Some Notes for Beginners – by Jim Bydie - Episode 1 (More Next Month) 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Illinois Orchid Society Newsletter

Central Illinois Orchid Society Newsletter May 2014 Vol. 8 no. 5, May 2014 In this Issue President's message President's message: Next meeting Spring has arrived, and our orchids must be very happy! I know mine are - there Events in the area is much blooming and rejoicing going on amongst them, and this is occurring Orchid of the month 1 despite my many absences since our first grandchild was born. I’ve traveled to New York several times to help with his care, which is why I’ve been absent Orchid of the month 2 from every CIOS meeting so far this year. You all probably think your current Notes and Tips president is a phantom! Book review Thus my topic: orchid care during vacations and other reasons that take us away from our collections. As summer and vacation season approach, it’s time to Contact Us consider ways to keep our orchids healthy when we’re not there to lavish care on www.ciorchidsociety.org them (because we ARE lavishing, right?). Join us on Facebook The first consideration is to ensure they get enough water during your absence. Central Illinois Orchid Orchids are resilient: they can go 10-14 days without being watered, assuming Society Newsletter is they’re watered thoroughly before you leave. The size of the pot and the growing published irregularly. Subscription is through medium, however, do affect how long the plant can go without water. Smaller membership in the plants need more frequent watering, and orchids growing in very coarse bark mix Society. will dry out sooner. -

Orchids for Everyone Mar 2013 Cattleyas.Pdf

Tuckers Orchid Nursery Presents… Orchids for Everyone Editor: Cathy Hine 1370 East Coast Road. Redvale, Auckland, NZ. Ph (09) 473 8629 Website: www.tuckersorchidnursery.co.nz Issue 26: March 2013 FROM ROSS THE BOSS Welcome back – This has been one of the hottest and driest summers I can remember for a few years. Your orchids will be smiling if you have been able to keep watering and feeding regularly. I was talking to a couple of commercial cymbidium growers, and they have noticed an increase in the number of flower spikes this year, because of last year’s poor light levels – too much cloud and raincover in summer, so they are predicting a tri-fecta pay out this year. Some are spiking from the bulbs that didn’t produce last summer. They have produced this year’s normal spiking, and an increase because of the high light levels and good temperatures – not too hot. If you don’t get a good flowering this year is not the weather conditions it’s your (the growers) fault. Not enough water and food. So get to it. It’s still not too late to produce spikes. Other genera have been similarly affected. Phalaenopsis have grown huge leaves because of the heat. Paphs have lots of new growths showing. Odontoglossums new larger bulbs and plenty of spikes showing, and cattleyas have lots of new growths and good flowering of the mature growths. I hope it continues along these lines throughout the year – and it truly will be a good Orchid Year. This month we feature Cattleyas as we have many new releases onto the web and lots of new cattleyas for the Orchid Club members. -

