Rubber Vulcanization (Edited from Wikipedia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for Christine Parente

9/25/2020 Bibliography for Christine Parente Bibliography Sorted by Author / Title. Adeyemi, Tomi. Children of blood and bone. New York : Henry Holt and Co., 2018. Seventeen-year-old Zélie, her older brother Tzain, and rogue princess Amari fight to restore magic to the land and activate a new generation of magi, but they are ruthlessly pursued by the crown prince, who believes the return of magic will mean the end of the monarchy. [Fic] Ahmed, Samira (Fiction writer). Love, hate & other filters. New York, NY : Soho Teen, [2018]. Maya Aziz, seventeen, is caught between her India-born parents world of college and marrying a suitable Muslim boy and her dream world of film school and dating her classmate, Phil, when a terrorist attack changes her life forever. Alexander, Kwame. The crossover. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2014]. Fourteen-year-old twin basketball stars Josh and Jordan wrestle with highs and lows on and off the court as their father ignores his declining health. Alexander, Michelle. The new Jim Crow : mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. 10th anniversary ed. New York : The New Press, 2020. Argues that mass incarceration of African- and Latino Americans in the United States is a form of social control, and contends the civil rights community needs to become more active in protecting the rights of criminals. EBOOK 937 ALL Allan, Tony, 1946-. Exploring the life, myth, and art of ancient Rome. New York : Rosen Pub., 2012. An illustrated exploration of the mythology, art, religion, civilization, and customs of ancient Rome. EBOOK 948 ALL Allan, Tony, 1946-. -

Yale Law School 2019–2020

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Yale Law School 2019–2020 Yale Law School Yale 2019–2020 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 115 Number 11 August 10, 2019 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 115 Number 11 August 10, 2019 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse Avenue, New Haven CT 06510. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. backgrounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, against any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 disability, status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 4th Floor, 203.432.0849. -

The Rubber Industry in New Jersey

CHAPTER 4 suggested citation: Medrano-Bigas, Pau. The Forgotten Years of Bibendum. Michelin’s American Period in Milltown: Design, Illustration and Advertising by Pioneer Tire Companies (1900-1930). Doctoral dissertation. University of Barcelona, 2015 [English translation, 2018]. THE RUBBER INDUSTRY IN NEW JERSEY The implantation and development of the pioneering rubber industry in the United States is clearly marked by three stages, in each of which a specific geographical area is the protagonist. The first indus- trial applications took place in Boston and adjacent towns, particularly for its well-established footwear industry, between 1825 and 1840. In a second phase, approximately between 1850 and 1890, the hege- mony of the sector moved to the state of New Jersey with epicenters located in Trenton and New Brunswick. In this phase, an extensive array of new industrial rubber-derived products was produced, which included solid tires for bicycles and wagons. Towards the end of the century, with the emergence of motor vehicles, a third stage materialized, in which the tire industry and other components of auto- mobile mechanics (belts, gaskets, brake pads, etc.) were developed. During the first three decades of 1900, the city of Akron and surrounding areas in the state of Ohio were the clear leaders in this new industrial adventure. 1. From the Amazon jungle to Boston The milky liquid or latex obtained from bleeding the trunks of Hevea brasilensis—a tree typical of Ama- zonian forests in Brazil—and converted by coagulation into solid rubber, was not sent from this South American country to foreign markets in this form, but rather as locally manufactured products such as bottles or footwear. -

