The Increasing Invisibility of Special Leave to Appeal Applications In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinner Address the Law: Past and Present Tense Hon Justice Ian

Dinner Address The Law: Past and Present Tense Hon Justice Ian Callinan, AC I do not want to revisit the topic of judicial activism, a matter much debated in previous proceedings of this Society. But it is impossible to speak about the law as it was, as it is now, and as it may be in the future, without at least touching upon a number of matters: precedent, judicial activism, and whether and how a final court should inform itself, or be informed about shifts in social ways and expectations. To develop my theme I have created a piece of fiction. The law, as you all know, is no stranger to fictions. It is not the year 2003, it is not even the year 1997 when the High Court decided Lange v. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.1 It is the year 1937. Merely five years later Justice Learned Hand in the United States would observe: “The hand that rules the press, the radio, the screen, and the far-spread magazine, rules the country”. Only seventeen years earlier the High Court had decided the landmark Engineers’ Case.2 This, you may recall, was the case in which the Court held that if a power has been conferred on the Commonwealth by the Constitution, no implication of a prohibition against the exercise of that power can arise, nor can a possible abuse of the power narrow its limits. This was a revolutionary decision. It denied what had been thought to be settled constitutional jurisprudence, that the Commonwealth Parliament could not bind the Executive of a State in the absence of express words in s.51 of the Constitution to that effect. -

Autumn 2015 Newsletter

WELCOME Welcome to the CHAPTER III Autumn 2015 Newsletter. This interactive PDF allows you to access information SECTION NEWS easily, search for a specific item or go directly to another page, section or website. If you choose to print this pdf be sure to select ‘Fit to A4’. III PROFILE LINKS IN THIS PDF GUIDE TO BUTTONS HIGH Words and numbers that are underlined are COURT & FEDERAL Go to main contents page dynamic links – clicking on them will take you COURTS NEWS to further information within the document or to a web page (opens in a new window). Go to previous page SIDE TABS AAT NEWS Clicking on one of the tabs at the side of the Go to next page page takes you to the start of that section. NNTT NEWS CONTENTS Welcome from the Chair 2 Feature Article One: No Reliance FEATURE Necessary for Shareholder Class ARTICLE ONE Section News 3 Actions? 12 Section activities and initiatives Feature Article Two: Former employees’ Profile 5 entitlement to incapacity payments under the Safety, Rehabilitation and FEATURE Law Council of Australia / Federal Compensation Act 1988 (Cth) 14 ARTICLE TWO Court of Australia Case Management Handbook Feature Article Three: Contract-based claims under the Fair Work Act post High Court of Australia News 8 Barker 22 Practice Direction No 1 of 2015 FEATURE Case Notes: 28 ARTICLE THREE Judicial appointments and retirements Independent Commission against High Court Public Lecture 2015 Corruption v Margaret Cunneen & Ors [2015] HCA 14 CHAPTER Appointments Australian Communications and Media Selection of Judicial speeches -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Chapter Two Can Judges Resuscitate Federalism?

Chapter Two Can Judges resuscitate Federalism? John Gava* In a recent article Greg Craven has argued that we are in the “midst of an ideological struggle for the Constitution’s soul”,1 and that it would be appropriate to appoint an “Australian Scalia”2 to the High Court. Indeed, Craven argues that a conservative government would be “downright derelict in its duty”3 if it failed to make such an appointment. For Craven, the High Court has consistently, at least from 1920, interpreted the Australian Constitution with such a centralist bias that the original conception of a federation has been distorted.4 Craven has argued that by going down this centralist path the High Court has departed from the expectations of the founders of the Constitution, and that the role of putative Australian Justice Scalias would be to interpret our Constitution in light of the intentions of those founders. In this paper I carry out the equivalent of a thought experiment and consider what would happen if Craven were to get his wish of a High Court composed of judges willing to interpret the Constitution in the way in which he advocates—i.e., by giving effect to the original intentions of the founders, who conceived of a robust federation rather than the unbalanced, centrally dominated one that we have today. I will do this by analysing the dissenting judgments of Justices Kirby and Callinan in the Work Choices Case5 to show that both judges decide the constitutional issue before them, the validity of the Commonwealth’s Work Choices legislation, with an eye to reviving federalism as a substantive feature of the Constitution. -

In August 2008 I Was Fortunate Enough to Be Selected to Attend the Annual Samuel Griffith Society Conference in Sydney

