Consolidation in Local Government: a Fresh Look 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redistribution of New South Wales Into Electoral Divisions FEBRUARY 2016

Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions FEBRUARY 2016 Report of the augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in 18 languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-44-2 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 © State of New South Wales 2016 The report should be cited as augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales, Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions. 15_0526 The augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales (the augmented Electoral Commission) has undertaken a redistribution of New South Wales. In developing and considering the impacts of the redistribution, the augmented Electoral Commission has satisfied itself that the electoral divisions comply with the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The augmented Electoral Commission commends its redistribution for New South Wales. This report is prepared to fulfil the requirements of section 74 of the Electoral Act. -

Australia's Gambling Industries 3 Consumption of Gambling

Australia’s Gambling Inquiry Report Industries Volume 3: Appendices Report No. 10 26 November 1999 Contents of Volume 3 Appendices A Participation and public consultation B Participation in gambling: data tables C Estimating consumer surplus D The sensitivity of the demand for gambling to price changes E Gambling in indigenous communities F National Gambling Survey G Survey of Clients of Counselling Agencies H Problem gambling and crime I Regional data analysis J Measuring costs K Recent US estimates of the costs of problem gambling L Survey of Counselling Services M Gambling taxes N Gaming machines: some international comparisons O Displacement of illegal gambling? P Spending by problem gamblers Q Who are the problem gamblers? R Bankruptcy and gambling S State and territory gambling data T Divorce and separations U How gaming machines work V Use of the SOGS in Australian gambling surveys References III Contents of other volumes Volume 1 Terms of reference Key findings Summary of the report Part A Introduction 1 The inquiry Part B The gambling industries 2 An overview of Australia's gambling industries 3 Consumption of gambling Part C Impacts 4 Impacts of gambling: a framework for assessment 5 Assessing the benefits 6 What is problem gambling? 7 The impacts of problem gambling 8 The link between accessibility and problems 9 Quantifying the costs of problem gambling 10 Broader community impacts 11 Gauging the net impacts Volume 2 Part D The policy environment 12 Gambling policy: overview and assessment framework 13 Regulatory arrangements for major forms of gambling 14 Are constraints on competition justified? 15 Regulating access 16 Consumer protection 17 Help for people affected by problem gambling 18 Policy for new technologies 19 The taxation of gambling 20 Earmarking 21 Mutuality 22 Regulatory processes and institutions 23 Information issues IV V A Participation and public consultation The Commission received the terms of reference for this inquiry on 26 August 1998. -

Implementation Strategies for a Heritage Trail That Would Link the Great Southern Shires in Western Australia

PROJECT # 31009 Implementation strategies for a heritage trail that would link the Great Southern Shires in Western Australia The “Heritage of Endeavour” project. By Michael Hughes and Jim Macbeth ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, we acknowledge the contribution of Lindley Chandler to this final report. Lindley undertook this project as part of her Masters degree and carried out all of the basic ground work and community consultation. Unfortunately, due to ill health, Lindley was unable to write the final report. Nonetheless, the report is based on her work in the Central Great Southern. Russell Pritchard, Regional Officer with the Great Southern Development Commission, provided invaluable advice and support in further developing and crystallising the ideas within this report. Many other Central Great Southern community members contributed information as detailed in the reference list at the end of the report. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre, an Australian Government initiative, in funding this project. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Recommended Tourism Developments 3 Drive Trails 3 Conclusion 3 Recommended Tourism Drive Trails and Attractions Descriptions 6 Tourism Drive Trail Runs 6 Drive trail #1: The Central Great Southern Run 6 Drive Trail #2: The Pingrup Run 14 Drive Trail #3: The Stirlings Run 18 Drive Trail #4: The Malleefowl Run 20 Drive Trail # 5: The Chester Pass Run 20 Drive Trail #6: The Salt River Rd Run 21 Drive Trail #7: The Bluff Knoll Run 24 Drive Trail #8: The Perth Scenic Run 25 Drive Trail #9: The Olives and Wine Run. 26 Tourism Drive Trail Day Loops 27 Drive Trail #10: Great Southern Wine Loop 27 Drive Trail #11 Chester Pass Day Loop 27 Drive trail #12 Salt River Rd Day Loop 27 APPENDIX: Inventory of Tourism Sites 30 REFERENCES 40 AUTHORS 40 List of Plates Plate 1: Historic Church in the main street of Woodanilling. -