Famous People Charles Goodyear

Famous People Charles Goodyear Pre-Reading Warm Up Questions ☀ Charles Goodyear 1. Have you ever heard the term “vulcanization of rubber”? Can you guess what it means? Charles Goodyear was an American who invented the vulcanization 2. Have you heard of the international company called of rubber. Vulcanization is a process that uses chemicals and heat to Goodyear Tires? change and strengthen rubber so that it can be used to make products such as tires and inflatable life rafts. 3. Have you ever invented anything? If so, describe your invention. Goodyear was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on December 29, 4. Do you think most inventors become rich from their 1800. He had little schooling. As a young man, he worked with his inventions? father in their hardware store in Philadelphia. When their business failed, Goodyear was sent to debtors’ prison because he could not 5. What can inventors do to prevent other people from pay his debts. stealing their ideas? While he was in prison, he began to think of ways to make rubber usable. When he got out of prison, he made some rubber outer shoes, but the rubber melted when it got warm and the shoes were ruined. His experiments with rubber produced a strong smell in the family’s house. When the neighbors complained, Goodyear, his wife, and their children moved to New York City. Goodyear had to sell all of his family’s possessions to continue with his experiments. His family was soon very poor, and Goodyear spent more time in debtors’ prison. Goodyear did not give up though. -

The University of Akron Fact Book, 2003. INSTITUTION Akron Univ., OH

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 478 816 HE 036 047 AUTHOR Gaylord, Thomas; Maffei, Diane; Rogers, Greg; Sponseller, Eric TITLE The University of Akron Fact Book, 2003. INSTITUTION Akron Univ., OH. PUB DATE 2003-04-00 NOTE 339p.; Produced by the Institutional Planning, Analysis, Reporting and Data Administration. For the 2002 Fact Book, see ED 469 644. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www3.uakron.edu/iplan/factbook2003/ factbook2003_complete.pdf. PUB TYPE Books (010) Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) -- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; *College Faculty; *Enrollment; Higher Education; *Institutional Characteristics; Professional Education; Program Descriptions ; *Student Characteristics IDENTIFIERS *University of Akron OH ABSTRACT This fact book provides comprehensive information about the University of Akron, Ohio. It is intended to be a reference for answering frequently asked questions about the institution. With an enrollment of more than 24,300, the University of Akron is among the 75 largest public universities in the United States. Approximately 800 full-time faculty members teach undergraduates and graduates from 42 states and 84 foreign countries. Information is provided in these categories: (1) "Historical and General Information"; (2) "Academic & Program Information"; (3) "Student Information";(4) "Faculty & Staff Information"; (5) "Budget & Financial Information";(6) "Research & Information Services"; and (7) "Facilities Information." A glossary and list of abbreviations -

Rachel Hayes Rubber Rampage

1 Rachel Hayes Rubber Rampage: The Era that Produced Vulcanized Rubber November 21, 2013 Fall 2013 Kansas State University History of the United States to 1877 HIST 251 Dr. Morgan Morgan Abstract: Rubber, a waterproof gum, was demanded by many in the early 1830’s. While useful as a waterproof, elastic fabric in its flexible state which is at room temperature, the rubber froze in the winter and turned sticky in the summer. During this era, many knew that whoever discovered the stable state would gain an abundant fortune. This is what Charles Goodyear achieved in 1839 by adding sulfur to the natural rubber; this process is now known as vulcanization. This scientific breakthrough revolutionized the automobile industry. Society had been using the iron wheel since 1000 BC which was an extremely rickety trail ride. The newly stabilized rubber absorbed the shock from the imperfections in the road in the form of a tire; thus, creating a more stable ride. This heighted the urge for the public to create gas powered vehicles. Everything about the discovery of rubber and vulcanization drove the automobile industry into the astounding business that it currently is. Key Words: Rubber, Vulcanization, Charles Goodyear, Tires, Automobiles 2 Vulcanized rubber heightened the urge to create human powered and gasoline powered vehicles. The rubber tires absorb the shock from imperfections in the road; wooden wheels cannot do this, which, in turn, creates more momentum for the vehicle with rubber tires because miniscule flaws do not slow it down. As a mechanical engineering major, I am interested in the vulcanization process which led to the use of rubber tires instead of wooden wheels. -

BUSINESS EXPECTATIONS and PLANT EXPANSION with Special Reference to the Rubber Industry DISSERTATION

