davis All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Monsters and Mayhem: Physical and Moral Survival in Stephen King’s Universe Jaime L. Davis Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature, BYU Master of Arts The goal of my thesis is to analyze physical and moral survival in three novels from King’s oeuvre. Scholars have attributed survival in King’s universe to factors such as innocence, imaginative capacity, and career choice. Although their arguments are convincing, I believe that physical and moral survival ultimately depends on a character’s knowledge of the dark side of human nature and an understanding of moral agency. -

A PDF Copy of This Issue of Slayage Is Available Here

Slayage: Number Six Slayage 6 September 2002 [2.2] David Lavery and Rhonda V. Wilcox, Co-Editors Click on a contributor's name in order to learn more about him or her. A PDF copy of this issue (Acrobat Reader required) of Slayage is available here. A PDF copy of the entire volume can be accessed here. J. Gordon Melton (University of California, Santa Barbara), Images from the Hellmouth: Buffy the Vampire Slayer Comic Books 1998-2002 PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Reid B. Locklin (Boston University), Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the Domestic Church: Re-Visioning Family and the Common Good PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Frances Early (Mount St. Vincent University), Staking Her Claim: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Transgressive Woman Warrior PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) David Lavery (Middle Tennessee State University), "Emotional Resonance and Rocket Launchers": Joss Whedon's Commentaries on the Buffy the Vampire Slayer DVDs PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Recommended. Here and in each issue 1 3 of Slayage the editors will recommend 2 [1.2] 4 [1.4] [1.1] [1.3] writing on BtVS available on the Internet. 5 6 [2.2] 7 [2.3] 8 [2.4] [2.1] Robert Hanks, Deconstructing Buffy 11-12 9 10 [3.2] [3.3- [3.1] (from ) 4] Manuel de la Rosa, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the Girl Power Movement, and 13-14 Heroism 15 [4.3] [4.1- Archives Andy Sawyer, In a Small Town in 2] California . the Subtext is Becoming Text (from ) Anthony Cordesman, Biological Warfare and the "Buffy" Paradigm" Paula Graham, Buffy Wars: The Next file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/David%20Lavery/Lavery%20Documents/SOIJBS/Numbers/slayage6.htm (1 of 2)12/21/2004 4:23:36 AM Slayage, Number 6: Melton J. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper aligrunent can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Xnfonnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL; FEMALE AUTHORSHIP AND THE LITERARY VAMPIRE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor o f Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kathy S.