Volume 9, No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wakefern's $16.5 Billion in Sales Sets Record

- Advertisement - Wakefern's $16.5 billion in sales sets record October 29, 2018 Wakefern Food Corp. reported record retail sales of $16.5 billion for the 52-week fiscal year ending Sept. 29, a 1.6 percent increase from the prior year. Wakefern opened four new ShopRite stores and two Price Rite Marketplace stores during the same period. “Thank you for believing that our way of doing business — a cooperative of family-owned businesses — can compete and win against the competition that comes our way,” Chairman and CEO Joseph S. Colalillo told an audience of nearly 900 people at the Hilton in East Brunswick, NJ. “The strong relationships we’ve created with our customers have built our brands and businesses.” 1 / 2 Colalillo also announced the retirement of Chuck Infusino, president of Little Falls ShopRite Supermarkets Inc., from Wakefern’s board of directors and the addition of Tom Cingari, a partner in Grade A Market, CT. “We thank Chuck for his service and commitment to the board. He will remain active in the cooperative and his own family company, which operates the ShopRite of Little Falls,” noted Colalillo. “We welcome Tom to the board and look forward to working with him and all the Board members to shape the course of our cooperative’s future.” President and COO Joe Sheridan recapped Wakefern’s accomplishments over the past year and noted future plans to open and remodel more stores in 2019 while expanding and enhancing e- commerce. He said Wakefern is actively testing artificial intelligence and next generation learnings to enhance the retail experience. -

FOOD CHOICE I Access to Healthy Food in Philadelphia

Running head: FOOD CHOICE i Access to Healthy Food in Philadelphia Neighborhoods: How Corner Stores Impact Food Choices Steve O’Connor Master of Science Degree Candidate Science, Technology, and Society Department of History & Politics Drexel University Thesis Adviser: Professor Christian Hunold March 2013 _______________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Drexel University Department of History & Politics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science ________________________________________________________________________ FOOD CHOICE ii Acknowledgements Thank you to all of my professors and classmates in the Science, Technology, and Society program for providing a wonderful learning experience over the last two years. I am also extremely thankful to everyone I have had the pleasure to work alongside or get to know through my experiences, and to the participants who agreed to be a part of this study. To my thesis adviser Professor Christian Hunold, I greatly appreciate all of your help and encouragement throughout this process. Thank you for introducing me to the wonderful world of research and challenging and inspiring me. I’d also like to thank Jen Britton and Katy Travaline for all of your advice, support, listening, and most importantly, introducing me to the STS program. Finally, thank you to my family and friends, with special thanks to Kelly, my wonderful wife. Thank you for all your patience, proofreading, and the tremendous amount of support you have given me over the last few years. I am grateful. FOOD CHOICE iii Abstract Over the last fifteen years, access to fresh and nutritious food has been recognized as a growing problem within the United States, specifically in low-income, urban neighborhoods. -

New Jersey to Launch Online Grocery Shopping for SNAP Recipients Amazon, Walmart, Shoprites & the Fresh Grocers to Accept SNAP Online Orders May 20, 2020

New Jersey to Launch Online Grocery Shopping for SNAP Recipients Amazon, Walmart, ShopRites & The Fresh Grocers to Accept SNAP Online Orders May 20, 2020 (TRENTON) – New Jerseyans enrolled in the state’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) will be able to use their benefits to order groceries online starting next week. Online shopping will be available through Amazon and participating Walmarts, ShopRites and The Fresh Grocers. NJ SNAP recipients will be able to use their benefits card to order groceries from Amazon starting on May 27. Walmarts, ShopRites and The Fresh Grocers that that provide online shopping will also accept online ordering with SNAP benefits starting on May 28. “Online grocery shopping is another important step in our efforts to get affordable groceries to New Jerseyans during this public health emergency,” Human Services Commissioner Carole Johnson said. “Having the option to order groceries online is more important than ever, as we all work together to stay-at-home as much as possible. We hope that the launch of SNAP online grocery shopping promotes equity by providing participants access to a convenient tool that many New Jerseyans are already using to comply with the stay-at-home order.” NJ SNAP currently serves about 700,000 New Jerseyans in 356,000 households, with the monthly SNAP benefit based on household size and income. Recipients will be able to use their Families First Electronic Benefits Transfer card to purchase eligible groceries from the participating retailers. Under federal rules, SNAP benefits cannot be used to pay for delivery fees. To learn more, recipients can visit Amazon.com/SNAP to register their EBT card. -

