Women and Children First: the Complexity of Societal Change in Dracula and NOS4A2 by Sarah White Honors Thesis Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bingo Board Hint Sheet

Hint/URL sheet South Carolina Books Visit any Berkeley County Library Branch. In the collection, there are books that have a yellow circle sticker on the spine label. Those stickers designate the book as a South Carolina Book. URLs Berkeley County Library System homepage https://berkeleylibrarysc.org/ Mobile Library Link https://berkeleylibrarysc.org/bookmobile-stops/ Berkeley County Library System Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/BerkeleyLibrarySC Berkeley County Library System Twitter https://twitter.com/bcls Berkeley County Library System Instagram https://www.instagram.com/berklibsc/ Good Reads https://www.goodreads.com/ Fantastic Fiction https://www.fantasticfiction.com/ Help with Book Genres for the BINGO BOARDS (This is just a sampling) Cozy Mysteries A Spell for Trouble – Esme Addison Booked for Death – Victoria Gilbert Elementary, She Read – Vicki Delany Twelve Slays of Christmas – Jacqueline Frost Death by Darjeeling – Laura Childs Books Made into TV/Movies The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring – JRR Tolkien American Gods – Neil Gaiman Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Blade Runner) – Philip K. Dick Everything, Everything – Nicola Yoon Girl, Interrupted – Susanna Kaysen Horror Authors other than Stephen King Shirley Jackson Darcy Coates Paul Tremblay Stephen Graham Jones Tananarive Due Independent Authors Deanne Rupert Cameron Jace R.F. Hurteau Warren Esby Tay Mo’nae Short Stories Scorched: A collection of short stories on survivors – Irit Amiel The (Other) You – Joyce Carol Oates What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours – Helen Oyeyemi We Are Where the Nightmares Go - C. Robert Cargill Full Throttle – Joe Hill Poetry I Would Leave Me If I Could – Halsey Moods of the Sea – George C. -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY Veronika Glaserová The Importance and Meaning of the Character of the Writer in Stephen King’s Works Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2014 Olomouc 2014 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem předepsaným způsobem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne Podpis: Poděkování Děkuji vedoucímu práce za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 1. Genres of Stephen King’s Works ................................................................................. 8 1.1. Fiction .................................................................................................................... 8 1.1.1. Mainstream fiction ........................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Horror fiction ................................................................................................. 10 1.1.3. Science fiction ............................................................................................... 12 1.1.4. Fantasy ........................................................................................................... 14 1.1.5. Crime fiction ................................................................................................. -

Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" by Joe Hill, Stephen King, Richard Matheson for Online Ebook

Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" Joe Hill, Stephen King, Richard Matheson Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" Joe Hill, Stephen King, Richard Matheson Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" Joe Hill, Stephen King, Richard Matheson Road Rage unites Richard Matheson's classic Duel and the contemporary work it inspired—two power- packed short stories by three of the genre's most acclaimed authors. Duel, an unforgettable tale about a driver menaced by a semi truck, was the source for Stephen Spielberg's acclaimed first film of the same name. Throttle, by Stephen King and Joe Hill, is a duel of a different kind, pitting a faceless trucker against a tribe of motorcycle outlaws, in the simmering Nevada desert. Their battle is fought out on twenty miles of the most lonely road in the country, a place where the only thing worse than not knowing what you're up against, is slowing down . Download Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" ...pdf Read Online Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Road Rage CD: Includes 'Duel" and "Throttle" Joe Hill, Stephen King, Richard Matheson From reader reviews: Alex Lynch: Do you have favorite book? In case you have, what is your favorite's book? Publication is very important thing for us to know everything in the world. Each e-book has different aim or maybe goal; it means that guide has different type. Some people sense enjoy to spend their time for you to read a book. -

