Martin Crimp's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One a Theoretical Background to the Figure of The

19 Chapter One A Theoretical Background to the figure of the Artist in Literature and Theatre In an article published in Fall 2009, Csilla Bertha maintains that the central place an artist occupies within a work of art adds an additional dimension to plays, since the fictional artist’s point of view, attitudes to the world and evaluation of phenomena, may double or multiply the layers of the connections between art and life. She then adds: If an artist is chosen to be the protagonist of a play or novel, that choice naturally leads to the thematization of questions and dilemmas about the existence of art and the artist; relations between art and life, art/artist and the world; the nature of artistic creation; differences between ways of life, values, and views of ordinary people and artists; relations between individual and community, between the subject and objective reality; and many other similar issues.1 No doubt, with the advent of highly sophisticated and challenging notions such as Formalism2 and the death of the author,3 it is hard to conceive the figure of the artist without paying attention to the interrelations between art and life in which the ideal and reality, subject and object, constitute sharp contrasts. Traditionally, this dialectical relationship forms “binary 1 Csilla Bertha, “Visual Art and Artist in Contemporary Irish Drama”, Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) v. 15, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 347. 2 Formalism is a Russian literary movement which originated in the second decade of the twentieth century. Its leading figures were both linguists and literary historians such as Boris Eikhenbaum (1886-1959), Roman Jakobson (1895-1982), Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984), Boris Tomashevskij (1890-1957) and Jurij Tynjanov (1894-1943). -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

Come up to the Lab a Sciart Special

024 on tourUK DRAMA & DANCE 2004 COME UP TO THE LAB A SCIART SPECIAL BOBBY BAKER_RANDOM DANCE_TOM SAPSFORD_CAROL BROWN_CURIOUS KIRA O’REILLY_THIRD ANGEL_BLAST THEORY_DUCKIE CHEEK BY JOWL_QUARANTINE_WEBPLAY_GREEN GINGER CIRCUS_DIARY DATES_UK FESTIVALS_COMPANY PROFILES On Tour is published bi-annually by the Performing Arts Department of the British Council. It is dedicated to bringing news and information about British drama and dance to an international audience. On Tour features articles written by leading and journalists and practitioners. Comments, questions or feedback should be sent to FEATURES [email protected] on tour 024 EditorJohn Daniel 20 ‘ALL THE WORK I DO IS UNCOMPLETED AND Assistant Editor Cathy Gomez UNFINISHED’ ART 4 Dominic Cavendish talks to Declan TheirSCI methodologies may vary wildly, but and Third Angel, whose future production, Donnellan about his latest production Performing Arts Department broadly speaking scientists and artists are Karoshi, considers the damaging effects that of Othello British Council WHAT DOES LONDON engaged in the same general pursuit: to make technology might have on human biorhythms 10 Spring Gardens SMELL LIKE? sense of the world and of our place within it. (see pages 4-7). London SW1A 2BN Louise Gray sniffs out the latest projects by Curious, In recent years, thanks, in part, to funding T +44 (0)20 7389 3010/3005 Kira O’Reilly and Third Angel Meanwhile, in the world of contemporary E [email protected] initiatives by charities like The Wellcome Trust dance, alongside Wayne McGregor, we cover www.britishcouncil.org/arts and NESTA (the National Endowment for the latest show from Carol Brown, which looks COME UP TO Science, Technology and the Arts), there’s THE LAB beyond the body to virtual reality, and Tom Drama and Dance Unit Staff 24 been a growing trend in the UK to narrow the Lyndsey Winship Sapsford, who’s exploring the effects of Director of Performing Arts THEATRE gap between arts and science professionals John Kieffer asks why UK hypnosis on his dancers (see pages 9-11). -

2008, WDA Global Summit

World Dance Alliance Global Summit 13 – 18 July 2008 Brisbane, Australia Australian Guidebook A4:Aust Guide book 3 5/6/08 17:00 Page 1 THE MARIINSKY BALLET AND HARLEQUIN DANCE FLOORS “From the Eighteenth century When we come to choosing a floor St. Petersburg and the Mariinsky for our dancers, we dare not Ballet have become synonymous compromise: we insist on with the highest standards in Harlequin Studio. Harlequin - classical ballet. Generations of our a dependable company which famous dancers have revealed the shares the high standards of the glory of Russian choreographic art Mariinsky.” to a delighted world. And this proud tradition continues into the Twenty-First century. Call us now for information & sample Harlequin Australasia Pty Ltd P.O.Box 1028, 36A Langston Place, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia Tel: +61 (02) 9869 4566 Fax: +61 (02) 9869 4547 Email: [email protected] THE WORLD DANCES ON HARLEQUIN FLOORS® SYDNEY LONDON LUXEMBOURG LOS ANGELES PHILADELPHIA FORT WORTH Ausdance Queensland and the World Dance Alliance Asia-Pacific in partnership with QUT Creative Industries, QPAC and Ausdance National and in association with the Brisbane Festival 2008 present World Dance Alliance Global Summit Dance Dialogues: Conversations across cultures, artforms and practices Brisbane 13 – 18 July 2008 A Message from the Minister On behalf of our Government I extend a warm Queensland welcome to all our local, national and international participants and guests gathered in Brisbane for the 2008 World Dance Alliance Global Summit. This is a seminal event on Queensland’s cultural calendar. Our Government acknowledges the value that dance, the most physical of the creative forms, plays in communicating humanity’s concerns. -