September BT Times 2017

VOLUME 10 1 ISSUEISSUE 11 1 OCTOBER 2008 SEPTEMBER 2017 Your local newsletter covering the Broomehill and Tambellup communities. LD300817/1 2 BT TIMES BT TIMES 3 SHIRE OF BROOMEHILL-TAMBELLUP Phone: 98253555 Fax: 98251152 Email: [email protected] The next meeting of Council will be held on Thursday 21st September 2017 commencing at 4.00pm in the Tambellup Council Chambers. Members of the public are welcome to attend all Council meetings. FROM THE COUNCIL MEETING WORKS Local contractors have completed the installation of Council approved an amendment to the Schedule of the new shade structure over the playground in Fees and Charges for the 2017/18 year to reflect Holland Park. The re-installation of swings into the amendments to Building Application fees as playground, which were removed for access, fencing prescribed under the Building Regulations 2011 and and sand soft fall is scheduled for the next week or effective from 1 July 2017. two. Council considered and approved requests from the Funding received from the Southern Inland Health Tambellup Golf Club and the Tambellup Business Initiative has enabled construction of pram ramps Centre to grant concessions on the rate charges for linking footpaths in both town centres. Three have the 2017/18 financial year. The Tambellup Golf Club been completed in Broomehill, and the remainder in remains the only sporting organisation within the Tambellup will be completed in coming months. Broomehill-Tambellup Shire that has Council rates levied against it. The Tambellup Business Centre is a Both ovals have recently been fertilised and sprayed not for profit organisation that provides training and for broadleaf weeds. -

Service Plan: Central Great Southern Health District (2011/12 – 2021/22)

SERVICE PLAN: CENTRAL GREAT SOUTHERN HEALTH DISTRICT (2011/12 – 2021/22) Endorsed 26 September 2012 Corporate Details Project Leader Jo Thorley Aurora Projects Pty Ltd ABN 81 003 870 719 Suite 20, Level 1, Co-authors 111 Colin Street, West Perth, WA 6005 T + 61 8 9254 6300 Leeann Murphy, Aurora Projects F + 61 8 9254 6301 Nancy Bineham, Country Health Services Central Office www.auroraprojects.com.au Beth Newton, Country Health Services Central Office Nerissa Wood, Country Health Services Central Office SCHS Great Southern Regional Executive Members Central Great Southern District Services Plan, Southern Country Health Service SIGNATORY PAGE Central Great Southern District Services Plan, Southern Country Health Service i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction ................................................................................................. 8 3 Planning Context and Strategic Directions ............................................... 9 3.1 SCHS Great Southern current services .............................................................. 9 3.2 Central Great Southern health service profile ..................................................... 10 3.3 Commonwealth and State government policies .................................................. 13 3.4 Planning initiatives and commitments ................................................................. 16 3.5 Strategic directions for service delivery .............................................................. -

Western Australia

115291 OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA (Published by Authority at 3 .30 p.m .) (REGISTERED AT THE GENERAL POST OFFICE, PERTH, FOR TRANSMISSION BY POST AS A NEWSPAPER) No. 35 ] PERTH : FRIDAY, 14th May [1971 Premier's Department, Education : Perth, 10th May, 1971 . Education . IT is hereby notified for public information that National Fitness . His Excellency the Governor has approved of the Public Education Endowment Act . following temporary allocation of portfolios :- Junior Farmers' Movement Act . During the absence overseas of the Hon. A. D. Country High Schools Hostels Authority . Taylor, B.A., M.L.A., from 19th May, 1971- Environmental Protection : The Honourable Ronald Edward Physical Environment Protection Act . Bertram, A.A.S.A., M.L.A., to be Acting Minister for Housing and Cultural Affairs . Labour. W. S. LONNIE, DEPUTY PREMIER, MINISTER FOR INDUS- Under Secretary, Premier's Department . TRIAL DEVELOPMENT AND DECENTRAL- ISATION, AND TOWN PLANNING . Industrial Development and Decentralisation : Premier's Department, Industrial Development (Kwinana Area) Act . Perth, 12th May, 1971 . Industrial Lands Development Authority Act . IT is hereby notified for public information that Iron and Steel Industry Act. His Excellency the Governor in Executive Council The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited has been pleased to approve of the administration (Export of Iron Ore) Act. of Departments, Statutes and Votes being placed Wood Distillation and Charcoal Iron and Steel under the control of the respective Ministers as Industry Act . set out hereunder :- Alumina Refinery Agreement Act . Alumina Refinery (Bunbury) Agreement Act . PREMIER, MINISTER FOR EDUCATION, EN- Alumina Refinery (Mitchell Plateau) Agree- VIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND CUL- ment Act . TURAL AFFAIRS. -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 126 Friday 5 May 2006 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer ROAD SAFETY (VEHICLES) REGULATIONS 1999 Class 2 Notice – Conditional Exemption of Heavier and Longer B-doubles with Road Friendly Suspension from Certain Mass Limits 1. Purpose To exempt certain class 2 vehicles from certain mass and dimension limits subject to complying with certain conditions. 2. Authorising provision This Notice is made under regulation 510 of the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999. 3. Commencement This Notice comes into operation on the date of its publication in the Government Gazette. 4. Revocation The Notices published in Government Gazette No. S134 of 17 June 2004 and Government Gazette No. S236 of 25 November 2005 are revoked. 5. Expiration This Notice expires on 1 March 2011. 6. Definitions In this Notice – “Regulations” means the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999. “road friendly suspension” has the same meaning as in the Interstate Road Transport Regulations 1986 of the Commonwealth. “Approval Plate” means a decal, label or plate issued by a Competent Entity that is made of a material and fixed in such a way that they cannot be removed without being damaged or destroyed and that contains at least the following information: (a) Manufacturer or Trade name or mark of the Front Underrun Protection Vehicle, or Front Underrun Protection Device, or prime mover in the case of cabin strength, or protrusion as appropriate; (b) In the case of a Front Underrun Protection Device or protrusion, the make of the vehicle or vehicles and the model or models of vehicle the component or device has been designed and certified to fit; (c) Competent Entity unique identification number; (d) In the case of a Front Underrun Protection Device or protrusion, the Approval Number issued by the Competent Entity; and (e) Purpose of the approval, e.g. -

