2011 Institutes for Texas Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Induction Banquet Congratulations to My Fellow Pan American Broncs and the Class of 2014

2014 Induction Banquet Congratulations to my fellow Pan American Broncs and the Class of 2014 Rick Villarreal Insurance Agency 2116 W. University Dr. • Edinburg, Tx 78539 (956)383-7001 (office) • (956)383-7009 (fax) http://www.farmersagent.com/rvillarreal1 2 x Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame President’s Message Welcome to the 27th Annul Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame Induction Banquet. 2014 marks the 29th annuiversary of the organization and the third year in a row that we have held our induction banquet here in the City of Pharr. The Board of Directors are happy to be here this evening and are happy everyone could join us tonight for this year’s event. The Sports Hall of Fame is a non-profit organization dedicated to bringing recognition to our local talent—those who have represented the Rio Grande Valley throughout Texas and the Nation. Tonight will be a memorable night for the inductees and their families. We all look forward to hearing their stories of the past and of their most memorable moments during their sports career. I would like to congratulate this year’s 2014 Class of seven inductees. A diverse group consisting of one woman – Nancy Clark (Harlingen), who participated in Division I tennis at The University of Texas at Austin and went on to win many championships in open tournaments across the state of Texas and nation over the next 31 years. The six men start with Jesse Gomez (Raymondville), who grew up as a local all around athlete and later played for Texas Southmost College, eventually moving on to play semi-pro baseball in the U.S. -

Recorded Texas Historic Landmark Marker Without Post

Texas Historical Commission staff (AD), 12/14/2009 18" x 28" Recorded Texas Historic Landmark Marker without post for attachment to masonry Hidalgo County (Job #09HG08) Subject EB (Atlas) UTM: 14 577059E 2899459N Location: McAllen, 1009 North 10th St. LAMAR JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL THE McALLEN SCHOOL BOARD AUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION OF LAMAR HIGH SCHOOL IN 1938, THROUGH A BOND ELECTION AND FUNDING FROM THE PUBLIC WORKS ADMINISTRATION. ARCHITECT MARION LEE WALLER’S ORIGINAL DESIGN INCLUDED AN L-SHAPED FLOOR PLAN ONLY ONE ROOM DEEP, WITH EAST- AND SOUTH- FACING CLASSROOMS OPENING ONTO BREEZEWAYS FOR MAXIMUM CIRCULATION IN THE DAYS BEFORE AIR CONDITIONING. THE SCHOOL OPERATED AS A HIGH SCHOOL FOR ONLY FIVE YEARS, UNTIL DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW SITE; THIS CAMPUS HAS CONTINUED AS A JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL WITH SEVERAL ADDITIONS. THE SPANISH COLONIAL REVIVAL STYLE TWO-STORY REINFORCED CONCRETE AND WOOD FRAMED BUILDING FEATURES A BUFF BRICK EXTERIOR, CLAY TILE ROOF AND CAST STONE DETAILING. RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK – 2009 MARKER IS PROPERTY OF THE STATE OF TEXAS RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK MARKERS: 2009 Official Texas Historical Marker Sponsorship Application Form Valid October 15, 2008 to January 15, 2009 only This form constitutes a public request for the Texas Historical Commission (THC) to consider approval of an Official Texas Historical Marker for the topic noted in this application. The THC will review the request and make its determination based on rules and procedures of the program. Filing of the application for sponsorship is for the purpose of providing basic information to be used in the evaluation process. The final determination of eligibility and therefore approval for a state marker will be made by the THC. -

Hot Topic Presents the 2011 Take Action Tour

For Immediate Release February 14, 2011 Hot Topic presents the 2011 Take Action Tour Celebrating Its 10th Anniversary of Raising Funds and Awareness for Non-Profit Organizations Line-up Announced: Co-Headliners Silverstein and Bayside With Polar Bear Club, The Swellers and Texas in July Proceeds of Tour to Benefit Sex, Etc. for Teen Sexuality Education Pre-sale tickets go on sale today at: http://tixx1.artistarena.com/takeactiontour February 14, 2011 – Celebrating its tenth anniversary of raising funds and awareness to assorted non-profit organizations, Sub City (Hopeless Records‟ non-profit organization which has raised more than two million dollars for charity), is pleased to announce the 2011 edition of Take Action Tour. This year‟s much-lauded beneficiary is SEX, ETC., the Teen-to-Teen Sexuality Education Project of Answer, a national organization dedicated to providing and promoting comprehensive sexuality education to young people and the adults who teach them. “Sex is a hot topic amongst Take Action bands and fans but rarely communicated in a honest and accurate way,” says Louis Posen, Hopeless Records president. “Either don't do it or do it right!" Presented by Hot Topic, the tour will feature celebrated indie rock headliners SILVERSTEIN and BAYSIDE, along with POLAR BEAR CLUB, THE SWELLERS and TEXAS IN JULY. Kicking off at Boston‟s Paradise Rock Club on April 22nd, the annual nationwide charity tour will circle the US, presenting the best bands in music today while raising funds and awareness for Sex, Etc. and the concept that we can all play a part in making a positive impact in the world. -

Texas Public Schools and Charters, Directory, October 2007

Texas Public Schools and Charters, Directory, October 2007 2006-07 Appraised Tax rate Mailing address Cnty.-dist. Sch. County and district enroll- valuation Main- County, district, region, school and phone number number no. superintendents, principals Grades ment (thousands) tenance Bond 001 ANDERSON 001 CAYUGA ISD 07 P O BOX 427 001-902 DR RICK WEBB 570 $298,062 .137 .000 CAYUGA 75832-0427 PHONE - (903) 928-2102 FAX - (903) 928-2646 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL CAYUGA H S (903) 928-2294 001 DANIEL SHEAD 9-12 165 CAYUGA MIDDLE (903) 928-2699 041 SHERRI MCINNIS 6-8 133 CAYUGA EL (903) 928-2295 103 TRACIE CAMPBELL EE-5 272 ELKHART ISD 07 301 E PARKER ST 001-903 DR JOSEPH GLENN HAMBRICK 1321 $162,993 .137 .000 ELKHART 75839-9701 PHONE - (903) 764-2952 FAX - (903) 764-2466 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL ELKHART H S (903) 764-5161 001 TIMOTHY JOHN RATCLIFF 9-12 362 ELKHART MIDDLE (903) 764-2459 041 JAMES RONALD MAYS JR 6-8 287 ELKHART EL (903) 764-2979 101 MIKE MOON EE-5 672 DAEP INSTRUCTIONAL ELKHART DAEP 002 KG-12 0 FRANKSTON ISD 07 P O BOX 428 001-904 AUSTIN THACKER 789 $251,587 .133 .006 FRANKSTON 75763-0428 PHONE - (903) 876-2556 ext:222 FAX - (903) 876-4558 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL FRANKSTON H S (903) 876-3219 001 NICCI COOK 9-12 248 FRANKSTON MIDDLE (903) 876-2215 041 CHRIS WHITE 6-8 188 FRANKSTON EL (903) 876-2214 102 MARY PHILLIPS PK-5 353 NECHES ISD 07 P O BOX 310 001-906 RANDY L SNIDER 353 $72,781 .137 .000 NECHES 75779-0310 PHONE - (903) 584-3311 FAX - (903) 584-3686 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL NECHES H S (903) 584-3443 002 JOE ELLIS 7-12 138 NECHES EL -

La Joya High School U.I.L

La Joya High School U.I.L. Academic Student Letter 2019 – 2020 Dear Student, First of all, welcome to the 2019 – 2020 school year. Thank you for signing up to be a part of our UIL family. We are looking forward to starting the school year strong and ending with several UIL state champions. If we want to make this possible, it is very important that we start practicing as soon as possible, so stop by your coach’s class to obtain your sponsor’s information. They will then let you know when and where practice is going to be held and which meets we are going to. The following is a list of all the UIL meets that will take place during the 2019 – 2020 school year: 1. Saturday, October 19, 2019- Economedes High School 2. Saturday, November 2, 2019- Sharyland High School 3. Saturday, November 9, 2019 – La Joya High School (LJHS students do not compete) 4. Saturday, December 7, 2019 – Mission Veterans High School 5. Saturday, January 11, 2020– McAllen High School 6. Saturday, January 18, 2020- Palmview High School 7. Saturday, February 1, 2020 – Edinburg Vela High School 8. Saturday, February 15, 2020 – Mission High School 9. Saturday, February 22, 2020- Sharyland Pioneer High School 10. Saturday, February 29, 2020- Edinburg North High School 11. Saturday, March 7, 2020- La Joya ISD Pre-District (LJHS students do not compete) 12. Saturday, March 20-21, 2020– TMSCA State Meet San Antonio** 13. Saturday, March 28, 2020– 30-6A District Meet @ Mission Collegiate High School 14. Saturday, April 17-19, 2020– U.I.L. -

Documenttype# of #Meetingtype# Meeting

Agenda of Regular The Board of Trustees McAllen Independent School District VISION The McAllen Independent School District is a multicultural community in which students are enthusiastically and actively engaged in the learning process. Students demonstrate academic excellence in a safe, nurturing and challenging environment enhanced by technology and the contributions of the total community. MISSION The mission of the McAllen Independent School District is to educate all students to become lifelong learners and productive citizens in a global society through a program of educational excellence utilizing technology and actively involving parents and the community. GOALS 1. Student Achievement/Student Focus 2. People Development 3. Facility Priorities 4. Financial Priorities STRATEGIES 1. Branding 2. Attract/Retain High Quality Staff 3. Engaging Learning Environment 4. Rigorous/World Class Standards to Customize for Every Learner 5. Partnerships with Business/Civic/Education/Organizations 6. Future Ready Students 7. Financial Priorities A Regular of the Board of Trustees of the McAllen Independent School District will be held Monday, August 22, 2011, beginning at 5:00 PM in the Board Room/Administration Building of the McAllen Independent School District, 2000 North 23rd Street, McAllen, TX 78501. At this meeting there may be discussion and action by the Board on the item(s) and subject(s) listed as follows: Items listed on this agenda may be taken in an order other than as shown on this agenda. Unless removed from the consent agenda, items identified within the consent agenda will be acted on at one time. Attention: The regular business portion of the meeting for the public, beginning with agenda item #4, will begin at approximately 6:00 p.m. -

School Performance Review El Paso Letter of Transmittal 1999

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL March 29, 1999 The Honorable George W. Bush The Honorable Rick Perry The Honorable James E. "Pete" Laney Members of the Texas Legislature Commissioner Michael A. Moses, Ed.D. Ladies and Gentlemen: I am pleased to present our performance review of the El Paso Independent School District (EPISD). This review, requested by EPISD's superintendent and endorsed by Senator Eliot Shapleigh, is intended to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the district's operations by identifying problem areas and recommending innovative improvements. To aid in this task, the Comptroller's office contracted with Empirical Management Services, a Houston-based consulting firm. We have made a number of recommendations to improve EPISD's efficiency, but we also found a number of "best practices" in district operations. This report highlights several model programs and services provided by EPISD's administrators, teachers, and staff. Our primary goal is to help EPISD hold the line on costs, streamline operations, and improve services to ensure that every possible tax dollar is spent in the classroom teaching the district's children. This report outlines 142 detailed recommendations that could save EPISD $27.9 million over the next five years, while reinvesting $14.9 million to improve educational services and other operations. We are grateful for the cooperation of EPISD's administrators and employees, and we commend them and the community for their dedication to improving the educational opportunities offered to the children of El Paso. Sincerely, Carole Keeton Rylander Comptroller of Public Accounts Executive Summary In September 1998, the Comptroller's office conducted a performance review of the El Paso Independent School District (EPISD) at the request of the superintendent. -

Curriculum Vitae GEORGE D

Curriculum Vitae GEORGE D. DI GIOVANNI Professor, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Center for Infectious Diseases Department of Epidemiology, Human Genetics and Environmental Sciences University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health El Paso Campus 1101 N. Campbell CH 412, El Paso, Texas 79902 Phone: 915-747-8509 Fax: 915-747-8512 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Appointment with UTSPH: October 1, 2011 Dr. George D. Di Giovanni is Professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health, El Paso Campus. His research program specializes in the detection, infectivity determination, and molecular analysis of waterborne pathogens. Current research includes the quantitative molecular detection of protozoan, viral and bacterial pathogens; assessment of the efficacy of ultraviolet light disinfection of drinking water and wastewater; microbiological safety of reclaimed water; and microbial source tracking to determine the human and animal sources of fecal pollution of water supplies. He has received United States and European patents for methods and kits for the molecular detection of the parasite Cryptosporidium in water. He has served as Technical Laboratory Auditor for Environmental Protection Agency Method 1623, Detection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Water, in support of the Safe Drinking Water Act. His research has been funded by the Water Research Foundation (formerly the American Water Works Association Research Foundation); Environmental Protection Agency; United Kingdom Drinking Water Inspectorate; Drinking Water Quality Regulator for Scotland; Ecowise Environmental (Australia); Texas Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation; Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board; Texas Commission on Environmental Quality; Brazos River Authority; and the Paso del Norte Health Foundation – Center for Border Health Research. -

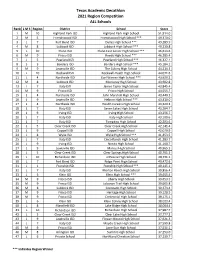

2020-2021 State Scores

Texas Academic Decathlon 2021 Region Competition ALL Schools Rank L M S Region District School Score 1M 10 Highland Park ISD Highland Park High School 51,914.0 2M 5 Friendswood ISD Friendswood High School *** 49,370.0 3L 7 Fort Bend ISD Dulles High School *** 49,289.9 4M 8 Lubbock ISD Lubbock High School *** 49,230.8 5L 10 Plano ISD Plano East Senior High School *** 46,613.6 6M 9 Frisco ISD Reedy High School *** 46,385.4 7L 5 Pearland ISD Pearland High School *** 46,327.1 8S 3 Bandera ISD Bandera High School *** 45,184.1 9M 9 Lewisville ISD The Colony High School 44,214.3 10 L 10 Rockwall ISD Rockwall‐Heath High School 44,071.6 11 L 4 Northside ISD Earl Warren High School *** 43,929.2 12 M 8 Lubbock ISD Monterey High School 43,902.8 13 L 7 Katy ISD James Taylor High School 43,845.4 14 M 9 Frisco ISD Frisco High School 43,555.7 15 L 4 Northside ISD John Marshall High School 43,440.3 16 L 9 Lewisville ISD Hebron High School *** 43,410.0 17 L 4 Northside ISD Health Careers High School 43,320.3 18 L 7 Katy ISD Seven Lakes High School 43,264.7 19 L 9 Irving ISD Irving High School 43,256.7 20 L 7 Katy ISD Katy High School 43,109.6 21 L 7 Katy ISD Tompkins High School 42,203.6 22 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Creek High School 42,141.4 23 L 9 Coppell ISD Coppell High School 42,070.9 24 L 8 Wylie ISD Wylie High School *** 41,453.5 25 L 7 Katy ISD Cinco Ranch High School 41,283.7 26 L 9 Irving ISD Nimitz High School 41,160.7 27 L 9 Lewisville ISD Marcus High School 40,965.3 28 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Springs High School 40,761.3 29 L 10 Richardson -

How to Play Metalcore on Guitar

How to Play Metalcore on Guitar And Getting Familiar with the Genre A Matura Paper by Yannic Kuna, 2013/2014 In collaboration with Beat Hüppin www.metalcoreonguitar.wordpress.com Contents 1. Acknowledgement ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 3. What is Metalcore? .............................................................................................................................. 5 4. August 2010 (about the author)................................................................................................... 7 5. Before it starts ....................................................................................................................................... 8 5.1 Guitar ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 5.2 Pick (Plectrum) ...................................................................................................................................... 10 5.3 Metronome .............................................................................................................................................. 10 5.4 Tuning ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Civil War in the Lone Star State

page 1 Dear Texas History Lover, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. It has a mystique that no other state and few foreign countries have ever equaled. Texas also has the distinction of being the only state in America that was an independent country for almost 10 years, free and separate, recognized as a sovereign gov- ernment by the United States, France and England. The pride and confidence of Texans started in those years, and the “Lone Star” emblem, a symbol of those feelings, was developed through the adventures and sacrifices of those that came before us. The Handbook of Texas Online is a digital project of the Texas State Historical Association. The online handbook offers a full-text searchable version of the complete text of the original two printed volumes (1952), the six-volume printed set (1996), and approximately 400 articles not included in the print editions due to space limitations. The Handbook of Texas Online officially launched on February 15, 1999, and currently includes nearly 27,000 en- tries that are free and accessible to everyone. The development of an encyclopedia, whether digital or print, is an inherently collaborative process. The Texas State Historical Association is deeply grateful to the contributors, Handbook of Texas Online staff, and Digital Projects staff whose dedication led to the launch of the Handbook of Civil War Texas in April 2011. As the sesquicentennial of the war draws to a close, the Texas State Historical Association is offering a special e- book to highlight the role of Texans in the Union and Confederate war efforts. -

Ktep-Fm of the University of Texas at El Paso Financial

KTEP-FM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO FINANCIAL STATEMENTS WITH INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT YEARS ENDED AUGUST 31, 2017 AND 2016 KTEP-FM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO FOR THE YEARS ENDED AUGUST 31, 2017 AND 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Independent Auditor's Report .................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion and Analysis ............................................ 3 Financial Statements ........................................................... 8 Statements of Net Position . .............................................. 9 Statements of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Position .................. 10 Statements of Cash Flows ................................................. 11 Notes to the Financial Statements ................................................. 12 Supplementary Information .................................................... 21 Schedules of Functional Expenses .......................................... 22 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS -3- KTEP-FM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS AUGUST 31, 2017 AND 2016 Introduction and Reporting Entity This discussion and analysis of KTEP-FM (“KTEP”), a public radio station operated by the University of Texas at El Paso (“UTEP”), provides an overview of KTEP’s financial activities during the year ended August 31, 2017. KTEP is the strongest public radio station in the El Paso market, serving El Paso and the surrounding areas up to 100 miles in radius. In addition to many local programs targeted specifically towards the El Paso community, KTEP also broadcasts news, cultural, and educational programs from National Public Radio and Public Radio International, as well as other independent radio networks. In addition to serving the El Paso community, KTEP also serves as a laboratory for broadcast students. KTEP is supported in part by the University of Texas at El Paso, which provides space for the station on campus, and pays the salaries of most of the full-time employees.