Heroes, Saints, and Sages Many Asanas Take Their Names From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

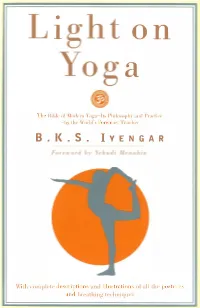

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga ii Teaching Hatha Yoga TEACHING HATHA YOGA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Daniel Clement with Naomi Clement Illustrations by Naomi Clement 2007 – Open Source Yoga – Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada iii Teaching Hatha Yoga Copyright © 2007 Daniel Clement All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the copyright owner, except for brief reviews. First printing October 2007, second printing 2008, third printing 2009, fourth printing 2010, fifth printing 2011. Contact the publisher on the web at www.opensourceyoga.ca ISBN: 978-0-9735820-9-3 iv Teaching Hatha Yoga Table of Contents · Preface: My Story................................................................................................viii · Acknowledgments...................................................................................................ix · About This Manual.................................................................................................ix · About Owning Yoga................................................................................................xi · Reading/Resources................................................................................................xii PHILOSOPHY, LIFESTYLE & ETHICS.........................................................................xiii -

Skanda Purana 81.100, Vamana Purana 10.000, Kurma Purana 17.000, Matsya Purana 14.000, Garuda Purana 18.000, Brahmanda Purana 12.000

Bildnisse von Skanda, wie Er heute dargestellt wird. Für Ihnen unbekannte Begriffe und Charaktere nutzen Sie bitte mein Nachschlagewerk www.indische-mythologie.de. Darin werden Sie auch auf detailliert erzählte Mythen im Zusammenhang mit dem jeweiligen Charakter hingewiesen. Aus dem Englischen mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Siva Prasad Tata. www.hindumythen.de Dakshas Feindseligkeit gegenüber Shiva Sati, die Tochter von Daksha, heiratete Shiva. Daksha vollzog eine groß angelegte Opferzeremonie, zu der er alle wichtigen Persönlichkeiten einlud, doch seinen Schwiegersohn vergaß er. Als Sati davon hörte bat sie Shiva um Erlaubnis, teilzunehmen, ungern stimmte Er zu und schickte Seine Himmlischen Heerscharen zum Schutze Satis mit. Sati springt ins Opferfeuer Als Sati den Opferplatz erreichte sah sie wer alles eingeladen war, Götter, Weise und Asketen. Sie wurde sehr traurig darüber, dass ihr Vater ihren Gatten nicht eingeladen hatte. In Rage geriet sie, als sie feststellen musste, dass für Shiva auch kein Anteil des Opfers vorgesehen war, während andere Götter reich bedacht wurden. Als Daksha Sati bemerkte erklärte er ihr, warum er Shiva nicht eingeladen hatte: ‚Er ist die Verkörperung des Übels, der Herr der Geister, Kobolde und niederen Kräfte.’ Diese Demütigung ihres Gatten vor versammelter Gesellschaft erzürnte Sati dermaßen, dass sie sich entschloss ihrem Leben ein Ende zu setzen, sie sprang in das Opferfeuer. Alle waren starr vor Entsetzen. Als Shiva davon erfuhr schnitt Er sich ein paar Haare ab und schlug damit gegen einen Berg, ein Donnerschlag erschallte und Virabhadra manifestierte sich im Bruchteil einer Sekunde. Shiva befahl Virabhadra, den Tod Satis zu rächen. Mit einer gewaltigen Armee von Sturmgöttern macht er sich auf den Weg zu Dakshas Opferplatz und griff die versammelten Teilnehmer an. -

Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha

Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha With kind regards, and prem Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha Swami Satyananda Saraswati Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar, India YOGA PUBLICATIONS TRUST Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha is internationally recognized as one of the most systematic manuals of hatha yoga available. First published in 1969, it has been in print ever since. Translated into many languages, it is the main text of yoga teachers and students of BIHAR YOGA ® – SATYANANDA YOGA ® and numerous other traditions. This comprehensive text provides clear illustrations and step by step instructions, benefits and contra-indications to a wide range of hatha yoga practices, including the little-known shatkarmas (cleansing techniques). A guide to yogic physiology explains the location, qualities and role of the body’s subtle energy system, composed of the pranas, nadis and chakras. Straightforward descriptions take the practitioner from the simplest to the most advanced practices of hatha yoga. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha is an essential text for all yoga aspirants. Swami Satyananda Saraswati founded the Bihar School of Yoga, India, in 1963. He interpreted the classical practices of yoga and tantra for application in modern society, inspiring an international yoga movement for the upliftment of humanity. © Bihar School of Yoga 1969, 1973, 1996, 2008, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Yoga Publications Trust. The terms Satyananda Yoga® and Bihar Yoga® are registered trademarks owned by International Yoga Fellowship Movement (IYFM). The use of the same in this book is with permission and should not in any way be taken as affecting the validity of the marks. -

