Rangelands Memo (August 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nth Past Memo June 2007.Pmd

PastoralPastoral MEMOMEMO © State of Western Australia, 2007. Northern Pastoral Region PO Box 19, Kununurra WA 6743 Phone: (08) 9166 4019 E-mail: [email protected] June 2007 ISSN 1033-5757 Vol. 28, No. 2 CONTENTS Where has the rain been falling? ........................................................................................................... 2 Welcome from the Editor ....................................................................................................................... 3 Kimberley and Pilbara ‘wet’ season round-up ........................................................................................ 4 Halls Creek Judas Donkey Program ...................................................................................................... 5 Alan Lawford to attend Australian Rural Leadership Program ................................................................. 6 Profitability and sustainability of Indigenous owned pastoral businesses ................................................ 6 Increase in Pastoral Water Grants ........................................................................................................11 Road trip ...............................................................................................................................................11 Horse movements ................................................................................................................................12 Bush Nurse ......................................................................................................................................... -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Conservation Significant Vertebrate Fauna Assessment

__________________________________________________________________________________ Mandora Cattle Company Pty Ltd Mandora Station Irrigated Fodder Production Project – Stage 1 Conservation significant vertebrate fauna assessment December 2017 Broome Bird Observatory BirdLife Australia Ltd PO Box 1313 Broome, WA, 6725 __________________________________________________________________________________ Mandora Station Irrigated Fodder Production Project – Stage 1 Conservation significant fauna assessment 0 __________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Project description .............................................................................................................................. 3 Study area ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 5 Adhering guidelines ............................................................................................................................ 5 Literature review and database searches ........................................................................................... 5 Conservation significant fauna .......................................................................................................... -

La Grange Agriculture Opportunities PLANNING the FUTURE for AGRICULTURE in the LA GRANGE REGION , WEST KIMBERLEY Issue 9 January/Feb 2015 from the Editor

La Grange Agriculture Opportunities PLANNING THE FUTURE FOR AGRICULTURE IN THE LA GRANGE REGION , WEST KIMBERLEY Issue 9 January/Feb 2015 From the Editor Inside this issue: From the editor 1 Project Seminar 2 Regional vision 3 January came and went before the chance to wish everyone Happy New Year so it’s Project Manager 4 update February well wishes from the team here in Broome. We hope 2015 is everything you hope for and that we get to work alongside you again this year. Guess the first rain 4 for the Wet winner I will be hitting the road in the next weeks as many return from a well earned break and I’m looking forward to catching up with the landholders of La Grange. The project end date of June 2016 is getting close and as we enter the last 17 months we look forward to finalizing the resource assessment and other investigations and support tools, and showcasing these at the 2015 regional workshop. The DAFWA project team presented a seminar update at the end of last year to Department and Industry people in Perth and the packed room indicated a keenness to hear what the project has been doing and where we are heading from here. facebook.com/dafwalagrange Finalising the regional vision for future agriculture development in La Grange is a high priority for this last year. A vision statement will be developed that the project and landholders can use to clearly outline what the residents of La Grange want. If you haven’t had a chance to have your say as a landholder, make sure you contact me. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Asian Renewable Energy Hub: Marine State Waters Environmental Impact Assessment

Asian Renewable Energy Hub: Marine State Waters Environmental Impact Assessment 1250_01_001/1 Rev 0 September 2018 P:\IntercontinentalEnergy\1250_01SubseaCableApp&Studies\001_OriginalScope\Reports\MarineImpactAssessment\HVDCCable_Sta teMarineEIA_Rev0_20180927.docm Asian Renewable Energy Hub: Marine State Waters Environmental Impact Assessment Prepared for NW Interconnected Power Pty Ltd Prepared by BMT Western Australia Pty Ltd September 2018 Report No. 1250_01_001/1 Rev 0 Client: NW Interconnected Power Pty Ltd Document history Distribution No. copies Revision Author Recipients Organisation Date & format NW Interconnected A Bevilaqua A Tancock A Power 1 x doc 20/10/17 R De Roach G Humphries Biota NW Interconnected R De Roach A Tancock B Power 1 x pdf 10/11/17 A Bevilaqua G Humphries Biota NW Interconnected A Tancock C A Bevilaqua Power 1 x pdf 11/09/18 G Humphries Biota NW Interconnected A Tancock 0 A Bevilaqua Power 1 x pdf 27/09/18 G Humphries Biota Review Revision Reviewer Intent Date A Tancock A First Draft, no review G Humphries No review, awaiting updates to be made A Tancock B in reference to the Environmental G Humphries Scoping Document C A Tancock Client review 11/09/18 Status This report is 'Draft' until approved for final release, as indicated below by inclusion of signatures from: (i) the author and (ii) a Director of BMT Western Australia Pty Ltd (BMT) or their authorised delegate. A Draft report may be issued for review with intent to generate a 'Final' version, but must not be used for any other purpose. Approved for final release: Author Director (or delegate) Date: 27/09/18 Date: 27/09/18 Disclaimer This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of NW Interconnected Power Pty Ltd, and is subject to and issued in accordance with the agreed terms and scope between NW Interconnected Power Pty Ltd and BMT Western Australia Pty Ltd (BMT). -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community. -

