Green Genes—Comparative Genomics of the Green Branch of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RED ALGAE · RHODOPHYTA Rhodophyta Are Cosmopolitan, Found from the Artic to the Tropics

RED ALGAE · RHODOPHYTA Rhodophyta are cosmopolitan, found from the artic to the tropics. Although they grow in both marine and fresh water, 98% of the 6,500 species of red algae are marine. Most of these species occur in the tropics and sub-tropics, though the greatest number of species is temperate. Along the California coast, the species of red algae far outnumber the species of green and brown algae. In temperate regions such as California, red algae are common in the intertidal zone. In the tropics, however, they are mostly subtidal, growing as epiphytes on seagrasses, within the crevices of rock and coral reefs, or occasionally on dead coral or sand. In some tropical waters, red algae can be found as deep as 200 meters. Because of their unique accessory pigments (phycobiliproteins), the red algae are able to harvest the blue light that reaches deeper waters. Red algae are important economically in many parts of the world. For example, in Japan, the cultivation of Pyropia is a multibillion-dollar industry, used for nori and other algal products. Rhodophyta also provide valuable “gums” or colloidal agents for industrial and food applications. Two extremely important phycocolloids are agar (and the derivative agarose) and carrageenan. The Rhodophyta are the only algae which have “pit plugs” between cells in multicellular thalli. Though their true function is debated, pit plugs are thought to provide stability to the thallus. Also, the red algae are unique in that they have no flagellated stages, which enhance reproduction in other algae. Instead, red algae has a complex life cycle, with three distinct stages. -

Red Algae (Bangia Atropurpurea) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Red Algae (Bangia atropurpurea) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2014 Revised, March 2016, September 2017, October 2017 Web Version, 6/25/2018 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From NOAA and USGS (2016): “Bangia atropurpurea has a widespread amphi-Atlantic range, which includes the Atlantic coast of North America […]” Status in the United States From Mills et al. (1991): “This filamentous red alga native to the Atlantic Coast was observed in Lake Erie in 1964 (Lin and Blum 1977). After this sighting, records for Lake Ontario (Damann 1979), Lake Michigan (Weik 1977), Lake Simcoe (Jackson 1985) and Lake Huron (Sheath 1987) were reported. It has become a major species of the littoral flora of these lakes, generally occupying the littoral zone with Cladophora and Ulothrix (Blum 1982). Earliest records of this algae in the basin, however, go back to the 1940s when Smith and Moyle (1944) found the alga in Lake Superior tributaries. Matthews (1932) found the alga in Quaker Run in the Allegheny drainage basin. Smith and 1 Moyle’s records must have not resulted in spreading populations since the alga was not known in Lake Superior as of 1987. Kishler and Taft (1970) were the most recent workers to refer to the records of Smith and Moyle (1944) and Matthews (1932).” From NOAA and USGS (2016): “Established where recorded except in Lake Superior. The distribution in Lake Simcoe is limited (Jackson 1985).” From Kipp et al. (2017): “Bangia atropurpurea was first recorded from Lake Erie in 1964. During the 1960s–1980s, it was recorded from Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, Lake Ontario, and Lake Simcoe (part of the Lake Ontario drainage). -

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

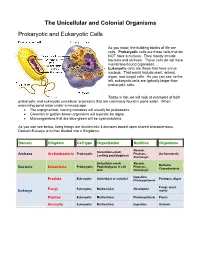

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct. -

Mitochondrial Genomes of the Early Land Plant Lineage

Dong et al. BMC Genomics (2019) 20:953 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-6365-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Mitochondrial genomes of the early land plant lineage liverworts (Marchantiophyta): conserved genome structure, and ongoing low frequency recombination Shanshan Dong1,2, Chaoxian Zhao1,3, Shouzhou Zhang1, Li Zhang1, Hong Wu2, Huan Liu4, Ruiliang Zhu3, Yu Jia5, Bernard Goffinet6 and Yang Liu1,4* Abstract Background: In contrast to the highly labile mitochondrial (mt) genomes of vascular plants, the architecture and composition of mt genomes within the main lineages of bryophytes appear stable and invariant. The available mt genomes of 18 liverwort accessions representing nine genera and five orders are syntenous except for Gymnomitrion concinnatum whose genome is characterized by two rearrangements. Here, we expanded the number of assembled liverwort mt genomes to 47, broadening the sampling to 31 genera and 10 orders spanning much of the phylogenetic breadth of liverworts to further test whether the evolution of the liverwort mitogenome is overall static. Results: Liverwort mt genomes range in size from 147 Kb in Jungermanniales (clade B) to 185 Kb in Marchantiopsida, mainly due to the size variation of intergenic spacers and number of introns. All newly assembled liverwort mt genomes hold a conserved set of genes, but vary considerably in their intron content. The loss of introns in liverwort mt genomes might be explained by localized retroprocessing events. Liverwort mt genomes are strictly syntenous in genome structure with no structural variant detected in our newly assembled mt genomes. However, by screening the paired-end reads, we do find rare cases of recombination, which means multiple concurrent genome structures may exist in the vegetative tissues of liverworts. -

