Intercity Bus Industry in Texas 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Planning Documentation

Project Planning Documentation Overview of Project Project funding will be used to complete necessary preliminary engineering and NEPA for a new 250 mile high-speed core express service between Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston. Based on the preliminary planning summarized in this document, the Dallas-Fort Worth to Houston route could utilize one of three routes analyzed, consisting of a BNSF route through Teague, a UPRR route through College Station, or a new green field route that parallels I-45. Additionally, all three of the routes include segments of the UPRR Terminal and West Belt Subdivisions in order to connect to the existing passenger rail station in downtown Houston and a small portion of the UPRR Dallas Subdivision to connect to the existing passenger rail station (Union Station) in Dallas. Purpose and Need The purpose of the Dallas/Fort Worth to Houston core express service preliminary engineering and NEPA documentation is to prepare the project for the next stage of final design and construction. The Dallas/Fort Worth to Houston corridor has been included in the Texas Rail Plan as well as a research study performed by the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI), and the America 2050 report as a key corridor with need for high speed rail service. Texas Rail Plan TxDOT completed and published the Texas Rail Plan in November 2010, which included a short term and long term program for passenger rail. The Dallas to Houston corridor was included in the short term program for preliminary planning and in the long term program for further development of the project. -

When the Wheels on the Bus Stop Going Round and Round: Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities in Public Transportation

February 2015 errata On May 28, 2015, a correction was made to paragraph four under “BLS survey of occupational injuries and illnesses” in this article. The sentence, as originally published, incorrectly identified the cost of security cameras on buses as $18,000 per camera rather than per bus. When the wheels on the bus stop going round and round: occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities in public transportation Injuries and illnesses to bus drivers endanger not only their lives but also the lives of their passengers. In 2013, approximately 5,780 transit and intercity bus drivers experienced a days-away-from-work injury or illness while on the job. This article explores occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities to bus drivers and urban transit workers and examines how individual transit systems are collecting and analyzing their own employee safety data. The findings reveal that mass transit systems have taken steps to protect their employees from harm on the job and that injuries and illnesses to bus drivers and urban transit workers have declined in recent years. In October 2012, a Washington (DC) Metropolitan Area Gina Dowdell Hunter Transit Authority (WMATA) bus driver was hospitalized after [email protected] a rock was thrown through an open window and hit her Gina Dowdell Hunter is an economist in the Office 1 head while she was driving. In August 2013, a gunman of Safety, Health and Working Conditions, U.S. rushed on to a King County metro bus in downtown Seattle Bureau of Labor Statistics. and shot the driver during rush hour.2 These sorts of violent attacks involving bus drivers endanger not just the bus drivers but the passengers as well. -

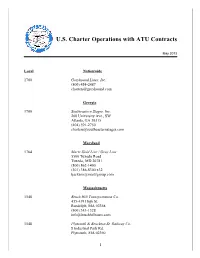

U.S. Charter Operations with ATU Contracts

U.S. Charter Operations with ATU Contracts May 2013 Local Nationwide 1700 Greyhound Lines, Inc. (800) 454-2487 [email protected] Georgia 1700 Southeastern Stages, Inc. 260 University Ave., SW Atlanta, GA 30315 (404) 591-2750 [email protected] Maryland 1764 Martz Gold Line / Gray Line 5500 Tuxedo Road Tuxedo, MD 20781 (800) 862-1400 (301) 386-8300 x32 [email protected] Massachusetts 1548 Brush Hill Transportation Co. 435-439 High St. Randolph, MA 02368 (800) 343-1328 [email protected] 1548 Plymouth & Brockton St. Railway Co. 8 Industrial Park Rd. Plymouth, MA 02360 1 (508) 746-0378 x226 [email protected] 1363 & 1512 Peter Pan Bus Lines, Inc. / Bonanza Bus Lines, Inc. P.O. Box 1776 Springfield, MA 01102-1776 (800) 243-9560 (800) 334-6464 (Boston Area) [email protected] Minnesota/Missouri 1498 Jefferson Bus Lines 2100 E. 26th St. Minneapolis, MN 55404 (612) 359-3467 [email protected] [email protected] New Jersey 1317 DeCamp Bus Lines 101 Greenwood Avenue P.O. Box 581 Montclair, NJ 07042 (800) 631-1281 (973) 783-7500 x240, 241, 242 1614 Lakeland Bus Lines, Inc. 425 E. Blackwell St. Dover, NJ 07801 (800) 367-0601 [email protected] 824 Raritan Valley Bus Service P.O. Box 312 Metuchen, NJ 08840 (800) 339-4306 [email protected] New York 1592 Chenango Valley Bus Lines, Inc. 2 Coach USA - Southern Tier/Binghamton (800) 647-6471 [email protected] 1342 Grand Tours 5355 Junction Road Lockport, NY 14094 (800) 847-4887 [email protected] Pennsylvania 1342 Coach USA - Erie 501 East 19th Street Erie, PA 16503 (800) 352-0979 [email protected] [email protected] 1119 Frank Martz Coach Co. -