Saivism in Odisha

October - 2013 Odisha Review Saivism in Odisha Dr. Gourishankar Tripathy Origin of Saivism traced back to the period of and Saivas during that period at the manner in Harappa and Mohenjodaro centered round with which a Buddhist monument was converted into Vedic civilization. In India it is one of the oldest a phallic emblem. A tradition seems to have been forms of religions. From very early times, it would found in Ekamra Purana where it has been have existed in ODISHA. As attested to by described the history of Bhubaneswar from the archaeological monuments, origin of Saivism in orthodox stand-point. There was a deadfall war the then Orissa can be traced back to 4th- which is said to have taken place between demons 5th century A.D. with its changing fortune in and Gods on the bank of the river Gandhabati. history. By the 4th-5th century A.D. Saivism This river is now known as Gang flowing in the became the dominant form of religion of Orissa close proximity of Bhubaneswar. In this war when both Jainism and Buddhism have receded demons were defeated and the Gods came back to the background. victorious with the help of Mahadev Siva. By a In the Bhaskareswar temple at traditional account, it is supported by archaeological evidence. If we conclude that the Bhubaneswar, it has been observed a huge Siva th Linga which was originally a part of Asokan Pillar 5 century A.D. was the period of conflict, we built before Christ. From the close proximity of shall not be far from truth that the Buddhism was defeated by Saivism. -

Iyengar® Yoga Zertifizierungshandbuch

Iyengar® Yoga Zertifizierungshandbuch Stand: Januar 2019 Impressum Dieses Handbuch wird von Iyengar Yoga Deutschland e. V. (IYD) herausgegeben. 1. Auflage April 2003 2. Auflage Januar 2004 3. Auflage Januar 2005 4. Auflage Januar 2006 5. Auflage März 2009 6. Auflage Dezember 2010 7. Auflage Februar 2012 8. erw. und neu bearb. Auflage Januar 2019 © 2003‒2019 Iyengar Yoga Deutschland e. V. „Iyengar“® wird mit Erlaubnis des Markeninhabers verwendet. 2 Impressum „ Unterrichten ist eine schwierige Kunst, aber es ist der beste Dienst, den du der Menschheit erweisen kannst.“ B. K. S. Iyengar „ Wissen ist immer etwas Universelles. Es ist nicht nur für einzelne Personen. Es ist nichts Individuelles, aber jedes Individuum steuert etwas dazu bei. Wenn Wissen in die richtige Richtung geht und die Unwissenheit vertreibt, führt es uns alle in die gleiche Richtung. So lerne ich also, wenn du lernst. Wenn du fühlst und verstehst, gibt mir das Wissen. Auf ähnliche Weise beginnst du zu verstehen, wenn ich dir Wissen vermittle.“ Geeta S. Iyengar Liebe Prüfungskandidatin, lieber Prüfungskandidat, das Zertifizierungsgremium (ZG) und der Vorstand des Iyengar Yoga Deutschland e. V. freuen sich über dein Interesse, ein zertifizierter Lehrer oder eine zertifizierte Lehrerin werden zu wollen beziehungsweise deinen derzeitigen Level zu erweitern. Der Ablauf der Zertifizierung ist seit Anfang der 1990er-Jahre unter der Anleitung von B. K. S. Iyengar (1918– 2014) und Geeta S. Iyengar (1944–2018) entwickelt und verfeinert worden. Wir hoffen, dass diese Broschüre den Ablauf der Zertifizierung verständlich macht, sodass du weißt, welcher Standard erwartet wird, welches Wissen du mitbringen musst und wie du geprüft wirst. Wenn du Fragen oder Bemerkungen hast, richte sie bitte an die Geschäftsstelle des IYD. -

