Reinventing Loblaws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management's Discussion and Analysis

Management’s Discussion and Analysis Table of Contents 4 At a Glance The following Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) for George Weston 5 Our Business Limited (“GWL” or the “Company”) should be read in conjunction with the audited annual consolidated financial statements and the accompanying notes on pages 89 8 Key Performance Indicators to 171 of this Annual Report. The Company’s audited annual consolidated financial Operating Segments statements and the accompanying notes for the year ended December 31, 2019 have 12 Loblaw been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS” or “GAAP”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB”). 14 Choice Properties The audited annual consolidated financial statements include the accounts of 16 Weston Foods the Company and other entities that the Company controls and are reported in 19 Financial Results Canadian dollars, except where otherwise noted. 76 Outlook Under GAAP, certain expenses and income must be recognized that are not necessarily reflective of the Company’s underlying operating performance. Non-GAAP financial 77 Non-GAAP Financial Measures measures exclude the impact of certain items and are used internally when analyzing 87 Forward-Looking Statements consolidated and segment underlying operating performance. These non-GAAP 88 Additional Information financial measures are also helpful in assessing underlying operating performance on a consistent basis. See Section 14, “Non-GAAP Financial Measures”, of this MD&A for more information on the Company’s non-GAAP financial measures. The Company operates through its three reportable operating segments, Loblaw Companies Limited (“Loblaw”), Choice Properties Real Estate Investment Trust (“Choice Properties”) and Weston Foods. -

All In: Staying the Course on Our Commitment to Sustainability

All In: Staying the Course on Our Commitment to Sustainability Amazon Sustainability • June 2020 • sustainability.aboutamazon.co.uk Table of Contents Our World in 2020 3 About 5 Environment 16 People 47 Governance 68 Our World in 2020 WHILE THIS REPORT reflects our work throughout 2019, the world has clearly undergone a massive shift in 2020 with the emergence of COVID-19. We are, first and foremost, focused on the safety of our employees and contractors around the world. It is important that we help our customers through this difficult time, and Amazonians are working around the clock to get necessary supplies delivered directly to the doorsteps of people and organisations who need them. Our Whole Foods Market stores have remained open, providing fresh food and other vital goods for customers. AMAZON EMPLOYEES RECEIVE comprehensive health benefits starting on day one of employment. We are working on building scalable testing for coronavirus. We’ve distributed face masks and implemented temperature checks at sites around the world to help protect employees and support staff, and offer free masks to our Whole Foods Market customers. We regularly sanitise door handles, stairway handrails, lockers, lift buttons and touch screens, and disinfectant wipes and hand sanitiser are standard across our network. We have also introduced extensive social distancing measures to help protect our associates. In all, we have made over 150 significant process changes in our operations network and Whole Foods Market stores, which we audit frequently, to help teams stay healthy. DURING THIS CRISIS, we’ve added 175,000 new jobs to help meet customer demand for essential products. -

Nutrition in Our Aisles Featuring Guiding Stars

Nutrition In Our Aisles Featuring Guiding Stars Developed by Registered Dietitians Fun, FREE Field Trips at your local Atlantic Superstore® Now offering add-on Cooking Classes for $10 + taxes per participant (see back of flyer for locations) What is it? Hands-on nutritional Field Trips Led by Registered Dietitians through the aisles of the local grocery store (aprox 60 mins in length) Cooking Classes now available at $10 + taxes per participant Learn About • The benefits of choosing healthy foods • Guiding Stars food navigation system • Canada’s Food Guide and the importance of the four food groups • Helpful nutritional skills Why Attend? • Experiential learning is effective and fun The dietitian did an • Tours align with provincial Health Education curriculum amazing job speaking to the • Field Trips encourage activity in your local community children and keeping it on their level. I think they learned a lot; I know I did, just finding out Who is Eligible? about the 0 to 3 star ratings. I • Students in grades Junior Kindergarten to grade 8 hope I can bring my class back • Groups of 5 – 30 students again next year! • All non-school youth organizations (including camps, daycares, church groups etc.) Diane Cleveland, Alderney School, Dartmouth Nova Scotia To Book and Learn more: Call us at: www.FieldTripFactory.com 855.383.0900 Nova Scotia, PEI, New Brunswick Store Listings Field Trip + Cooking classes available at select locations. (Fee of $10 per participant + taxes will apply) For more information go to: www.fieldtripfactory.com/Cookingclass -