BUSINESS EXPECTATIONS AND PLANT EXPANSION With Special Reference to the Rubber Industry DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Dootor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University o ' t & r b Clarence R. Jung, Jr. The Ohio State University 1953 Approved by: leading up to Hicks' contribution follows* Critical opinion usually credits John Maurice Clark with being the first modern economist to recognize and label the economic conditions of the accelerator# as is pointed out above* His work was not very rigorous mathematically and he made relatively few statistical tests of his models* His work did not refer, for example, to some important problems of cycle theory: What are the initiating factors in the oscillations and what are the conditions tinder which the oscillations are likely to be explosive, damped, or constant? Ragnar Frisch offered an explanation of the initiating factors in the oscillations and some conclusions on how these factors seem likely to be sufficient for maintaining the oscillations*9 Initiating factors he said are "exogenous" to the economic system under consideration (for example war, famine, flood, technological change) and come upon it at erratic intervals* These shocks may be likened to successive blows struck at a pendulum swinging against some friction* The blows keep the pendulum swinging at varying amplitudes and speeds* Erratic shocks instigate oscillations, irregular in B T. N. Carver, Aftalion, and Bickerdike clearly formulated such a principle prior to Clark's article in 1919* See Fisher, loc* cit., pp ltfli-7* 9 Frisch, Ragnar, "Propagation Problems and Impulse Problems in Dynamic Economics," Economic Essays in Honour of Gustav Cassel, London: Geo Allen and Unwin, Ltd.T"l933. -

Naming the Goodyear Blimp: Corporate Iconography<Sup>1</Sup>

Naming the Goodyear Blimp: Corporate Iconographyl Christine De Vinne Ursuline College Attentive to names as corporate markers, the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Akron, Ohio, in 2006 offered consumers an unprecedented opportunity to name its newest airship. The company's "Name the Blimp" contest, which ran in two month-long segments, elicited over 21 ,000 entries, including the winning "Spirit of Innovation." In the context of Goodyear history, I analyze the contest' design and results, especially its strategies for maximizing both corporate and consumer satisfaction, as a demonstration of the power of names to market image and promote customer loyalty. In 2006, the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Akron, Ohio, sponsored a national contest to name its latest airship. From 21,300 entries, the corporation selected ten finalists, which it then submitted to public vote on its website, nametheblimp.com. The winner, announced in May 2006 to media fanfare, declared the new blimp the Spirit of Innovation. The ship was hailed in a christening ceremony attended by 1,500 people on 21 June, its official name emblazoned on the flank of its car. Goodyear, which maintains its fleet solely for marketing purposes, recognizes in this first-of-a-kind contest a resounding consumer relations success, a strong return on its publicity investment, and a conviction that the winning entry aptly conveys the firm's capacity for product leader- ship. The contest is equally apt as illustration of the significance of names in a corporate context. Goodyear's historical attention to names and naming rituals, the popular response to its "Name the Blimp" invitation, and the oversight that guaranteed a winner consonant with corporate expectations point beyond the specifics of the contest to the theoretical underpinnings of name-based advertising. -

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Brooklyn College 2015 Music: Its Language, History, and Culture Douglas Cohen CUNY Brooklyn College Brooklyn College Library and Academic IT How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bc_oers/4 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC: ITS LANGUAGE, HISTORY, AND CULTURE A Reader for Music 1300 RAY ALLEN DOUGLAS COHEN NANCY HAGER JEFFREY TAYLOR Copyright © 2006, 2007, 2008, 2014 by the Conservatory of Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. Original text by Ray Allen, Douglas Cohen, Nancy Hager, and Jeffrey Taylor with contributions by Marc Thorman. ISBN: 978-0-9913887-0-7 Music: Its Language, History and Culture by the Conservatory of Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en_US. Based on a work at http://www.music1300.info/reader. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.music1300.info/reader. Cover art and design by Lisa Panazzolo Photos by John Ricasoli CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Elements of Sound and Music 3 Elements of Sound: Frequency, Amplitude, Wave Form, Duration 3 Elements -

GOODYEAR V. DAY. [2 Wall

YesWeScan: The FEDERAL CASES Case No. 5,569. GOODYEAR V. DAY. [2 Wall. Jr. 283; Merw. Pat Inv. 655.]1 Circuit Court, D. New Jersey. Sept. 28, 1852. PATENTS—PERPETUAL INJUNCTION—SENDING CASE TO JURY—WHO ENTITLED TO PATENT—REDUCING SPECULATION TO PRACTICE. 1. Where a court of equity, having heard a case on full proofs, is well satisfied of the originality of an invention, the regularity of a patent, and of the fact of infringement, it will not send the case to a jury to have its verdict prior to granting a perpetual injunction. It will grant it at once, especially if the questions in the case, though questions of fact, are of that kind that a court can decide them on the testimony of men of science, as well as, or better than a jury; and where a jury trial would be long, costly or troublesome. [Cited in Buchanan v. Howland, Case No. 2,074; Roberts v. Reed Torpedo Co., Id. 11,910; McMillin v. Barclay, Id. 8902; Wise v. Grand Ave. Ry. Co., 33 Fed. 278.] 1 GOODYEAR v. DAY. 2. It is not necessary for the protection of a, patent, that the patentee should be the first person, who conceived the practicability or existence of the thing patented, but who, though making important experiments, was unable to bring them to any successful or valuable result. He who reduces speculation to practice, whose experiments result in discovery, and who then afterwards first puts the public into practical and useful possession of the compound, art, machine or product, is enti- tled to the patent right. -

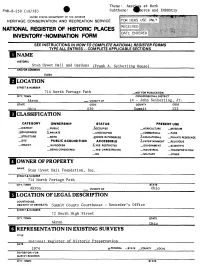

Name Location Classifi Cation Owner of Property

Theme: Amer^a at Work FHR-8-250 (10/78) Subtheme: (^pnerce and INDUStry UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ::W::*:*:*x*:«*:w^^ HERITAGE CONSERVATION AND RECREATION SERVICE FOR HCRS USE ONLY :;:::;: i;RECEIVEL) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY-NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens (Frank A. Seiberling House! AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 714 North Portage Path _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Akron __ VICINITY OF 14 - John Seiberling, Jr. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 039 Summit 153 CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC —^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JCBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —^WORK IN PROGRESS ^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^.ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Stan Hywet Hall Foundation, Inc. STREET & NUMBER 714 North Portage Path CITY. TOWN STATE Akron VICINITY OF Ohio LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Summit County Courthouse - Recorder's Office STREET & NUMBER 72 South High Street CITY. TOWN STATE Akron Ohio REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Keenster of Historic Preservation DATE 1974 9^-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT ..DETERIORATED ^UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE______ —FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Summary Stan Hywet Hall, the Frank A. Seiberling House, is a Tudor-Stuart Rivival style mansion. -

The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company

The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company Topic Guide for Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) Introduction In 1898, Frank Seiberling of Akron, Ohio, established the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. He named it after Charles Goodyear, inventor of vulcanized rubber, and developed its trademark, the Wingfoot, based on a newel post on the staircase in his home. The company produced tires for bicycles and carriages, horseshoe pads and poker chips, and later expanded to the automobile and aircraft industries. Goodyear continued to grow nationally and internationally and was the largest tire manufacturer in the world by 1916 when it adopted the slogan: “More people ride on Goodyear tires than any other kind.” During World War I, Goodyear provided airships and observation balloons for the U.S. Army Air Service and built its first blimp in 1917. It was the world’s largest rubber company in 1926 and remains a multi-billion dollar company today. Important Dates . 1898: Frank Seiberling of Akron, Ohio, establishes the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. The business is incorporated in August and production begins in November with 13 employees. 1899: Goodyear began to produce tires for “horseless carriages” or automobiles. 1901: Goodyear provides Henry Ford with racing tires. The Wingfoot trademark is used in an advertisement for the first time in Philadelphia’s Saturday Evening Post. 1903: Paul W. Litchfield patents the first tubeless automobile tire. 1907: Henry Ford purchase 1,200 sets of tires for his Model T automobile. 1909: Goodyear manufactures its first aircraft tire. 1911: Goodyear begins experimenting with airship design. 1912: Goodyear establishes one of the first industrial hospitals in the United States.