Construction, Reformation, and the Rule Against Perpetuities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2014 Melanie Leslie – Trusts and Estates – Attack Outline 1

Spring 2014 Melanie Leslie – Trusts and Estates – Attack Outline Order of Operations (Will) • Problems with the will itself o Facts showing improper execution (signature, witnesses, statements, affidavits, etc.), other will challenges (Question call here is whether will should be admitted to probate) . Look out for disinherited people who have standing under the intestacy statute!! . Consider mechanisms to avoid will challenges (no contest, etc.) o Will challenges (AFTER you deal with problems in execution) . Capacity/undue influence/fraud o Attempts to reference external/unexecuted documents . Incorporation by reference . Facts of independent significance • Spot: Property/devise identified by a generic name – “all real property,” “all my stocks,” etc. • Problems with specific devises in the will o Ademption (no longer in estate) . Spot: Words of survivorship . Identity theory vs. UPC o Abatement (estate has insufficient assets) . Residuary general specific . Spot: Language opting out of the common law rule o Lapse . First! Is the devisee protected by the anti-lapse statute!?! . Opted out? Spot: Words of survivorship, etc. UPC vs. CL . If devise lapses (or doesn’t), careful about who it goes to • If saved, only one state goes to people in will of devisee, all others go to descendants • Careful if it is a class gift! Does not go to residuary unless whole class lapses • Other issues o Revocation – Express or implied? o Taxes – CL is pro rata, look for opt out, especially for big ticket things o Executor – Careful! Look out for undue -

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised Or Amended in 2005)

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised or Amended in 2005) drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-THIRTEENTH YEAR PORTLAND, OREGON JULY 30-AUGUST 6, 2004 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright ©2004 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS April 2005 ABOUT NCCUSL The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 114th year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. Conference members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • NCCUSL strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • NCCUSL statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • NCCUSL keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • NCCUSL’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

Deed Recording

DEED RECORDING Deeds are important legal documents. The Onondaga County Clerk’s Office strongly recommends consulting an attorney regarding the preparation and filing/recording of any legal document. OUR OFFICE IS PROHIBITED BY LAW FROM PROVIDING ANY LEGAL ADVCE. THE ACCEPTANCE OF AN INSTRUMENT FOR RECORDING IN NO WAY IMPLIES AN ENDORSEMENT OR LEGAL SUFFICIENCY OR A GUARANTEE OF TITLE. IF YOU CHOOSE TO ACT AS YOUR OWN ATTORNEY YOU ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL COMPLIANCE AND ANY IMPLICATIONS THEREOF. To find a local attorney who specializes in real estate, contact the Onondaga County Bar Association Lawyer Referral Serve at 315.471.2690. Their website is located at https://www.onbar.org/ Our office does not supply forms. To purchase a New York State specific deed form, you may visit the Blumberg Legal Forms website at: https://www.blumberg.com/forms/ All deed filings must be accompanied by both an RP-5217 and TP 584 All recording in Onondaga County require a legal description for the subject property. ADDITIONAL RECORDING FEE EFFECTIVE MARCH 11, 2020 Effective March 11, 2020 there will be a $10 fee added to all residential deed recordings. On January 11, 2020 Governor Cuomo signed into law an amendment to Real Property Law Section 291 that requires County Clerks to notify the owner(s) of record of residential real property when a document is recorded affecting said residential property. The law also allows a reasonable fee to be assessed for said notices. The NYS Association of County Clerks, in order to provide uniformity throughout NYS, has determined that $10 is a reasonable fee per document. -

Morris & Leach: the Rule Against Perpetuities

Michigan Law Review Volume 55 Issue 1 1956 Morris & Leach: The Rule Against Perpetuities William F. Fratcher University of Missouri Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation William F. Fratcher, Morris & Leach: The Rule Against Perpetuities, 55 MICH. L. REV. 149 (1956). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol55/iss1/17 This Book Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1956] RECENT BOOKS 149 RECENT BOOKS THE RuLE AGAINST PERPETUITIES. By]. H. C. Morris and W. Barton Leach. London: Stevens & Sons. 1956. Pp. xlviii, 336. $8.90. It is more than seventy years since the publication of a book on the Rule Against Perpetuities intended for the use of lawyers of the British Commonwealth. That period has seen John Chipman Gray's definitive ex position of the Rule, basic statutory changes in the English law of property, and a vast accumulation of precedent by the courts of the Commonwealth and the United States. The publication of such a book by a competent English scholar and a leading American authority is an event of major importance. The preface states that the book, in its present form, was written by Dr. -