Exercises & Yoga Postures for Health

Exercises & Yoga Postures for Health by Nirankar S. Agarwal, Ph.D. HealthyLongevity™ - EasyDoPreCare™ & Reversal of Decay © 2018 Nirankar S. Agarwal, Ph.D. 1 EXERCISES & YOGA POSTURES FOR HEALTH [By the practice of yogasanas] “the important endocrine system is controlled and regularized so that the correct quantities of the different hormones are secreted from all the glands in the body... The muscles and bones, nervous, glandular, respiratory, excretory and circulatory systems are coordinated so that they help one another. Asanas make the body flexible and able to adjust itself easily to changes of environment. The digestive functions are stimulated ... The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are brought into a state of balance so that the internal organs they control are neither overactive nor underactive... asanas maintain the ppyhysical body at optimum condition and encouragean unhealthy body to become healthy.” – Swami Satyananda Saraswati EasyDoPreCare & Reversal of Decay ™ © 2020 Nirankar S. Agarwal, Ph.D. No commercial use without express written permission 2 EXERCISES & YOGA POSTURES FOR HEALTH Introductory Notes About Asanas 1. Prior to practising asanas, a cool shower and a vigorous rub with a coarse towel helps the body to become supple by improving the blood circulation. But do not shower or bathe for 30 minutes after asanas. 2. Mornings are preferable for asanas. It is also easier to maintain regularity in the mornings, for myriad activities later in the day may create time crunch and lead to irregularity. 3. Let following times elapse before undertaking practice of asanas: 4 hours after full meal, 1 1/2 hour after snack, 1 hour after beverage. -

The-Forum-87Th-Edition-September

YOUNG YOGA INSTITUTE 87th Edition AUGUST 2016 Winnie Young Winnie & Mr Iyengar at a course in Mauritius A Word from the Principal 4 How Yoga and Massage can improve your body 6 Things we learned at La Verna 9 Health benefits of laughter 12 Walking – the most popular physical activity 14 Meditation 15 Is it too easy to become a Yoga teacher 16 Things Yoga teachers wish for 17 Astavakrasana 18 10 Things people get wrong about Yoga 19 Travel Plans 21 Last words of Steve Jobs 22 Time for a giggle 23 Why we love children 24 Versus 25 Recipes 26 Poetry 27 Birthdays 29 Welcome to the exponential age 30 MAILBOX NEWS 33 Tutorial Updates 38 KZN Yoga Dates 2016 40 National Executive Committee details 42 YYI Bank details on the inside back cover Dear Friends, Summer and autumn have now come and gone and as the song goes: “We had joy, we had fun, we had seasons in the sun” Luckily in our beautiful country South Africa, even in winter we are privileged to enjoy the life-giving sun I trust that like the sun, Yoga has kept you warm and enriched your life as it has mine. I am so happy that our March workshop was such a success – with 40 of our teachers and teachers-in-training attending. I am certain that all those who attended can agree with the saying “in life you get out proportionally to what you put in” and will continue to enjoy the benefits of their participation. In the same vein, I would like to encourage you all and especially if you have just joined as a member, to attend the August Seminar as well as the November retreat weekend, both held at the La Verna retreat centre on the banks of the Vaal River. -

The Challenge

10 day yoga challenge We’re inviting you all to join or 10 day yoga challenge and do it at your own pace! This challenge is about the journey - physi- cally, emotionally, and spiritually. This is a challenge to meet you where YOU are, not where you think you should be! It’s a chal- lenge that might surprise you of what you’re capable of. Most of all, it’s a challenge to just get close to feeling into your physical body to feel into the deeper subtle energies as you carry on with it. Share your challenge photos on Instagram with the hashtage #summersaltchallenge For each shared photo with the hashtag we will give 7 days of access to life-saving clean water to people in Africa as a part of our giv- ing back initiatives with B1G1 organization Bakasana 1 Crow pose Beginner version: Description a Malasana (angled squat) Crow pose is a great way to play with root and re- bound! The ground supports you to steady your bal- Intermediate version: ance as you begin to fly! b 1 leg lifted To start, come to angled squat. Add on by lifting one foot, and then the other. Keep the gaze forward Full version: (not down!) as you play with the transition to lift both feet! Keep the abdominals engaged and round c Bakasana (crow) through the upper back. B A C Parvritta Bakasana 2 Side crow pose Beginner version: Description a Prayer twist Side crow! One of our favorites. This pose defies gravity a bit. Allow the root energy to support you Intermediate version: as you twist and rise! b Hands placed down To start, come into prayer twist. -