March - May 2002 REGISTRATIONS

NEW ORCHID HYBRIDS March - May 2002 REGISTRATIONS Supplied by the Royal Horticultural Society as International Cultivar Registration Authority for Orchid Hybrids NAME PARENTAGE REGISTERED BY (O/U = Originator unknown) AËRIDOVANDA Diane de Olazarra Aër. lawrenceae x V. Robert's Delight R.F. Orchids ANGULOCASTE Shimazaki Lyc. Concentration x Angcst. Olympus Kokusai(J.Shimazaki) ASCOCENDA Adkins Calm Sky Ascda. Meda Arnold x Ascda. Adkins Purple Sea Adkins Orch.(O/U) Adkins Purple Sea Ascda. Navy Blue x V. Varavuth Adkins Orch.(O/U) Gold Sparkler Ascda. Crownfox Sparkler x Ascda. Fuchs Gold R.F. Orchids Marty Brick V. lamellata x Ascda. Motes Mandarin Motes Mary Zick V. Doctor Anek x Ascda. Crownfox Inferno R.F. Orchids Mary's Friend Valerie Ascda. John De Biase x Ascda. Nopawan Motes Thai Classic V. Kultana Gold x Ascda. Fuchs Gold How Wai Ron(R.F.Orchids) BARDENDRUM Cosmo-Pixie Bard. Nanboh Pixy x Bark. skinneri Kokusai Pink Cloud Epi. centradenium x Bark. whartoniana Hoosier(Glicenstein/Hoosier) Risque Epi. Phillips Jesup x Bark. whartoniana Hoosier(Glicenstein/Hoosier) BRASSOCATTLEYA Ernesto Alavarce Bc. Pastoral x C. Nerto R.B.Cooke(R.Altenburg) Maidosa Bc. Maikai x B. nodosa S.Benjamin Nobile's Pink Pitch Bc. Pink Dinah x Bc. Orglade's Pink Paws S.Barani BRASSOLAELIOCATTLEYA Angel's Glory Bl. Morning Glory x C. Angelwalker H & R Beautiful Morning Bl. Morning Glory x Lc. Bonanza Queen H & R Castle Titanic Blc. Oconee x Lc. Florália's Triumph Orchidcastle Clearwater Gold Blc. Waikiki Gold x Blc. Yellow Peril R.B.Cooke(O/U) Copper Clad Lc. Lee Langford x Blc. -

Nomenclature

NOMENCLATURE The written language of Horticulture The Written Language of Horticulture To write the names of orchids correctly we must understand the differences between species and hybrids, know the abbreviations for the various species and hybrids and follow a few simple rules The Written Language of Horticulture 1. A species orchid occurs naturally in nature. Plants of the same species sometime vary in shape and colour. These are called varieties and given a special varietal name. 2. A hybrid is a cross between species or hybrids or a species and a hybrid. (A Primary hybrid is a cross between two species.) (A Natural hybrid is a cross that occurs naturally in nature.) The Written Language of Horticulture As an example we will look at the cattleya family species abbreviation Brassavola B. Cattleya C. Laelia L. Sophronitis Soph. Broughtonia Bro. The Written Language of Horticulture When a Cattleya is crossed with a Brassavola it becomes a Brassocattleya, abbreviated Bc. When a Cattleya and Laelia are crossed it becomes a Laeliocattleya, abbreviated Lc. When a Brassocattleya is crossed with a Laelia it becomes a Brassolaeliocattleya, abbreviated Blc. When a Brassolaeliocattleya is crossed with a Sophronitis it becomes a Potinara, abbreviated Pot. When a Broughtonia is crossed with a Cattleya it becomes a Cattletonia, abbreviated Ctna. The Written Language of Horticulture Why make these crosses 1. The Brassavola imparts large frilly labellums to the cross. 2. The Sophronitis imparts yellow, red, orange to the flowers. 3. The Broughtonia imparts dwarf structure, miniature clusters, good shape and flowers several times per year LET US NOW LOOK AT HOW TO WRITE THE NAMES OF ORCHIDS The following are a few rules that will assist in writing orchid names. -