BMO Low Volatility Canadian Equity ETF (ZLB) Summary of Investment Portfolio • As at September 30, 2016

Quarterly portfolio disclosure BMO Low Volatility Canadian Equity ETF (ZLB) summary of investment portfolio • as at september 30, 2016 % of Net Asset % of Net Asset Portfolio Allocation Value Top 25 Holdings Value Financials ......................................................................25.4 Fairfax Financial Holdings Limited ............................................ 5.0 Consumer Staples .............................................................15.4 Dollarama Inc. ................................................................. 4.1 Real Estate ....................................................................12.0 Waste Connection, Inc. ........................................................ 3.7 Utilities ........................................................................11.7 Intact Financial Corporation ................................................... 3.6 Consumer Discretionary ......................................................10.3 Canadian REIT .................................................................. 3.6 Telecommunication Services .................................................. 8.1 BCE Inc. ......................................................................... 3.0 Information Technology ....................................................... 6.9 RioCan REIT ..................................................................... 2.9 Industrials ...................................................................... 3.7 Empire Company Limited, Class A ........................................... -

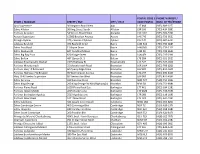

Loblaw Companies Stores Where Colleagues/Employees Are Mandated to Wear Masks

Loblaw Companies stores where colleagues/employees are mandated to wear masks Province Customers mandated to wear masks Effective December 9, the government of Alberta mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This includes all Alberta Loblaw stores in Alberta: Extra Foods, nofrills, Real Canadian Superstore, Real Canadian Liquorstore, Shoppers Drug Mart, T&T, Wholesale Club, Your Independent Grocer and Your Independent Liquorstore. Effective November 20, the government of British Columbia mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This British Columbia includes all Loblaw stores in British Columbia: City Market, Extra Foods, Joe Fresh, nofrills, Real Canadian Superstore, Shoppers Drug Mart, T&T, Wholesale Club and Your Independent Grocer. Effective November 12, the government of Manitoba mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This includes Manitoba all Loblaw stores in Manitoba: Extra Foods, nofrills, Real Canadian Superstore, Shoppers Drug Mart and Wholesale Club. Effective August 24, the government of Newfoundland mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This includes Newfoundland all Loblaw stores in Newfoundland: Dominion, nofrills, Shoppers Drug Mart, Your Independent Grocer and Wholesale Club. Effective October 9, the government of New Brunswick mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This New Brunswick includes all Loblaw stores in New Brunswick: Atlantic Superstore, nofrills, Shoppers Drug Mart, Your Independent Grocer and Wholesale Club. Effective July 31, the government of Nova Scotia mandates the use of masks in all indoor public spaces. This includes all Nova Scotia Loblaw stores in Nova Scotia: Atlantic Superstore, nofrills, Shoppers Drug Mart, Your Independent Grocer and Wholesale Club. -