In August 2008 I was fortunate enough to be selected to attend the annual Samuel Griffith Society Conference in Sydney. I had become interest in the Samuel Griffith Society ever since conducting research during my constitutional law studies. In particular I found interest in the papers from the 2006 Samuel Griffith Society Conference that discussed the Workchoices decision. The Workchoices decision extended the interpretation of the corporations power of the Constitution to allow the federal government to legislate in relation to employment conditions. This debate over the wider interpretation of the powers of the federal government occurred at the perfect time to extend my knowledge of constitutional law and in particular the history of the Australian constitution and the intention of the founding fathers when they drafted it. The Samuel Griffith Society promotes the preservation of the constitution to its initial purposes and disapproves of the widening of interpretation of the document to increase the powers of the federal government. I found it fascinating to see and hear an interest group dedicated to one purpose – the protection of the constitution. One of the most important cases I recall during my constitutional law studies was the Tasmanian Dam Case. The case found that the external powers of the Constitution allowed the federal government to legislate in regards to issues to which it had entered into agreement with internationally. I was lucky enough to be introduced to recently retired Justice of the High Court Ian Callinan. Callinan gave an introductory speech in memorial of former High Court Chief Justice Harry Gibbs who dissented in the decision of the Tasmanian Dam Case and was concerned with the potential danger it posed to the federal balance. -

UEENSLAND Polit EFORM GROUP

t Submission No: . L8. UEENSLAND POLiT EFORM GROUP hOUSESTANDINGOF p[p~(( ‘~x~..~; ~, 0738162120 Noel Turner LJ~GA±ANDAPPAJRSCONS P0 Box 563 Booval 4304 Submission ofcorrespondence copies as evidence of activity relating to: •:~ The shredding of the Heiner documents by the authority of the Queensland Government Executive on 23.3.1990, and the following cover-up to date ~• The Lindeberg Grievance submitted by the late MrRobert Greenwood QC This material is circulated to: •~ The H.ouse ofRepresentatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Afairs; “Crime in the Community” (Secretary Gillian Gould •~ The Australian Senate Select Committee on the Lindeberg Grievance (Secretary Alistair Sands ~• Professor Bruce Grundy, Department ofJournalism and Communications, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane. This material is organised in six (6) small folios covering the period from March 1996 (1993) to 1998. Each folio covers an initiative by us ( members of the Queensland Political Reform Group QPRG), and related responses to our initiatives, also supporting extracts of publications and public statements. The OPRG has as its objective , sound and just to all parties resolution of the events leading to the shredding of the Ileiner Inquiry Documents in Queensland on 23 -03 — 1990, and the following and continuing cover-up, and to have this conducted as a lawful and constitutional exercise by Queensland and AustralianPublic Institutions. ) Arrangement ofthe documents, and what they reveal 1. The first folio, docs 1 — 4 , show that OPRG was stating/supporting our view that only a specifically constituted Commission of Inquiry could competently examine the circumstances of the shredding of the Heiner Inquiry Documents, the following cover-up and political denials. -

The Changing Position and Duties of Company Directors

CRITIQUE AND COMMENT THE CHANGING POSITION AND DUTIES OF COMPANY DIRECTORS T HE HON JUSTICE GEOFFREY NETTLE* In 1974, in the first edition of his Principles of Company Law, Professor Ford was able to say that directors’ duties were ‘not very demanding’. This lecture traces how the duties and standards of care demanded of company directors have increased since then. In doing so, it makes reference to the attenuated business judgment rule, comparing the positions in the United Kingdom and, briefly, South Africa. It then considers similarities and differences between the duties imposed on company directors, union officers and public officials. It suggests that, while the regulatory regimes that apply to company directors and union officers are strikingly different, there is little reason in principle why that should be so. For practical reasons, the same cannot be said of the differences between public officials and company directors or union officers. But it remains somewhat paradoxical that, although the actions of public officials may have far more broad- ranging effects on the nation’s wellbeing than the actions of any company director or union officer, public officials’ duties are much less onerous. CONTENTS I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1403 II Directors’ Duties .................................................................................................... 1404 A The Development of Directors’ Duties in Equity ................................ -

Reflections on the Murphy Trials

REFLECTIONS ON THE MURPHY TRIALS NICHOLAS COWDERY AM QC∗ I INTRODUCTION It is a great privilege to have been asked to contribute to this special edition of the Journal containing essays in honour of the Honourable Ian Callinan AC QC.1 In this instance I shall concentrate on but one matter in his extensive practice at the Bar, but a significant matter that went for some time, had a variety of manifestations and encompassed a multitude of interests and conflicts: that is, his role as the prosecutor of the late Justice Lionel Murphy of the High Court of Australia. It is also a great burden to assume. Where to begin? What ‘spin’ (if any) to put on this chapter of Australia’s legal history in the space available? How much of the lengthy and at times legally technical proceedings themselves should be included? How to show enough of the play of the unique Callinan attributes? How to keep myself out of it, matters of significance having now faded from the ageing memory (even assisted by the few scraps of paper that survive) and because throughout the proceedings against Murphy at all levels I was Ian’s principal junior. It was a rare (for the time) pairing of Queensland and NSW counsel – the ‘dingo fence’ for lawyers was still in place at the Tweed in those days. At the time of his retirement from the High Court last year Ian described the case as ‘agonising’ – for himself, the court and Murphy – ‘It was a very unhappy time for everybody’ he said and so it was. -

