Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe Refers To: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Viewing Archiving 300

Bull. Soc. belge Géol., Paléont., Hydrol. T. 78 fasc. 2 pp. 111-130 Bruxelles 1969 Bull. Belg. Ver. Geol., Paleont., Hydrol. V. 78 deel 2 blz. 111-130 Brussel 1969 THE TYPE-LOCALITY OF THE SANDS OF GRIMMERTINGEN AND CALCAREOUS NANNOPLANKTON FROM THE LOWER TONGRIAN E. MARTINI 1 & T. MooRKENS 2 CONTENT Summary 111 Zusammenfassung 111 Résumé 112 1. Introduction . 112 2. Historical review of some chronostratigraphical conceptions. 114 3. The Eocene-Oligocene transitional strata in Belgium 115 4. Locality details 122 5. The calcareous nannoplankton assemblages 124 6. Conclusions . 125 7. Acknowledgments . 127 8. References 127 SuMMARY. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) considered the Sands of Grimmertingen as the base of his Ton grian stage (Grimmertingen is at present a hamlet in the municipality of Vliermaal in the Eastern part of Belgium). Samples have been taken from the outcrop of the type-locality and from a new boring reaching a depth of 12,5 m, towards the base of this member. Sorne of these sa.mples from both outcrop and boring yielded fairly rich assemblages of calcareous nannoplankton of which a list is given: the assemblages belong to the Ellipsolithus subdistichus zone, the zone which was also recognised in the sand extracted from the molluscs of the type-Latdorfian (Lower Oligocene). The recent sampling of the Grimmertingen-locality also permitted to find fairly rich associations of Hystrichospheres and of planktonic and benthonic Foraminifera, which are under current study. ZusAMMENFASSUNG. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) stellte die Sande von Grimmertingen an die Basis seines ,,Tongrien" (Grimmertingen befindet sich heute im Stadtbereich von Vliermaal im ostlichen Teil von Belgien). -

Memorandum Vlaamse En Federale

MEMORANDUM VOOR VLAAMSE EN FEDERALE REGERING INLEIDING De burgemeesters van de 35 gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde hebben, samen met de gedeputeerden, op 25 februari 2015 het startschot gegeven aan het ‘Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde’. Toekomstforum stelt zich tot doel om, zonder bevoegdheidsoverdracht, de kwaliteit van het leven voor de 620.000 inwoners van Halle-Vilvoorde te verhogen. Toekomstforum is een overleg- en coördinatieplatform voor de streek. We formuleren in dit memorandum een aantal urgente vragen voor de hogere overheden. We doen een oproep aan alle politieke partijen om de voorstellen op te nemen in hun programma met het oog op het Vlaamse en federale regeerprogramma in de volgende legislatuur. Het memorandum werd op 19 december 2018 voorgelegd aan de burgemeesters van de steden en gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde en door hen goedgekeurd. 1. HALLE-VILVOORDE IS EEN CENTRUMREGIO Begin 2018 hebben we het dossier ‘Centrumregio-erkenning voor Vlaamse Rand en Halle’ met geactualiseerde cijfers gepubliceerd (zie bijlage 1). De analyse van de cijfers toont zwart op wit aan dat Vilvoorde, Halle en de brede Vlaamse Rand geconfronteerd worden met (groot)stedelijke problematieken, vaak zelfs sterker dan in andere centrumsteden van Vlaanderen. Momenteel is er slechts een beperkte compensatie voor de steden Vilvoorde en Halle en voor de gemeente Dilbeek. Dat is positief, maar het is niet voldoende om de problematiek, met uitlopers over het hele grondgebied van het arrondissement, aan te pakken. Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde vraagt een erkenning van Halle-Vilvoorde als centrumregio. Deze erkenning zien we als een belangrijk politiek signaal inzake de specifieke positie van Halle-Vilvoorde. De erkenning als centrumregio moet extra financiering aanreiken waarmee de lokale besturen van de brede Vlaamse rand projecten en acties kunnen opzetten die de (groot)stedelijke problematieken aanpakken. -

