Page 1 the WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scouting at the Olympics Boy Scouts and Girl Guides As Olympic Volunteers 1912-1998* ------Roland Renson —

Scouting at the Olympics Boy Scouts and Girl Guides as Olympic Volunteers 1912-1998* -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Roland Renson — n 1894, Pierre de Coubertin created the modern I Olympic movement and Robert Baden-Powell founded the Boy Scout movement in 1908. Both were educational innovators and creators of universal movements, which aspired to international peace and brotherhood. Although both men were convinced patriots, they shared common ideas about idealistic internationalism. Several idealis tic international movements made their appearance in the fin de siècle period, namely the Red Cross (1863), the Esperanto movement (1887), the Olympic movement (1894) and Scouting (1907). The Olympic movement and the Scouting movement were originally exclusively male organizations, which adopted the ideology of chivalry as Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937) founded the modern Olympic movement the basis for establishing an idealized transnational iden in 1894 and - which is little known - the 'neutral' scout federation Eclaireurs tity (Hoberman 1995). Coubertin was cofounder in 1910 Français in France in 1911 (Painting by Gaétan de Navacelle, courtesy of - with the physicist and winner of the 1908 Nobel-Prize Comité National Olympique et Sportif Français, Paris, in Müller 2000:5). Gabriel Lippmann - of the Ligue d’Education National, the forerunner of the French Boy Scouts and one year later, he founded the neutral’ scouting organization Eclaireurs Français (EF) in 1911 (Kruger 1980). Baden-Powell - like many other Edwardians - was haunted by fears that the British race was deteriorating, both physically and morally, and he therefore promoted outdoor life and the British ideology of sportsmanship, which was also absorbed by Coubertin (Brendon 1979: 239; Rosenthal 1986: 10; 31). -

The County Executive Committee

The County Executive Committee (References to County also applies to Areas, Regions, Islands and Bailiwicks) FS330079 October/2015 Edition no 5 (103402) 0845 300 1818 The County Executive Committee plays a vital Appoint and manage the operation of any sub- role in the running of a Scout County. Executive Committees, including appointing Chairmen to Committees make decisions and carry out lead the sub-committees. administrative tasks to ensure that the best quality Ensure that Young People are meaningfully Scouting can be delivered to young people in the involved in decision making at all levels within County. the County. The opening, closure and amalgamation of This factsheet should be treated as a guide and Districts and Scout Active Support Units in the read in conjunction with other resources (including County as necessary. The Scout Association’s Policy, Organisation and Appoint and manage the operation of an Rules referred to as POR throughout this Appointments Advisory Committee, including factsheet). appointing an Appointments Committee Chairman to lead it. Further details of the responsibilities of the County Executive Committee can be found in chapters 5 The Executive Committee must also: and 13 of POR. Note that SV in this factsheet Appoint Administrators, Advisers, and Co-opted denotes there is a Scottish variation to that members of the Executive Committee. section of guidance. Approve the Annual Report and Annual Accounts after their examination by an The County Executive Committee appropriate auditor, independent examiner or The Executive Committee exists to support the scrutineer. County Commissioner in meeting the Present the Annual Report and Annual Accounts responsibilities of their appointment. -

Here Come the Scouts

HERE C ME THE SCOUTS! By Diana Kile Green DNR WV World-class outdoor recreation opportunities, includ- ing zip-lining, are in store for Boy Scouts at the Summit Bechtel Reserve in Fayette County. © Mike Roytek 4 OctoberCopyright 2012 . www.wonderfulwv.com Travel DNR WV Aerial view of the 10,600-acre Summit under construction © Gary Hartley et ready, West Virginia. The Boy to have spectacular natural beauty and water for recreational Scouts are coming—and coming in activities, and to be at least 5,000 acres in size, within 25 miles a big way. of interstate highways, near adequate medical facilities, and In July 2013, nearly 50,000 easy to get to year-round. scouts and their leaders, from every Then-Governor Joe Manchin appointed the West Virginia state in the union, will converge on Project Arrow Task Force, composed of state Development a brand new, world-class Boy Scout Office professionals, government officials, and private volun- facility in Fayette County. The oc- teers, to identify the best possible site in West Virginia and casion: the Boy Scouts of America’s 10-day National Jamboree. to coordinate efforts to land the facility. Steven McGowan, a GScouting’s premier event occurs every four years, and for the Charleston attorney who is also an Eagle Scout and a longtime next century West Virginia will be its home. In addition, in Scout volunteer, headed up the group. 2019, the new National Center for Scouting Excellence in Fayette County will host scouts and other visitors from more Intense Competition than 160 countries for the 24th World Scout Jamboree. -

THE SILVER ARROWHEAD PRESENTED for DISTINGUISHED SERVICE to the ORDER SINCE 1940 VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1 | SPRING 2015 Bradley E

