Of SANAA's Architecture, the Apparent Simplicity Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Book : “HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert Landon Featuring Projects by Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, and Many Others, All Photographed As Never Before. A Groundbreaking New book of Architectural Photographs and Original Essays Takes Readers on a Fascinating Journey Through Time In a visually striking new book Here/After: Structures in Time, award-winning photographer Paul Clemence and author Robert Landon take the reader on a remarkable tour of the hidden fourth dimension of architecture: Time. "Paul Clemence’s photography and Robert Landon’s essays remind us of the essential relationship between architecture, photography and time," writes celebrated architect, critic and former MoMA curator Terence Riley in the book's introduction. The 38 photographs in this book grow out of Clemence's restless search for new architectural encounters, which have taken him from Rio de Janeiro to New York, from Barcelona to Cologne. In the process he has created highly original images of some of the world's most celebrated buildings, from Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum to Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao. Other architects featured in the book include Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, I.M. Pei, Studio Glavovic, Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel. However, Clemence's camera also discovers hidden beauty in unexpected places—an anonymous back alley, a construction site, even a graveyard. The buildings themselves may be still, but his images are dynamic and alive— dancing in time. Inspired by Clemence's photos, Landon's highly personal and poetic essays take the reader on a similar journey. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

Kazuyo Sejima, Born in 1956 in the Prefecture of Ibaraki, Studied Architecture at the Japan Women's University, Graduating with a Master's Degree

Kazuyo Sejima, born in 1956 in the prefecture of Ibaraki, studied architecture at the Japan Women's University, graduating with a master's degree. She then joined the bureau of Toyo Ito. In 1987, she set up her own firm Kazuyo Sejima & Associates in Tokyo. Her early buildings already attracted attention, demonstrating not only elegance in form and material composition but also and above all her completely independent design approach. The young Japanese architect works on the basis of an abstract description of the uses and purposes of each particular building, transferring these into a spatial diagram and converting this diagram into architecture. This results in equally unusual and impressive buildings, which seem to confound all conventional typology, but remain closely related to their function. In this way, Kazuyo Sejima once again takes up the threads of the Modernism, but with an unorthodox, contemporary new interpretation of its premises and claims. In contrast to her teacher Ito and most of his generation, she is not concerned with reflecting or even increasing the fleetingness of the contemporary, but far more with a contemplative deceleration, which is without any kind of nostalgia. Earlier examples of this are the three house projects produced between 1988 and 1990, simply called PLATFORM I, PLATFORM II and PLATFORM III. With the Saishunkan Seljyku Women's Dormitory from 1991, for the first time she demonstrated the implementation of a complex programme into an equally irritating and refined architecturally aesthetic approach. The three Pachinko Parlors, created between 1993 and 1996 and numbered like the PLATFORM houses to declare the serial and continuous nature of the principal architectural research behind them, are essentially functionally neutral structures, whose elegance betrays the signature of their author throughout. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Mcmorrough John Cv Expanded Format

John McMorrough CV (September 2013) - 1/5 John McMorrough Associate Professor of Architecture University of Michigan / Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning 2000 Bonisteel Boulevard, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2069 Education Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Planning 2007, June Harvard University Dissertation: Signifying Practices: The Pre-Texts of Post-Modern Architecture (Advisors: M. Hays, S. Whiting, R. Somol) Master of Architecture (with Distinction) 1998, June Harvard University, Graduate School of Design Thesis: “Shopping and as the City”, Harvard Project on the City: Shopping (Advisor: R. Koolhaas) Bachelor of Architecture 1992, June University of Kansas, School of Architecture and Urban Design Exchange Student in Architecture: Universität Dortmund, Germany 9/88-6/89 Donald P. Ewart Memorial Traveling Scholarship 1988 Academic University of Michigan Associate Professor of Architecture, with tenure 9/2010 -... Chair, Architecture Program 2010-2013 Director, PhD in Architecture Degree 2010-2012 413: History of Architecture and Urbanism ("A Disciplinary Genealogy from 5,000 BC to 2010") (x3) 2011-2013 503: Special Topics in Architectural History ("Possible Worlds") 2013 506: Special Topics In Design Fundamentals ("Color Theory") 2013 322: Architectural Design II ("For Architecture, Five Projects" - Coordinator) 2011 University of Illinois at Chicago Greenwall Visiting Critic (Lectures, "Critical Figures: Reading Architecture Criticism") 2012 University of Applied Arts, Vienna Critic, Urban Strategies Post-Graduate Program (x4) 2008 - 2011 (08: Networks, 09: Game Space, 10: Brain City, 11: Porosity) Ohio State University Head, Architecture Section 2009 - 2010 Chair, Graduate Studies in Architecture 2008 - 2009 Associate Professor of Architecture, with tenure 2009 - 2010 Assistant Professor of Architecture 2005 - 2009 Charles E. -

