Chawls: Analysis of a Middle Class Housing Type in Mumbai, India Priyanka N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Horizon Tours

New Horizon Tours Presents INTOXICATING, INCREDIBLE INDIA MARCH 14 -MARCH 26, 2020 (LAX) Mar. 14, SAT: PARTICIPANTS from Los Angeles (LAX) board on Emirates air at 4.35PM Mar. 15, SUN: LAX PARTICIPANTS ARRIVE IN DUBAI AND CONNECT FLIGHT TO MUMBAI / Washington (IAD) participants depart at 11.10 AM Mar. 16, MON: ARRIVE MUMBAI Different times- LAX passengers arrive at 2.15AM (immediate occupancy of rooms- rooms reserved from Mar. 15). IAD passengers arrive at 2.00 PM- separate arrival transfers for each in Mumbai. Arrive in Mumbai, a cluster of seven islands derives its name from Mumba devi, the patron goddess of Koli fisher folk, the oldest habitants. Meeting assistance and transfer to Hotel. Rest of the day is free. Evening welcome dinner at roof top restaurant at Hotel near airport. HOTEL.OBEROI TRIDENT (Breakfast & Dinner for LAX passengers, Dinner only for IAD participants). Mar. 17, TUE: MUMBAI - CITY TOUR – BL Breakfast at Hotel. This morning embark on city tour of Mumbai visiting the British built Gateway of India, Bombay's landmark constructed in 1927 to commemorate Emperor George V's visit, the first State, ever to see India by a reigning monarch. Followed by a drive through the city to see the unique architecture, Mumbai University, Victoria Terminus, Marine Drive, Chowpatty Beach. Next stop at Hanging Gardens (now known as Sir K.P. Mehta Gardens), where the old English art of topiary is practiced. Continue to the Dhobi Ghat, an open-air laundry where washmen physically clean and iron hundreds of items of clothing, delivering them the next day. -

Mumbai Residential June 2019 Marketbeats

MUMBAI RESIDENTIAL JUNE 2019 MARKETBEATS 2.5% 62% 27% GROWTH IN UNIT SHARE OF MID SHARE OF THANE SUB_MARKET L A U N C H E S (Q- o - Q) SEGMENT IN Q2 2019 IN LAUNCHES (Q2 2019) HIGHLIGHTS RENTAL VALUES AS OF Q2 2019* Average Quoted Rent QoQ YoY Short term Submarket New launches see marginal increase (INR/Month) Change (%) Change (%) outlook New unit launches have now grown for the third consecutive quarter, with 15,994 units High-end segment launched in Q2 2019, marking a 2.5% q-o-q increase. Thane and the Extended Eastern South 60,000 – 700,000 0% 0% South Central 60,000 - 550,000 0% 0% and Western Suburbs submarkets were the biggest contributors, accounting for around Eastern 25,000 – 400,000 0% 0% Suburbs 58% share in the overall launches. Eastern Suburbs also accounted for a notable 17% Western 50,000 – 800,000 0% 0% share of total quarterly launches. Prominent developers active during the quarter with new Suburbs-Prime Mid segment project launches included Poddar Housing, Kalpataru Group, Siddha Group and Runwal Eastern 18,000 – 70,000 0% 0% Suburbs Developers. Going forward, we expect the suburban and peripheral locations to account for Western 20,000 – 80,000 0% 0% a major share of new launch activity in the near future. Suburbs Thane 14,000 – 28,000 0% 0% Mid segment dominates new launches Navi Mumbai 10,000 – 50,000 0% 0% The mid segment continues to be the focus with a 62% share of the total unit launches during the quarter; translating to a q-o-q rise of 15% in absolute terms. -