The Australian Law Journal

Australian Law Journal GENERAL EDITOR Mr Justice P W Young PRODUCTION EDITOR Cheryle King ASSISTANT GENERAL EDITOR Dr Paul Gerber The mode of citation of this volume is (2003) 77 ALJ [page] Australian Law Journal Reports TEAM LEADER Carmel Jones PRODUCTION EDITOR Carolyn May CASE REPORTERS Lachlan Cottom Clare D'Arcy Cathie Dickinson Paul Govind Natalie Lammas Renu Prasad Angeline Wong The mode of citation of this volume is 77 ALJR [page] (2003) 77 ALJ 625625 © THE AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL Volume 77, Number 10 October 2003 CURRENT ISSUES – Editor: Mr Justice P W Young Centenary of the High Court ................................................................................................ 631 High Court dissents .............................................................................................................. 631 Gilbert & Tobin Centre of Public Law Constitutional Law Conference, 2003 .................... 632 Judicial review...................................................................................................................... 632 Victorian Bar Inc Annual Report.......................................................................................... 632 Law Council of Australia ..................................................................................................... 632 Publishing pornography........................................................................................................ 633 Victims and sentencing........................................................................................................ -

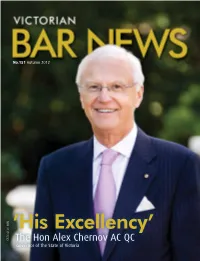

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Alumni News2005v11.Indd

POSTCARDS AND LETTERS HONOURS DEATHS (August 2003 – July 2005) OBITUARIES Alumni News Supplement to Trinity Update August 2005 Trinity College 2004 AUSTRALIA DAY HONOURS Dr Yvonne AITKEN, AM (1930) REGINALD LESLIE STOCK, OBE, COLIN PERCIVAL JUTTNER JOHN GORDON RUSHBROOKE THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Dr Nancy AUN (1976) 1909-2004 1910-2003 1936-2003 Hugh Wilson BALLANTYNE (1951) AC Reg Stock entered Trinity in 1929, studying for a Following in his father’s footsteps, Colin Juttner entered John Rushbrooke entered Trinity from Geelong Grammar in What a kaleidoscope of activities is reflected in this collection of news items, gathered since August 2003 from Peter BALMFORD (1946) Leonard Gordon DARLING (TC 1940), AO, CMG, combined Arts/Law degree. He was elected Secretary Trinity from St Peter’s College, Adelaide, in 1929 and 1954 with a General Exhibition. He completed his BSc in Alumni and Friends of Trinity College, the University of Melbourne. We hope this new trial format will help to Dr (William) Ronald BEETHAM, AM (1949) Melbourne, Victoria. For service to the arts through of the Fleur de Lys Club in 1932 and Senior Student enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. He took a prominent 1956, graduating with prizes in Mathematics and Physics. rekindle memories and prompt some renewed contacts, and apologise if any details have become dated. vision, advice and philanthropy for long-term benefit Dr Garry Edward Wilbur BENNETT (1938) in 1933. As such he chaired the meeting of the Club part in student life, representing the College in cricket His Master’s degree saw him begin his work as a high to the nation. -

Judges and Retirement Ages

JUDGES AND RETIREMENT AGES ALYSIA B LACKHAM* All Commonwealth, state and territory judges in Australia are subject to mandatory retirement ages. While the 1977 referendum, which introduced judicial retirement ages for the Australian federal judiciary, commanded broad public support, this article argues that the aims of judicial retirement ages are no longer valid in a modern society. Judicial retirement ages may be causing undue expense to the public purse and depriving the judiciary of skilled adjudicators. They are also contrary to contemporary notions of age equality. Therefore, demographic change warrants a reconsideration of s 72 of the Constitution and other statutes setting judicial retirement ages. This article sets out three alternatives to the current system of judicial retirement ages. It concludes that the best option is to remove age-based limitations on judicial tenure. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 739 II Judicial Retirement Ages in Australia ................................................................... 740 A Federal Judiciary .......................................................................................... 740 B Australian States and Territories ............................................................... 745 III Criticism of Judicial Retirement Ages ................................................................... 752 A Critiques of Arguments in Favour of Retirement Ages ........................