House of Representatives

vii 1946-47-48. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FIRST SESSION OF THE EIGHTEENTH PARLIAMENT. (Sittings-From6th November, 1946, to 18th June, 1948.) (Parliamentprorogued 4th August, 1948.) [NOTE.-For return of Voting at General Election, see Parliamentary Paper No. 12 of Session 1948-49, Vol. V., p. 137.] Name. Division. State. Abbott, Hon. Joseph Palmer, M.C. New England New South Wales Adermann, Charles Frederick, Esquire Maranoa . Queensland Anthony, Hon. Hubert Lawrence Richmond . New South Wales Barnard, Hon. Herbert Claude .. Bass Tasmania Beale, Oliver Howard, Esquire .. Parramatta New South Wales Beazley, Kim Edward, Esquire .. Fremantle . Western Australia Blackburn, Mrs. Doris Amelia Bourke Victoria Blain, Adair Macalister, Esquire Northern Territory Bowden, George James, Esquire, M.C. Gippsland Victoria Brennan, Hon. Frank .. Batman Victoria Burke, Thomas Patrick, Esquire Perth Western Australia Calwell, Hon. Arthur Augustus .. Melbourne Victoria Cameron, Hon. Archie Galbraith Barker South Australia Chambers, Hon. Cyril . Adelaide South Australia Chifley, Rt. Hon. Joseph Benedict Macquarie.. New South Wales Clark, Joseph James, Esquire, Chairman of Darling New South Wales Committees Conelan, William Patrick, Esquire Griffith Queensland Corser, Bernard Henry, Esquire Wide Bay Queensland Daly, Frederick Michael, Esquire Martin New South Wales Davidson, Charles William, Esquire, O.B.E. Capricornia Queensland Dedman, Hon. John Johnstone .. Corio Victoria Drakeford, Hon, Arthur Samuel Maribyrnong Victoria Duthie, Gilbert William Arthur, Esquire Wilmot Tasmania Edmonds, William Frederick, Esquire Herbert ., Queensland Evatt, Rt, Hon. Herbert Vere, K.C. Barton New South Wales Fadden, Rt. Hon. Arthur William Darling Downs Queensland Falkinder, Charles William Jackson, Franklin Tasmania Esquire, D.S.O., D.F.C. Falstein, Sydney Max, Esquire . -