Native Title Information Handbook : Western Australia / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Native Title Information Handbook Western Australia 2016 © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies AIATSIS acknowledges the funding support of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Native Title Research Unit (NTRU) acknowledges the generous contributions of peer reviewers and welcomes suggestions and comments about the content of the Native Title Information Handbook (the Handbook). The Handbook seeks to collate publicly available information about native title and related matters. The Handbook is intended as an introductory guide only and is not intended to be, nor should it be, relied upon as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If you are aware that this publication contains any errors or omissions please contact us. Views expressed in the Handbook are not necessarily those of AIATSIS. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 02 6261 4223 Fax 02 6249 7714 Email [email protected] Web www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Native title information handbook : Western Australia / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN: 9781922102577 (ebook) Subjects: Native title (Australia)--Western Australia--Handbooks, manuals, etc. Aboriginal Australians--Land tenure--Western Australia. Land use--Law and legislation--Western Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Western Australia. Other Creators/Contributors: -

Eighty-Mile Beach, Western Australia

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). This Ramsar Information Sheet has been converted to meet the 2009 – 2012 format, but the RIS content has not been updated in this conversion. The new format seeks some additional information which could not yet be included. This information will be added when future updates of this Ramsar Information Sheet are completed. Until then, notes on any changes in the ecological character of the Ramsar site may be obtained from the Ecological Character Description (if completed) and other relevant sources. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Compiled by the Department of Conservation and Land DD MM YY Management (DCLM). All inquiries should be directed to: Jim Lane Designation date Site Reference Number DCLM 14 Queen Street Busselton WA 6280 Australia Tel: +61-8-9752-1677 Fax: +61-8-9752-1432 email: [email protected]. 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: November 2003 3. Country: Australia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: The precise name of the designated site in one of the three official languages (English, French or Spanish) of the Convention. Alternative names, including in local language(s), should be given in parentheses after the precise name. Eighty-mile Beach, Western Australia 5. Designation of new Ramsar site or update of existing site: Eighty-mile Beach, Western Australia was designated on 7 June 1990. -

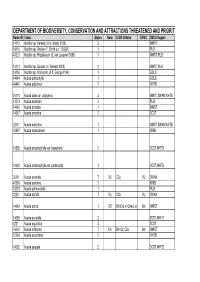

Threatened and Priority Flora List 5 December 2018.Xlsx

DEPARTMENT OF BIODIVERSITY, CONSERVATION AND ATTRACTIONS THREATENED AND PRIORITY Name ID Taxon Status Rank IUCN Criteria EPBC DBCA Region 14112 Abutilon sp. Hamelin (A.M. Ashby 2196) 2 MWST 14110 Abutilon sp. Onslow (F. Smith s.n. 10/9/61) 1 PILB 43021 Abutilon sp. Pritzelianum (S. van Leeuwen 5095) 1 MWST,PILB 14114 Abutilon sp. Quobba (H. Demarz 3858) 2 MWST,PILB 14155 Abutilon sp. Warburton (A.S. George 8164) 1 GOLD 14044 Acacia adinophylla 1 GOLD 44442 Acacia adjutrices 3 WHTB 16110 Acacia alata var. platyptera 4 MWST,SWAN,WHTB 13074 Acacia alexandri 3 PILB 14046 Acacia ampliata 1 MWST 14047 Acacia amyctica 2 SCST 3210 Acacia anarthros 3 MWST,SWAN,WHTB 43557 Acacia anastomosa 1 KIMB 14585 Acacia ancistrophylla var. lissophylla 2 SCST,WHTB 14048 Acacia ancistrophylla var. perarcuata 3 SCST,WHTB 3219 Acacia anomala TVUC2a VU SWAN 43580 Acacia anserina 2 KIMB 13073 Acacia aphanoclada 1 PILB 3220 Acacia aphylla TVUC2a VU SWAN 14049 Acacia aprica TCRB1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v) EN MWST 14050 Acacia arcuatilis 2 SCST,WHTB 3221 Acacia argutifolia 4 SCST 14051 Acacia aristulata TENB1+2c; C2a EN MWST 12248 Acacia ascendens 2 WHTB 14052 Acacia asepala 2 SCST,WHTB 14725 Acacia ataxiphylla subsp. ataxiphylla 3 SCST,WHTB B1ab(iii,iv,v)+2ab(iii 14687 Acacia ataxiphylla subsp. magna TEN,iv,v); C2a(i); D EN WHTB 19507 Acacia atopa 3 MWST 14053 Acacia auratiflora TVUC2a(i) EN WHTB 3230 Acacia auricoma 3 GOLD 14054 Acacia auripila 2 PILB 12249 Acacia awestoniana TCRC2a(ii) VU SCST 31784 Acacia barrettiorum 2 KIMB 41461 Acacia bartlei 3 SCST 3237 Acacia benthamii 2 SWAN 44472 Acacia besleyi 1 SCST 14611 Acacia bifaria 3 SCST 3243 Acacia botrydion 4 WHTB 13509 Acacia brachyphylla var. -