August 22, 2018 the Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary

August 22, 2018 The Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary U.S. Department of the Treasury 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20220 Dear Secretary Mnuchin: The undersigned organizations urge the Treasury Department to issue interim guidance with respect to drafting errors that were made to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“Act”) -- provisions dealing with qualified improvement property (“QIP”) and net operating losses (“NOL”). The signatories to this letter may have an interest in one but not necessarily both of the provisions but recognize the need to have them both resolved on an expeditious basis. The delay in correcting these provisions has caused economic hardship for some retailers, restaurants, members of the real estate industry, and suppliers of building products, and is also delaying investments across the economy that impact the communities in which these companies are doing business. This also results in safety concerns because, in some cases, it is causing a delay in upgrading existing sprinkler systems, creating a more perilous situation for our nation’s firefighters. At the outset, it is important to note that it is widely acknowledged that both the QIP and NOL provisions contain unintended drafting errors such that the provisions do not currently operate consistent with Congressional intent – there are no policy or technical objections suggesting that these drafting errors should not be corrected. The drafting error in the QIP provision causes improvements to buildings to be written off over 39 years instead of one year as contemplated under the Act. As a result, a taxpayer gets to write off only 2.5% of their improvement costs in the year the expenditures are made, and 97.5% over the remaining 38 years, instead of writing off 100% of the cost in the year the expenditures are made. -

Wakefern Food Corp. Clarifies Member Acquisition of Two New Locations Village Super Market Inc

FOR INFORMATION CONTACT: Karen Meleta Wakefern Food Corp./ShopRite (732) 906-5363 [email protected] Wakefern Food Corp. Clarifies Member Acquisition of Two New Locations Village Super Market Inc. Bids on Two Superfresh stores in Baltimore, MD Keasbey, NJ, May 26, 2011 - Recent media reports have identified ShopRite® as the winning bidder of 10 Superfresh locations in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan area. Wakefern Food Corp., owner of the ShopRite trademark, announced today that it seeks to clarify those reports in an effort to correct any misinformation reported by the media. “As a cooperative with 47 members who own and operate their own stores under the ShopRite banner, our membership frequently identifies new possible ShopRite locations,” stated Karen Meleta, vice president of Consumer and Corporate Communications. “In this case, one of our members, Village Super Market, Inc., was part of a bidding group that successfully bid on 10 Superfresh stores in the Maryland market as part of the A&P bankruptcy reorganization.” Of the 10 stores included in the bid, two stores -- White Oak and Timonium -- have been identified by Village Super Market, Inc. as locations it would operate as ShopRites. The bid is subject to bankruptcy court approval and other conditions and the closing is expected in approximately one month. Wakefern has not bid on or entered into any agreement with another retailer or other party to bid upon or purchase any Superfresh locations. ### About Wakefern Food Corp. From a small, struggling cooperative with eight members – all owners of their own grocery stores – Wakefern Food Corp. has grown into the largest retailer-owned cooperative in the United States. -