Introduction Association (AA) School Where She Was Awarded the Diploma Prize in 1977

Studio London Zaha Hadid, founder of Zaha Hadid Architects, was awarded the Pritzker 10 Bowling Green Lane Architecture Prize (considered to be the Nobel Prize of architecture) in 2004 and London EC1R 0BQ is internationally known for her built, theoretical and academic work. Each of T +44 20 7253 5147 her dynamic and pioneering projects builds on over thirty years of exploration F +44 20 7251 8322 and research in the interrelated fields of urbanism, architecture and design. [email protected] www.zaha-hadid.com Born in Baghdad, Iraq in 1950, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London in 1972 to attend the Architectural Introduction Association (AA) School where she was awarded the Diploma Prize in 1977. She founded Zaha Hadid Architects in 1979 and completed her first building, the Vitra Fire Station, Germany in 1993. Hadid taught at the AA School until 1987 and has since held numerous chairs and guest professorships at universities around the world. She is currently a professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and visiting professor of Architectural Design at Yale University. Working with senior office partner, Patrik Schumacher, Hadid’s interest lies in the rigorous interface between architecture, landscape, and geology as her practice integrates natural topography and human-made systems, leading to innovation with new technologies. The MAXXI: National Museum of 21st Century Arts in Rome, Italy and the London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympic Games are excellent manifestos of Hadid’s quest for complex, fluid space. Previous seminal buildings such as the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati and the Guangzhou Opera House in China have also been hailed as architecture that transforms our ideas of the future with new spatial concepts and dynamic, visionary forms. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 226/Monday, November 23, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 226 / Monday, November 23, 2020 / Notices 74763 antitrust plaintiffs to actual damages Fairfax, VA; Elastic Path Software Inc, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE under specified circumstances. Vancouver, CANADA; Embrix Inc., Specifically, the following entities Irving, TX; Fujian Newland Software Antitrust Division have become members of the Forum: Engineering Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, CHINA; Notice Pursuant to the National Communications Business Automation Ideas That Work, LLC, Shiloh, IL; IP Cooperative Research and Production Network, South Beach Tower, Total Software S.A, Cali, COLOMBIA; Act of 1993—Pxi Systems Alliance, Inc. SINGAPORE; Boom Broadband Limited, KayCon IT-Consulting, Koln, Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM; GERMANY; K C Armour & Co, Croydon, Notice is hereby given that, on Evolving Systems, Englewood, CO; AUSTRALIA; Macellan, Montreal, November 2, 2020, pursuant to Section Statflo Inc., Toronto, CANADA; Celona CANADA; Mariner Partners, Saint John, 6(a) of the National Cooperative Technologies, Cupertino, CA; TelcoDR, CANADA; Millicom International Research and Production Act of 1993, Austin, TX; Sybica, Burlington, Cellular S.A., Luxembourg, 15 U.S.C. 4301 et seq. (‘‘the Act’’), PXI CANADA; EDX, Eugene, OR; Mavenir Systems Alliance, Inc. (‘‘PXI Systems’’) Systems, Richardson, TX; C3.ai, LUXEMBOURG; MIND C.T.I. LTD, Yoqneam Ilit, ISRAEL; Minima Global, has filed written notifications Redwood City, CA; Aria Systems Inc., simultaneously with the Attorney San Francisco, CA; Telsy Spa, Torino, London, UNITED KINGDOM; -

