Chapter 1: the Two Congresses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

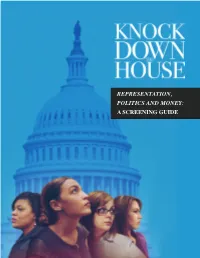

REPRESENTATION, POLITICS and MONEY: a SCREENING GUIDE “I’M Running Because of Cori Bush

REPRESENTATION, POLITICS AND MONEY: A SCREENING GUIDE “I’m running because of Cori Bush. I’m running because of Paula Jean Swearengin. I’m running because everyday Americans deserve to be represented by everyday Americans.” - Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 About the Film 5 Letter from Director, Rachel Lears 6 Using the Guide Tips for Leading Conversations Pre-Screening Discussion Questions 9 Post-Screening Background and Context Who Knocked in 2018? Representation: Who is in Congress and Why it Matters How Money Works in Elections The Politics of Elections 25 Get Involved Share the Film Spark Conversations Across Party Lines Vote and Get Out the Vote Support a Candidate Run for Office 33 Resources for Further Learning 3 ABOUT THE FILM Knock Down the House is the story of four working-class women who embraced the challenge of running for Congressional office in the 2018 midterm elections. They are four of the record numbers who organized grassroots campaigns, rejected corporate PAC money and challenged the notion that everyday people can run successful campaigns against sitting incumbents. Collectively these candidates herald a cultural and political shift to transform the process of running and electing our representatives. Such changes do not occur in a vacuum, nor are they about a singular issue. Rather they about changing the attitudes, behaviors, terms, and outcomes of existing and entrenched norms and building towards a more inclusive and representative government. 4 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR, RACHEL LEARS I’ve been making films about politics since the days of Occupy Wall Street. After having a baby in 2016, I thought I might take a break from political filmmaking—but the day after the election, I knew I had no choice. -

'Our Revolution' Meets the Jacksonians (And the Midterms)

Chapter 16 ‘Our Revolution’ Meets the Jacksonians (And the Midterms) Whole-Book PDF available free At RippedApart.Org For the best reading experience on an Apple tablet, read with the iBooks app: Here`s how: • Click the download link. • Tap share, , then • Tap: Copy to Books. For Android phones, tablets and reading PDFs in Kindles or Kindle Apps, and for the free (no email required) whole-book PDF, visit: RippedApart.Org. For a paperback or Kindle version, or to “Look Inside” (at the whole book), visit Amazon.com. Contents of Ripped Apart Part 1. What Polarizes Us? 1. The Perils of Polarization 2. Clear and Present Danger 3. How Polarization Develops 4. How to Depolarize a Cyclops 5. Three Political Traps 6. The Crime Bill Myth 7. The Purity Trap Part 2. Charisma Traps 8. Smart People Get Sucked In 9. Good People Get Sucked In 10. Jonestown: Evil Charisma 11. Alex Jones: More Evil Charisma 12. The Charismatic Progressive 13. Trump: Charismatic Sociopath Part 3. Populism Traps 14. What is Populism; Why Should We Care? 15. Trump: A Fake Jacksonian Populist 16. ‘Our Revolution’ Meets the Jacksonians 17. Economics vs. the Culture War 18. Sanders’ Populist Strategy 19. Good Populism: The Kingfish 20. Utopian Populism 21. Don’t Be the Enemy They Need Part 4. Mythology Traps 22. Socialism, Liberalism and All That 23. Sanders’ Socialism Myths 24. The Myth of the Utopian Savior 25. The Establishment Myth 26. The Myth of the Bully Pulpit 27. The Myth of the Overton Window Part 5. Identity Politics 28. When the Klan Went Low, SNCC Went High 29. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

One Hundred Third Congress January 3, 1993 to January 3, 1995

ONE HUNDRED THIRD CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1993 TO JANUARY 3, 1995 FIRST SESSION—January 5, 1993, 1 to November 26, 1993 SECOND SESSION—January 25, 1994, 2 to December 1, 1994 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—J. DANFORTH QUAYLE, 3 of Indiana; ALBERT A. GORE, JR., 4 of Tennessee PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ROBERT C. BYRD, of West Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—WALTER J. STEWART, 5 of Washington, D.C.; MARTHA S. POPE, 6 of Connecticut SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MARTHA S. POPE, 7 of Connecticut; ROBERT L. BENOIT, 6 of Maine SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—THOMAS S. FOLEY, 8 of Washington CLERK OF THE HOUSE—DONNALD K. ANDERSON, 8 of California SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—WERNER W. BRANDT, 8 of New York DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JAMES T. MALLOY, 8 of New York DIRECTOR OF NON-LEGISLATIVE AND FINANCIAL SERVICES—LEONARD P. WISHART III, 9 of New Jersey ALABAMA Ed Pastor, Phoenix Lynn Woolsey, Petaluma SENATORS Bob Stump, Tolleson George Miller, Martinez Nancy Pelosi, San Francisco Howell T. Heflin, Tuscumbia Jon Kyl, Phoenix Ronald V. Dellums, Oakland Richard C. Shelby, Tuscaloosa Jim Kolbe, Tucson Karen English, Flagstaff Bill Baker, Walnut Creek REPRESENTATIVES Richard W. Pombo, Tracy Sonny Callahan, Mobile ARKANSAS Tom Lantos, San Mateo Terry Everett, Enterprise SENATORS Fortney Pete Stark, Hayward Glen Browder, Jacksonville Anna G. Eshoo, Atherton Tom Bevill, Jasper Dale Bumpers, Charleston Norman Y. Mineta, San Jose Bud Cramer, Huntsville David H. Pryor, Little Rock Don Edwards, San Jose Spencer Bachus, Birmingham REPRESENTATIVES Leon E. Panetta, 12 Carmel Valley Earl F. -