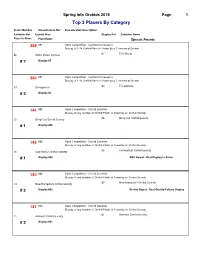

COS 2019 Show Ribbon Awards by Class

Spring Into Orchids 2019 Page 1 Top 3 Placers By Category Ticket Number Classification Ref Classification Description Exhibitor Ref Exhibit Area Display Ref Exhibitor Name Place In Class Plant Name Special Awards 359 001 Open Competition - Commercial Growers Display of 1-24 Orchid Plants in flower by a Commercial Grower 07 Eric Wang 06 White Plains Orchids # 2 Display #7 360 001 Open Competition - Commercial Growers Display of 1-24 Orchid Plants in flower by a Commercial Grower 03 Ecuagenera 37 Ecuagenera # 3 Display #3 144 003 Open Competition - Orchid Societies Display of any number of Orchid Plants in flower by an Orchid Society 06 Deep Cut Orchid Society 15 Deep Cut Orchid Society # 1 Display #06 145 003 Open Competition - Orchid Societies Display of any number of Orchid Plants in flower by an Orchid Society 08 Connecticut Orchid Society 16 Connecticut Orchid Society # 1 Display #08 AOS Award - Best Display in Show 140 003 Open Competition - Orchid Societies Display of any number of Orchid Plants in flower by an Orchid Society 05 New Hampshire Orchid Society 14 New Hampshire Orchid Society # 2 Display #05 Orchid Digest - Best Quality/Culture Display 141 003 Open Competition - Orchid Societies Display of any number of Orchid Plants in flower by an Orchid Society 01 Amherst Orchid Society 11 Amherst Orchid Society # 2 Display #01 Spring Into Orchids 2019 Page 2 Top 3 Placers By Category Ticket Number Classification Ref Classification Description Exhibitor Ref Exhibit Area Display Ref Exhibitor Name Place In Class Plant Name Special Awards 143 003 Open Competition - Orchid Societies Display of any number of Orchid Plants in flower by an Orchid Society 04 Cape & Islands Orchid Society 13 Cape & Islands Orchid Society # 2 Display #04 100 011 Cattleya Alliance(Laeliinae) Encyclia species 05 Chuck & Sue Andersen 10 New Hampshire Orchid Society # 1 Encyclia vitellina 67 011 Cattleya Alliance(Laeliinae) Encyclia species 07 Eric Wang 06 White Plains Orchids # 2 Enc. -

Agriculture Dus Test Guidelines in Cattleya Orchids ABSTRACT

Research Paper Volume : 3 | Issue : 11 | November 2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Agriculture KEYWORDS : DUS, cattleya, descrip- Dus Test Guidelines in Cattleya orchids tors, hybrids, varieties L.C. De NRC for Orchids, Sikkim Centre for Orchid Gene Conservation of Eastern Himalayan Region, Senapati District, A.N. Rao Manipur State Ex-Professor, Department of Pomology and Floriculture, College of Horticulture, Kerala P.K. Rajeevan Agricultural University, Vellanikkara, Trichur S. R. Dhiman Floriculturist, Y.S. Parmer University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, Solan Manoj Srivastava PPV & FRA, NASC Complex, New Delhi R.P. Medhi NRC for Orchids, Sikkim Geetamani Chhetri NRC for Orchids, Sikkim ABSTRACT According to UPOV Convention 1961, DUS (Distinctiveness, Uniformity and Stability) testing is useful system for protection of varieties, for evolving of new genotypes of plants and for the utility of breeders and farmers. It provides rights for breeders and farmers to exploit or develop new plant varieties, to allow access to foreign varieties with widen gene pool, to promote intensive breeding activities and to prevent unauthorized varieties exploitations. In the present study, 8 hybrids of Cattleya were evaluated for development of DUS test guidelines using common descriptors. Out of 53 com- mon descriptors developed, plant height, leaf number/ pseudobulb, flower width in front view, petal predominant colour, lip predominant colour and lip colour pattern were used for grouping of hybrids. Introduction Centre) with at least two shoots wereselected for DUS testing. Orchids belong to family Orchidaceae, one of the largest family Usually, healthy and insect pest and disease free plants are re- of flowering plants with both terrestrial and epiphytic members quired for testing for taking morphological observations without (Karasawa, 1996). -