Ashtanga Yoga Series

Bobbi Misiti 834 Market Street Lemoyne, PA 17043 717.443.1119 befityoga.com 1. Ashtanga Yoga Primary Series Surya Namaskar A 5x Surya Namaskar B 3x Standing Poses Padangusthasana / Padahastasana Utthita Trikonasana / Parivritta Trikonasana Utthita Parsvakonasana/Parivritta Parsvakonasan Prasarita Padottanasana A,B,C,D Parsvottanasana Utthita Hasta Padangusthasana Ardha Baddha Padmottanasana (Surya Namaskar into) Utkatasana (Surya Namaskar into) Virabhadrasana I and II Bobbi Misiti 834 Market Street Lemoyne, PA 17043 717.443.1119 befityoga.com 2. Seated poses - Yoga Chikitsa (yoga therapy) Paschimattanasana Purvattanasana Ardha Baddha Padma Paschimattanasana Triang Mukha Eka Pada Paschimattanasana Janu Sirsasana A,B,C Marichyasana A,B,C,D Navasana Bhujapidasana Kurmasana / Supta Kurmasana Garbha Pindasana / Kukkutasana Baddha Konasana Upavistha Konasana A,B Supta Konasana Supta Padangusthasana Ubhaya Padangusthasana Urdhva Mukha Paschimattanasana Setu Bandhasana Bobbi Misiti 834 Market Street Lemoyne, PA 17043 717.443.1119 befityoga.com 3. Urdhva Dhanurasana 3x Paschimattanasana 10 breaths Closing Sarvangasana Halasana Karnapidasana Urdhva Padmasana Pindasana Mathsyasana Uttana Padasana Sirsasana Baddha Padmasana Padmasana Utputhih Take Rest! Bobbi Misiti 834 Market Street Lemoyne, PA 17043 717.443.1119 befityoga.com 1. Intermediate Series - Nadi Shodhana (nerve cleansing) Surya Namaskar A 5x Surya Namaskar B 3x Standing Poses Padangusthasana / Padahastasana Utthita Trikonasana / Parivritta Trikonasana Utthita Parsvakonasana/Parivritta Parsvakonasan -

House of OM YTT Course Manual

1 2 3 4 Contents JOURNALING .............................................................................................. 13 WELCOME TO HOUSE OF OM ..................................................................... 16 HOUSE OF OM - Yoga School ...................................................................... 17 HOUSE OF OM - Founder Wissam Barakeh.................................................. 18 DEFINITION OF OM ..................................................................................... 20 DEFINITION OF YOGA .................................................................................. 22 HINDUISM (SANATHAN DHARMA) .............................................................. 24 HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF YOGA ................................................................... 25 Vedic and Pre-Classical Period ........................................................ 25 Classical Period .............................................................................. 26 Post-Classical Period ...................................................................... 27 Modern Period ............................................................................... 28 THE 4 TYPES OF YOGA ................................................................................. 30 Bhakti Yoga – Yoga of Devotion ...................................................... 30 Karma Yoga – Yoga of Selfless Service ............................................ 30 Jnana Yoga – Study of Philosophical works and the pursuit of knowledge .................................................................................... -

Arunachala! Thou Dost Root out the Ego of Tho$E Who Meditate on Thee in the Heart Oh Arunachafaf 3» Oh Undefiled, Abide Thou in My Heart So That

Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of tho$e who meditate on Thee in the heart Oh Arunachafaf 3» Oh Undefiled, abide Thou in my heart so that there may be everlasting (A QUARTERLY) joy, Arunachala ! " Arunachala ! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala ! " — The Marital Garland —The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1 of Letters, verse 52 Vol. 13 OCTOBER 1976 No. IV Publisher : CONTENTS Page T. N. Venkataraman, EDITORIAL: Yoga .... 203 President, Board of Trustees, Silence (Poem) — ' Nandi9 206 Sri Ramanasramam, Advaita and Worship — S. Sankaranarayanan 207 Tiruvannamalai. The Direct Sadhana— Dr. M. Sadasbiva Rao 211 Two Trading Songs (Poem) — 1 Kanji9 . 214 Person or Self ? — Norman Fraser . 215 Some Taoist Phrases — Murdoch Kirby . 216 Editorial Board: Sri Bhagavan and the Mother's Temple Sri Viswanatha Swami — Sadbu Arunachala . 218 Sri Ronald Rose The Vimalafiirti Nirdesa Sutra Prof. K. Swaminathan — Looking at Living Beings — Tr. Charles Luk . 219 Sri M. C. Subramanian The Right to Fight (A Japanese Story) Sri Ramamani Related by Tera Sasomote . 220 Sri T. P. Ramachandra Aiyer Love — (After Kabir) (Poem) — Colin Oliver 224 Non-attachment in the Small Things * — Marie B. Byles . 225 Managing Editor : " If Stones Could Speak ..." V. Ganesan, — Wei Wu Wei 227 Mother's Moksha — " A Devotee " . 228 Sri Ramanasramam, The English Mystic : Richard of St. Victor Tiruvannamalai. — Gladys Dehm . 230 The Joy of the Being (Poem)—Kavana . 231 Erase Face in Amazing Grace — Paul rePS 233 My Visit to Sri Ramanasramam — Sarada . 234 Annual Subscription : On Love (Poem) — Christmas Humphreys .