2021 Independent Bookstore Day Catalog of Exclusives

2021 Independent Bookstore Day Catalog of Exclusives Independent Bookstore Day is online and in-store Saturday, April 24, 2021 Order deadline is Friday, February 5, 2021 (we cannot accept late orders!) Table of Contents New Guidelines (Please Read Carefully!) Pg. 3 Our Sponsors Pg. 4 ADULT TITLES Exclusive Signed Edition of Sharks in the Time of Saviors Pg. 5 “Little Victories” Pouch Pg. 6 Exclusive Signed Edition of Hummingbird Salamander Pg. 7 Exclusive Signed Edition of Cook, Eat, Repeat Pg. 8 “Bad Citizen” Graffiti Stencil Pg. 9 Embodied: An Intersectional Feminist Comics Poetry Anthology Pg. 10 IBD Exclusive Edition of In the Tall Grass Pg. 11 $7 Story: Being Alive is a Good Idea Pg. 12 Independent Bookstores of the U.S. Map Pg. 13 Exclusive Independent Bookstore Day Blackwing Pencils Pg. 14 TITLES FOR CHILDREN & YOUNG PEOPLE The ABCs of Black History Print Pg. 16 Baby Yoda Onesie Pg. 17 FREE STUFF I Can Read! Comics / Macmillan’s Best Parties in Literature Pg. 18 Broken, An Oracle Card Deck by Jenny Lawson Pg. 19 Outside, Inside Independent Bookstore Day Lawn Signs Pg. 20 “I Visited An Independent Bookstore Today” Stickers Pg. 21 The Black Friend IBD Bumper Stickers Pg. 22 Milo Imagines the World Event Kit Pg. 23 Special Terms & Promotions Pg. 24 Free IBD Bookmarks Pg. 25 2021 IBD Totes & Shirts Pg. 26 NEW GUIDELINES FOR 2021 PLEASE READ CAREFULLY 1. All current dues-paying members of the ABA and a local regional independent booksellers association are eligible to participate in IBD. Membership in both is required because IBD is supported financially by ABA and the 8 regional bookseller associations. -

Stephen King the Stephen King the Stephen King Checklist Checklist Checklist the Dark Tower the Stand the Dark Tower the Stand the Dark Tower the Stand 1

The Stephen King The Stephen King The Stephen King Checklist Checklist Checklist The Dark Tower The Stand The Dark Tower The Stand The Dark Tower The Stand 1. The Gunslinger The Dead Zone 1. The Gunslinger The Dead Zone 1. The Gunslinger The Dead Zone 2. The Drawing of the Firestarter 2. The Drawing of the Firestarter 2. The Drawing of the Firestarter Three The Mist Three The Mist Three The Mist 3. The Waste Lands Cujo 3. The Waste Lands Cujo 3. The Waste Lands Cujo 4. Wizard and Glass Pet Sematary 4. Wizard and Glass Pet Sematary 4. Wizard and Glass Pet Sematary 5. Wolves of the Calla Christine 5. Wolves of the Calla Christine 5. Wolves of the Calla Christine 6. Song of Susannah Cycle of the Werewolf 6. Song of Susannah Cycle of the Werewolf 6. Song of Susannah Cycle of the Werewolf 7. The Dark Tower It 7. The Dark Tower It 7. The Dark Tower It 8. The Wind Through the The Eyes of the Dragon 8. The Wind Through the The Eyes of the Dragon 8. The Wind Through the The Eyes of the Dragon Keyhole The Tommyknockers Keyhole The Tommyknockers Keyhole The Tommyknockers Misery Misery Misery Talisman The Dark Half Talisman The Dark Half Talisman The Dark Half (with Peter Straub) Needful Things (with Peter Straub) Needful Things (with Peter Straub) Needful Things 1. The Talisman Dolores Claiborne 1. The Talisman Dolores Claiborne 1. The Talisman Dolores Claiborne 2. Black House Gerald's Game 2. Black House Gerald's Game 2. Black House Gerald's Game Insomnia Insomnia Insomnia The Green Mile Rose Madder The Green Mile Rose Madder The Green Mile Rose Madder 1. -