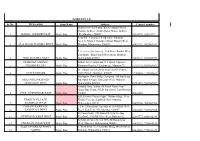

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

NOBLE PLUS Sr No

NOBLE PLUS Sr No. Br Location Shop Name Address Contact number Indian Oil Petrol Pump, Below Airport Metro Station, Andheri - Kurla Road, Marol, Andheri 1 MAROL, ANDHERI EAST Noble Plus (E), Mumbai - 400059 28349999, 28391199 Shop No. 1, Joanna Co-Operative Housing Society, Manuel Gonsalves Road, Bandra West, 2 M. G. ROAD, BANDRA WEST Noble Plus Mumbai, Maharashtra 400050 26431129, 9029069559 7-A, Seven Star Society, 33rd Road, Bandra West, Landmark : Mini Punjab Restaurant, Mumbai, 4 33RD, BANDRA WEST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400050 26493333, 9029069590 DIAMOND GARDEN, Bahari Auto Compound, S.T. Road, Opposite 5 CHEMBUR EAST Noble Plus Diamond Garden, Chembur (E), Mumbai-71 25202520, 9029069565 #6 , Maker Arcade ,Near World Trade Center, 6 CUFFE PARADE Noble Plus Cuffe Parade, Mumbai, 400005 22168888, 7718806670 Rustomjee Ozone Bldg, Goregaon - Mulund Link MULUND LINK ROAD, Rd, Sunder Nagar, Goregaon West, Mumbai, 7 GOREGAON WEST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400064 28710057, 9029069567 Ground Floor, Indian Oil Petrol Pump, Opp. Majas Bus Depot, JVLR Jogeshwari East Mumbai 8 JVLR, JOGESHWARI EAST Noble Plus 400060 28268888 #55, Krishna Vasant Sagar, Thakur village, Near THAKUR VILLAGE, Thakur Cinema, Kandivali East, Mumbai, 9 KANDIVALI EAST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400101 28855560, 9029069566 DAHANUKARWADI, 1,2 & 3, Kamalvan, Junction of Link Road, M.G. 10 KANDIVALI WEST Noble Plus Road, Kandivali (W), Mumbai -400067 28682349, 9029069568 #2,Tanna Kutir,17th Roaad,Next to Neelam 11 17TH ROAD, KHAR WEST Noble Plus Foodland,, 17th Rd, Khar West, Mumbai-52. 26047777, 8433915319 #2,Mahesh Society, 3rd TPS, 5th Road, Khar 12 5TH ROAD, KHAR WEST Noble Plus West, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400052 26492222, 7718805146 VEER SAVARKAR MARG, 3, West wind, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim West, 13 MAHIM Noble Plus Mumbai, Maharashtra 400016 24444141, 7718806673 Heera panna mall, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra 14 A. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Hotel List 19.03.21.Xlsx

QUARANTINE FACILITIES AVAILABLE AS BELOW (Rate inclusive of Taxes and Three Meals) NO. DISTRICT CATEGORY NAME OF THE HOTEL ADDRESS SINGLE DOUBLE VACANCY POC CONTACT NUMBER FIVE STAR HOTELS 1 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hilton Andheri (East) 3449 3949 171 Sandesh 9833741347 2 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star ITC Maratha Andheri (East) 3449 3949 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 3 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hyatt Regency Andheri (East) 3499 3999 300 Prashant Khanna 9920258787 4 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Waterstones Hotel Andheri (East) 3500 4000 25 Hanosh 9867505283 5 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Renaissance Powai 3600 3600 180 Duty Manager 9930863463 6 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Orchid Vile Parle (East) 3699 4250 92 Sunita 9169166789 7 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sun-N- Sand Juhu, Mumbai 3700 4200 50 Kumar 9930220932 8 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star The Lalit Andheri (East) 3750 4000 156 Vaibhav 9987603147 9 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Park Mumbai Juhu Juhu tara Rd. Juhu 3800 4300 26 Rushikesh Kakad 8976352959 10 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sofitel Mumbai BKC BKC 3899 4299 256 Nithin 9167391122 11 Mumbai City 5 Star ITC Grand Central Parel 3900 4400 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 12 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Svenska Design Hotels SAB TV Rd. Andheri West 3999 4499 20 Sandesh More 9167707031 13 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Meluha The Fern Hiranandani Powai 4000 5000 70 Duty Manager 9664413290 14 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Grand Hyatt Santacruz East 4000 4500 120 Sonale 8657443495 15 Mumbai City 5 Star Taj Mahal Palace (Tower) Colaba 4000 4500 81 Shaheen 9769863430 16 Mumbai City 5 Star President, Mumbai Colaba -

Chief Minister to Inaugurate Eastern Freeway on June 13Th!

