Regional Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the James River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the James River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1008 Geology and Mineral ·Deposits oftheJatnes River-Roanoke River Manganese District Virginia By GILBERT H. ESPENSHADE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1008 A description of the geology anq mineral deposits, particularly manganese, of the James River-Roanoke River district UNITED STAT.ES GOVERNMENT, PRINTING. OFFICE• WASHINGTON : 1954 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS· Page Abstract---------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction______________________________________________________ 4 Location, accessibility, and culture_______________________________ 4 Topography, climate, and vegetation _______________ .,.. _______ ---___ 6 Field work and acknowledgments________________________________ 6 Previouswork_________________________________________________ 8 GeneralgeologY--------------------------------------------------- 9 Principal features ____________________________ -- __________ ---___ 9 Metamorphic rocks____________________________________________ 11 Generalstatement_________________________________________ 11 Lynchburg gneiss and associated igneous rocks________________ 12 Evington groUP------------------------------------------- 14 Candler formation_____________________________________ 14 Archer Creek formation________________________________ -

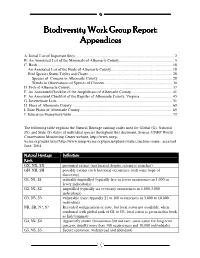

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Nelson County, Virginia

At Risk Nelson County, Virginia FERC Presentation Dec. 15, 2014 REF: Atlantic Coast Natural Gas Pipeline proposed by Dominion/Duke Energy DOCKET NUMBER: PF 15-6 Route of Proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline in Virginia Nelson County At Risk: Nelson’s Rural Character & Heritage ▪ Proud, longstanding and protected rural heritage dating to late 1600’s ▪ Pipeline Route Threatens Agricultural and Tourism Enterprises ▪ Pipeline Disrupts Low Impact Tourism- Based Economy (resort, inns, wineries, breweries) reliant on unspoiled view sheds ▪ Pipeline Threatens Native American Archaeological Sites, African-American Slave Cemeteries ▪ Pipeline Route Introduces Industrial Usage in Agricultural Zones At Risk: Nelson’s Economy ▪ Agricultural and tourist-based economy relies on Nelson “brand” being maintained ▪ Brand dependent on reputation of Nelson’s unscarred mountain vistas, non-fragmented forests, fertile fields and clear mountain streams ▪ Pipeline crosses and blights the fastest growing tourist- related business area in the County ▪ Pipeline construction havoc will clog County’s main traffic arteries, most of which are narrow two-lane roads, and discourage tourism ▪ Once brand tarnished, almost impossible to restore with presence of invasive infrastructure ACP ROUTE-- NELSON COUNTY o Thirty-five miles, 531 acres for ROWs o Devalues 225 private properties o Harms small locally owned businesses o Does not take advantage of existing Rights of Way (ROW) o Traverses unique physiography— o Steep mountainous slopes o Unstable soils o Susceptible to significant -

Capital Outlay

Capital Outlay Proposed Capital Outlay Funding HB/SB 30 Fund Type 2016-18 General Fund $151.3 VPBA/VCBA Tax-Supported Bonds 2,261.1 9(c) Revenue Bonds 14.4 9(d) NGF Revenue Bonds 211.2 Nongeneral Fund Cash 281.1 Total $2,919.1 The Governor’s proposed capital outlay budget for the FY 2016-18 biennium totals $2.9 billion from all funds. • Projects Proposed to be Supported with General Fund Cash Include: Proposed GF Supported Projects ($ in millions) Agency Project GF Ag. & Consumer Services Install Generators in Reg. Labs $0.8 Virginia State Ext. Replace HVAC in Carter Bldg. 1.0 Gunston Hall Construct New Water Lines 0.2 Central Capital Outlay Maintenance Reserve 129.4 Central Capital Outlay Capital Project Planning 20.0 Total, GF Cash Supported Capital Projects $151.3 133 • Descriptions of the General Fund Supported Projects are Set Out Below: − Agriculture and Consumer Services. Proposes $750,000 GF in FY 2017 for the installation of generators in regional laboratories. − Virginia State Extension. Recommends $950,000 GF in FY 2017 for the replacement of heating ventilation, air conditioning, and controls in the M. T. Carter Building. − Gunston Hall. Proposes $200,000 GF in FY 2017 for construction of new water lines. − Central Maintenance Reserve. Proposes $31.0 million GF the first year, $98.4 million GF the second year, and $60.0 million from tax-supported bonds the first year (a total of $189.4 million from all funds) for state agencies and higher education institutions for capital maintenance reserve projects. Maintenance Reserve is used to cover the costs of building maintenance and repair projects that are too large to be covered under day-to-day operating maintenance, but that do not exceed $1.0 million. -

Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority

Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority RESERVOIR WATER QUALITY and MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT June 2018 Acknowledgements In November 2014, DiNatale Water Consultants and Alex Horne Associates were retained by the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority to develop a comprehensive reservoir water quality monitoring program. This proactive approach is a revision from historic water quality management by the Authority that tended to be more reactive in nature. The Authority embraced the use of sound science in order to develop an approach focused on reservoir management. Baseline data were needed for this scientific approach requiring a labor-intensive, monthly sampling program at all five system reservoirs. Using existing staff resources, the project kicked-off with training sessions on proper sampling techniques and use of sampling equipment. The results and recommendations contained within this report would not have been possible without the capable work of the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority staff: • Andrea Terry, Water Resources Manager, Reservoir Water Quality and Management Assessment Project Manager • Bethany Houchens, Water Quality Specialist • Bill Mawyer, Executive Director • Lonnie Wood, Director of Finance and Administration • Jennifer Whitaker, Director of Engineering and Maintenance • David Tungate, Director of Operations • Dr. Bill Morris, Laboratory Director • Matt Bussell, Water Manager • Konrad Zeller, Water Treatment Plant Supervisor • Patricia Defibaugh, Lab Chemist • Debra Hoyt, Lab Chemist • Peter Jasiurkowski, Water Operator • Brian -

Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Minerals Of

VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRG INIA 1988 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE. VIRGINIA 1 988 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 19BB DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY RICHMOND, VIRGIMA O. Gene Dishner, Director COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGIMA DEPARTMENT OF PURCHASES AND SUPPLY RICHMOND Copyright 1988, Commonwealth of Virginia Portions of this publication may be quoted if credit is given to the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources. CONTENTS Page I I I 2 a J A Epidote 5 5 5 Halloysite through 8 9 9 9 Limonite through l0 Magnesite through muscovite l0 ll 1l Paragonite ll 12 l4 l4 Talc through temolite-acti 15 15 l5 Teolite group throug l6 References cited l6 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Location map of I 2. 2 A 4. 6 5. Goethite 6 6. Sawn goethite pseudomorph with unreplaced pyrite center .......... 7 7. 1 8. 8 9. 10. 11. -

A Visual Representation of the Impacts to the Rockfish Valley from the Proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline

A Visual Representation of the Impacts to the Rockfish Valley from the Proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline Standing in the Rockfish Valley on land registered as an historic farm that was cultivated over 250 years, one looks west to see a beautiful swath that sweeps down from Fortunes Ridge to Horizons Village. This view, down the east sidde of the Blue Ridge from Fortunes Point to Horiizons Village, is one of the most important panoramic views in Virginia and sets the scene for all of the economic engines in this area. This panorama contains Horizons conserved land and the acreage of Elk Hill, which is in conservation with an easement held by Virginia Outdoor Foundation. Additionally, State Route 151, which runs down the middle of the Valley, is a Scenic Byway as is Beech Grove Rd and the Blue Ridge Parkway is a National Scenic Byway. The creation of this document is a collaboration between Sarah Collins and Peter Agelasto Sarah Ellis Collins, MLA Peter Agelasto University of Georgia College of Environment & Design 2012 President, Rockfish Valley Foundation University of Virginia School of Architecture 2009 [email protected]; www.rockfishvalley.org; [email protected]; 434.996.3653 434 226 0446; P O Box 235, Nellysford VA 22958 Atlantic Coast Pipeline through Northern Nelson County, Virginia Afton 4 1 2 3 1 Nellysford see map 2 for detail Community Resources Map 1 Towns along ACP Routes 1 Fenton Property, future Fenton Inn ACP Primary Route 2 Wintergreen Gatehouse ACP Alternative Routes 3 Zawatsky property Upper Rockfish River -

Stream Biological Health of Streams and Rivers of the Rivanna River Watershed Wacommunity Watcter Monitoringh for a Healthy Rivanna

stream Biological Health of Streams and Rivers of the Rivanna River Watershed WACommunity waTCter monitoringH for a healthy Rivanna Executive Summary THE RIVANNA RIVER and its tributaries flow through the heart of our neighborhoods and communities, supplying our drinking water and giving us abundant opportunities for fishing, swimming and boating. The value of safe water supplies cannot be overestimated nor should be taken for granted in light of recent hazardous materials spills elsewhere in Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina. Here on the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge, we in the Rivanna watershed enjoy a high quality of life, due in large part to our proximity to forests, waterways and open spaces. Yet a three-year StreamWatch assessment of the ecological health of the Rivanna and its tributaries tells a different story: nearly 70% of our local streams are failing the Virginia state standard for aquatic health. Since 2003, StreamWatch volunteers have been monitoring river health and reporting findings to the community and our government leaders. Our high standards for data quality are recognized by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. Failing to take care of our streams means failing to take care of ourselves. We believe we can and should be doing better as a community to protect our water resources. With modest improvement in land and water management practices, such as planting tree buffers along our streams, and by supporting sound land-use policies and decisions, many of these failing streams can be returned to good health. Our goal as a community should be to return our streams to full health. -