Food Safety Issues

FOOD SAFETY ISSUES HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENT OPERATIONS, RESEARCH, AND FOREIGN AGRICULTURE OF THE COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 19, 1992 MINOR-USE PESTICIDES, INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT, AND BIOLOGICAL PESTICIDES FEBRUARY 26, 1992 RISK ASSESSMENT FOR ESTABLISHING PESTICIDE RESIDUE TOLERANCE MARCH 4, 1992 PREEMPTION OF LOCAL AUTHORITY UNDER THE FEDERAL INSECTICIDE, FUNGICIDE, AND RODENTICIDE ACT MARCH 11, 1992 USDA PESTICIDE PROGRAMS Serial No. 102-58 Printed for the use of the Committee on Agriculture U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57-806 WASHINGTON : 1992 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0-16-039128-8 COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE E (KIKA) DE LA GARZA, Texas, Chairman WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina, TOM COLEMAN, Missouri, Vice Chairman Ranking Minority Member GEORGE E. BROWN, JR., California RON MARLENEE, Montana CHARLIE ROSE, North Carolina LARRY J. HOPKINS, Kentucky GLENN ENGLISH, Oklahoma PAT ROBERTS, Kansas LEON E. PANETTA, California BILL EMERSON, Missouri JERRY HUCKABY, Louisiana SID MORRISON, Washingto:, DAN GLICKMAN, Kansas STEVE GUNDERSON, Wisconsin CHARLES W. STENHOLM, Texas TOM LEWIS, Florida HAROLD L. VOLKMER, Missouri ROBERT F. (BOB) SMITH, Oregon CHARLES HATCHER, Georgia LARRY COMBEST, Texas ROBIN TALLON, South Carolina WALLY HERGER, California HARLEY 0. STAGGERS, JR., West Virginia JAMES T. WALSH, New York JIM OLIN, Virginia DAVE CAMP, Michigan TIMOTHY J. PENNY, Minnesota WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado RICHARD H. STALLINGS, Idaho BILL BARRETT, Nebraska DAVID R. NAGLE, Iowa JIM NUSSLE, Iowa JIM JONTZ, Indiana JOHN A. BOEHNER, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota THOMAS W. -

Extensions of Remarks

17098 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 31, 1989 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CAPTIVE NATIONS WEEK new hope that the people of Cambodia, Well, I have just returned-hopeful, and Laos, and Vietnam will regain some day encouraged-from visits to Poland and Hun their long-denied political and religious free gary, two nations on the threshold of histor HON. ROBERT K. DORNAN dom. Such hope has also returned for many ic change. And I can say to you: The old OF CALIFORNIA of our neighbors to the south. In Nicaragua ideas are blowing away. Freedom is in the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES and other Latin American nations, popular air. Monday, July 31, 1989 resistance to attempts at repression by local For forty years, Poland and Hungary en dictators-as well as resistance to political dured what's been called the dilemma of the Mr. DORNAN of California. Mr. Speaker, and military interference from Cuba and single alternative: one political party, one would like to call your attention to the Presi the Soviet Union-has proved to be formida definition of national interest, one social dent's proclamation regarding the captive na ble. and economic model. In short, one future tions of the world and also the eloquent In Eastern Europe, even as we see rays of prescribed by an alien ideology. light in some countries, we must recognize speech President Bush made last week in the But, in fact, that future meant no future. that brutal repression continues in other For it denied to individuals, choice; to soci White House Rose Garden to commemorate parts of the region, including the persecu eties, pluralism; and to nations, self-determi Captive Nations Week, 1989. -