Ecophysiology of Four Co-Occurring Lycophyte Species: an Investigation of Functional Convergence

Research Article Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence Jacqlynn Zier, Bryce Belanger, Genevieve Trahan and James E. Watkins* Department of Biology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, USA Received: 22 June 2015; Accepted: 7 November 2015; Published: 24 November 2015 Associate Editor: Tim J. Brodribb Citation: Zier J, Belanger B, Trahan G, Watkins JE. 2015. Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence. AoB PLANTS 7: plv137; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv137 Abstract. Lycophytes are the most early divergent extant lineage of vascular land plants. The group has a broad global distribution ranging from tundra to tropical forests and can make up an important component of temperate northeast US forests. We know very little about the in situ ecophysiology of this group and apparently no study has eval- uated if lycophytes conform to functional patterns expected by the leaf economics spectrum hypothesis. To determine factors influencing photosynthetic capacity (Amax), we analysed several physiological traits related to photosynthesis to include stomatal, nutrient, vascular traits, and patterns of biomass distribution in four coexisting temperate lycophyte species: Lycopodium clavatum, Spinulum annotinum, Diphasiastrum digitatum and Dendrolycopodium dendroi- deum. We found no difference in maximum photosynthetic rates across species, yet wide variation in other traits. We also found that Amax was not related to leaf nitrogen concentration and is more tied to stomatal conductance, suggestive of a fundamentally different sets of constraints on photosynthesis in these lycophyte taxa compared with ferns and seed plants. These findings complement the hydropassive model of stomatal control in lycophytes and may reflect canaliza- tion of function in this group. -

Functional Gene Losses Occur with Minimal Size Reduction in the Plastid Genome of the Parasitic Liverwort Aneura Mirabilis

Functional Gene Losses Occur with Minimal Size Reduction in the Plastid Genome of the Parasitic Liverwort Aneura mirabilis Norman J. Wickett,* Yan Zhang, S. Kellon Hansen,à Jessie M. Roper,à Jennifer V. Kuehl,§ Sheila A. Plock, Paul G. Wolf,k Claude W. dePamphilis, Jeffrey L. Boore,§ and Bernard Goffinetà *Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut; Department of Biology, Penn State University; àGenome Project Solutions, Hercules, California; §Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute and University of California Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Walnut Creek, California; and kDepartment of Biology, Utah State University Aneura mirabilis is a parasitic liverwort that exploits an existing mycorrhizal association between a basidiomycete and a host tree. This unusual liverwort is the only known parasitic seedless land plant with a completely nonphotosynthetic life history. The complete plastid genome of A. mirabilis was sequenced to examine the effect of its nonphotosynthetic life history on plastid genome content. Using a partial genomic fosmid library approach, the genome was sequenced and shown to be 108,007 bp with a structure typical of green plant plastids. Comparisons were made with the plastid genome of Marchantia polymorpha, the only other liverwort plastid sequence available. All ndh genes are either absent or pseudogenes. Five of 15 psb genes are pseudogenes, as are 2 of 6 psa genes and 2 of 6 pet genes. Pseudogenes of cysA, cysT, ccsA, and ycf3 were also detected. The remaining complement of genes present in M. polymorpha is present in the plastid of A. mirabilis with intact open reading frames. All pseudogenes and gene losses co-occur with losses detected in the plastid of the parasitic angiosperm Epifagus virginiana, though the latter has functional gene losses not found in A. -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista. -

Brown Algae and 4) the Oomycetes (Water Molds)

Protista Classification Excavata The kingdom Protista (in the five kingdom system) contains mostly unicellular eukaryotes. This taxonomic grouping is polyphyletic and based only Alveolates on cellular structure and life styles not on any molecular evidence. Using molecular biology and detailed comparison of cell structure, scientists are now beginning to see evolutionary SAR Stramenopila history in the protists. The ongoing changes in the protest phylogeny are rapidly changing with each new piece of evidence. The following classification suggests 4 “supergroups” within the Rhizaria original Protista kingdom and the taxonomy is still being worked out. This lab is looking at one current hypothesis shown on the right. Some of the organisms are grouped together because Archaeplastida of very strong support and others are controversial. It is important to focus on the characteristics of each clade which explains why they are grouped together. This lab will only look at the groups that Amoebozoans were once included in the Protista kingdom and the other groups (higher plants, fungi, and animals) will be Unikonta examined in future labs. Opisthokonts Protista Classification Excavata Starting with the four “Supergroups”, we will divide the rest into different levels called clades. A Clade is defined as a group of Alveolates biological taxa (as species) that includes all descendants of one common ancestor. Too simplify this process, we have included a cladogram we will be using throughout the SAR Stramenopila course. We will divide or expand parts of the cladogram to emphasize evolutionary relationships. For the protists, we will divide Rhizaria the supergroups into smaller clades assigning them artificial numbers (clade1, clade2, clade3) to establish a grouping at a specific level.