Book of Abstracts

ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Thursday, October 11, 2018 9.45 PANEL: Across Languages Chair: Claire Hélie (Lille University) 1. Maggie Rose (Milan University) Importing new British plays to Italy. Rethinking the role of the theatre translator Over the last three decades I have worked as a co-translator and a cultural mediator between the UK and Italy, bringing plays by Alan Bennett, Edward Bond, Caryl Churchill, Claire Dowie, David Greig, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Hanif Kureishi, Liz Lochhead, Sabrina Mahfouz, Rani Moorthy, among others,to the Italian stage. Bearing in mind a complex web of Italo-British relations, I will discuss how my strategies of cultural mediation have evolved over the years as a response to significant changes in the two theatre systems. I will explore why the task of finding a publisher and a producer\director for some British authors has been more difficult than for others, the stage and critical success of certain dramatists in Italy more limited. I will look specifically at the Italian ‘journeys’ of the following writers: Caryl Churchill and my co-translation of Top Girls (1986) and A Mouthful of Birds, Edward Bond and my co-translation of The War Plays for the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin and Alan Bennett and my co-translation of The History Boys at Teatro Elfo Pucini from 2011-3013, at Teatro Elfo Puccini and national tours. Maggie Rose teaches British Theatre Studies and Performance at the University of Milan and spends part of the year in the UK for her writing and research. She is a member of the Scottish Society of Playwrights and her plays have been performed in the UK and in Italy. -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

F-1E3-56B457b217710.Pdf

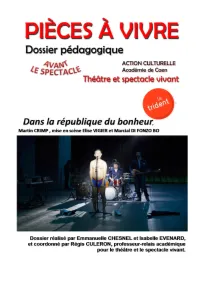

* THEATRE ET SPECTACLE VIVANT DANS LA REPUBLIQUE DU BONHEUR 2015 –SOMMAIRE– Première partie : avant la représentation I. Martin Crimp, Marcial di Fonzo Bo et Elise Vigier : la rencontre d'artistes contemporains p. 2 II. Titre, sous-titre, structure de la pièce : premières hypothèses p. 5 III. Une histoire de famille p. 7 IV. Le bonheur pour tous ? p. 9 V. Et sur scène ? p. 10 Annexes 1. Petits dialogues p. 11 2. Oncle Bob : monologue p. 12 3. Page extraite de Dans la république du bonheur p. 13 4. Les personnages parlent du bonheur p. 14 « Pièces à vivre » : une série de dossiers pédagogiques conçus en partenariat par la Délégation Académique à l’Action Culturelle de l’Académie de Caen et les structures théâtrales de l’académie à l’occasion de spectacles accueillis ou créés en Région Basse-Normandie. Le théâtre est vivant, il est créé, produit, accueilli souvent bien près des établissements scolaires ; les dossiers « Pièces à vivre », construits par des enseignants en collaboration étroite avec l’équipe de création, visent à fournir aux professeurs des ressources pour exploiter au mieux en classe un spectacle vu. Divisés en deux parties, destinées l’une à préparer le spectacle en amont, l’autre à analyser la représentation, ils proposent un ensemble de pistes que les enseignants peuvent utiliser intégralement ou partiellement. Retrouvez ce dossier, ainsi que d’autres de la même collection et des ressources pour l’enseignement du théâtre sur le site de la Délégation Académique à l’action Culturelle de l’Académie de Caen : http://www.discip.ac-caen.fr/aca/ Délégation Académique à l’Action Culturelle de Caen 1 * THEATRE ET SPECTACLE VIVANT DANS LA REPUBLIQUE DU BONHEUR 2015 I. -

The Dilemma of the Artist in Contemporary British Theatre: a Theoretical Background

Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts - Volume 2, Issue 4 – Pages 243-258 The Dilemma of the Artist in Contemporary British Theatre: A Theoretical Background By Majeed Mohammed Midhin Clare Finburgh† The present paper tackles the dilemma of the artist in contemporary British theatre. It commences by introducing a clear-cut definition of the dilemma of the artist in literature.There are certainly many dilemmas for the artist. One of the most painful is social: How can the artist function as a member of a certain community and, at the same time, retain the distinctiveness of his/her role as an outsider whose social usefulness is based on his/her chronic estrangement from the ordinary concerns of society?; by this, I mean the perplexing dilemma in which the artist finds in his/her struggle to reconcile private desire to public expectation. A second dilemma of the artist is economic: How can artists practice their art? This dilemma has two facets. On the one hand it is related to subsidy the art received from public budget. On the other, it is the materialistic norms of the society in which the artist has immersed himself/herself. Indeed, the dilemma that faces radical artists nowadays is that the popular forms of communication are often controlled by conventional and commercial forces at work in society. However, it is not only money which is the source of the artist's economic dilemma, but rather the existence or the paucity of good audiences. Under such perilous circumstances, the artist's genuine dilemma lies in confronting the Zeitgeist, the general intellectual and moral tendencies of an era, which can be evasive and intangible. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically. -