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 | WINTER 2015 THE SILVER ARROWHEAD PRESENTED FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE TO THE ORDER SINCE 1940 VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1 | SPRING 2015 Bradley E. Haddock: Friend, Brother, Leader During lunch Brad noticed Dr. Goodman giving him his undivided attention, making him feel as if he were the most important person in the world. The second occurred during the 60th Anniversary Celebration at Treasure Island Scout Camp. Arriving late, Brad and National Vice Chief Eddie Stumler stood in the back of the audience behind two young Arrowmen during the opening flag ceremony. Unnoticed by the two, Brad and Eddie overheard their conversation. They wanted to meet and talk with the national officers, but they remained unsure how to introduce themselves. As the two turned around following the ceremony, they recognized the national officers and became tongue-tied. Brad and Eddie quickly introduced themselves and engaged the two young Arrowmen in conversation. Brad realized that as a leader, people should not have to come to you; you should go to them, be approachable, and make them feel comfortable. These unique experiences would be ones that Brad would Dr. E. Urner Goodman with Bradley Haddock at the 1975 National OA Conference. never forget, and ones he would often refer By TIMOTHY C. BROWN Ta-Wa-Ko-Ni in the Quivira Council, Brad found a back to in his future dealings with others. CLASS OF 2015 lifetime of opportunities in our Brotherhood of As a 16 year old Arrowman attending my Cheerful Service. first NOAC in 1975, I too had the good fortune It’s been said that as a leader you must Brad’s rise in the Order of the Arrow was of meeting National Chief Brad Haddock. -

Wood-Badge-Centenary Identity Guidelines.Pdf

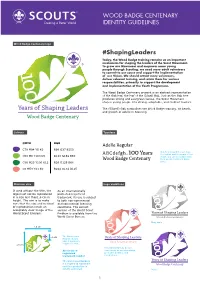

WOOD BADGE CENTENARY IDENTITY GUIDELINES Wood Badge Centenary logo #ShapingLeaders Today, the Wood Badge training remains as an important mechanism for shaping the leaders of the Scout Movement. To grow our Movement and empower more young people through Scouting, we need more adult volunteers to commit to our cause and support the implementation of our Vision. We should attract more volunteers, deliver relevant training, and retain them for various responsibilities, primarily to support the development and implementation of the Youth Programme. The Wood Badge Centenary artwork is an abstract representation of the Oak leaf, the leaf of the Gilwell Oak. Just as the Oak tree produces strong and evergreen leaves, the Scout Movement shapes young people into strong, adaptable, and resilient leaders. The (Gilwell) Oak symbolises the Wood Badge training, its beads, and growth of adults in Scouting. Colours Typeface CMYK RGB C79 M94 Y0 K0 R98 G37 B153 This font is used to reproduce the tagline and the name of the C50 M0 Y100 K5 R133 G189 B60 event, and can be downloaded from Google fonts and Adobe C86 M25 Y100 K12 R26 G129 B64 fonts. C0 M59 Y43 K0 R244 G134 B125 Minimun size Logo variations If used without the title, the As an internationally logo must not be reproduced protected registered in a size less than1.8 cm in trademark, its use is subject height. The aim is to make to both non-commercial sure that the size and method and commercial licensing of reproduction retain an conditions. The correct acceptably clear image of the version of the World Scout World Scout Emblem. -

Outdoor Adventure Skills – Scoutcraft

1 SCOUTCRAFT SKILLSS Competencies 1.1 I can hang a drying line at camp with a 1.6 I can name three wildflowers by half hitch or other knot. direct observation in a wild field, bush or forest. 1.2 I can keep my mess kit clean at camp. 1.7 I can gather dry, burnable wood for 1.3 When outdoors or at camp, I know a fire. what is drinkable (safe) and not drinkable (unsafe) water, and to check 1.8 I know to tell adults where I am going with a Scouter when I am unsure. when outdoors. 1.4 I know why it is important to stick to 1.9 I know how to keep a camp clean. trails when outdoors. 1.5 I know three reasons for having a shelter when sleeping outdoors. OUTDOOR ADVENTURE SKILLS OUTDOOR ADVENTURE Canadianpath.ca 2 SCOUTCRAFT SKILLSS Competencies 2.1 I can tie a reef knot, a round turn and two half-hitch knots. 2.2 I can cook a foil-wrapped meal in a fire. 2.3 I know how much water I should carry when on a hike or taking part in an 2.6 I have helped light a fire using only outdoor activity, and I know how to natural fire-starter materials found in carry the water. the forest, and I know the safety rules for when around a campfire. 2.4 I know what natural shelter materials or locations are to keep out of the 2.7 I know why it is important to use wind, rain, sun and snow, and where a buddy system when traveling in these may be found. -