An Interview with Stephen King by John C. Tibbetts

“We Walk Your Dog at Night!”: An Interview with Stephen King by John C. Tibbetts Stephen King is a phenomenon. He is without question the most popular writer of horror fiction of all time. In l973 he was living with his family in a trailor in Hampden, Maine, struggling to make a living as a high school teacher, when he published his first novel, Carrie, a tale of a girl with telekinetic powers. Its sales in hardcover were modest (l3,000) but enough to inspire a paperback reprint and a popular film adaption by Brian De Palma in l976. His “breakthrough” book, Salem's Lot, came out that year and quickly sold 3,000,000 copies. Within the next four years The Shining, The Stand, Night Shift, and The Dead Zone—all best-selling horror fiction—established King as the reigning Master of the Macabre. When he co- authored The Talisman in l984 with Peter Straub [See the Straub interview elsewhere in these pages], it was a publishing event unparalleled in modern times. Today over l00 million copies of his books are in print. King's work is frankly derivative of the traditions of l9th century gothic horror. Carrie is written in the style of the "epistolary" novel of the late l8th century. Salem's Lot is an update on Bram Stoker's vampire novel, Dracula. Christine is a variant on Oscar Wilde's The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Pet Sematary is a retelling of W. W. Jacobs' "The Monkey's Paw." And The Dark Half draws from the rich vein of "doppelganger" stories by Poe, Hoffmann, and Stevenson. -

Joe Hill’S Horns

Book Review: Joe Hill’s Horns Even if you’re not a fan of horror, you’ve heard of Stephen King. It’s hard not to, as he has written more books than most any other three authors put together, and currently sits atop his own publishing house, scribbling away on napkins that somehow morph into bestsellers every few months. But this is about the son of the King, Joe Hill. You might know that name because the TV show “NOS4A2,” based on his book, has been filming here recently. He writes under a psuedonym to avoid cashing in on his father’s success, but that’s hard to do when your dad can point to a piece of paper and turn it into money. I didn’t read NOS4A2 because I don’t have an interest in the sudden swell of vampire fandom, since I’ve been burned before. I did, however, pick up a copy of one of Hill’s earlier entries into the horror genre, Horns, and it is so much fun that Hill made me a fan. The book begins with a simple premise — you know the story — boy meets girl, they fall in love, girl is brutally murdered, they blame boy and boy’s life spirals downward into self-loathing, drinking and despair. Then one day boy wakes up with a pair of horns growing from his head, and everyone around him seems compelled to speak their deepest, darkest secrets to him like they’re having a casual conversation. This leads to the revelation of who killed said girl in the first place, making this book a supernatural horror murder mystery romance. -

Stephen King

Stephen King From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For other people named Stephen King, see Stephen King (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2010) Stephen King Stephen King, February 2007 Stephen Edwin King Born September 21, 1947 (age 63) Portland, Maine, United States Pen name Richard Bachman, John Swithen Novelist, short story writer, screenwriter, Occupation columnist, actor, television producer, film director Horror, fantasy, science fiction, drama, gothic, Genres genre fiction, dark fantasy Spouse(s) Tabitha King Naomi King Children Joe King Owen King Influences[show] Influenced[show] Signature stephenking.com Stephen Edwin King (born September 21, 1947) is an American author of contemporary horror, suspense, science fiction and fantasy fiction. His books have sold more than 350 million copies[7] and have been made into many movies. He is most known for the novels Carrie, The Shining, The Stand, It, Misery, and the seven-novel series The Dark Tower, which King wrote over a period of 27 years. As of 2010, King has written and published 49 novels, including seven under the pen name Richard Bachman, five non-fiction books, and nine collections of short stories including Night Shift, Skeleton Crew, and Everything's Eventual. Many of his stories are set in his homestate of Maine. He has collaborated with authors Peter Straub and Stewart O'Nan. The novels The Stand, The Talisman, and The Dark Tower series have also been made into comic books, along with the short story N. -