A Participative Approach to Developing a Social Accounting and Planning Tool For

A Participative Approach to Developing a Social Accounting and Planning Tool for Cooperatives: The Consumer Co-operative Sustainability and Planning Scorecard1 André Leclerc, Leslie Brown, and Elizabeth Hicks with contributions from Monique Bourque, Roméo Cormier and Léo LeBlanc Introduction The Canadian retail grocery industry has been significantly transformed over recent decades. These changes have particularly impacted two aspects of the marketplace. First of all, companies owning grocery retail outlets are growing bigger, with much of the growth being the result of acquisitions and mergers rather than growth of existing firms. This has meant that smaller regional firms have been acquired, concentrating ownership and increasing the market share of the giant companies. For example, by 2002 three major food retailers – Loblaws, Sobeys and Metro – controlled 63 per cent of the Canadian market (Tutunjian 2002). Two of these firms, Sobeys and Loblaws, controlled 69 per cent of the Atlantic Canadian market. A second trend has involved expansion of the range of services offered, to include such items as: pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals 2 , banking services, clothing, gas, and so on. Further, other sectors, notably pharmacies and retail businesses such as Wal-Mart, provide groceries. According to the Retail Council of Canada (2003-2004), supermarkets are the most prominent example of such category incursion. Consumer tastes and concerns have evolved as well, to encompass concern for the health implications and quality of food, traceability of products, organics, and food labelling (Agriculture and Agri-food Canada 2005; Webb 2003). Complementing these concerns are others around the sustainability and environmental impacts of agricultural production and distribution practices (Agriculture and Agri-food Canada 2005). -

Global Powers of Retailing 2018: Canadian Executive Summary

Global powers of retailing 2018 Canadian executive summary Global powers of retailing 2018 | Canadian retailers in the top 250 This page has been intentionally left blank. 02 Global powers of retailing 2018 | Introduction Introduction Global powers of retailing is an annual report published by Deloitte that identifies the 250 largest retailers around the world based on publicly available data. This report is for the fiscal year 2016, which ended at June 2017. It analyzes retail performance across geographies and product sectors and highlights the most relevant retail trends. This year, the report also provides an outlook on the future of retailing through the lens of young consumers. 3 Global powers of retailing 2018 | Canadian retailers in the top 250 global retailers list Canadian retailers in the top 250 global retailers list There was limited change in the global rank of Canada’s largest retailers in 2017. The exception was Hudson’s Bay, which grew its retail revenue by 30 percent and jumped 27 spots in the global rank to #87. Hudson’s Bay’s growth was propelled by Within the grocery sector, three of the its recent acquisitions of GALERIA Kaufhof four Canadian retailers on the list declined and Gilt Groupe, and its organic growth, slightly in rank (Loblaw Companies Limited, through expansion into the Netherlands Metro Inc., and Overwaitea Food Group), and extension of Saks Fifth Avenue and while Empire Company Limited stayed Saks OFF 5TH into Canada. Its rapid growth steady at #53. qualified the company for the Fastest 50 list, which is based on compound annual revenue growth over the five-year period of 2010 to 2015. -

Growth Potential of Stocks: Security of a GIC

BMO Financial Group BMO Growth GIC Growth potential of Stocks: Security of a GIC This medium term GIC allows you to participate in the growth of Canadian stocks with no risk to your principal investment. It offers the potential to generate returns based on the performance of a basket of 15 large Canadian companies. Is this GIC right for you? Product Features This GIC may be right for you if you: Term • are looking to diversify your portfolio with a medium term investment Minimum Investment • would like principal protection Maximum Rate of Return • are willing to forego a guaranteed return for the potential for the Term to earn higher market linked returns • can keep your money invested until the end of the term 100 % Principal protected Reference Portfolio Key Benefits This GIC is an excellent way for you to gain access to the Company (equally weighted) returns on a portfolio of 15 large Canadian companies with • Toronto-Dominion Bank (The) (TD) • Royal Bank of Canada (RY) the security of principal protection. • Canadian Imperial Bank of • George Weston Limited (WN) Commerce (CM) • Principal protection 100% of your original investment is • Nutrien Ltd. (NTR) returned to you at maturity • Bank of Nova Scotia (The) (BNS) • Canadian Tire Corp Ltd (CTC.A) • BCE Inc. (BCE) • Higher return potential based on the performance of a • Suncor Energy Inc. (SU) portfolio of Canadian stocks • Saputo Inc. (SAP) • Enbridge Inc. (ENB) • Designed in partnership with BMO Capital Markets®, a • National Bank of Canada (NA) • TransCanada Corporation (TRP) market -