The History of the Scout Wood Badge

The set of six wood beads belonging to Robert Baden-Powell The history of the Scout Wood Badge The Scouts (UK) Heritage Service December 2018 Since September 1919 adult volunteers in the Scouts have been awarded the Wood Badge on the completion of their leader training. The basic badge is made up of two wooden beads worn at the end of a leather lace. This iconic symbol of Scouting has become shrouded in myths and its origins and development confused. Having completed extensive research using the Scouts (UK) heritage collection we have pieced together the story. The components of the Wood Badge: The Wood Badge’s design took inspiration from a necklace brought back from Africa by Scouting’s Founder, Robert Baden-Powell. In 1888 Baden-Powell was serving with the British Army in Africa. During this period Baden-Powell visited an abandoned camp where Chief Dinizulu, a local chief had been based. In 1925 Baden-Powell recalled what he found, ’In the hut, which had been put up for Dinizulu to live in, I found among other things his necklace of wooden beads. I had in my possession a photograph of him taken a few months beforehand in which he was shown wearing this necklace round his neck and one shoulder.’1 Assuming the necklace was the same one as in the photo Baden-Powell took the necklace as a souvenir of the campaign and always referred to it as Dinizulu’s necklace. Baden- 1 How I obtained the necklace of Dinizulu, told by the Chief Scout, 1925 – the Baden-Powell papers Powell admired Dinizulu describing him as “full of resources, energy and pluck,” characteristics which he would later call upon Scouts to develop. -

Scouts Bsa Summer Camp Program Guide 2021

SCOUTS BSA SUMMER CAMP PROGRAM GUIDE 2021 RAINBOW SCOUT RESERVATION @RAINBOWSCOUTRESERVATION @RSRSUMMERCAMP “Our mission is to offer the finest summer camp experience in the region by providing a safe, quality, fun-filled Scouting program to every Scout and leader in camp.” This is accomplished by meeting the needs of the Troop Leaders, Scouts and their Families. CONTENTS WELCOME TO RSR! ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 WHAT’S NEW: ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 CAMP HEALTH PLANS: ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 DAILY SCHEDULE: .................................................................................................................................................................... 8 AQUATICS ................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 C.O.P.E./CLIMBING ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 ECOLOGY / CONSERVATION ................................................................................................................................................. -

RELIGIOUS EMBLEMS to Encourage Members to Grow Stronger in the Square Knot, Purple on Silver, No

R ELIGIOUS RELIGIOUS EMBLEMS To encourage members to grow stronger in The square knot, purple on silver, No. 5014, their faith, religious groups have developed the may be worn above the left pocket by adult following religious emblems programs. The members presented with the recognition. Adults E Boy Scouts of America has approved of these may wear both knots if they satisfy qualifying MBLEMS programs and allows the emblems to be worn criteria. When a square knot is worn, the medal on the official uniform. is not worn. Most religious emblems for Cub Scouts Generally, only one knot is worn, but any consist of a bar pin and pendant. Most religious combination of miniature devices may be worn emblems for Boy Scouts, Varsity Scouts, Sea on the same knot: Cub Scout, No. 604950; Scouts, and Venturers consist of a bar pin, Webelos Scout, No. 932; Boy Scout, No. 927; ribbon, and pendant. Varsity Scout, No. 928; Venturer, No. 930; The medal is worn pinned immediately above Sea Scout, No. 931. the seam of the left shirt pocket of the uniform. Additional information on religious The square knot, silver on purple, No. 5007, emblems is available from the BSA may be worn above the left pocket by a youth (www. scouting.org/awards/religiousawards) member or an adult member who earned the and P.R.A.Y (www.praypub.org). knot as a youth. Venturer, Sea Boy Scout Scout, Older and Boy Scout, Adult Cub Scout Webelos Scout Varsity Scout Varsity Scout Recognition African Methodist Episcopal Church God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service RELIGIOUS EMBLEMS | 77 Venturer, Sea Boy Scout Scout, Older and Boy Scout, Adult Cub Scout Webelos Scout Varsity Scout Varsity Scout Recognition Anglican Catholic Church The Order of Ad te Domine Ad te Domine Servus Dei Servus Dei St. -