Healthy Watersheds, Healthy Communities

Peter Stutts Healthy Watersheds, Healthy Communities The Nelson County Stewardship Guide for Residents, Businesses, Communities and Government Peter Stutts A joint project of Nelson County, Virginia, Skeo Solutions, the Green Infrastructure Center and the University of Virginia Nelson County’s Natural Resources & Watershed Health Nelson County’s watershed resources – the county’s air, forests, ground water, soils, waterways and wildlife habitat – are closely intertwined with its culture, history and recreation opportunities. Together, these resources provide vital, irreplaceable services integral to citizens’ quality of life, public health and the economy of Nelson County. These resources also cross county boundaries and provide regional benefits. This stewardship guide provides Nelson County’s residents, businesses, communities and government with information on how they can use and manage local land resources to maintain, protect and restore local water quality and healthy watersheds. FORESTS Nelson County has more large, intact areas of forest than most counties in the Virginia Piedmont. Forested land constitutes 80 percent of its land area. More than 249,000 of these acres are ranked by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation as “outstanding to very high quality” for wildlife and water quality protection. Nelson County’s forests contribute $3 million annually to the local economy. WATER Nelson County’s water resources include ground water aquifers and 2,220 miles of waterways, including the Buffalo, James, Piney, Rockfish and Tye Rivers, that extend across nine watersheds. The county’s water resources provide drinking water for most county residents and businesses. SOILS AND AGRICULTURE Farmland constitutes approximately one quarter of Nelson County’s land area – 73,149 acres. -

The Piedmont Environmental Council 2016 Annual Report

ENGAGE • EDUCATE • EMPOWER ANNUAL REPORT · 2016 Dear Friends, t the core of The Piedmont Environmental ` fought to protect important community resources from Council’s work, we strive to engage, educate and the impacts of new electric transmission lines and natural A empower people to protect and improve the places gas pipelines; we all love and call home. Ultimately, we provide ways for ` banded together to erect memorials to displaced people to act directly, to do it themselves. Our work on Blue Ridge families; and Federal, state, and local policy is especially designed to ` acted in countless other ways to preserve what they value encourage and enable direct action. about this place. We’re continually energized by the countless ways that At a time of uncertainty, Virginia’s northern Piedmont Piedmont residents act on their love of this place. stands as an example of how civic engagement works. People participate in the decisions that shape their com- Over the years, Piedmont residents have: munities’ futures. Local governments have acted vigorously VOLUNTEERS PLANTING TREES ALONG A STREAM AT to shape growth in ways that preserve our natural MARRIOTT RANCH DURING OUR ANNUAL FROM THE RAPPAHANNOCK FOR THE RAPPAHANNOCK EVENT. ` made phone calls, written letters and spoken at public resources and rural heritage. Photo by Paula Combs hearings in support of conservation and smart land use decisions; In the past year, more than 60 new families have joined ` purchased more food from local growers and farmers, the hundreds of Piedmont landowners who have chosen ”The Piedmont even growing more themselves; to place their lands under conservation easement. -

This Annotated Checklist Is Meant to Bring Together Both My Own

28 BANISTERIA NO. 43, 201 4 Walker, J. F., O. K. Miller, Jr., & J. L. Horton. Worley, J. F., & E. Hacskaylo. 1959. The effects of 2008. Seasonal dynamics of ectomycorrhizal fungus available soil moisture on the mycorrhizal association assemblages on oak seedlings in the southeastern of Virginia pine. Forest Science 5: 267-268. Appalachian Mountains. Mycorrhiza 18: 123-132. Yahner, R. H. 2000. Eastern Deciduous Forest Ecology Wilcox, C. S., J. W. Ferguson, G. C. J. Fernandez, & and Wildlife Conservation. University of Minnesota R. S. Nowak. 2004. Fine root growth dynamics of four Press, Minneapolis, MN. 295 pp. Mojave Desert shrubs as related to soil and microsite. Journal of Arid Environments 56: 129-148. Banisteria, Number 43, pages 28-39 © 2014 Virginia Natural History Society Dragonflies and Damselflies of Albemarle County, Virginia (Odonata) James M. Childress 4146 Blufton Mill Road Free Union, Virginia 22940 ABSTRACT The Odonata fauna of Albemarle County, Virginia has been poorly documented, with approximately 20 species on record before this study. My observations from 2006 to 2014, along with historical and other recent records, now bring the total species count for the county to 95. This total includes 64 species of dragonflies, which represents 46% of the 138 species known to occur in Virginia, and 31 species of damselflies, which represents 55% of the 56 species known to occur in Virginia. Also recorded here are the observed date ranges for adults of each species and some observational notes. Key words: Odonata, dragonfly, damselfly, Albemarle County, Virginia. INTRODUCTION STUDY AREA For many counties in Virginia, there has been Albemarle County (Fig.