Congratulate Loblaw

July 22, 2015 Galen G. Weston President Loblaw Companies Limited 1 President’s Choice Circle Brampton, ON L6Y 5S5 Loblaw’s Promise to Eliminate Triclosan, Phthalates, and Microbeads from its Life Brand and President’s Choice Products by the end of 2018 Ottawa Riverkeeper would like to congratulate Loblaw Companies Limited on its recent announcement that it will eliminate triclosan, phthalates, and plastic microbeads from Life Brand and President’s Choice Products by the end of 2018. We are impressed and thankful to hear that Loblaws is taking further measures and has already begun to phase out products sold at your stores and that contain these ingredients that are toxic in the aquatic environment. You may be aware that Ottawa Riverkeeper was a signatory, along with more than 50 other public interest and not-for-profit groups from Canada and the United States, to a letter sent in late 2014, urging the Government of Canada to take urgent action to declare Triclosan to be toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) and to prohibit the use of Triclosan in consumer and institutional products. The Canadian government has stated that a risk management plan will be produced in the spring of 2015 yet we have heard nothing but silence. Almost 4 years ago experts assessed Triclosan and advised our federal government to add this chemical to the Toxics Substances List. Sadly, our government has ignored timelines and failed to act. We were also one of several environmental organizations that signed on to the request to the federal Minister of the Environment to prioritize the assessment of microbeads as “toxic” under CEPA. -

COVID-19 ‘You Are Not Alone’

COVID-19 ‘You Are Not Alone’ HEALTH CONCERNS – CALL TeleHealth and Local Public Health Units Contact Telehealth Ontario at 1-866-797-0000, your local public health unit or your primary care provider if you’re experiencing symptoms of the 2019 novel coronavirus. TORONTO – Public Health Hotline Call if you have questions about COVID-19 8:30 a.m. – 8 p.m. Telephone: 416-338-7600 TTY: 416-392-0658 Email: [email protected] 311 Toronto Outside City limits: 416-392-2489 Call if you have questions about City services. Telephone: 311 TTY: 416-338-0889 Emergency Services Telephone: 911 - Call if you’re having difficulty breathing or experiencing other severe symptoms. BRITISH COLUMBIA – HealthLink If you have health concerns, call HealthLink BC at 8-1-1. For non-medical information about COVID-19 Call 1-888-COVID19 (1-888-268-4319) or text 604-630-0300 from 7:30 am to 8 pm. ALBERTA – Health Link 811 Call Health Link 811 for additional advice. If you are not seriously ill, do not go to a physician’s office, a health care facility or a lab without consulting with Health Link 811 first. Call 911 if you are seriously ill and need immediate medical attention and inform them that you may have COVID-19 SASKATCHEWAN If you have no symptoms or exposure concerns, but have questions about COVID-19, you can: • Access the most up-to-date news and information on www.saskatchewan.ca/COVID19 • Email [email protected] Launch Self-Assessment - https://public.ehealthsask.ca/sites/COVID-19/ www.leslynlewis.ca COVID-19 ‘You Are Not Alone’ QUEBEC If you are worried about COVID 19 or display symptoms such as a cough or fever, you can call 418-644-4545 in the Québec City region, 514-644-4545 in the Montréal area, 450-644-4545 in the Montérégie region, 819-644-4545 in the Outaouais region and 1-877-644-4545 (toll free) elsewhere in Québec. -