January 2017

The Atlanta Orchid Society Bulletin The Atlanta Orchid Society is affiliated with the American Orchid Society, the Orchid Digest Corporation and the Mid-America Orchid Congress Newsletter Editors: Mark Reinke & Valorie Boyer www.AtlantaOrchidSociety.org January, 2017 Volume 63: Number 1 JANUARY MONTHLY MEETING Monday, January 9, 2017 Atlanta Botanical Garden Day Hall - 8pm Speaker: Jason Ligon Atlanta Botanical Garden Orchid Center Assistant Horticulturist (864)378-5792 cell [email protected] “Baby Steps For The Orchid Seedling Program” Jason Ligon has a background in eld research and horticulture. The annual swearing in of oces at the December 2016 meeting. While earning his B.S. in conservation biology from Clemson University, he mapped him the privilege to serve such In This Issue invasive plants for the National clients as the Loews Hotel, Ted Park Service at Fire Island Turner, and Tyler Perry Studios. 2 ATLOS Volunteer Listing National Seashore. He also 3 Events Calendar & studied abroad and worked on Jason volunteered at ABG for 3 President’s Message the island of Bioko in Equatorial years in outdoor horticulture and Guinea. While there he the tissue culture lab before 4 Minutes from the previous contributed to research making the jump to assistant Meeting concerning indigenous primates horticulturist for the orchid 4 Monthly Ribbon and orchids. center in 2014. Now he has the Winners opportunity to oversee the Before coming on board as the Madagascan orchid collection 10 Orchid Highlights assistant horticulturist for the and maturing seedlings from the orchid center, Jason worked in tissue culture lab among other 11 Recent AOS Awards from the Atlanta Judging Center interior scaping with Avant responsibilities. -

Aeridovanda Angulocaste Aranda Ascocenda

NEW ORCHID HYBRIDS January – March 2003 REGISTRATIONS Supplied by the Royal Horticultural Society as International Cultivar Registration Authority for Orchid Hybrids NAME PARENTAGE REGISTERED BY (O/U = Originator unknown) AERIDOVANDA Akia Akiikii Aer. lawrenceae x V. Antonio Real A.Buckman(T.Kosaki) Eric Hayes Aer. vandarum x V. Miss Joaquim W.Morris(Hayes) ANGULOCASTE Sander Hope Angcst. Paul Sander x Lyc. Jackpot T.Goshima ARANDA Ossea 75th Anniversary Aranda City of Singapore x V. Pikul Orch.Soc.S.E.A.(Koh Keng Hoe) ASCOCENDA Andy Boros Ascda. Copper Pure x Ascda. Yip Sum Wah R.F.Orchids Bay Sunset Ascda. Su-Fun Beauty x Ascda. Yip Sum Wah T.Bade Denver Deva Nina V. Denver Deva x Ascda. Yip Sum Wah N.Brisnehan(R.T.Fukumura) Fran Boros Ascda. Fuchs Port Royal x V. Doctor Anek R.F.Orchids Kultana Ascda. Jiraprapa x V. coerulea Kultana Peggy Augustus V. Adisak x Ascda. Fuchs Harvest Moon R.F.Orchids Viewbank Ascda. Meda Arnold x Ascda. Viboon W.Mather(O/U) BARKERIA Anja Bark. Doris Hunt x Bark. palmeri R.Schafflützel Gertrud Bark. dorothea x Bark. naevosa R.Schafflützel Hans-Jorg Jung Bark. uniflora x Bark. spectabilis R.Schafflützel Jan de Maaker Bark. skinneri x Bark. naevosa R.Schafflützel Remo Bark. naevosa x Bark. strophinx R.Schafflützel Robert Marsh Bark. uniflora x Bark. barkeriola R.Schafflützel BRASSAVOLA Memoria Coach Blackmore B. [Rl.] digbyana x B. Aristocrat S.Blackmore(Ruben Sauleda) BRASSOCATTLEYA Akia Nocturne C. Korat Spots x B. nodosa A.Buckman(O/U) Carnival Kids B. nodosa x C. [Lc.] dormaniana Suwada Orch. -