The Psychopath in the Stephen King's Misery A

THE PSYCHOPATH IN THE STEPHEN KING’S MISERY A THESIS BY ROSA FELESIA DEBORA TARIGAN REG. NO. 120705026 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, ROSA FELESIA DEBORA TARIGAN, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS CONTAINS NO MATERIAL PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE OR EXTRACTED IN WHOLE OR IN PART FROM A THESIS BY WHICH I HAVE QUALIFIED FOR OR A WARDED ANOTHER DEGREE. NO OTHER PERSON’S WORK HAS BEEN USED WITHOUT DUE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IN THE MAIN TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS HAS NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF ANOTHER DEGREE IN ANY TERTIARY EDUCATION. Signed : Date : July 20, 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION NAME : ROSA FELSIA DEBORA TARIGAN TITLE OF THESIS : THE PSYCHOPATH IN THE STEPHEN KING’S MISERY QUALIFICATION : S-1/SARJANA SASTRA DEPARTMENT : ENGLISH I AM WILLING THAT MY THESIS SHOULD BE AVAILABLE FOR REPRODUCTION AT THE DISCRETION OF THE LIBRARIAN OF DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA ON THE UNDERSTANDING THAT USERS ARE MADE AWARE OF THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA. Signed : Date : July 20, 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ACKNOWLEDGMENT Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude to the Almighty, Jesus Christ, mankind’s savior who loves me with His unconditional affection, holds my hand in every situations and blesses me with a great life that I can pass all problems in my life without changing and remove my faith in Him. -

Horror Authors

If you like If you like If you like Horror Horror Horror Novels Novels Novels try these try these try these authors! authors! authors! Neil Gaiman Neil Gaiman Neil Gaiman Joe Hill Joe Hill Joe Hill Shirley Jackson Shirley Jackson Shirley Jackson Stephen King Stephen King Stephen King Dean R. Koontz Dean R. Koontz Dean R. Koontz Chuck Palahniuk Chuck Palahniuk Chuck Palahniuk Tom Piccirilli Tom Piccirilli Tom Piccirilli Edgar Allen Poe Edgar Allen Poe Edgar Allen Poe Anne Rice Anne Rice Anne Rice John Saul John Saul John Saul Dan Simmons Dan Simmons Dan Simmons Peter Straub Peter Straub Peter Straub Note: Some of these authors also Note: Some of these authors also Note: Some of these authors also write in genres other than horror. write in genres other than horror. write in genres other than horror. For more great For more great For more great reading recommen- reading recommen- reading recommen- dations check out dations check out dations check out NoveList. We can NoveList. We can NoveList. We can show you how to show you how to show you how to use it to find books use it to find books use it to find books similar to ones you similar to ones you similar to ones you like to read. like to read. like to read. http:/tewksburylibrary.virtualtownhall.net/ http:/tewksburylibrary.virtualtownhall.net/ http:/tewksburylibrary.virtualtownhall.net/ pages/TewksburyLibrary_Research online#books pages/TewksburyLibrary_Research online#books pages/TewksburyLibrary_Research online#books ~~Annotations courtesy of NoveList~~ ~~Annotations courtesy of NoveList~~ ~~Annotations courtesy of NoveList~~ 300 Chandler Street 300 Chandler Street 300 Chandler Street Tewksbury, MA 01876 Tewksbury, MA 01876 Tewksbury, MA 01876 978-640-4490 978-640-4490 978-640-4490 www.tewksburypl.org www.tewksburypl.org www.tewksburypl.org . -

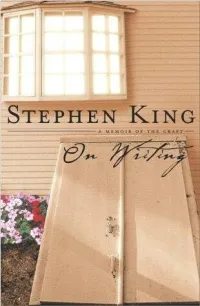

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers.