Jaunpur.Pdf 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of INDIAN CITIES on RIVERS (India)

List of important cities on river (India) The following is a list of the cities in India through which major rivers flow. S.No. City River State 1 Gangakhed Godavari Maharashtra 2 Agra Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 3 Ahmedabad Sabarmati Gujarat 4 At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Allahabad Uttar Pradesh Saraswati 5 Ayodhya Sarayu Uttar Pradesh 6 Badrinath Alaknanda Uttarakhand 7 Banki Mahanadi Odisha 8 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 9 Baranagar Ganges West Bengal 10 Brahmapur Rushikulya Odisha 11 Chhatrapur Rushikulya Odisha 12 Bhagalpur Ganges Bihar 13 Kolkata Hooghly West Bengal 14 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 15 New Delhi Yamuna Delhi 16 Dibrugarh Brahmaputra Assam 17 Deesa Banas Gujarat 18 Ferozpur Sutlej Punjab 19 Guwahati Brahmaputra Assam 20 Haridwar Ganges Uttarakhand 21 Hyderabad Musi Telangana 22 Jabalpur Narmada Madhya Pradesh 23 Kanpur Ganges Uttar Pradesh 24 Kota Chambal Rajasthan 25 Jammu Tawi Jammu & Kashmir 26 Jaunpur Gomti Uttar Pradesh 27 Patna Ganges Bihar 28 Rajahmundry Godavari Andhra Pradesh 29 Srinagar Jhelum Jammu & Kashmir 30 Surat Tapi Gujarat 31 Varanasi Ganges Uttar Pradesh 32 Vijayawada Krishna Andhra Pradesh 33 Vadodara Vishwamitri Gujarat 1 Source – Wikipedia S.No. City River State 34 Mathura Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 35 Modasa Mazum Gujarat 36 Mirzapur Ganga Uttar Pradesh 37 Morbi Machchu Gujarat 38 Auraiya Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 39 Etawah Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 40 Bangalore Vrishabhavathi Karnataka 41 Farrukhabad Ganges Uttar Pradesh 42 Rangpo Teesta Sikkim 43 Rajkot Aji Gujarat 44 Gaya Falgu (Neeranjana) Bihar 45 Fatehgarh Ganges -

News Letter Dec. 2019

KAS S I AM V I N T A I JVS J SAMACHAR OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2019 VOLUME 3 ISSUE 19 EMPOWERING YOUNGSTERS WITH DISABILITIES THROUGH SKILL TRAINING Key Highlights With the aim to equip youngsters with disabilities with skills, JVS successfully 9 local schools in Harahua completed three months’residential course on block in Varanasi, U.P came ‘Food and Beverage Service Management’. together under the guidance 19 out of 20 young adults with disabilities of JVS to form School completed the training, followed by Implementation and assessment and certification by AKG Monitoring Committee SKILLS Pvt. Ltd. duly recognized by Skill India, empanelled with Ministry of Skill (SIMC) India, empanelled with Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship Govt. of India. 15 out of 19 are placed, some of them in star hotels for on the job training and others earning a decent income in hospitality industry. Ankit Kumar, placed as trainee steward in Tridev Hotel Varanasi says, “Now I have regained my confidence and am Creating Disability Cell in able to live independently including financial independency”. Ankit Kumar political parties has taken (Steward, Tridev Hotel) a momentums with the AWARENESS RALLY FOR COMMUNITY RESPONSE ON HIV campaign initiated on the Community awareness plays a vital role in International Day of preventing HIV/AIDs. JVS sensitized the Persons with Disabilities local community on the problem by organizing an awareness rally on the occasion of World Aids Day on December 01, 2019. 15 youth with disability After the rally, a discussion was held with have begun their On the about 130 participants, who were mostly job training in star members of Self Help Groups, on prevention hotels in Varanasi after and treatment of HIV and its associated health completing course on complications. -

Academic Course Prospectus for the Session 2012-13

PROSPECTUS 2012-13 With Application Form for Admission Secondary and Senior Secondary Courses fo|k/kue~loZ/kuaiz/kkue~ NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OPEN SCHOOLING (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA-201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in Learner Support Centre Toll Free No.: 1800 180 9393, E-mail: [email protected] NIOS: The Largest Open Schooling System in the World and an Examination Board of Government of India at par with CBSE/CISCE Reasons to Make National Institute of Open Schooling Your Choice 1. Freedom To Learn With a motto to 'reach out and reach all', NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn i.e., what to learn, when to learn, how to learn and when to appear in the examination is decided by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of learning. 2. Flexibility The NIOS provides flexibility with respect to : • Choice of Subjects: You can choose subjects of your choice from the given list keeping in view the passing criteria. • Admission: You can take admission Online under various streams or through Study Centres at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels. • Examination: Public Examinations are held twice a year. Nine examination chances are offered in five years. You can take any examination during this period when you are well prepared and avail the facility of credit accumulation also. • On Demand Examination: You can also appear in the On-Demand Examination (ODES) of NIOS at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels at the Headquarter at NOIDA and All Regional Centres as and when you are ready for the examination after first public examination. -

VIKLANG PENSION RULAR.Xlsx

fnO;kaxtu ia's ku uohu Lohd`fr xzkeh.k {ksrz foRrh; o"kZ 2019&20 S.No. Block Panchayat Village Register No. Name as Per Digitally Bank Account Deatil Name As Per PFMS Father/Husband Signed by District Name Officer STATE BANK OF INDIA /BRAHMANPUR BARKHANDI 1 BADLA PUR Baluwa Balua 315810354213 MANOJ KUMAR BIND Mr. MANOJ KUMAR BIND JAYNATH BIND /31233412443 /SBIN0012500 UNION BANK OF INDIA /PURANI BAZAR (BADLAPUR) RADHANA DEVI WO 2 BADLA PUR Baluwa Himmatpur 315810355523 SHAILENDRA SATISH CHANDRA /475602010260215 /UBIN0547565 SHAILENDRA KUMAR UNION BANK OF INDIA /SINGRAMAU ANIL KUMAR SO 3 BADLA PUR Bhula Bhula 315810000000 ANIL KUMAR HARISHCHAND /363602011015413 /UBIN0536369 HARISHCHAND KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /SHAHPUR GANGADEEN SO JAGGU JAGGURAM 4 BADLA PUR Birbhanpur Mureedpur 315810235013 GANGADEEN PRAJAPATI /414522080004142 /UBIN0RRBKGS PRAJAPATI PRAJAPATI UNION BANK OF INDIA /GHANSHYAMPUR 5 BADLA PUR Budenepur Budhanepur 315810346493 PRATIMA PRATIMA MOHAN PRAJAPATI /399902120002354 /UBIN0539996 KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /SHAHPUR 6 BADLA PUR Chandapur Chandapur 315810351693 KAVITA KAVITA NARENDRA KUMAR /414332080006408 /UBIN0RRBKGS UNION BANK OF INDIA /GHANSHYAMPUR 7 BADLA PUR Dadawa Dadawa 315810355023 ROSHANI ROSHANI KHARBHAN /399902120008516 /UBIN0539996 KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /BAHERIPUR RAJESH KUMAR SINGH SO 8 BADLA PUR Jamaupatti Jamaupatti 315810350563 RAJESH SINGH YADUVEER SINGH /414242010056909 /UBIN0RRBKGS YADUVEER SINGH KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /BAHERIPUR VANSRAJ SO RAM KISHOR 9 BADLA PUR Jamaupatti Jamaupatti 315810347993 VANSHARAJ RAM KISHOR /414242010056666 /UBIN0RRBKGS MAURYA KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /BAHERIPUR 10 BADLA PUR Kachhaura Kachhaura 315810345893 RAM GIRI RAM GIRI SO RAMNAYAN RAJ NAYAN /414242010008485 /UBIN0RRBKGS KASHI GOMTI SAMYUT GRAMIN BANK /BAHERIPUR HASHILA PRASADGUPTA 11 BADLA PUR Kachhaura Kanakpur 315810347923 HAUSHILAA PRASAD GUPTA RAMPHER GUPTA /414242010004943 /UBIN0RRBKGS SORAMPHERGUPTA STATE BANK OF INDIA /BADLAPUR /34538825281 12 BADLA PUR Kaveli Pahitiyapur 315810361343 ARCHNA Mrs. -

ASHA Database Jaunpur Name of Name of ID No.Of Population S.No

ASHA Database Jaunpur Name Of Name Of ID No.of Population S.No. Name Of Block Name Of Sub-Centre Name Of ASHA Husband's Name Name Of Village District CHC/BPHC ASHA Covered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801001 Smt. Amreesha Yadav Sri Mahendra Kumar Yadav Sarokhanpur 1156 2 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Gonauli 3801002 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Rakesh Sarhapur 1302 3 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Gopalapur 3801003 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Subhash Chandra Gopalapur 1000 4 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Mirshadpur 3801004 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Virendra Yadav Muradpur Kotila 1089 5 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Merha 3801005 Smt. Aneeta Devi Sri Ramashray Nawik Gaura 1000 6 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Dandawa 3801006 Smt. Aneeta Gupta Sri Badelal Gupta Khalishpur 1094 7 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center II 3801007 Smt. Aneeta Kahar Sri Vijay Kahar Bhaluahin 1000 8 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Singramau II 3801008 Smt. Aparna Tiwari Sri Manoj Kumar Tiwari Bahur 1000 9 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801009 Smt. Archana Gupta Sri Subhash chandra Gupta Sultanpur 1108 10 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Fattupur 3801010 Smt. Archana Trigunait Sri Manoj Trigunait Vithua Kala 1024 11 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Hariharpur 3801011 Smt. Arti Devi Sri Harish chand Kevtali Kala 1000 12 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Ramanipur 3801012 Smt. Aruna Devi Sri Rakesh Kumar Gupta Rautpur 1000 13 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Ghanshyampur 3801013 Smt. Asha Devi Sri Sikandar Jagatpur 1299 14 Jaunpur BADLAPUR CHC BADLAPUR Main Center I 3801014 Smt. -

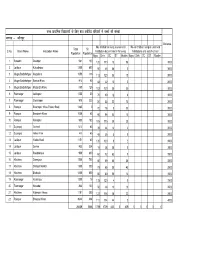

Ky;Ksa Ds Fy, Ik= Vlsfor Cflr;Ksa Esa Cppksa Dh La[;K Tuin & Tksuiqj Distance No

mPp izkFkfed fo|ky;ksa ds fy, ik= vlsfor cfLr;ksa esa cPpksa dh la[;k tuin & tkSuiqj Distance No. of children living in unserved No. of children living in unserved Total Sc S.No. Block Name Habitation Name habitation but enrolled in far away habitations and out of school Population Population Boys Girls SC ST Muslim Boys Girls SC ST Muslim 1 Barsathi Daudpur 981 100 120 110 10 98 3000 2 Jalalpur Kukudhipur 1200 600 50 45 68 0 3000 3 Mugra Badshahpur Nargahna 1050 385 112 120 38 13 3000 4 Mugra Badshahpur Bankat Khas 912 90 43 42 10 5 3000 5 Mugra Badshahpur Madardih Khas 850 125 102 120 30 35 3000 6 Ramnagar Lakhapur 1255 50 70 60 12 6 3000 7 Ramnagar Shekhapur 970 225 50 55 22 75 3000 8 Rampur Bharthipur Khas Thakur Basti 1465 0 70 78 0 30 3000 9 Rampur Banideeh Khas 1000 80 90 95 20 15 3000 10 Rampur Naharpur 955 180 105 115 25 20 3000 11 Sujanganj Gauhani 1210 60 39 44 12 2 3000 12 Sujanganj Vidhan Pura 830 45 45 35 5 0 3000 13 Jalalpur Yadav Basti 1151 40 128 120 8 2 3500 14 Jalalpur Derwa 922 234 19 26 36 0 3500 15 Jalalpur Raedhanpur 900 600 60 52 62 0 3500 16 Khuthan Samsipur 1500 700 80 69 65 36 3500 17 Khuthan Dhirauli Nankar 1300 300 78 65 35 45 3500 18 Khuthan Bhatauli 1800 600 80 60 59 12 3500 19 Ramnagar Hushinpur 1300 18 135 120 4 0 3500 20 Ramnagar Nevada I 833 100 50 46 10 10 3500 21 Khuthan Nijampur Khass 1181 200 122 118 48 22 3800 22 Rampur Bhanpur Khas 3044 334 111 114 44 3 4000 26609 5066 1759 1709 623 0 429 0 0 0 0 0 izkFkfed fo|ky;ksa ds fy, ik= vlsfor cfLr;ksa esa cPpksa dh la[;k tuin & tkSuiqj No. -

MATH-SC- FINAL.Xlsx

BLOCK TEACHER NIYOJAN 2019-2021 NIYOJAN UNIT: BLOCK-TARARI PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST DIST:-BHOJPUR CLASS 6 TO 8 SUBJECT: MATH-SCIENCE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Training T.T Matric Inter Graduation Total B.TeT/C.TeT (BT,B.Ed,D.El.Ed) et App. Disa Catoge Obtai Obta Obta Obta Percenta Obt TET/CTET Total Sr. No. Applicant Name Father's NameAddress Date of Birth Full Full Full Full Full W Remarks Sr. No. bility ory/sex ned Perce ined Perce ined Perce ined Percen ge aine Perce Roll No Merit Mark Mark Mark Mark Mar eig Mark ntage Mar ntage Mar ntage Mark tage Average d ntage s s s s ks ht s ks ks s Mar PRASHANT PROMOD KUMAR VILL-SKAMININAGAR, PO+PS- 1 1854 BIKRAMGANJ 10-10-1995 UR/M 500 445 89.00 500 450 90.00 2800 2387 85.25 1500 1155 77.00 85.31 150 99 66.00 2 1502034 87.31 KUMAR PANDEY PANDEY DISTT-ROHTAS-802212 RAHUL KUMAR LAHERI, PO-BASIKALLA, PS-DINARA, 2 1843 MUNNA SHAW DISTT-ROHTAS 10-02-1994 EBC/M 500 445 89.00 500 437 87.40 2800 2250 80.36 3400 2672 78.59 83.84 150 89 59.33 2 8400493 85.84 SHAW 802129 DINESH PATI VILL-CHAMTODAR,POST-BISI 3 1013 AKASH TIWARI 13-02-1994 UR M 600 496 82.67 500 444 88.80 1800 1310 72.78 3200 2892 90.38 83.65 150 96 64.00 2 195088946 85.65 TIWARI KALAN ,DIST-BHADOHI(UP) BIRENDRA VILL-KATALPUR, PO-BAHUARA, PS- 4 1850 BIPIN KUMAR NAWANGAR 02-08-1994 UR/M 500 470 94.00 500 428 85.60 2800 2156 77.00 1500 1170 78.00 83.65 150 102 68.00 2 700436 85.65 KUMAR SINGH DISTT-BUXAR-802216 VILL-CHITRAGUPT COLONY, PO+PS- 5 1853 RAHUL SINGH RAKESH SINGH BIKRAMGANJ 10-05-1995 -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Varanasi District, U.P

GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-13) By J.P. Gautam Scientist 'C' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. VARANASI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................5 2.0 PHYSIOGRAPHY ..................5 3.0 GEOLOGY ..................5 3.1 Sub-Surface Geology 4.0 HYDROMETROLOGY ..................6 5.0 HYDROGEOLOGY ..................7 5.1 Hydrogeological Setup 5.2 Ground Water Condition 5.3 Long Term Water Level Trend 5.4 Ground Water Resources 5.5 Ground Water Exploration 6.0 GROUND WATER QUALTIY ..................13 6.1 Quality of Shallow Ground Water 6.2 Quality of Deeper Aquifer 7.0 GROUND WATER PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED ..................13 7.1 Water Table Depletion 8.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................13 9.0 CONCLUSIONS ..................14 10.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................14 PLATES: 1.0 INDEX MAP OF VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. 2.0 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL PREMONSOON 2012, VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. 3.0 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL POSTMONSOON 2012 VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. 4.0 GROUND WATER RESOURCE AND DRAFT OF VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. 5.0 GROUND WATER EXPLORATION MAP OF VARANASI DISTRICT, U.P. 2 VARANASI DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION District : Varanasi Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 1578 Sub Division a) Number of Tehsil : 02 Varanasi Sadar & Pindra b) Number of Block : 08 Population (as on 2011 census) : 3682194 Male : 1928641 Female : 1753553 Decadal Growth of Population : 23.84% 2. CLIMATOLOGICAL DATA Normal Rainfall (mm) : 997.40 Mean Maximum Temperature : 44.000C Mean Minimum Temperature : 5.200C Average R. Humidity : 56% Number of Rainy Days : 58 Wind Speed Maximum : 4.5 Km./Hr. -

ISLAMIC-MONUMENTS.Pdf

1 The Masjid-i Jami of Herat, the city's first congregational mosque, was built on the site of two smaller Zoroastrian fire temples that were destroyed by earthquake and fire. A mosque construction was started by the Ghurid ruler Ghiyas ad-Din Ghori in 1200 (597 AH), and, after his death, the building was continued by his brother and successor Muhammad of Ghor. In 1221, Genghis Khan conquered the province, and along with much of Herat, the small building fell into ruin. It wasn't until after 1245, under Shams al-Din Kart that any rebuilding programs were undertaken, and construction on the mosque was not started until 1306. However, a devastating earthquake in 1364 left the building almost completely destroyed, although some attempt was made to rebuild it. After 1397, the Timurid rulers redirected Herat's growth towards the northern part of the city. This suburbanization and the building of a new congregational mosque in Gawhar Shad's Musalla marked the end of the Masjid Jami's patronage by a monarchy. 2 This mosque was constructed in 1888 and was the first mosque in any Australian capital city. It has four minarets which were built in 1903 for 150 pounds by local cameleers with some help from Islamic sponsors from Melbourne. Its founding members lie in the quiet part of the South West corner of the city. 3 The Cyprus Turkish Islamic Community of Victoria was established in Richmond, Clifton Hill, and was then relocated to Ballarat Road, Sunshine in 1985 The Sunshine Mosque is the biggest Mosque in Victoria, and has extended its services to cater for ladies, elderly and youth groups. -

Fpo 2006) As of 05.07.2019

LIST OF UNCLAIMED SHARES (FPO 2006) AS OF 05.07.2019 The Bank had came out with Follow-on-Public Issue in the year 2006. The shares allotted to some of the applicants during this FPO were not creditted to their respective demat account due to various reasons. The list of such shareholders is given below. The shareholder/s whose name/s is/are appearing in this list are requested to approach the Bank or Registrar & Share Transfer Agent of the Bank for further guidance. SR. NAME Address-Line1 Address-Line2 Pincode NO. 1 A JAFARULLAKHAN 7/38 PALLIVASAL STREET EMANESWARAM 623701 2 A KRISHNAMURTHY 32 PASUPATHY STREET MAYILADUTHORAI 609001 3 A MAHESWAR REDDY 1-112-6/1 SECTOR 12 MVP COLONY VISAKHAPATANAM 530013 4 ABDIL GAFFAR 86 NANANDANWAN COLONY MANIK B ROAD INDORE MP 452001 5 ABHIMANYA YADAV C H C BARSATHI PO SABASA JAUNPUR 000000 6 AFTAB ALAM MOHALLA SIPAH PO MUNGRA BADSHAHPUR DISTT JAUNPUR JAUNPUR 222202 7 AJAY NARAYAN SHRIVASTAVA VIJAY BANDHU NIWAS TALI WAIDHAN POST WAIDHAN DIST SIDNI M P 000000 8 AKHILESH SINGH 000000 9 AKHILESH SINGH 10 ALPA BHAVESH BAVISHI MOTICHAND KESHAVJI TAJNAPETH AKOLA 000000 11 ALPANA KATIYAR 11 NEW CIVIL LINES LAKHANPUR KANPUR 208019 12 AMBIKA SINGH YADAV AT DHAMARAW PO TIRCHHI DIST GHAZIPUR GHAZIPUR 000000 13 AMIT MALIK B - 4 / 90 V. P.O. MAHILPUR HOSHIARPUR HOSHIARPUR 146105 14 ANIL KUMAR GUPTA C/O RAJA RAM & SONS JAHANGEERABAD JAUNPUR UTTAR PRADESH 000000 15 ANIL KUMAR PUSHKARNA 29 NARAIN NAGAR B SHEIKH ROAD JALANDHAR 16 ANITA MORESHWAR SAHASRABUDHE NEAR DKT H SCHOOL ICHALKARANJI 416115 17 ANJANI KUMAR SINGH -

Uttar Pradesh

District Tehsil/Man States Name dal/Block Address Uttar Bhadohi Aurai VILLAGE DURASI,POST BARAWA BAZAR,AURAI, Pradesh Uttar Bhadohi Bhadohi Pradesh MASUDI DURGAGANJ BHADOHI Uttar Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhikhamapur,Ekauni,bhadohi,Suriyawan Pradesh Uttar Bhadohi Gyanpur BAYAWAN BAYAWAN OZH, GYANPUR BHADOHI Pradesh Uttar Bhadohi Gyanpur Mishra Market First Floor,Beside Post Office,Gyanpur, Pradesh Uttar Bhadohi Bhadohi Pradesh DEVNATH PUR LAKSHAMAN PATTI SANT RAVIDAS NAGAR Uttar Lalitpur Lalitpur Gram Bangariya,Post Pataua Pali 284403 Pradesh Uttar Lalitpur Mehroni Lalitpur Road ,Mehroni Pradesh Uttar VIL + POST -LADWARI PS. -BAR . BLOCK- BAR TAH.- TALBEHAT Lalitpur Pali Pradesh DIST.-LALITPUR U.P. PIN. 284123, Uttar Lalitpur Madawra Post Madawara,Thana Madawara,Lalitpur Pradesh Uttar Lalitpur Talbehat Infront of tehsil Talbehat,Lalitpur-284126 Pradesh Uttar Choka Bag ,Rawatiyana Mohalla,Narsingh Vidhya Mandir Ke Lalitpur Lalitpur Pradesh Peeche Uttar VILL AND POST BARASARA BLOCK KARANDA GHAZIPUR Ghazipur Ghazipur Pradesh GHAZIPUR GHAZIPUR UTTAR PRADESH 233232 Uttar Ghazipur Ghazipur VILL- GOVINDPUR KIRAT, POST-GOVINDPUR, GHAZIPUR, Pradesh Uttar Ghazipur Ghazipur VILL- GANNAPUR, POST- BIRNO, GHAZIPUR, Pradesh Uttar Ghazipur Jakhnia 177 Jakhania Jakhanian jakhaniya 275203 Pradesh Uttar Ghazipur Jakhnia GHAZIPUR,VILL MANIHARI Pradesh Uttar Ghazipur Kasimabad Shekhanpur Mohammadabad KASIMABAD GHAZIPUR Pradesh HANABHANWARKOL Uttar Muhammdaba Ghazipur TEHSILMOHAMMADABADPOSTLOHARPURVILLLOHARPUR Pradesh d MOHAMMADAB GHAZIPUR233231 Uttar Muhammdaba Ghazipur