Koppelteken Voor Een Regio 1950 1969 1970 1989 1990 2009 2010 • Eerste Steen Gordel Van Smaragd (Westrand)

Tina Deneyer 20 jaar ‘de Rand’ Koppelteken voor een regio 1950 1969 1970 1989 1990 2009 2010 • eerste steen Gordel van Smaragd (Westrand) 1991 • verbouwde GC de Moelie 2008 • Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand 1992 • oprichting Vlabinvest 1968 • cultuurraad 1971 • verkiezing 1988 • ‘betonnering’ Wezembeek-Oppem Randfederaties faciliteiten • pacificatiewet: systeem 1993 • GC de Kam rechtstreekse Wezembeek-Oppem 2007 • GC de Muse 2012 • goedkeuring verkiezing • Sint-Michielsakkoord: splitsing BHV splitsing provincie Brabant, rechtstreekse verkiezing Vlaams parlement 1954 • publicatie 1967 • ontwerp-gewestplan: 1972 • Nederlandse 1987 • nieuwe GC de Zandloper 2006 • budget taalpromotie talentelling 1947: Kulturele Raad (NKR) Kaasmarkt Wemmel • Groene Gordel 1994 • start Vlabinvest omvorming tot EVA Tina Deneyer externe tweetalig- Wemmel heid in Drogenbos, Wemmel, Kraainem en Linkebeek 1995 • provincie 20 jaar ‘de Rand’ Vlaams-Brabant 1974 • Kultuurraad Kraainem 2005 • Taskforce Vlaamse 2013 • decretale wijziging: • RINGtv • bescherming Rand jeugd en sport in de • Boesdaalhoeve nieuw deel GC de zes naar vzw ‘de Rand’ • Zandloper Zijp Lijsterbes Kraainem • eerste Gordelfestival • 1963 • taalwet en faciliteiten: Wemmel 1986 • Jazz Hoeilaart onderzoek Mens & • laatste Jazz Hoeilaart naast Drogenbos, • Socio-culturele Raad voortaan in Ruimte • decreet deugdelijk Koppelteken Kraainem, Linkebeek Linkebeek GC de Bosuil bestuur in de publieke en Wemmel ook sector Sint-Genesius-Rode en 2004 • kaaskrabber Wezembeek-Oppem 1996 • actieplan van de voor -

A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Asse Puurs via Liezele Humbeek Mechelen Drijpikkel Puurs via Willebroek Luchthaven Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINT OF INTEREST STOP Dendermonde Boom via Londerzeel Kapelle-op-den-Bos Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Antwerpen Malines - Anvers Boom via Tisselt Verbrande Brug Anvers Stade Roi Baudouin Heysel B2 Koning Boudewijn stadion Heizel Jordaen Pellenberg Heysel Ennepetal Minnemolen Sportcomplex Kerk Vilvoorde Heldenplein Atomium B3 Vilvoorde Station 64 Heizel Vlierkens 260 47 58 Kerk Machelen 820 Machelen A 250-251 460-461 A 230-231-232 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde Heysel Blokken Brussels Expo B3 Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Koningin Fabiola Heizel VTM Drie Fonteinen Parkstraat Aéroport Bruxelles National Windberg Kasteel Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Brussels Airport B8 Zellik Station Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Raedemaekers Brussels National Airport Dilbeek Keebergen Kaasmarkt Robbrechts Cortenbach Kampenhout RTBF 243-820 Kerk Kortenbach Haacht Diamant D6 Hoogveld VRT Kerk Haren-Sud SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Omnisports Haren 270-271-470 Markt Bever De Villegas Buda Haren-Zuid Omnisport Haren Basilique de Koekelberg Rijkendal Militair Hospitaal DOO DGHR Militair Domein Dobbelenberg Bossaert-Basilique Gemeenteplein Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg E2 Guido Gezelle Vijvers Hôpital Militaire 47 Bicoque Aérodrome Bossaert-Basiliek Tweedekker Vliegveld Leuven National Basilica 820 Van Zone tarifaire MTB Louvain 240 Bloemendal Long Bonnier Beyseghem 53 57 -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder -

315 Bus Dienstrooster & Lijnroutekaart

315 bus dienstrooster & lijnkaart 315 Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven Bekijken In Websitemodus De 315 buslijn (Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven) heeft 4 routes. Op werkdagen zijn de diensturen: (1) Bertem Alsemberg: 07:50 (2) Bertem Oud Station: 12:00 (3) Leuven Station Perron 1: 05:45 - 18:45 (4) Sint- Lambrechts-Woluwe Kraainem Metro: 05:45 - 18:45 Gebruik de Moovit-app om de dichtstbijzijnde 315 bushalte te vinden en na te gaan wanneer de volgende 315 bus aankomt. Richting: Bertem Alsemberg 315 bus Dienstrooster 13 haltes Bertem Alsemberg Dienstrooster Route: BEKIJK LIJNDIENSTROOSTER maandag 07:50 dinsdag 07:50 Leuven Station Perron 10 perron 11 & 12, Leuven woensdag 07:50 Leuven J.Stasstraat donderdag 07:50 87 Bondgenotenlaan, Leuven vrijdag 07:50 Leuven Rector De Somerplein Zone B zaterdag Niet Operationeel 5 Margarethaplein, Leuven zondag Niet Operationeel Leuven Dirk Boutslaan 38 Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven Leuven De Bruul 4A Brouwersstraat, Leuven 315 bus Info Route: Bertem Alsemberg Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek Haltes: 13 18 Kapucijnenvoer, Leuven Ritduur: 18 min Samenvatting Lijn: Leuven Station Perron 10, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein Leuven J.Stasstraat, Leuven Rector De Somerplein Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Zone B, Leuven Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven De Bruul, Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Tervuursepoort Leuven Tervuursepoort, Heverlee Egenhovenweg, 1 Herestraat, Leuven Heverlee Berg Tabor, Heverlee Sociaal Hogeschool, Heverlee Bremstraat, Bertem Alsemberg Heverlee Egenhovenweg 116 Tervuursesteenweg, -

The Dutch-French Language Border in Belgium

The Dutch-French Language Border in Belgium Roland Willemyns Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Germaanse Talen, Pleinlaan 2, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium Thisarticle is restricted to adescriptionof languageborder fluctuations in Belgium as faras itsDutch-French portion isconcerned.After a briefdescription of theso-called ‘languagequestion’ in Belgium thenotion of languageborder is discussedin general. Then comesan overviewof thestatus and function of thelanguage border in Belgium and of theactual language border fluctuations as they haveoccurred up to thepresent day. Two problem areas:the ‘ Voerstreek’and theBrussels suburban region are discussedin moredetail. Afterwards language shift and changethrough erosionin Brusselsare analysed as wellas thepart played in thatprocess by linguisticlegislation, languageplanning and sociolinguisticdevelopments. Finally a typology of language borderchange is drawn up and thepatterns of changeare identified in orderto explain and accountforthea lmostunique natureoftheBelgianportion of the Romance-Germanic language border. 1. Introduction Belgium (approximately10 million inhabitants) is a trilingualand federal country,consisting of four different entitiesconstituted on the basisof language: the Dutch-speaking community(called Flanders;58% of the population),the French speaking one (called Wallonia;32%), the smallGerman speaking commu- nity (0.6%)and the Dutch-French bilingual communityof Brussels(9.5%). Since regionalgovernments have legislative power, the frontiersof their jurisdiction, being language borders, are defined in the constitution (Willemyns, 1988). The Belgian portionof the Romance-Germaniclanguage borderis quite remarkablefor mainly two main reasons: (1) itsstatus and function have changed considerablysince the countrycame into existence; (2) itspresent status andfunction arealmost unique ascompared to all the otherportions under consideration.Because of thatit has frequently caughtthe attention(and imagi- nation)of scientistsof variousdisciplines (although,for a long time,mainly of historians;Lamarcq & Rogge,1996). -