New Scottish Drama at Home and in the German-Speaking Theatre

Michael Raab (Frankfurt) No More Beautiful Losers: New Scottish Drama at Home and in the German-Speaking Theatre About the reception of new Scottish plays in London, the dramatist David Greig writes that the critics there “feel most comfortable with Scottish work when it fits their understanding of Scots – violent and funny poor people who are slightly frightening. The softer voices, the poetic voices, and the experimental voices are met with bemusement, apathy or patronising disdain”. But, surprisingly, on a 2002 list of ten playwrights thought to be “the future of British theatre” by The Guardian four were Scots. Most of their works were staged at the Traverse Theatre, Scotland’s equivalent to the Royal Court. The establishment of a non-building-based new National Theatre for Scotland further boosted an already lively scene. In a small nation of five million people 600,000 regularly go to the theatre. Joyce McMillan, critic for The Scotsman, emphasizes the importance of devolution after the successful referendum in 1997 for the development of Scottish playwriting. In her opinion it gave young authors the confidence to say, “We’re cool enough, postmodern enough and mature enough not to be spending a lot of time thinking about being Scottish.” The essay examines the enormous formal breadth of new Scottish drama from its ‘annus mirabilis’ in 2002 until today, as well as its reception in the German-speaking theatre. Describes you as a pair of ‘Celtic lyricists’, you could sue the buggers. (John Byrne: Colquhoun and MacBryde) Joyce McMillan, critic for The Scotsman, emphasizes the importance of devolution after the successful referendum in 1997 for the development of Scottish playwriting. -

Full Cast Announced for the Treatment

PRESS RELEASE Friday 24 February 2017 THE ALMEIDA THEATRE ANNOUNCES THE FULL CAST FOR THE TREATMENT, MARTIN CRIMP’S CONTEMPORARY SATIRE, DIRECTED BY LYNDSEY TURNER CHOREOGRAPHER ARTHUR PITA JOINS THE CREATIVE TEAM Joining Aisling Loftus and Matthew Needham in THE TREATMENT will be Gary Beadle, Ian Gelder, Ben Onwukwe, Julian Ovenden, Ellora Torchia, Indira Varma, and Hara Yannas. The Treatment begins previews at the Almeida Theatre on Monday 24 April and runs until Saturday 10 June. The press night is Friday 28 April. New York. A film studio. A young woman has an urgent story to tell. But here, people are products, movies are money and sex sells. And the rights to your life can be a dangerous commodity to exploit. Martin Crimp’s contemporary satire is directed by Lyndsey Turner, who returns to the Almeida following her award-winning production of Chimerica. The Treatment will be designed by Giles Cadle, with lighting by Neil Austin, composition by Rupert Cross, fight direction by Bret Yount, sound by Chris Shutt, and voice coaching by Charmian Hoare. The choreographer is Arthur Pita. Casting is by Julia Horan. ALMEIDA QUESTIONS In response to The Treatment - where it’s material that matters – Whose Life Is It Anyway? continues the Almeida’s programme of pre-show discussions as a panel delves into the worldwide fascination with constructed realities in art and in life. When you sell your story is your life still your own? In the golden age of social media - where immaculately contrived worlds are labelled as real life - what is the cost? Can truth be traced in art at all? The panel includes Instagram star Deliciously Stella, Made In Chelsea producer Nick Arnold, and Anita Biressi, Professor of Media and Communications at Roehampton University. -

History in the Age of Fracture

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 The Politics of Time in Recent English History Plays Jay M. Gipson-King Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVSERITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE, AND DANCE HISTORY IN THE AGE OF FRACTURE: THE POLITICS OF TIME IN RECENT ENGLISH HISTORY PLAYS By JAY M. GIPSON-KING A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester: 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Jay M. Gipson-King defended on October 27, 2010. Mary Karen Dahl Professor Directing Dissertation James O‘Rourke University Representative Natalya Baldyga Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to the vast number of people who made this dissertation possible. First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee chair, Mary Karen Dahl, for her guidance throughout this project and my graduate career; it is due to her that I developed my love of contemporary British theatre in the first place. I also thank committee member Natalya Baldyga, for sharing her love of the Futurists; University Representative James O‘Rourke, for his insightful reading of the manuscript and his outside perspective; former committee member Caroline Joan S. (―Kay‖) Picart, whose early feedback helped shape the structure the prospectus; and former committee member Amit Rai, who introduced me to affect theory.