Attacks on Bus Operators and Passengers

Sensitive But Unclassified Material For Official Use Only Attacks on Bus Operators and Passengers Special Report Prepared by the ST, PT and OTRB ISACs May 4, 2015 Purpose In light of recent violent incidents targeting transit operators in numerous areas around the globe, the Surface Transportation (ST), Public Transportation (PT), and Over the Road Bus (OTRB) ISACs are providing this special report for your general security awareness. The application of any standards or guidance discussed herein is strictly voluntary. The practices implemented by rail, transit, and OTRB systems may be either more or less restrictive than any recommended practices or guidance given in this document. In some cases, federal and/or state regulations govern portions of public transit systems’ operations. In those cases, government regulations should take precedence over the information or guidance provided herein. Organizations should consult their own Agency’s/Organization’s policies and guidance before taking any actions based on the information presented in these documents. This document supplements guidance and analysis already provided in daily reports produced by the ST, PT, & OTRB ISACs. Of note, the last page of this report lists references for additional information. To contact an ST and PT ISAC analyst please call 866-784-7221, or email [email protected]. To contact an OTRB ISAC analyst please call 877-847-5510, or email [email protected] 1 Sensitive But Unclassified Material For Official Use Only Introduction The security of transit system and interstate bus operators has become an increasing concern for many metropolitan areas. Some attribute the perceived rise in attacks against operators as an artifact of increased reporting, but when that element of information is factored into the analysis, there still appears to be a notable surge in violent behavior targeting transit workers; particularly against bus drivers, who may remain the most vulnerable. -

Pennscore Operator Training Manual

O P E R A T O R T R A I N I N G M A N U A L April, 2002 PennSCORE Operator Training Manual This manual was the brainchild of, and was originally prepared by, Dave Kilmer of Red Rose Transit Authority as part of the PennSCORE program. The manual is designed to be used by transit systems in PA for training new bus operators. It is also designed as a tool for PennSCORE graduates to use in training. This manual is generic, which means that the material contained herein can be used in many different transit environments. Information specific to a particular system, such as route descriptions, needs to be added in the appropriate sections. These sections contain notes suggesting the addition of system-specific information. Places where other training resources might be appropriate are also noted. These resources are typically videos, many of which were used in the PennSCORE program—all are available from PennTRAIN Comments and suggestions from Jim Parks and Dennis Fuge, Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTRAN), are greatly appreciated. They took the generic manual and added system-specific material for use at CamTRAN. A copy of their version is also available from PennTRAIN as an example of how this manual can be adapted for local use. Copies of this manual are available from PennTRAIN. For more information contact Cindy Conaway at 800-847-0333, [email protected]. ii PennSCORE Operator Training Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 What is PennScore?.........................................................................................................................................2 1.2 History of System Name (insert brief History)................................................................................................2 1.3 Training Outline ..............................................................................................................................................3 2. -

Virginia Administrative Code

Virginia Administrative Code Chapter 70 - REGULATIONS GOVERNING multifunction school activity buses. These vehicles PUPIL TRANSPORTATION are not approved for transporting students to and from school or school-related activities. Part I Definitions "School bus" means any motor vehicle other than a station wagon, automobile, truck, or commercial bus that is (i) designed and used primarily for the 8VAC20-70-10. Definitions. transportation of pupils to and from public, private, The following words and terms when used in this or religious schools, or for the transportation of chapter shall have the following meanings unless the pupils who are physically handicapped to and from a context clearly indicates otherwise: sheltered workshop; (ii) painted yellow with the words "School Bus" in black letters of a specified "Classroom instruction" means training provided by size on the front and rear; and (iii) equipped with a qualified driver instructor through lectures, warning devices prescribed in § 46.2-1090 of the demonstrations, audio-visual presentations, Code of Virginia. A yellow school bus may have a computer-based instruction, driving simulation white roof provided such vehicle is painted in devices, or similar means. Instruction occurring accordance with regulations and specifications of the outside a classroom is included if it does not involve Department of Education. actual operation of a school bus and its components by the student. "Specially equipped bus" means a school bus designed, equipped, or modified to accommodate "Color-black" means federal standard No. 595, black. students with special needs. "Color-yellow" means national school bus yellow "Type A school bus" means a conversion bus School Bus Manufacturers Technical Council constructed utilizing a cutaway front-section vehicle (SBMTC) color standard 008. -