Inquiry Into the Regional Partnerships Program

The Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Regional Partnerships and Sustainable Regions programs October 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 0 642 71580 7 This document is prepared by the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Committee for the inquiry Senator Michael Forshaw (Chair) ALP, NSW Senator David Johnston (Deputy Chair) LP, WA (replaced Senator Mitchell Fifield) Senator Guy Barnett LP, TAS (replaced Senator John Watson) Senator Carol Brown ALP, TAS Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA Senator Kerry O'Brien ALP, TAS (replaced Senator Claire Moore) Senator Kim Carr ALP, VIC (replaced Senator George Campbell 2 December 2004 to 22 June 2005; Senator Ursula Stephens 1 July 2005 to 17 August 2005, except on 14-15 July, 18-19 July 2005) Senator Ursula Stephens ALP, NSW (replaced Senator George Campbell 22 June 2005 to 13 September 2005) Participating members Senators Abetz, Bartlett, Bishop, Boswell, Brandis, Bob Brown, Carr, Chapman, Colbeck, Conroy, Coonan, Crossin, Eggleston, Evans, Faulkner, Ferguson, Ferris, Fielding, Fierravanti-Wells, Ludwig, Lundy, Sandy Macdonald, Mason, McGauran, McLucas, Milne, Parry, Payne, Ray, Sherry, Siewert, Stephens, Trood and Webber. Secretariat Alistair Sands Committee Secretary Terry Brown Principal Research Officer Lisa Fenn Acting Principal Research Officer Melinda Noble Principal Research Officer Sophie Power Principal Research Officer (August 2005) Alex Hodgson Executive Assistant Committee address Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee SG.60 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3530 Fax: 02 6277 5809 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate_fpa iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Members of the Committee for the inquiry................................................... -

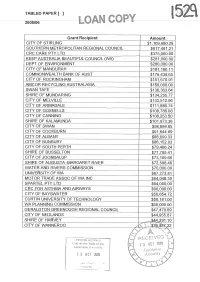

Tabled Paper [I

TABLED PAPER [I 2005/06 Grant Recipient Amount CITY OF STIRLING 1,109,680.28 SOUTHERN METROPOLITAN REGIONAL COUNCIL $617,461.21 CRC CARE PTY LTD $375,000.00 KEEP AUSTRALIA BEAUTIFUL COUNCIL (WA) $281,000.00 DEPT OF ENVIRONMENT $280,000.00 ITY OF MANDURAH $181,160.11 COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUST $176,438.65 CITY OF ROCKINGHAM $151,670.91 AMCOR RECYCLING AUSTRALASIA 50,000.00 SWAN TAFE $136,363.64 SHIRE OF MUNDARING $134,255.77 CITY OF MELVILLE $133,512.96 CITY OF ARMADALE $111,880.74 CITY OF GOSNE LS $108,786.08 CITY OF CANNING $108,253.50 SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA $101,973.36 CITY OF SWAN $98,684.85 CITY OF COCKBURN $91,644.69 CITY OF ALBANY $88,699.33 CITY OF BUNBURY $86,152.03 CITY OF SOUTH PERTH $79,466.24 SHIRE OF BUSSELTON $77,795.41 CITY OF JOONDALUP $73,109.66 SHIRE OF AUGUSTA -MARGARET RIVER $72,598.46 WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION $70,000.00 UNIVERSITY OF WA $67,272.81 MOTOR TRADE ASSOC OF WA INC $64,048.30 SPARTEL PTY LTD $64,000.00 CRC FOR ASTHMA AND AIRWAYS $60,000.00 CITY OF BAYSWATER $50,654.72 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY $50,181.00 WA PLANNING COMMISSION $50.000.00 GERALDTON GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUN $47,470.69 CITY OF NEDLANDS $44,955.87_ SHIRE OF HARVEY $44,291 10 CITY OF WANNEROO 1392527_ 22 I Il 2 Grant Recisien Amount SHIRE OF MURRAY $35,837.78 MURDOCH UNIVERSITY $35,629.83 TOWN OF KWINANA $35,475.52 PRINTING INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION $34,090.91 HOUSING INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION $33,986.00 GERALDTON-GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUNCIL $32,844.67 CITY OF FREMANTLE $32,766.43 SHIRE OF MANJIMUP $32,646.00 TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE $32,414.72 WA LOCAL GOVERNMENT -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 30 October 2002 (extract from Book 3) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Health............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education Services and Minister for Youth Affairs......... The Hon. M. M. Gould, MLC Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Energy and Resources and Minister for Ports.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Minister for State and Regional Development, Treasurer and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Workcover........... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Senior Victorians and Minister for Consumer Affairs....... The Hon. C. M. Campbell, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Environment and Conservation.......................... The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections........................................ The Hon. A. Haermeyer, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs............ The Hon. K. G. Hamilton, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Manufacturing Industry and Minister for Racing............................................ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Minister for Education and Training................................ The Hon. L. J. Kosky, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations.............. The Hon. J. J. J.