Subsidiëring in Verban

Vraag nr. 15 2. Betaald werkingsbudget (in euro) voor het van 17 oktober 2003 schooljaar 2002 – 2003 van de heer LUK VAN NIEUWENHUYSEN Gemeente Werkingsbudget (02-03) Franstalige faciliteitenscholen – Subsidiëring Drogenbos 79.700,97 In verband met het onderwijs in de faciliteitenge- meenten zou ik van de minister graag het volgende Kraainem 133.008,25 vernemen met betrekking tot het schooljaar Linkebeek 96.770,00 2002-2003. Sint-Genesius-Rode 312.610,11 Wemmel 241.146,16 1. Hoeveel bedroegen in totaal de uitgekeerde weddesubsidies per gemeente voor het Fr a n s t a- Wezembeek-Oppem 342.931,65 lig onderwijs in de zes Randgemeenten rond Ronse 36.583,32 Brussel en in Ronse ? Totaal 1.242.750,46 2. Welke bedragen werden er uitgekeerd aan wer- k i n g s- en uitrustingssubsidies voor het facilitei- 3. Kostprijs per leerling (in euro) in het basison- tenonderwijs ? derwijs voor het schooljaar 2002 –2003 3. Hoe hoog lag de kostprijs per leerling van het lager en het middelbaar onderwijs ? Soort onderwijs Kostprijs per leerling 4. Hoeveel leerlingen telde het Franstalig onder- Gewoon basisonderwijs 3.407,74 wijs per faciliteitengemeente in Vlaanderen tij- Buitengewoon basisonderwijs 9.982,84 dens het bovenvermelde schooljaar ? (Bron : "2002 – 2003 : basisonderwijs in beeld") 5. Zijn er nog andere kosten verbonden aan de aanwezigheid van Franstalige faciliteitenscholen in Vlaanderen ? 4. Gemeente Aantal leerlingen Welke zijn die in voorkomend geval ? Drogenbos 178 Kraainem 286 6. Kan de minister ter vergelijking de schoolbevol- Linkebeek 239 kingscijfers in het Nederlandstalig onderwijs in de betrokken gemeenten meedelen ? Sint-Genesius-Rode 755 Wemmel 545 Wezembeek-Oppem 795 Antwoord Ronse 245 Basisonderwijs Totaal 3.043 1. -

Wij Werken Aan Het Spoor Tussen Halle En Vilvoorde Tijdens Het Weekend Van 7 Tot En Met 29 Oktober Tijdens Het Weekend Van 18 Tot En Met 26 November