Title Matters Affecting Parties in Possession: By

TITLE MATTERS AFFECTING PARTIES IN POSSESSION: ADVERSE POSSESSION, AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE, & THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES BY DONALD G. SINEX SCOTT C. PETRY SUSAN A. STANTON TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 I. ADVERSE POSSESSION…….……………………………………………………………. 1 1. Adverse Possession………...………………...……………………………………….......... 2 2. Identifying Issues in Record Title…………………………………………………………. 3 a. Historical Changes in Metes and Bounds…………………………………………… 4 b. Adverse Possession of Minerals……………………………………………………… 4 c. Adverse Possession in Cotenancy, Landlord-Tenant, & Grantor-Grantee Situations………………………………………………………………………….…...... 5 d. Distinguishing Coholders from Cotenants………………………………………….. 6 3. Adverse Possession Requirement………………………………………………………… 7 4. Other Issues………………………………………...……………………………………….. 9 II. AFTER ACQUIRED TITLE………………………….…………………………………………. 10 1. The Doctrine………………..……... ……………………………………………………….. 10 2. Bases Used by Courts in Applying the Doctrine…………………………………........... 11 3. Conveyance Instruments that an Examiner is Likely to Encounter…………………… 12 a. Deeds of Trust and Liens……………………………………………………………... 12 b. Oil & Gas Leases and Limitations……………………………………………………. 14 c. Public Lands……………………………………………………………………………. 15 d. Title Acquired in Trust………………………………………………………………… 16 e. Quitclaims and Limitations…………………………………………………………… 16 4. Effect on Notice and Purchasers………………………………………………………….. 18 a. Subsequent Purchaser…………………………………………………………………. 19 b. Protections……………………………………...………………………………………. 19 c. Duty to Search…………………………………………………………………………. -

July 2007 Real Property Question 6

July 2007 Real Property Question 6 MEE Question 6 Owen owned vacant land (Whiteacre) in State B located 500 yards from a lake and bordered by vacant land owned by others. Owen, who lived 50 miles from Whiteacre, used Whiteacre for cutting firewood and for parking his car when he used the lake. Twenty years ago, Owen delivered to Abe a deed that read in its entirety: Owen hereby conveys to the grantee by a general warranty deed that parcel of vacant land in State B known as Whiteacre. Owen signed the deed immediately below the quoted language and his signature was notarized. The deed was never recorded. For the next eleven years, Abe seasonally planted vegetables on Whiteacre, cut timber on it, parked vehicles there when he and his family used the nearby lake for recreation, and gave permission to friends to park their cars and recreational vehicles there. He also paid the real property taxes due on the land, although the tax bills were actually sent to Owen because title had not been registered in Abe’s name on the assessor’s books. Abe did not build any structure on Whiteacre, fence it, or post no-trespassing signs. Nine years ago, Abe moved to State C. Since that time, he has neither used Whiteacre nor given others permission to use Whiteacre, and to all outward appearances the land has appeared unoccupied. Last year, Owen died intestate leaving his daughter, Doris, as his sole heir. After Owen’s death, Doris conveyed Whiteacre by a valid deed to Buyer, who paid fair market value for Whiteacre. -

Administration of a Deceased Wife's Interest in Community Assets Jerry A

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 4 | Number 1 Article 4 1-1-1963 Administration of a Deceased Wife's Interest in Community Assets Jerry A. Kasner Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry A. Kasner, Administration of a Deceased Wife's Interest in Community Assets, 4 Santa Clara Lawyer 30 (1963). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADMINISTRATION OF A DECEASED WIFE'S INTEREST IN COMMUNITY ASSETS Jerry A. Kasner* Modern estate planning practice, emphasizing a minimization of death taxes and probate costs, often discourages the traditional legacy of property by one spouse to the other. Property so passing may be subjected to probate and taxation twice within a short period of time.' To prevent this, a surviving spouse may be given only a limited life interest, if any at all, in the estate of the deceased spouse, with the bulk of the beneficial interest passing to succeeding genera- tions.2 Often the use of the trust device to carry out such a plan results in the selection of independent trustees and executors to achieve certain tax advantages and to provide continuity in the ad- ministration of estate assets. This form of planning for the "splitting" of interest between husband and wife necessarily results in division of the community property upon the death of either. -

Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard

SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA Information Technology Resource Management Standard VIRGINIA REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING STANDARD Virginia Information Technologies Agency (VITA) i Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PUBLICATION VERSION CONTROL ITRM Publication Version Control: It is the user's responsibility to ensure they have the latest version of the ITRM publication. Questions should be directed to the Associate Director Manager for Policy, Practice and Enterprise Architecture (PPA) (EA) at VITA’s Relationship Management Governance (RMG) Strategic Management Services (SMS). SMS EA will issue a Change Notice Alert, post it on the VITA Web site, and provide an email announcement to the Circuit Court Clerks, as well as other parties PPA EA considers to be interested in the change. This chart contains a history of this ITRM publication’s revisions. Version Date Purpose of Revision Original 05/01/2007 Base Document This administrative update is necessitated by changes in the Code of 00.1 12/08/2017 Virginia and organizational changes in VITA. No substantive changes were made to this document. ii Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PREFACE real estate settlement process for the benefit of citizens of the Commonwealth and users of the electronic Publication Designation filing system. SEC505-00.1 Sections 55-66.3 through 55-66.5 and 55-66.8 through Subject 55-66.15: This Standard for the electronic acceptance and recordation for the release of mortgage, rescinding Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard erroneously recorded certificates of satisfaction, requirements on secured creditors, and the form and Effective Date effect of satisfaction facilitates real estate transactions May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 in the Commonwealth. -

Usufruct Study Guide

Article 562 ± 578 1. Define usufruct. Usufruct is a real right by virtue of which a person is given the right to enjoy the property of another with the obligation of preserving its form and substance, unless the title constituting it or the law provides otherwise. 2. What are the three fundamental Rights Appertaining to Ownership? Ownership consists of three fundamental rights, to wit: - jus disponende (right to dispose) - jus utendi (right to use) - jus fruendi (right to the fruits) 3. Of the above-mentioned fundamental rights, what consists usufruct and naked ownership? The combination of the jus utendi and jus fruendi is called usufruct. The remaining right jus disponendi is really the essence of what is termed ³naked ownership´. 4. What right is transferred to the usufructuary and what right is remained with the owner? In a usufruct, only the jus utendi and jus fruendi over the property is transferred to the usufructuary. The owner of the property maintains the jus disponendi or the power to alienate, encumber, transform, and even destroy the same. (Hemedes vs. CA, 316 SCRA 347 1999). 5. What are the formulae with respect to full ownership, usufruct, and naked ownership? The following are the formulae: - Full Ownership equals Naked Ownership plus Usufruct - Naked Ownership equals Full Ownership minus Usufruct - Usufruct equals Full Ownership minus Naked Ownership 6. What are the characteristics or elements of usufruct? The following are the characteristics or elements of usufruct: ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS: those without which it can not be termed usufruct: (a) It is REAL RIGHT (whether registered in the Registry of Property or not). -