SOOS November 2019

SOUTHERN ONTARIO ORCHID SOCIETY November 2019, Volume 54, Issue 10 Meeting since 1965 Next Meeting Sunday, November 3, Floral Hall of the Toronto Botanical Garden. Vendor sales noon to 1pm. Noon, Culture talks on the stage by Alexsi Antanaitis. Topic ? Program at 1pm Our guest speaker George Hatfield, owner and operator of Hatfield Orchids in, Oxnard, CA will speak on Cymbidiums. George is an AOS and Cymbidium Society judge and a hybridizer. Monthly show table. Bring your flowering plants for show and tell and points towards our annual awards. Raffle President’s Remarks Welcome Orchid Enthusiasts. Fall has come, although as I write this in mid-October, the temperatures in my area have Don will be on the lookout for plants, so please help not yet neared freezing, so my plants are still him out by sending some of your plants on a road outdoors. The cool nights are helping set buds on trip to Southwestern Ontario. They may even come my Phalaenopsis, and helping to “harden off” the back with some awards. summer growths of my Cattleyas, which should lead to a bountiful display of blooms over the next Thank you in advance for those members who few months. I’ve already moved a few plants with generously lend their precious plants. The SOOS buds indoors under lights, in order to speed up the displays could not happen without you. opening of the blooms. The rest of my plants will come indoors over the next 2 weeks (or faster if the Our future meetings for the remainder of this year are as weather necessitates, i.e frost warnings). -

1 Green: Plant Research

Morning Song C Melody Fair x Morning Glory Ojai 'Verte' HCCODC Bc Pervenusta x Lc luminosa Orange Imp ‘Kaaawa’ Lc Trick or Treat x B digbyana GREEN: PLANT RESEARCH Owen Holmes ‘Mendenhall’ AMAOS Harlequin x Oconee Ports of Paradise ‘Emeral Isle’ FCCAOS Fortune x B digbyana P O BOX 597, KAAAWA, HAWAII 96730 U S A --‘Glenyrie’s Green Giant’ FCCAOS TELEPHONE/FAX 1 (808) 237-8672 Ronald Hauserman x Myrtle Beach E-MAIL [email protected] Rugley’s Mill ‘Mendenhall’ HCCAOS Sc Autumn Symphony x Oconee Web Site www.Rare-Hoyas.com Tokyo Magic x B digbyana Toshie Aoki ‘Pizzaz’ AMAOS Faye Miyamoto x Waianae Flare Toshie’s Magic Lc Tokyo Magic x Toshie Aoki ORCHID LIST Volcano Blue ‘ Kaaawa’ ‘coerulea’ Lois McNeil x Lc Blue Boy OCTOBER 2013 Whiporee 'Unbelieveable' Bc Deesse x Ranger Six If you have any Spathoglottis, Sobralia, Blue Catts, Calanthe or Phaius that you don't see on this BRASSAVOLA list please let me know - maybe we can do some horse trading, buying, stealing? cordata “H & R” species digbyana 'Mrs. Chase' AMAOS species AERANTHES --‘Seafoam Beauty’ species grandiflora species glauca xxxx H&R species Little Stars nodosa x cordata ASCOCENTRUM nodosa ‘Susan Fuchs FCCAOS species miniatum species --'Puerto Rico' species BLETIA BULBOPHYLLUM catenulata species cladestinum ‘Elizabeth’ species patula species Koolau Starburst lobii x levanae Wilmar Galaxy Star dearie x lobbii BRASSIA Edvah Goo longissima x giroudiana BROUGHTONIA sanguinea Yellow Star species BRASSOCATTLEYA (Brassavola x Cattleya) Bride's Blush 'Kaaawa' C claesiana x speciosa CADETIA Bride’s Rouge ‘Kaaawa’ Bride’s Blush x speciosa taylori species Green Dragoon 'Lenette' AMAOS Harriet Moseley x C bicolor Maikai ‘Spotted Star’ B nodosa x C. -