Safety Last the POLITICS of E. GOLI and OTHER FOOD-BORNE KILLERS

Safety Last THE POLITICS OF E. GOLI AND OTHER FOOD-BORNE KILLERS THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY About the Center for Public Integrity THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY, founded in 1989 by a group of concerned Americans, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, tax-exempt educational organization created so that important national issues can be investigated and analyzed over a period of months without the normal time or space limitations. Since its inception, the Center has investigated and disseminated a remarkably wide array of information in nearly thirty published Center Reports. The Center's books and studies are resources for journalists, academics, and the general public, with databases, backup files or government documents, and other information available as well. This report and the views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of individual members of the Center for Public Integrity's Board of Directors or Advisory Board. THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY 1634 I Street, N.W. Suite 902 Washington, B.C. 20006 Telephone: (202) 783-3900 Facsimile: (202) 783-3906 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.publicintegrity.org Copyright ©1998 The Center for Public Integrity All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, with- out permission in writing from The Center for Public Integrity. ISBN: 1882583-09-4 Printed in the United States of America Contents Summary 1 1 Introduction 5 2 The Captive Congress 9 3 The Microbial Menace 23 4 Farms and Factories 31 5 Fewer and Bigger 45 6 R&R: Recall and Recovery 51 7 "Have a Cup of Coffee and Pray" 57 8 Conclusion 71 List of Tables 75 Notes 93 THE INVESTIGATIVE TEAM Executive Director Charles Lewis Director of Investigative Projects Bill Hogan Senior Editor William O'Sullivan Chief of Research Bill Allison Senior Researchers David Engel Adrianne Hari John Kruger Eric Wilson Writers Paul Cuadros Patrick J. -

Biden-Like House Candidates Beat Those to Their Left

MEMO Published March 25, 2021 • 7 minute read Biden-Like House Candidates Beat Those to Their Left David de la Fuente Senior Political Analyst @dpdelafuente Regardless of how you look at it, President Joe Biden did better than House Democratic candidates in the 2020 elections. Yet while House Democrats across the board underperformed the top of the ticket, and challengers did worse than incumbents, the data is clear that moderate non-incumbent House Democratic candidates fared much better than their leftwing counterparts—by a signicant margin. In fact, leftwing nominees lost more than double the amount of support than moderate Democrats on average compared to Biden, due to some combination of ticket-splitting and under-voting. Let’s look at the national picture of House Democrats general underperformance. Biden defeated Trump 51.3% to 46.9% (4.5 points with rounding), while House Democrats defeated House Republicans 50.8% to 47.7% (3.1 points). That means House Democrats underperformed Biden by a margin of 1.4 points across the country. 1 You can also compare how many Congressional districts Biden won compared to how many House Democrats won. By that measure, House Democrats only underperformed Biden by two districts: Biden won 224 and House Democrats won 222. Of course, there were some split-ticket districts, but not many, with nine choosing Biden and a House Republican and seven choosing Trump and a House Democrat. Generally speaking, House Democratic incumbents did better compared to Biden than non- incumbent candidates. All seven Democrats who won Trump districts were incumbents who had been able to build their own brand. -

Our Revolution” Meets the Jacksonians (And the Midterms)

Chapter 16 ‘Our Revolution” Meets the Jacksonians (And the Midterms) Whole-Book PDF available free At RippedApart.Org For the best reading experience on an iPhone, read with the iBooks app: Here`s how: • Click the download link. • Tap share, , then • Tap: Copy to Books. “Copy to Books” is inside a 3-dot “More” menu at the far right of the row of Apps. For Android phones, tablets and reading PDFs in Kindles or Kindle Apps, and for the free (no email required) whole-book PDF, visit: RippedApart.Org. For a paperback or Kindle version, or to “Look Inside” (at the whole book), visit Amazon.com. Contents of Ripped Apart Part 1. What Polarizes Us? 1. The Perils of Polarization 2. Clear and Present Danger 3. How Polarization Develops 4. How to Depolarize a Cyclops 5. Three Political Traps 6. The Crime Bill Myth 7. The Purity Trap Part 2. Charisma Traps 8. Smart People Get Sucked In 9. Good People Get Sucked In 10. Jonestown: Evil Charisma 11. Alex Jones: More Evil Charisma 12. The Charismatic Progressive 13. Trump: Charismatic Sociopath Part 3. Populism Traps 14. What is Populism; Why Should We Care? 15. Trump: A Fake Jacksonian Populist 16. ‘Our Revolution’ Meets the Jacksonians 17. Economics vs. the Culture War 18. Sanders’ Populist Strategy 19. Good Populism: The Kingfish 20. Utopian Populism 21. Don’t Be the Enemy They Need Part 4. Mythology Traps 22. Socialism, Liberalism and All That 23. Sanders’ Socialism Myths 24. The Myth of the Utopian Savior 25. The Establishment Myth 26. The Myth of the Bully Pulpit 27. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, February 22, 1990 the House Met at 11 A.M