Chief Minister to inaugurate Eastern Freeway on June 13 th 13.59-km long Freeway reduces travel time and fuel Mumbaikars will travel from CST to Chembur in 25 minutes Will ease traffic congestion in Chembur, Sion and Dadar Mumbai, June 11, 2013 – The Chief Minister of Maharashtra Mr.Prithviraj Chavan will inaugurate the crucial Eastern Freeway on Thursday, June 13, 2013, at 3 p.m. along with Anik-Panjarpol Link Road. The 13.59-km signal- free stretch will ease traffic congestion in Chembur, Sion and Dadar areas and will reduce travel time from Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus to Chembur to a mere 25 minutes. The Freeway will also provide the much needed speedy connectivity from the Island city to the eastern suburbs and to Navi Mumbai, Panvel, Pune and Goa. The project throws up a highlight that will make motorists happy. While the 9.29-km Eastern Freeway will be entirely elevated, the 4.3-km Anik-Panjarpol Link Road provides for a 550-meter long twin tunnel – first of its kind in urban setup of our country. Present on the occasion will be Mr. Milind Deora, Hon.Minister of State for Communication and Information Technology, Government of India, New Delhi; Mr. Ajit Pawar, Hon.Deputy Chief Minister, Maharashtra State; Mr. Jayant Patil, Hon.Minister for Rural Development and Guardian Minister, Mumbai City District, Mr.Mohd.Arif Naseem Khan, Hon.Minister for Textile and Guardian Minister, Mumbai Suburban District; Mr. Sunil Prabhu, Hon.Mayor, Mumbai; Mr.Eknath Gaikwad, Hon.MP, among other VIPs. The inauguration will take place at Orange Gate, P.D’Mello Road, Mumbai. -

Mindscapes of Space, Power and Value in Mumbai

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2014, pp. 277-292 The epistemology of a sea view: mindscapes of space, power and value in Mumbai Ramanathan Swaminathan Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation (ORF) Fellow, National Internet Exchange of India (NIXI) Contributing Editor, Governance Now [email protected] ABSTRACT: Mumbai is a collection of seven islands strung together by a historically layered process of reclamation, migration and resettlement. The built landscape reflects the unique geographical characteristics of Mumbai’s archipelagic nature. This paper first explores the material, non-material and epistemological contours of space in Mumbai. It establishes that the physical contouring of space through institutional, administrative and non-institutional mechanisms are architected by complex notions of distance from the city’s coasts. Second, the paper unravels the unique discursive strands of space, spatiality and territoriality of Mumbai. It builds the case that the city’s collective imaginary of value is foundationally linked to the archipelagic nature of the city. Third, the paper deconstructs the complex power dynamics how a sea view turns into a gaze: one that is at once a point of view as it is a factor that provides physical and mental form to space. In conclusion, the paper makes the case that the mindscapes of space, value and power in Mumbai have archipelagic material foundations. Keywords : archipelago, form, island, mindscape, Mumbai, power, space, value © 2014 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction: unearthing the archipelagic historiography of Mumbai A city can best be described as a collection of spaces. Not in any ontological sense or in a physically linear form, but in an ever-changing, ever-interacting mesh of spatialities and territorialities that display the relative social relations of power existing at that particular point in time (Holstein & Appadurai, 1989). -

Thane District NSR & DIT Kits 15.10.2016

Thane district UID Aadhar Kit Information SNO EA District Taluka MCORP / BDO Operator-1 Operator_id Operator-1 Present address VLE VLE Name Name Name Mobile where machine Name Mobile number working (only For PEC) number 1 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_akashS 7507463709 /9321285540 prithvi enterpriss defence colony ambernath east Akash Suraj Gupta 7507463709 Consultancy AMBARNATH thane 421502 Maharastra /9321285540 2 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_abhisk 8689886830 At new newali Nalea near pundlile Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH Maharastraatre school, post-mangrul, Telulea, Ambernath. Thane,Maharastra-421502 3 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_sashyam 9158422335 Plot No.901 Trivevi bhavan, Defence Colony near Rakesh Sashyam GUPta 9158422335 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ayyappa temple, Ambernath, Thane, Maharastra- 421502 4 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_pandey 9820270413 Agrawal Travels NL/11/02, sector-11 ear Sandeep Pandey 9820270413 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ambamata mumbai, Thane,Maharastra-400706 5 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO pahal_abhs 8689886830 Shree swami samath Entreprises nevalinaka, Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH mangrul, Ambarnath, Thane,Maharastra-421301 6 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS055808 9637755100/8422883379 Shop No.1, Behind Datta Mandir Durga Devi Pada Priyanka Wadekar 9637755100/ AMBARNATH /VLE_MCR610_NS073201 Old Ambernath, East 421501 8422883379 7 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS076230 9324034090 / Aries Apt. Shop No. 3, Behind Bethel Church, Prashant Shamrao Patil 9324034090 / AMBARNATH 8693023777 Panvelkar Campus Road, Ambernath West, 8693023777 421505 8 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS086671 9960261090 Shop No. 32, Building No. 1/E, Matoshree Nagar, Babu Narsappa Boske 9960261090 AMBARNATH Ambarnath West - 421501 9 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS037707 9702186854 House No. -

Naigaon (Khairgaon) District: Nanded

Mudkhed Village Map Takli(T.B.) Dharmabad Taluka: Naigaon (Khairgaon) District: Nanded Vanzirgaon Loha Barbada Umri Mamnyal Manur Tarf Ba Izatgaon (M) Patoda (T.B.) Antargaon Kahala Bk. Izatgaon Bk Sadakpur µ 2.5 1.25 0 2.5 5 7.5 Kahala Kh Mandni km Rui Bk Kushanoor Sawarkhed Rui Kh Sategaon Somthana Location Index Vanjarwadi Ikalimal Dharmabad Babulgaon Ghungrala Melgaon Hiparga (Janerao) Nilegavhan Sangvi Dhanaj District Index Kuntoor Nandurbar Bhandara Narangal Dhule Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Jalgaon Ransugaon Paradwadi Takbid Akola Wardha Hussa Buldana Ancholi Nashik Washim Chandrapur Yavatmal Aurangabad Degaon Charwadi Raher Palghar Salegaon Jalna Hingoli Gadchiroli Kolambi Talbid Takalgaon Thane Ahmednagar Parbhani Mumbai Suburban Nanded Palasgaon Mumbai Bid Godamgaon Kokalegaon Hangraga Raigarh Pune Latur Bidar Lalwandi Osmanabad Awrala Satara Solapur Kauthala Daregaon Naigaonwadi Ratnagiri Shelgaon Chatri Sangli Sujlegaon Maharashtra State Naigaon Kolhapur Manjram Iklimore NAIGAON Sindhudurg Kandhar Bendri !( Dharwad Khairgaon Betak Biloli Manjramwadi Pimpalgaon (Na) Taluka Index Mustapur Mahoor Kinwat Mokasdara Khandgaon Gadga Hotala Kedar Wadgaon Hadgaon Himayatnagar Kopra Narsi Ardhapur Nawandi Bhokar NandedMudkhed Marwali Tanda Loha Umri Aluwadgaon Kandala Biloli Marwali Dharmabad Naigaon (Khairgaon) Kandhar Tembhurni Biloli Legend Mukhed Deglur !( Taluka Head Quarter Dhanora T.M. Ratoli Kuncholi Mugaon Karla T.M. Dhuppa Railway District: Nanded Takli(T.M.) Mahegaon National Highway State Highway Village maps from Land Record Department, GoM. Bhopala Data Source: Shelgaon (Gauri) State Boundary Waterbody/River from Satellite Imagery. District Boundary Generated By: Mukhed Takli Bk. Taluka Boundary Maharashtra Remote Sensing Applications Centre Village Boundary Autonomous Body of Planning Department, Government of Maharashtra, VNIT Campus, Waterbody/River South Am bazari Road, Nagpur 440 010.