The Life and Times of Scouting's Camp Madron

INTERNATIONAL SCOUTING COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION JOURNALVol 11, No. 2 June 2011 The Life and Times of Scouting’s Camp Madron ISCA JOURNAL - JUNE 2011 1 INTERNATIONAL SCOUTING COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION, INC CHAIRMAN PRESIDENT TERRY GROVE, 2048 Shadyhill Terr., Winter Park, FL 32792 CRAIG LEIGHTY, 4529 Coddington Loop #108, Wilmington, NC 8405 (321) 214-0056 [email protected] (910) 233-4693 [email protected] BOARD MEMBERS VICE PRESIDENTS: BILL LOEBLE, 685 Flat Rock Rd., Covington, GA 30014-0908, (770) 385-9296, [email protected] Activities BRUCE DORDICK, 916 Tannerie Run Rd., Ambler, PA 19002, (215) 628-8644 [email protected] Administration JAMES ELLIS, 405 Dublin Drive, Niles, MI 49120, (269) 683-1114, [email protected] Communications TOD JOHNSON, PO Box 10008, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96158, (650) 224-1400, Finance & Membership [email protected] DAVE THOMAS, 5335 Spring Valley Rd., Dallas, TX 75254, (972) 991-2121, [email protected] Legal JEF HECKINGER, P.O. Box 1492, Rockford, IL 61105, (815) 965-2121, [email protected] Marketing AREAS SERVED: GENE BERMAN, 8801 35th Avenue, Jackson Heights, NY 11372, (718) 458-2292, [email protected] BOB CYLKOWSKI, 1003 Hollycrest Dr., Champaign, IL 61821, (217) 778-8109, [email protected] KIRK DOAN, 1201 Walnut St., #2500, Kansas City, MO 64100, (816) 691-2600, [email protected] TRACY MESLER, 1205 Cooke St., Nocona, TX 76255, (940) 825-4438, [email protected] DAVE MINNIHAN, 2300 Fairview G202, Costa Mesa, CA 92626, (714) 641-4845, [email protected] JOHN PLEASANTS,1478 Old Coleridge Rd., Siler City, NC 27344, (919) 742-5199, Advertising Sales [email protected] TICO PEREZ, 919 Wald Rd., Orlando, FL 32806, (407) 857-6498, [email protected] JODY TUCKER, 4411 North 67th St., Kansas City, KS 66104, (913) 299-6692, Web Site Management [email protected] The International Scouting Collectors Association Journal, “The ISCA Journal,” (ISSN 1535-1092) is the official quarterly publication of the International Scouting Collectors Association, Inc. -

To Make Good Canadians: Girl Guiding in Indian Residential Schools

TO MAKE GOOD CANADIANS: GIRL GUIDING IN INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Mary Jane McCallum 2001 Canadian Studies and Native Studies M.A. Program May2002 ABSTRACT To Make Good Canadians: Girl Guiding in Indian Residential Schools Mary Jane McCallum Between 1910 and 1970, the Guide movement became active and, indeed, prolific in Indian residential, day, and hostel schools, sanatoriums, reserves and Northern communities throughout Canada. In these contexts, Guiding embraced not only twentieth century youth citizenship training schemes, but also the colonial project of making First Nations and Inuit people good citizens. But ironically, while the Guide programme endeavoured to produce moral, disciplined and patriotic girls who would be prepared to undertake home and civic responsibilities as dutiful mothers and wives, it also encouraged girls to study and imitate 'wild' Indians. This thesis will explore the ways in which Girl Guides prepared girls for citizenship, arguing that the Indian, who signified to Guides authentic adventure, primitive skills and civic duty, was a model for their training. 'Playing Indian' enabled Guides to access these 'authentic' Indian virtues. It also enabled them to deny their roles as proponents of colonialism. Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of people who have helped me to research and write this thesis. First, I would like to thank the Munsee Delaware First Nation for their continued assistance in my post-secondary academic endeavours. -

Wood Badge Generic Brochure.Pub

What is the purpose of Wood Badge? What are the qualifications? How do I register? The ultimate purpose of Wood Badge is to Wood Badge is not just for Scoutmasters. It’s Visit help adult leaders deliver the highest quality for adult Scouters at all levels: Cub Scouts, Boy http://www.pikespeakbsa.org/Event.aspx? Scouting program to young people and help Scouts, Varsity, Venturing, District and Council. id=1957 Review the event information, them achieve their highest potential. Youth older than 18 may attend and do not need then click on the register button. If you It models the best techniques for developing to be registered in an adult leadership role. Here need to make other arrangements for leadership and teamwork among both young are the qualifications: registration / payment, contact Steve people and adults. • Be a registered member of the BSA. Hayes at 719-494-7166 or • Complete basic training courses for your [email protected] How much time will Wood Badge primary Scouting position (see Scouting’s Basic A $50 payment is due at the time of take? Leader Training Courses at right). application. The first 48 fully paid Wood Badge is conducted over two three- • Complete the outdoor skills training Scouters who meet course requirements day weekends scheduled three weeks apart. program appropriate to your Scouting position. will be confirmed for the course. Each weekend begins at 7:30 a.m. Friday and • Be capable of functioning safely in an outdoor environment. What are the Training goes ‘til 4:00pm on Sunday. Your patrol will Prerequisites? have one or two meetings in between the • Complete the Colorado Boy Scout Camps course weekends.