Ii K. C. Mirror to Big Packer Woes

-487 0 .398 4Ss `21: -95 -53s o tn .340 0 -53s o 21, -540 o 22 .885--o4 -920 o -97s o 21 -92s 0 24 14th year no. 18 445 0 July 2, 1968 19 1345 0 1 1345 0 1030 0 1 1300 1 155 0 K. C. Mirror To Big Packer Woes 11 -977 o The meat packing industry is ductivity. The old-line meat line packing plant in Salt Lake -935 o City and reduced operations in 12 celebrating its centennial in 'packers awoke one day to find 1000 0 17 Kansas City, Kansas, by dying athemselves outclassedin Omaha. It will concentrate on -920 o the 17, little more. the more profitable areas of 1155(@ field they had dominated for 1/ It's just one more turn of the the business and expand such -915 o so long. 11, wheel in a quiet revolution with- nonmeat operations as salt min- -945 0 In 1950, the four largest meat 16, in one of the nation's largest ing, animal feeds and pharma- -770 0 4 packers accounted for more and most volatile businesses. than 51 per cent of the nation's ceuticals. -765 0 The sprawling old meat pack- George A. Hormel & Co. plans -815 0 I federally inspected cattle slaugh- ing plants, once virtual trade- ter and 38 per cent of total com- to spend 15 million for capital @2 marks of Kansas City and othermercial slaughter. By 1962 theiradditions and improvements @ 2 Mid -Western rail centers, have share of the business had drop- this year. -

THE FRESH GROCER® to JOIN WAKEFERN COOPERATIVE Philadelphia-Based Retailer Will Be 50Th Cooperative Member

FOR INFORMATION CONTACT: Santina Stankevich Wakefern Food Corp./ShopRite (732) 906-5932 [email protected] THE FRESH GROCER® TO JOIN WAKEFERN COOPERATIVE Philadelphia-based retailer will be 50th cooperative member Keasbey, NJ (July 31, 2013) – Wakefern Food Corp. announced today that The Fresh Grocer® will join the cooperative effective October 1, 2013. Based in Philadelphia, The Fresh Grocer, which will continue to be owned and operated by Patrick J. Burns, consists of eight stores – six in the Philadelphia-area, as well as one in Wilmington, DE and one in New Brunswick, NJ. Upon joining Wakefern, one Philadelphia-area location will transition to the ShopRite banner while the remaining seven locations will remain The Fresh Grocer stores. Wakefern will now own the The Fresh Grocer trademark. “Adding the strength of The Fresh Grocer brand and its unique offering will help us to continue our growth in the Philadelphia marketplace,” said Joe Sheridan, Wakefern president & COO. “With several stores strategically located near college campuses, The Fresh Grocer will give us new insight into the next generation of consumers and will expand our reach to a new customer, while providing them with a wide offering of ShopRite branded products.” “As the 50th member of the Wakefern cooperative, Pat Burns and his team embody the spirit of entrepreneurship that Wakefern was built upon,” said Joseph S. Colalillo, chairman and CEO of Wakefern Food Corp. “Like our ShopRite and PriceRite stores, The Fresh Grocer shares our passion for customer service; focus on freshness and commitment to giving back to the community. We are delighted to welcome them to the Wakefern family.” “Joining the Wakefern team will be strategically beneficial to our customers, associates and company as a whole,” said Patrick J. -

Rite Stores, 56 Price Rite Stores and Six the Fresh Grocer Stores 18

POWERX Top Pharmacy Retailers 46 • APRIL 27, 2015 DRUGSTORENEWS.COM FOOTNOTES FOR TOP PHARMACY RETAILERS 1. Includes only retail pharmacies and specialty pharmacies Profiles of leading 2. Based on retail sales 3. Includes pharmacy services segment revenue of $88.4 billion and retail sales of $67.8 billion 4. Retail stores pharmacy retailers 5. Fiscal year 2015 for the 52 weeks ended Feb. 28 6. As of Feb. 28, not including 647 Sam’s Club stores. Total includes 3,407 supercenters, 470 discount stores, 603 Neighborhood Markets and 40 smaller-format units With more than $225 billion in pharmacy sales 7. DSN estimates for independent network sales 8. Excluding Medicine Shoppe and Medicap stores and more than 67,000 stores, the 2015 PoweRx 9. Includes results from Shoppers Drug Mart and Loblaw pharmacy locations 10. Includes total Loblaw sales plus Shoppers Drug Mart revenues 11. 2014 sales are lower due to fewer stores (had to sell about 300 stores to complete list represents more than 80% of the total retail merger) 12. Diplomat operates nine regional fill centers pharmacy business. And with the implementation 13. U.S. stores only, including Medicine Shoppe and Medicap pharmacies 14. U.S. operations of the Affordable Care Act, they are creating 15. Projected for fiscal year ended March 1, 2015 16. Including in-store pharmacies, offsite clinics, specialty pharmacy and central-fill center innovative programs and entering healthcare 17. 256 ShopRite stores, 56 Price Rite stores and six The Fresh Grocer stores 18. Excludes Save-A-Lot and supply chain sales; projected for fiscal year 2015 partnerships to move beyond dispensing and 19. -