nmbs.be LIJN 26 Halle - Vilvoorde Wij werken aan het spoor tussen Halle en Vilvoorde Tijdens het weekend van 7 tot en met 29 oktober Tijdens het weekend van 18 tot en met 26 november Leuven Herent KortenbergBrussels BordetAirport-ZaventemBrussel-SchumanBrussel-LuxemburgEtterbeek Boondaal Diesdelle Sint-Job Linkebeek Sint-Genesius-RodeWaterloo Eigenbrakel Richting Eigenbrakel - Leuven De IC-treinen Eigenbrakel - Leuven rijden niet tijdens de werken.De reizigers in Eigenbrakel, Waterloo, Sint-Genesius-Rode en Linkebeek die naar Waterloo, Sint-Genesius-Rode en Linkebeek willen, kunnen de S1-treinen Nijvel - Brussel-Centraal - Antwerpen-Centraal nemen. De reizigers in Waterloo, Sint-Genesius-Rode en Linkebeek die naar Etterbeek, Brussel-Luxembourg, Brussel-Schuman, Brussels Airport-Zaventem, Herent, Kortenberg, Leuven willen, kunnen de S1-treinen Nijvel - Brussel-Centraal - Antwerpen-Centraal nemen tot Brussel-Zuid, vanwaar ze hun reis kunnen verderzetten. De reizigers in Eigenbrakel die naar Etterbeek, Brussel-Luxemburg, Brussel-Schuman, Brussels Airport - Zaventem, Herent, Kortenberg, Leuven willen, kunnen de IC-treinen Charleroi-Zuid - Brussel-Centraal - Antwerpen-Centraal nemen tot Brussel-Zuid, vanwaar ze hun reis kunnen verderzetten. De reizigers van en naar Bordet, Boondaal, Diesdelle en Sint-Job worden verzocht om de bus/tram van de Lijn/MIVB te nemen (zie Alternatieven De Lijn/MIVB). Richting Leuven - Eigenbrakel De IC-treinen Leuven - Eigenbrakel rijden niet tijdens de werken.De reizigers in Leuven, Herent, Kortenberg kunnen de S2-treinen Leuven - Brussel-Centraal - ‘s-Gravenbrakel nemen.De reizigers in Herent, Kortenberg die naar Brussel-Schuman, Brussel-Luxemburg, Etterbeek, Linkebeek,Sint-Genesius-Rode, Waterloo en Eigenbrakel willen, kunnen de S2-treinen Leuven - Brussel-Centraal - ‘s-Gravenbrakel nemen tot Brussel-Noord, vanwaar ze hun reis kunnen verderzetten. -

The Impact of the Extension of the Pedestrian Zone in The

THE IMPACT OF THE EXTENSION OF THE PEDESTRIAN ZONE IN THE CENTRE OF BRUSSELS ON MOBILITY, ACCESSIBILITY AND PUBLIC SPACE Imre Keserü, Mareile Wiegmann, Sofie Vermeulen, Geert te Boveldt, Ewoud Heyndels & Cathy Macharis VUB-MOBI – BSI-BCO Original Research EN Since 2015, the Brussels pedestrian zone has been extended along boulevard Anspach. What impact did this have on travel and visiting behaviour, the perceived accessibility of the centre, and the quality of its public space? Brussel Mobiliteit (Brussels Capital Region) commissioned a large-scale follow-up survey to VUB-MOBI & the BSI-BCO to answer this question and monitor the effects before and after the renewal works. Brussels Metropolitan Area (BMA) inhabitants, city-centre employees and pedestrian zone visitors were questioned. This paper presents the most important findings from the 4870 respondents of the pre-renewal survey. A more detailed analysis will be available in the full research report (forthcoming, VUB-MOBI – BSI-BCO & Brussel- Mobiliteit). In general, more respondents were in support of a car-free Blvd Anspach than against it. Most visitors go to the new pedestrian zone for leisure-related purposes. Overall, the users are also mostly regular visitors, including inhabitants of the city centre and other Brussels inhabitants. In terms of appreciation of public space, the most problematic aspects are cleanliness and safety concerns whether during the day or by night. Furthermore, 36% of the BMA respondents stated that the closure for cars has influenced their choice of transport when going to the city-centre. Many of them use public transport more often. Lastly, the authors put forward recommendations to improve the pedestrian zone considering the survey’s results. -