2290 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE February 22, 1990 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, February 22, 1990 The House met at 11 a.m. and was I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the and friend, .Mr. Tony Pope, president called to order by the Speaker pro United States of America, and to the Repub of Catawba Transportation in Clare tempore [Mr. GEPHARDT]. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for mont, NC. all. We had the opportunity to trade DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO ideas and discuss many issues under TEMPORE consideration by the Congress. One CONGRESSMAN ANNUNZIO WEL issue of mutual concern is legislation The SPEAKER pro tempore laid COMES FATHER ANTHONY MI being considered by the House Com before the House the following com CIUNAS mittee on Energy and Commerce, the munication from the Speaker: (Mr. ANNUNZIO asked and was Used Oil Recycling Act of 1989. The WASHINGTON, DC, given permission to address the House bill encourages proper handling and February 22, 1990. for 1 minute and to revise and extend recycling of used oil and prohibits the I hereby designate the Honorable RICHARD A. GEPHARDT to act as Speaker pro tempore his remarks.> Administrator of the Environmental today. Mr. ANNUNZIO. Mr. Speaker, it is a Protection Agency [EPA] from listing THOMAS S. FOLEY, genuine pleasure for me to welcome to used oil as a hazardous waste. Speaker of the House of Representatives. our Nation's Capitol Father Anthony Like Mr. Pope of Claremont, many Miciunas, pastor of St. Peter Church of my constituents back in North in Kenosha, WI, who offered the PRAYER Carolina are interested in a safe, clean, opening prayer. -

Amarillo Gathering California Gathering Fishing Tournament

1 CAL FARLEY'S Boys Ranch Alumni Association Newsletter 2007 SPRING EDITION http://calfarleysboysranchalumni.org Amarillo Gathering Big Texan Steak Ranch - May 19, 2007 RSVP Les Saker 806/672-2292 California Gathering Camarillo, CA June 23-24, 2007 Cal Farley's Boys Ranch Alumni Association P.O. Box 9435 Fishing Tournament Amarillo, Texas 79105 September 1, 2007 Newsletter Comments or Submissions Visit the website for up-to-date news and some awesome pictures of 806-322-2645 past various events. Also, please notice that there is a new mailing 800-687-3722 x2645 address for the Alumni Association. This new address should help in Alumni Aftercare streamlining the mail process. Kim Reeves 806-322-2531 800-687-3722 x2531 **IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT** Table of Contents Cal Farley’s and the Alumni Association are updating our alumni mailing list and we need your help. Since Cal Farley’s Contact Information 1 and the Alumni Association are separate entities, we require 2007 Gatherings 1 your permission for both entities to have access to your per- Website 1 sonal information. Cal Farley’s requires your information to as- Mission 1 sure you keep receiving the newsletter. Farley Quote 1 Condolences 2 Please send an email giving permission to share your informa- Alumni News 2 tion or fill out the enclosed coupon and return to us in order to Congratulations! 2 help us in this endeavor. Scholarships 2 Where Are You? 2 Cheree Gilliam Forum Online 3 600 W. 11th Avenue Committees 3 Amarillo, TX 79101 Board of Directors 3 [email protected] Prayer Requests 3 fax: 806/372-6638 attn: Cheree President’s Corner 3 Upcoming Events 4 Donation Form 4 Visit our website at: Committee Report 5 Address Coupon 5 http://calfarleysboysranchalumni.org Our Mission The mission of the Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch Alumni Association is to provide a professional network of former ranchers who seek to carry on the spirit of family through fellowship, association and support. -

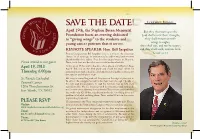

Save the Date!

SAVE THE DATE! April 19th, the Stephen Breen Memorial But they that wait upon the Foundation hosts an evening dedicated Lord shall renew their strength; to “giving wings” to the students and they shall mount up with young cancer patients that it serves. wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Hon. Bill Sarpalius and they shall walk, and not faint. Former Congressman Bill Sarpalius story is a story of the American Isaiah 40:31 Dream. At an early age, he overcame polio and his two brothers were abandoned by their father. They lived in vacant houses in Houston, Please attend as our guest. Texas, with their mother who was suicidal and an alcoholic. April 19, 2018 At the age of 13, he and his brothers where placed at Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch. Bill was in the fifth grade and could not read. When he Thursday, 6:00pm graduated from high school he only had a hundred dollars in his pocket one suitcase and no place to go. St. Patrick Cathedral His story is compelling and will keep you on the edge of your seat as he tells of the struggles he and his brothers went through. He tells of Pastoral Center the love and determination he and his brothers had to help their 1206 Throckmorton St. suicidal mother. His life shows us with determination and hard work Fort Worth, TX 76102 we can over come adversity. He ran for the Texas Senate and started his race with only $25.00 but was determined to do something about the problem of alcohol and drug abuse.