NGA Retail Membership List by State – Winter 2019

NGA Retail Membership List by State – Winter 2019 Company City State A & R Super Markets, Inc. Calera Alabama Autry Greer & Sons Inc Mobile Alabama Baker Foods, Inc. Pell City Alabama Bruce Management, Inc. Fort Payne Alabama Farmers IGA Foodliner Opp Alabama Food Giant, Inc. Bessemer Alabama Forster & Howell Inc Dothan Alabama Fourth Avenue Supermarket Bessemer Alabama Freeman's Shur-Valu Foods Dothan Alabama Fuller's Supermarket Greensboro Alabama Gateway Foodland Inc Double Spgs Alabama Gregerson's Foods, Inc. HQ Gadsden Alabama Holley Oil Company Wetumpka Alabama Johnson's Giant Food, Inc. Attalla Alabama Piggly Wiggly Warrior Alabama Pinnacle Foods dba Save A Lot Mobile Alabama Ragland Bros Retail Co's, Inc. Huntsville Alabama Renfroe, Inc. Montgomery Alabama Star Super Market, Inc. Huntsville Alabama Tallassee Super Foods Tallassee Alabama Western Supermarkets, Inc Birmingham Alabama Wright's Markets, Inc. Opelika Alabama Benjamin's IGA Wrangell Alaska City Market, Inc. Wrangell Alaska Copper Valley IGA Glennallen Alaska Country Foods IGA Kenai Alaska Cubbys Marketplace IGA Talkeetna Alaska Fairway Market IGA Skagway Alaska Hames Corporation Sitka Alaska Howsers IGA Supermarket Haines Alaska IGA Food Cache Delta Junction Alaska Tatsudas IGA Ketchikan Alaska Trading Union IGA Market Petersburg Alaska Freson Bros. Stony Plain Alberta Rodney's Supermarket Arima Arima Del Sol IGA #6 San Luis Arizona Ed's IGA Market Snowflake Arizona El Rancho Market IGA Chandler Arizona Food Town IGA Eloy Arizona Garrett's IGA Supermarket Rio Rico Arizona Norms IGA Kearny Arizona Olsens IGA Market Yuma Arizona RCCM Foodtown IGA Market Eloy Arizona Shopes Market IGA Coolidge Arizona The Butcher & The Farmer Marketplace IGA Buckeye Arizona Tonto Basin Market Place IGA Tonto Basin Arizona Wilburs IGA Market Saint Johns Arizona Cranford's Fresh World Little Rock Arkansas Cranford's Fresh World dba FoodWise Hot Springs Village White Hall Arkansas Cranford's Fresh World dba ShopWise Redfield Redfield Arkansas Cranford's Fresh World, Rison Rison Arkansas Dale Newman Management Co. -