As of May 13)

MOTORCOACHES ROLLING FOR AWARENESS RALLY PARTICIPANTS (as of May 13) Accounts (by State) City State John Hall's Alaska Tours and Transportation Anchorage AK Camelot Charters Pell City AL Cline Tours Birmingham AL E & J Tours Birmingham AL Gulf Coast Tours Mobile AL Inventive Tours Tuscaloosa AL Kelton Tours Unlimited LLC Gadsden AL Southeastern Motor Coach, Inc. Birmingham AL Southern Coaches Dothan AL Spirit Coach LLC Madison AL Takers Transportation Huntsville AL Thrasher Brothers Trailways Vestavia Hills AL Tuscaloosa Charter Services Tuscaloosa AL Vineyard Tours, LLC St. Stephens AL Vision Express Tours Montgomery AL Arrow Coach Lines Inc Little Rock AR Little Rock Coaches Little Rock AR Mountain Home Charter Service, Inc. Mountain Home AR JET Limousines & Transportation LLC Phoenix AZ Amador Stage Lines Sacramento CA BEST-VIP Chauffeured Worldwide Santa Ana CA BUS-TECH Sacramento CA Empire Transportation Services FONTANA CA GCLA Los Angeles CA Golden West Travel, LLC Pleasanton CA Highline Charter inc. San Diego CA LA Charter Bus Lines Los Angeles CA Pacific Coachways Charter Services Garden Grove CA Royal Coach Tours San Jose CA Carreras Tours, LLC. Ontario CA Storer San Francisco San Francisco CA Transportation Charter Services, Inc Orange CA Ramblin Express Denver CO Bohannon & Vines Transportation Group, Llc Milford CT Coach Tours Brookfield CT DATTCO, Inc New Britain CT JB Tours &Travel West Haven CT Land Jet Inc Waterbury CT Post Road Stages South Windsor CT Post Road Stages South Windsor CT Rukstela Charter Service Eastford CT Town and Country Transportation Co New Britain CT Destination DC Washington DC International Spy Museum Washngton, DC DC My Dream Tour LLC Washington DC DC Delaware Express Newark DE Rohans Bus Service Inc. -

North Dakota

NORTH DAKOTA SCHOOL BUS DRIVER’S GUIDE MARCH 2015 EDITION DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION Kirsten Baesler, STATE SUPERINTENDENT Bismarck, North Dakota 58505-0440 2 A MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION Over 40,000 students are transported each day to North Dakota schools in school buses. The safety of these students and the efficiency of a district's transportation program depends on the dedicated men and women who accept the important responsibility of driving our school buses. This publication is the thirteenth edition of the handbook for North Dakota school bus drivers. We hope that this handbook answers many questions and gives school bus drivers the necessary guidelines to perform effectively and efficiently. Driving a school bus involves much more than merely driving a vehicle on the highways. The school bus driver must also be responsible for the safety and welfare of children, must be teacher by example, must promote good public relations, and must understand how to properly use and care for the school bus, a complex and expensive piece of equipment. The purpose of this guide is to provide each school bus driver with the basic information needed to develop the skills, attitudes, and knowledge that result in safe and efficient driving. It is my sincere hope that each of North Dakota's school bus drivers will study and properly apply the information presented in this guide to assure a safer transportation program for our students. Driving a school bus is one of the most important jobs we have in our school systems. You carry our state’s most precious resource. -

Crime Prevention That Works: Documentation C: the Care of Public Transport in ='----Centre the Netherlands