Jean Willey Trust

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE In the Matter of: ) C.A. No. 5935-VCG JEAN I. WILLEY TRUST ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Submitted: July 22, 2011 Decided: August 4, 2011 William W. Erhart, Esquire, of WILLIAM W. ERHART , P.A., Wilmington, Delaware, Attorney for Petitioner, Scott Willey, Mark Willey and Deborah Willey, pro se , of 2311 Shaws Corner Road, Clayton, Delaware 19938, Respondents GLASSCOCK, Vice Chancellor. This is an action for approval of accounting and termination of a testamentary trust. Jean I. Willey (“Jean”), the testator, had four sons: Todd C. Willey (“Todd”), Mark E. Willey (“Mark”), Scott B. Willey (“Scott”), and Dale S. Willey (“Dale”). 1 In her will (“Jean’s Will”), executed on November 2, 2000, Jean devised $30,000.00 to Mark in a supplemental needs trust (“Mark’s Trust”), with the remainder of her estate to be divided equally among her four sons. Todd was named as the Trustee of Mark’s Trust in Jean’s Will; Dale was named the executor of the Will. Jean passed away on September 7, 2004. Although the testimony indicates that her estate was closed in May 2005, $30,000.00 in assets was placed in Mark’s Trust on May 17, 2005, and the remainder of Jean’s estate was then distributed equally to the four Willey brothers in September 2005. In April 2009, the Willey brothers sold Jean’s real property and the proceeds were distributed equally. Todd, the petitioner in this action, filed a motion on October 28, 2010 seeking approval of the trust accounting and the termination of Mark’s Trust, the corpus of which—according to Todd—is reduced to around $5,000 and should be turned over to Mark (via his guardians). -

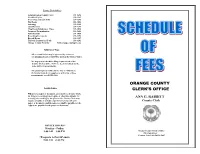

Schedule of Fees (PDF)

County Clerk Offices Administration/County Clerk 291-2690 Certified Copies 291-3287 Court Papers/Court Calls 291-3286 File Room 291-3086 Indexing 291-3285 Land Records 291-3287 Map Room/Subdivision Maps 291-3084 Passports/Naturalization 291-2698 Pistol Permits 291-3060 Recording Documents 291-3292 Record Room 291-3287 Uniform Commercial Code 291-3292 Orange County Web Site www.orangecountygov.com Subdivision Maps After a subdivision map is approved by a town or city planning board, it MUST be filed in the Clerk’s Office. We urge you to check the filing requirements of the County Clerk’s Office that have been mandated by the state and local governments. The planning board office in the city or town where the land is located can supply you with a list of these requirements, or call 291-3084. ORANGE COUNTY Legible Copies CLERK’S OFFICE Whenever a paper or document, presented to a County Clerk for filing or recording is not legible or otherwise suitable for ANN G. RABBITT scanning or recording by the process, the County Clerk may require a legible or suitable copy thereof along with such County Clerk paper or document, and the same fees shall be payable for the copy as are payable for the paper or document. OFFICE HOURS * Monday – Friday 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM Orange County Clerk’s Office 255 Main Street Goshen, New York 10924-1697 *Passports & Pistol Permits 9:00 AM – 4:30 PM ASSIGNMENT OF MORTGAGE*, To Record 45.00 MECHANICS LIEN, To File 15.00 Plus Per Page 5.00 Affidavit of Service (35 Days) 5.00 Plus Each Additional Mortgage 3.00 Discharge by Payment into Court 3.00 1st Asst. -

Recording Deeds in Lake County

Recording Deeds in Lake County Deeds for properties located in Lake County should be recorded in the Lake County Recorder of Deeds Office. Deeds are accepted for recording in person or by mail. Once recorded, the document will be assigned a document number, scanned, and entered into a Grantor/Grantee index. The original document will be returned to the party named on the document. After recording, land records are available for public viewing. As always, it is suggested that you consult legal & accounting professionals to fully understand the legal & tax implications of recording any property deed changes. If there is anything that our staff can do to help make this process easier for you, please let us know. 18 N County St – 6th Floor Waukegan, IL 60085-4358 Phone: (847) 377-2575 Fax: (847) 984-5860 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakecountyil.gov/recorder Recording Requirements: 1. Deeds must be dated, signed & notarized. 2. Parties involved must be named. 3. Grantee's (buyer) address must be listed. 4. Deeds require a complete legal description. 5. Metes & bounds legal descriptions require a Plat Act affidavit. 6. Deeds require the name & address of the Preparer. 7. Deeds require “Mail to” information (name & address) - this is where the recorded document must be returned, after it has been recorded. 8. Taxpayer name & address for tax bills must be listed. 9. All deeds require either a completed Illinois PTAX- 203 form or a signed & dated exemption statement. 10. Local municipal transfer tax stamps must be obtained at the local municipality prior to being submitted to the Recorder of Deeds Office.