The Food Industry Scorecard

THE FOOD INDUSTRY SCORECARD An evaluation of food companies’ progress making—and keeping— animal welfare promises humanesociety.org/scorecard Executive summary Most of the largest U.S. food companies have publicly pledged to eliminate certain animal abuses from their supply chains. But as countless consumers have asked: are they keeping their promises? For context, the vast majority of animals in our food system live Here’s the good news: that kind of radical view is out of in dismal conditions. Mother pigs are locked in gestation crates step with traditional American values. Agribusiness may see ani- so small they can’t turn around. Egg-laying hens are crammed mals as mere machines, but consumers don’t. into cages so tightly they can’t even spread their wings. And chickens in the poultry industry are bred to grow so large, so ɠ As the American Farm Bureau reports, nearly all consumers (95%) believe farm animals should be fast they suffer from agonizing leg disorders. treated well. It wasn’t always this way. Throughout history, animals hav- en’t been forced to endure such miserable lives. (And today, ɠ The Food Marketing Institute found that animal welfare is shoppers’ second most important social issue. there are certainly farmers who don’t use these abusive prac- tices.) But as agri-culture developed into agri-business, the ɠ The food industry analytics firm Technomic concluded industry’s relationship to animals became more severe. that for American restaurant patrons, concerns about animal cruelty outweigh those regarding the “Forget the pig is an animal,” urged Hog Farm Management environment, fair trade, local sourcing and other issues. -

(NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Guides, Handbooks and Manuals Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection 1972 National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), "National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File" (1972). Guides, Handbooks and Manuals. 703. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides/703 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides, Handbooks and Manuals by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NATIONAL AUTOMATED ACCOUNTING RESEARCH SYSTEM NAARS OFFICIAL LISTING OF THE CORPORATIONS COMPRISING THE 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE PAGE 1 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE ALPHABETICAL LISTING COMPANY NAME SIC S EX B S DATE AUDITOR A & E PLASTIK PAK CO., INC. 309 ASE 12-31-72 PMM A.B. DICK COMPANY 508 OTC 12-31-72 AA A.E. STALEY MANUFACTURING COMPANY 204 NySE 09-30-72 HS a.g. Edwards & sons inc 621 ASE 02-28-73 TR a.h. rOBins company, incorporated 283 NYSE 12-31-72 a.m. pullen & company a.M. castle & co. 509 ASE 12-31-72 AA a.o. smith corporation 371 NYSE 12-31-72 ay a.p.s. -

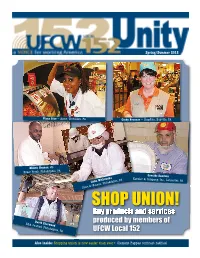

Spring/Summer 2012 Unity

Spring/Summer 2012 Ulana Rice — Acme, Glenolden, PA Cindy Brenner — ShopRite, Bayville, PA Milton Haynes, Jr. Super Fresh, Philadelphia, PA Osvaldo Sanchez wska Kunzler Witko , PA & Company, Inc., Lancaster, PA Lidia delphia n, Phila Watso Dietz & SHOP UNION! Buy products and services Dav produced by members of B& id Sher A Seaf wood ood, Ph iladelp hia, PA UFCW Local 152 1 Spring/SummerA 2l0s1o2 inside: Shopping union is now easier than ever • Clement Pappas contract ratified Flu season 2012-2013 Buy American! he United States Food and Drug workplace, check the van schedule in Visit Administration (FDA) has re - the fall edition of the UFCW’s In commended three flu viruses for Touch or visit UFCW Local 152’s web - americansworking.com T inclusion in the 2012-2013 sea - site at www.ufcwlocal152.org . sonal flu vaccine, based on recommen - Who should be vaccinated? for information on finding dations from the World Health Everyone over the age of 6 months American-made products. Organization (WHO). The WHO advised inclusion of vac - should get vaccinated every year. Support U.S. workers cines for the following three viruses: Immunity to an influenza virus and help save jobs. declines over time and may be too low • an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-pdm to provide protection after a year. 09-like virus; It takes about two weeks after vacci - • an A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2)-like nation for antibodies to develop and virus, and provide protection. In the meantime, • a B/Wisconsin/1/2010-like virus you are still at risk for getting the flu.