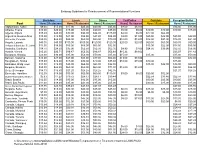

Embassy Guidelines for Reimbursement of Representational Functions

Embassy Guidelines for Reimbursement of Representational Functions Breakfast Lunch Dinner Tea/Coffee Cocktails Reception/Buffet Post Home Restaurant Home Restaurant Home Restaurant Home Restaurant Home Restaurant Home Restaurant Afghanistan, Kabul $9.00 $15.00 $17.00 $25.00 $20.00 $35.00 $8.00 $12.00 $14.00 $15.00 Albania, Tirana $10.00 $20.00 $15.00 $30.00 $20.00 $35.00 $5.00 $5.00 $10.00 $10.00 $10.00 $15.00 Algeria, Algiers $18.00 $40.00 $30.00 $90.00 $44.00 $125.00 $4.00 $6.00 $22.00 $64.00 Argentina, Buenos Aires $15.00 $18.50 $47.00 $54.00 $47.00 $54.00 $8.00 $11.00 $25.00 $42.00 $25.00 $42.00 Armenia, Yerevan $20.00 $22.00 $25.00 $60.00 $40.00 $70.00 $10.00 $12.00 $16.00 $21.00 $16.00 $21.00 Angola, Luanda $40.00 $40.00 $100.00 $100.00 $120.00 $120.00 $20.00 $20.00 $60.00 $60.00 $60.00 $50.00 Antigua & Barduda, St. Johns $11.00 $18.00 $45.00 $66.00 $63.00 $92.00 $15.00 $22.00 $34.00 $45.00 Australia, Canberra $14.70 $24.50 $35.00 $52.50 $52.50 $62.30 $4.90 $7.00 $24.50 $39.90 $52.50 $56.00 Austria, Vienna $15.26 $20.71 $46.87 $56.56 $46.87 $56.68 $15.26 $19.62 $25.07 $41.42 Bahamas, Nassau $20.00 $30.00 $35.00 $50.00 $70.00 $85.00 $15.00 $15.00 $15.00 $50.00 Bahrain, Manama $13.00 $27.00 $27.00 $53.00 $37.00 $66.00 $13.00 $19.00 $19.00 $32.00 Bangladesh, Dhaka $15.00 $20.00 $15.00 $30.00 $20.00 $35.00 $10.00 $15.00 $10.00 $15.00 Barbados, Bridgetown $11.00 $18.00 $45.00 $66.00 $63.00 $92.00 $15.00 $22.00 $34.00 $50.00 Belguim, Brussels $28.00 $28.00 $60.00 $60.00 $60.00 $71.00 $12.00 $12.00 $24.00 $24.00 Belize,Belmopan $14.10 -

The Things They've Done : a Book About the Careers of Selected Graduates

The Things They've Done A book about the careers of selected graduates ot the Rice University School of Architecture Wm. T. Cannady, FAIA Architecture at Rice For over four decades, Architecture at Rice has been the official publication series of the Rice University School of Architecture. Each publication in the series documents the work and research of the school or derives from its events and activities. Christopher Hight, Series Editor RECENT PUBLICATIONS 42 Live Work: The Collaboration Between the Rice Building Workshop and Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas Nonya Grenader and Danny Samuels 41 SOFTSPACE: From a Representation of Form to a Simulation of Space Sean tally and Jessica Young, editors 40 Row: Trajectories through the Shotgun House David Brown and William Williams, editors 39 Excluded Middle: Toward a Reflective Architecture and Urbanism Edward Dimendberg 38 Wrapper: 40 Possible City Surfaces for the Museum of Jurassic Technology Robert Mangurian and Mary-Ann Ray 37 Pandemonium: The Rise of Predatory Locales in the Postwar World Branden Hookway, edited and presented by Sanford Kwinter and Bruce Mau 36 Buildings Carios Jimenez 35 Citta Apperta - Open City Luciano Rigolin 34 Ladders Albert Pope 33 Stanley Saitowitz i'licnaei Bell, editor 26 Rem Koolhaas: Conversations with Students Second Editior Sanford Kwinter, editor 22 Louis Kahn: Conversations with Students Second Edition Peter Papademitriou, editor 11 I I I I I IIII I I fo fD[\jO(iE^ uibn/^:j I I I I li I I I I I II I I III e ? I I I The Things They've DoVie Wm. -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Djibouti

UNITED NATIONS HUMANITARIAN AIR SERVICE YEMEN WEEKLY FLIGHT SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE 15 FEB 2016 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Djibouti Djibouti Amman Djibouti Djibouti Sanaa Sanaa Sanaa Aden Sanaa Crew Rest Stand-by Djibouti Amman Djibouti Djibouti Djibouti Additional Important Information: Please send duly completed booking forms to [email protected] 1. Departure times may vary due to operational requirements. UNHAS Team Contact Details: 2. Latest booking submission is 72 hrs prior to departure. 3. Booking forms can be found at http://www.logcluster.org/document/passenger-movement-request-form UNHAS Chief : George Harb +967 73 789 1 240 4. Booking forms are to be submitted to: [email protected]. Sana'a : Rashed ALSAADI +967 735 477 740 5. The passenger's respective organization is responsible for security clearance and visa. Abdo Salem +967 73 3 232 190 6. Flight confirmation to passengers will be sent within 48 hrs prior to departure. 7. A "UN ceiling" may apply to all UN staff deployed in Yemen. Djibouti: Mr. Hordur Karlsson 8. Passengers are responsible for paying all applicable taxes at each airport. Alain DURIAU +253 77 22 41 21 9. All passengers should be at the airport 2 hrs before scheduled departure time. 10. All transit passengers should remain in the assigned transit areas. Amman: Bara’ al abbadi +962 79571007 11. Passengers travelling with UNHAS must be involved in humanitarian activities in Yemen. Family members/dependants are not eligible. 12. A letter of authorization from the requesting organization may be required for consultants/short-term contract holders. 13. -

Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S

118 Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S. Department of State Locations Embassy Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Dushanbe, Tajikistan Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Freetown, Sierra Leone Accra, Ghana Gaborone, Botswana Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Georgetown, Guyana Algiers, Algeria Guatemala City, Guatemala Almaty, Kazakhstan Hanoi, Vietnam Amman, Jordan Harare, Zimbabwe Ankara, Turkey Helsinki, Finland Antananarivo, Madagascar Islamabad, Pakistan Apia, Samoa Jakarta, Indonesia Ashgabat, Turkmenistan Kampala, Uganda Asmara, Eritrea Kathmandu, Nepal Asuncion, Paraguay Khartoum, Sudan Athens, Greece Kiev, Ukraine Baku, Azerbaijan Kigali, Rwanda Bamako, Mali Kingston, Jamaica Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Kinshasa, Democratic Republic Bangkok, Thailand of the Congo (formerly Zaire) Bangui, Central African Republic Kolonia, Micronesia Banjul, The Gambia Koror, Palau Beijing, China Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Beirut, Lebanon Kuwait, Kuwait Belgrade, Serbia-Montenegro La Paz, Bolivia Belize City, Belize Lagos, Nigeria Berlin, Germany Libreville, Gabon Bern, Switzerland Lilongwe, Malawi Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan Lima, Peru Bissau, Guinea-Bissau Lisbon, Portugal Bogota, Colombia Ljubljana, Slovenia Brasilia, Brazil Lomé, Togo Bratislava, Slovak Republic London, England, U.K. Brazzaville, Congo Luanda, Angola Bridgetown, Barbados Lusaka, Zambia Brussels, Belgium Luxembourg, Luxembourg Bucharest, Romania Madrid, Spain Budapest, Hungary Majuro, Marshall Islands Buenos Aires, Argentina Managua, Nicaragua Bujumbura, Burundi Manama, Bahrain Cairo, Egypt Manila, -

Kazuyo Sejima the Star Architect and Pritzker Prize Holder Will Teach Architecture Starting in October 2015

Kazuyo Sejima The star architect and Pritzker Prize holder will teach architecture starting in October 2015. “I am extremely pleased that the outstanding and innovative architect Kazuyo Sejima has agreed to teach at our university. The Pritzker Prize holder will take up her position as a visiting professor this coming October, initially for one semester,” relates Gerald Bast, Rector of the University of Applied Arts Vienna. In the fall of 2015, a professorial chair will be advertised and the appointment procedure will begin. The Japanese architect has received numerous prizes and awards in the course of her career to date, the highlight being the illustrious Pritzker Prize in 2010. The Pritzker jury’s citation described Sejima’s architecture as “simultaneously delicate and powerful, precise and fluid”. She is the second woman to have received this award, often spoken of as the “Nobel Prize of architecture”. The first was Zaha Hadid, who was honored with the Pritzker Prize in 2004. Hadid will become Professor Emeritus at the end of the summer semester, after fifteen successful years at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. The university will express its appreciation and bid her farewell at a special festive ceremony. Kazuyo Sejima was born in 1956 in Ibaraki, Japan. She concluded her studies in 1981 and, together with Ryue Nishizawa, founded the architecture firm SANAA in Tokyo in 1987. In 2010 she became the first woman to direct the Venice Architecture Biennale. Sejima’s clear designs are characterized by modernity and an exceptional understanding of the spatial experience. Her architecture firm SANAA builds mainly in a minimalist style, using, primarily, textured concrete, steel, aluminum, and glass.