Solid Foundations on Common Ground: Nevis' Multiform

Solid Foundations on Common Ground: Nevis’ Multiform Foundations Ordinance Jan Dash, Esq., L.E.C., TEP Liburd and Dash, Attorneys-at-Law www.LiburdDash.com [email protected] “Solid Foundations on Common Ground” © 2008 Jan Dash, Esq., L.E.C.,TEP. All rights reserved. For a free download of this article, please visit www.LiburdDash.com. Foundations. The legal entity known as a “foundation” has been a well- established vehicle in the civil law countries of Europe since the Middle Ages. The church, one of the most powerful institutions of the era, was frequently given assets by members of its congregation in an effort to further its beneficial mission. It was the goal of these ecclesiastical foundations to promote charitable, scientific and humanitarian objectives in accordance with the religious aims of the church. The societal conventions at the time believed that the church should be concerned solely with matters of faith and not that of asset management. As a result, legal theorists felt that any asset given to the church should have the ability to manage itself and should be classified as a legal person, separate and apart from the church. The uses of charitable foundations have evolved beyond the church and in recent years these entities have been established by affluent members of society to fulfill their philanthropic aims. The Alexander S. Onassis Foundation (the “Onassis Foundation”) was established by the late Aristotle Onassis in 1973 in the name of his predeceased son, to provide funds for education, literature, science and the promotion of Greek culture.1 The world’s wealthiest charity, Stichting INGKA Foundation (the “INGKA Foundation”), which is registered in Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles, owns 207 outlets of the multinational furniture store, IKEA. -

ITZ Loblaw Native Plant Store List 2021

POSTAL CODE / PHONE NUMBER / STORE / MAGASIN STREET / RUE CITY / VILLE CODE POSTAL NUM. DE TÉLÉPHONE Ajax Superstore 30 Kingston Road West Ajax L1T 4K8 (905) 683-2272 Zehrs Alliston 30 King Street South Alliston L9R 1H6 (705) 434-9391 Fortinos Ancaster 54 Wilson Street West Ancaster L9G 1N2 (905) 304-5740 Aurora Superstore 15900 Bayview Avenue Aurora L4G 7Y3 (905) 726-9532 Provigo Aylmer 375, chemin d'Aylmer Aylmer J9H 1A5 (819) 682-4433 Loblaws Bayfield 472 Bayfield Street Barrie L4M 5A2 (705) 735-6689 Zehrs Essa Road 11 Bryne Drive Barrie L4N 8V8 (705) 733-1119 Zehrs Duckworth 607 Cundles Rd East Barrie L4M 0J7 (705) 722-3636 Zehrs Big Bay Point 620 Yonge Street Barrie L4N 4E6 (705) 735-2390 Zehrs Bolton 487 Queen St. S Bolton L7E 2B4 (905) 951-9555 Loblaws Bowmanville Market 2375 Highway #2 Bowmanville L1C 5A3 (905) 623-2600 Fortinos Mountainash 55 Mountainash Road Brampton L6R 1W4 (905) 793-8200 Fortinos Hwy 10 & Bovaird 60 Quarry Edge Drive Brampton L6V 4K2 (905) 453-3600 Fortinos Highway 7 & Brisdale 35 Worthington Avenue Brampton L7A 2Y7 (905) 495-8108 Hwy 10 & Steeles Superstore 85 Steeles Ave West Brampton L6Y 0B5 (905) 451-4999 Zehrs Fairview 410 Fairview Drive Brantford N3R 7V7 (519) 754-4932 Zehrs King George 290 King George Rd Nth/Highway24 Brantford N3R 5L8 (519) 751-8988 Fortinos Plains Road 1059 Plains Road East Burlington L7T 4K1 (905) 634-1591 Fortinos Upper Middle 2025 Guelph Line Burlington L7P 4M8 (905) 336-6566 Fortinos Burlington Appleby 2515 Appleby Line Burlington L7R 0B6 (905) 319-1690 Fortinos New Street 5111 New Street Burlington L7L 1V2 (905) 631-7227 Zehrs Caledonia 322 Argyle Street South Caledonia N3W 1K8 (905) 765-8207 Zehrs Cambridge Centre 400 Conestoga Blvd Cambridge N1R 7L7 (519) 620-1376 Zehrs Hespeler 180 Holiday Inn Drive Cambridge N3C 3Z4 (519) 658-4689 Zehrs South Cambridge 200 Franklin Blvd Cambridge N1R 5S2 (519) 624-8170 Provigo Le Marché Charlesbourg 4545, boul.