2018 Dos Auction Information

2018 DOS AUCTION INFORMATION Name and/or cross parentage Blooming Size Color Aerides odorata H BS AOS Bulletin Collection of A. Chadwick articles - Bag ½ cu ft med charcoal - Bag ½ cu ft Rexius med bark - Bag 2 cu ft peat moss chunks - Bag 2 cu ft Redwood - Bag 20 liter Power Orchiata - Bag 20 liter Power+ Orchiata - Bag 40 liters Classic Orchiata - Bag 40 liters Power Orchiata - Beallara Patricia McCully 'Pacific Monarch' H in bloom purple (Dgmra. Winter Wonderland x Oda. Saint Wood) Box 1 cu ft sponge rock - Brassavola nodosa ('Mas Major' x 'Susan Fuchs') S 5" pot Brassia Rising Start 'Orchid Man' AM/AOS H sm division Brassocattleya Princess Teresa ‘Princess Michiko’ HCC-CCM/AOS H 7" pink bloom BS (Bc. Deesse X C. Old Whitey) Brassolaeliocattleya George King 'Serendipity' H BS division Brassolaeliocattleya Joe Walker 'Ray Mishima' H 7" pot Brassolaeliocattleya Keowee 'Mendenhall' H 8" pot Brassolaeliocattleya Maikap 'Mayum' H BS pink Brassolaeliocattleya Malworth 'Orchidglade (Lc Charlesworth X Malvern) H BS Bryobium (Eria) hyacinthioides S fragrant BS white clusters Bulbophyllum falcatum S BS brownish Bulbophyllum Frostii H BS Burrageara Irish Gold H in flower and bud yellow/brown Calanthe William Murray H in bloom Cattleya alliance hybrid (A) H BS Cattleya alliance hybrid (B) H BS Cattleya Chyong Guu Swan 'White Bowlder' (Wayndora x Persepolis) H BS white/purple lip Cattleya Dainty Pink (Lc. Sakura Sky x C. Horace 'Maxima' AM/AOS) H BS compact pink Cattleya Golden Shore H BS Cattleya intermedia 'VB' S in bloom purple Cattleya maxima S in sheath Cattleya Sunrise Chalet H BS Cattlianthe Blazing Sun (Kauai Starbright X Blazing Treat) H BS, small flower yellow Caulocattleya Chantilly Lace ‘Twinkle’ HCC/AOS H BS white, light stripes (C. -

February 2017 New Masdevallias You Can Grow by Tim Culbertson

President John Reyes Regular Meeting Schedule 1st Vice Pres. Janell Schuck Doors open at 6:30 pm 2nd Vice Pres. Open Table/chair setup, plants in place Secretary Marylyn Paulsen Ribbon judging starts at 7:00 pm Membership Wendy D'Amore Culture session Treasurer Elaine Murphy Speaker starts at 7:30 pm Auction Mong Noiboonsook Opportunity drawing Ribbon Judging Open Table/chair teardown Hospitality Maria Van Kooy Doors close at 9:30 pm Newsletter Russ Nichols Website Roberta Fox Library Open South Coast Orchid Society Newsletter Founded in 1950 February 2017 New Masdevallias You Can Grow by Tim Culbertson Monday, February 27, 2017 Program starts at 7:00 p.m. Although I teach middle school kids for a living, one of my passions has always been plants. I began growing orchids as an offshoot from working at Longwood Gardens in Philadephia just after college. I have an diverse collection of nearly 3000 Paphs, including awarded and select clones of historic importance. I also do a little hybridizing of my own, and growing up my own babies is a blast. I am the youngest accredited judge with the American Orchid Society, and have served in various capacities with different societies in California and on the East Coast. I love meeting other orchid people, and doing so often finds me traveling to shows, vendors, and peoples’ greenhouses to see the latest and greatest in new hybrids and to get the best orchid gossip. In addition to Longwood, I’ve worked at the Smithsonian Institution tending to their orchids, and for years for the United States National Arboretum, collecting rare plants and documenting cultivated species and hybrids for their herbarium.