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ... Henk van Andel I~ research and I) Crime prevention that works: documentation c: the care of public transport in ='----centre the Netherlands . N ·1/88 / ((o/$. 2- Henk van Andel I~ research and [) Crime prevention that works: documentation (: the care of public transport in centre the N,etherlands 116152 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute 01 Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organizalion originating it. Points of view or opinions sta/Ad in Ihis documenl are those of the authors and do no! neces:;arily represent the official position or policies of the National ittsiitute of Justice. Permission to reproduce Ihis copyrighted malerial has been granted by ~inistry of Justice The NETHERLAND~S~ __________ Ministry of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Netherlands 1988 Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. " 1/88 Contents Swnmary 1 Introduction 2 Description of the measures 2.1 SIC project 2.2 Change in boarding procedure on the bases 3 Design of the evaluation 4 Results 4.1 Fare-dodging tI f 4.2 Safety 4.3 Vandalism 4.4 Information 4.5 What the changes mean to passengers and staff 5 Evaluation 5.1 Deployment of SIC's 5.2 Financial costs and benefits of the SIC project 5.3 Financial costs and benefits of the new boarding procedure on the buses 5.4 Social benefits 6 Discussion ~ Notes \ References (, 1 Summary An experiment has been carried out in the Dutch public transport system to tackle fare-dodging, vandalism and aggression. -

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

Dallas to Houston High-Speed Rail Final Environmental Impact Statement

Dallas to Houston High-Speed Rail Final Environmental Impact Statement ERRATA AND UPDATED INFORMATION FRA has identified several statements in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) which require correction or clarification. In addition, FRA Is providing new and/or updated information from the release of the Final EIS. This updated information and/or minor corrections to language within the Final EIS, are not considered significant, and do not change the analysis or conclusions of the Final EIS. This information does not trigger the need to prepare a supplement, per the requirements of the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality National Environmental Policy Act regulations (40 CFR 1502.9(c)(1)). Page in Location/Section Final in Final EIS EIS Issue Correction or Update ES.2, Executive ES-3 Correction provided by Text is corrected as shown: Summary, TCRR on safety record and The Project includes the deployment of an electric-powered HSR system based on Central Japan Railway Description of for Tokaido Company’s Tokaido Shinkansen system. Accident statistics are not available for systems operating Project 2-1 Shinkansen HSR lines. technology comparable to the Project; however, Japan’s Tokaido Shinkansen HSR, which operates a and similar technology, has had no passenger fatalities resulting from a trainset accident, such as a derailment or collision, since the service began over 50 years ago.8, 9 The technology has a proven safety record with 2.2.1, only one three earthquake-related derailments since the service began, which resulted in no passenger Alternatives injuries. Considered, _________________ Technology 8 The only injuries and/or fatalities reported in association with the Tokaido Shinkansen HSR system was were related to another single passenger’s suicide by self-immolation on June 30, 2015. -

Workshop Agenda

Monterey-Salinas Transit District Strategic Planning January 13, 2020 9:00 AM – 11:15 AM WORKSHOP AGENDA I. MST Overview: 9:00 – 9:30 AM (a). Performance Dashboards (b). Strategic Plan and Action Plan (c). 2020 Capital Projects and Transit Services II. Measure Q Mobility Programs Update 9:30 – 9:45 AM III. MST Employee Recruitment / Retention Issues 9:45 – 10:15 AM IV. Partnerships and New Services Initiatives Update 10:15 – 10:45 AM V. Zero Emission Bus/Innovative Clean Transit Strategy Update 10:45 – 11:00 AM VI. Performance Incentives 11:00 – 11:15 AM VII. Adjourn to CLOSED SESSION 11:15 AM – 12:00 PM Note: Times are approximate Blank Page I (a). PERFORMANCE DASHBOARDS Attached are FY 20 Year to Date performance dashboards, FY 2018 – 2020 Strategic Plan performance goal status update, FY 20 Action Plan status update, and a listing of major capital projects being undertaken by staff. Executive Staff will be on hand to answer any questions you may have regarding these items. The current Performance Dashboard metrics have been in place and reported to the MST Board in a variety of formats for decades. These metrics are the same as those traditionally utilized by transit operators and regulators and have been designed to allow public transit operator management to operate their services more “like a business” to ensure the best use of scarce taxpayer funds. • Safety – Miles Travelled Between Preventable Accidents • Reliability – On-time Performance, Percent of Scheduled Trips Delivered, Miles Travelled between Mechanical Failure • Effectiveness – Ridership Growth/Decline • Efficiency – Passengers Per Hour, Cost per Hour, Farebox Recovery • Financial Stability – Actual Costs vs Budget In recent years some public transit advocates have argued that there may be better measures to track performance guided by community values.