Netplan Vervoergebied Brussel

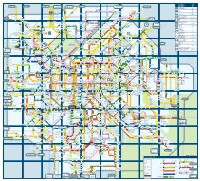

Vervoergebied Brussel BELBUSSEN DENDERMONDE Leest Belbus Lebbeke - Buggenhout DENDERMONDE Belbus Ninove - Haaltert Belbus Faluintjes - Opwijk MECHELEN Belbus Geraardsbergen Malderen Hombeek Belbus Heist-op-den-Berg - Bonheiden - Putte LONDERZEEL Denderbelle BUGGENHOUT KAPELLE- O/D-BOS Steenhuel Hever LEBBEKE Hofstade SCHAAL 1 - 100 000 Nieuwenrode ZEMST Humbeek OPWIJK Weerde Baardegem Elewijt MERCHTEM Eppegem Beigem Wolvertem School- en marktbussen KAMPENHOUT overlappende belbusgebieden & belbusgrens Naast al deze voorgestelde lijnen biedt De Lijn haar reizigers ook Mazenzele Brussegem een groot aantal school- en marktbussen aan. Meldert MEISE VILVOORDE Om dit netplan overzichtelijk te houden, zijn ze niet weergegeven. Hamme Perk GRIMBERGEN Peutie Hun haltelijsten en trajecten vind je terug in de lijnfolder Mollem Berg ASSE hoofdhalte met belangrijke overstap & Hekelgem Melsbroek belbushalte AALST STEENOKKERZEEL Erps-Kwerps Ede Kobbegem Strombeek-Bever WEMMEL MACHELEN eindhalte van 1 lijn op HAALTERT Teralfene AFFLIGEM Welle meervoudige halte Essene Diegem eindhalte van meer dan 1 lijn op ZAVENTEM meervoudige halte Heldergem Jette TERNAT Ganshoren Sint-Stevens- Nossegem Denderhoutem Woluwe BRUSSEL Sint-Katharina- Sint-Agatha- Schaarbeek Lombeek Berchem Evere LIEDEKERKE Sint-Martens- Sterrebeek Bodegem Sint-Jans- KRAAINEM Borchtlombeek Molenbeek NINOVE Wambeek Sint-Joost-ten-Node Aspelare Pamel Strijtem DILBEEK Sint-Lambrechts- WEZEMBEEK- Itterbeek Sint-Gillis Woluwe ROOSDAAL OPPEM Voorde Schepdaal Anderlecht Etterbeek Apelterre- Elsene -

The Dutch-French Language Border in Belgium

The Dutch-French Language Border in Belgium Roland Willemyns Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Germaanse Talen, Pleinlaan 2, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium Thisarticle is restricted to adescriptionof languageborder fluctuations in Belgium as faras itsDutch-French portion isconcerned.After a briefdescription of theso-called ‘languagequestion’ in Belgium thenotion of languageborder is discussedin general. Then comesan overviewof thestatus and function of thelanguage border in Belgium and of theactual language border fluctuations as they haveoccurred up to thepresent day. Two problem areas:the ‘ Voerstreek’and theBrussels suburban region are discussedin moredetail. Afterwards language shift and changethrough erosionin Brusselsare analysed as wellas thepart played in thatprocess by linguisticlegislation, languageplanning and sociolinguisticdevelopments. Finally a typology of language borderchange is drawn up and thepatterns of changeare identified in orderto explain and accountforthea lmostunique natureoftheBelgianportion of the Romance-Germanic language border. 1. Introduction Belgium (approximately10 million inhabitants) is a trilingualand federal country,consisting of four different entitiesconstituted on the basisof language: the Dutch-speaking community(called Flanders;58% of the population),the French speaking one (called Wallonia;32%), the smallGerman speaking commu- nity (0.6%)and the Dutch-French bilingual communityof Brussels(9.5%). Since regionalgovernments have legislative power, the frontiersof their jurisdiction, being language borders, are defined in the constitution (Willemyns, 1988). The Belgian portionof the Romance-Germaniclanguage borderis quite remarkablefor mainly two main reasons: (1) itsstatus and function have changed considerablysince the countrycame into existence; (2) itspresent status andfunction arealmost unique ascompared to all the otherportions under consideration.Because of thatit has frequently caughtthe attention(and imagi- nation)of scientistsof variousdisciplines (although,for a long time,mainly of historians;Lamarcq & Rogge,1996).