RCM008 Saunders Spring Condition Report

Resource Condition Report for a Significant Western Australian Wetland Saunders Spring 2009 Figure 1 – Vegetation atop the peat deposit at Saunders Spring. This report was prepared by: Glen Daniel, Environmental Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre 6983 Stephen Kern, Botanist, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre 6983 Adrian Pinder, Senior Research Scientist, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Anna Nowicki, Technical Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Invertebrate sorting and identification was undertaken by: Nadine Guthrie, Research Scientist, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Ross Gordon, Technical Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Prepared for: Inland Aquatic Integrity Resource Condition Monitoring Project, Strategic Reserve Fund, Department of Environment and Conservation Version 3 (August 2009) Suggested Citation: DEC (2009) Resource Condition Report for a Significant Western Australian Wetland: Saunders Spring. Prepared for Inland Aquatic Integrity Resource Condition Monitoring (IAI RCM) Project. Department of Environment and Conservation. Perth, Australia. Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................1 1.1. Site Code ...............................................................................................................1 -

International Airport Codes

Airport Code Airport Name City Code City Name Country Code Country Name AAA Anaa AAA Anaa PF French Polynesia AAB Arrabury QL AAB Arrabury QL AU Australia AAC El Arish AAC El Arish EG Egypt AAE Rabah Bitat AAE Annaba DZ Algeria AAG Arapoti PR AAG Arapoti PR BR Brazil AAH Merzbrueck AAH Aachen DE Germany AAI Arraias TO AAI Arraias TO BR Brazil AAJ Cayana Airstrip AAJ Awaradam SR Suriname AAK Aranuka AAK Aranuka KI Kiribati AAL Aalborg AAL Aalborg DK Denmark AAM Mala Mala AAM Mala Mala ZA South Africa AAN Al Ain AAN Al Ain AE United Arab Emirates AAO Anaco AAO Anaco VE Venezuela AAQ Vityazevo AAQ Anapa RU Russia AAR Aarhus AAR Aarhus DK Denmark AAS Apalapsili AAS Apalapsili ID Indonesia AAT Altay AAT Altay CN China AAU Asau AAU Asau WS Samoa AAV Allah Valley AAV Surallah PH Philippines AAX Araxa MG AAX Araxa MG BR Brazil AAY Al Ghaydah AAY Al Ghaydah YE Yemen AAZ Quetzaltenango AAZ Quetzaltenango GT Guatemala ABA Abakan ABA Abakan RU Russia ABB Asaba ABB Asaba NG Nigeria ABC Albacete ABC Albacete ES Spain ABD Abadan ABD Abadan IR Iran ABF Abaiang ABF Abaiang KI Kiribati ABG Abingdon Downs QL ABG Abingdon Downs QL AU Australia ABH Alpha QL ABH Alpha QL AU Australia ABJ Felix Houphouet-Boigny ABJ Abidjan CI Ivory Coast ABK Kebri Dehar ABK Kebri Dehar ET Ethiopia ABM Northern Peninsula ABM Bamaga QL AU Australia ABN Albina ABN Albina SR Suriname ABO Aboisso ABO Aboisso CI Ivory Coast ABP Atkamba ABP Atkamba PG Papua New Guinea ABS Abu Simbel ABS Abu Simbel EG Egypt ABT Al-Aqiq ABT Al Baha SA Saudi Arabia ABU Haliwen ABU Atambua ID Indonesia ABV Nnamdi Azikiwe Intl ABV Abuja NG Nigeria ABW Abau ABW Abau PG Papua New Guinea ABX Albury NS ABX Albury NS AU Australia ABZ Dyce ABZ Aberdeen GB United Kingdom ACA Juan N.