B8UB GREEN STATE IKQVER&TY Ubrart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

Widescreen Weekend 2010 Brochure (PDF)

52 widescreen weekend widescreen weekend 53 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (70MM) REMASTERING A WIDESCREEN CLASSIC: Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WINDJAMMER GETS A MAJOR FACELIFT Dir. Stanley Kubrick GB/USA 1968 149 mins plus intermission (U) Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WIDESCREEN Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Leonard Rossiter, Ed Presented by David Strohmaier and Randy Gitsch Bishop and Douglas Rain as Hal The producer and director team behind Cinerama Adventure offer WEEKEND During the stone age, a mysterious black monolith of alien origination a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how the Cinemiracle epic, influences the birth of intelligence amongst mankind. Thousands Now in its 17th year, the Widescreen Weekend Windjammer, was restored for High Definition. Several new and of years later scientists discover the monolith hidden on the moon continues to welcome all those fans of large format and innovative software restoration techniques were employed and the re- which subsequently lures them on a dangerous mission to Mars... widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, mastering and preservation process has been documented in HD video. Regarded as one of the milestones in science-fiction filmmaking, Cinerama and IMAX – and presents an array of past A brief question and answer session will follow this event. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey not only fascinated audiences classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. This event is enerously sponsored by Cinerama, Inc., all around the world but also left many puzzled during its initial A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. release. More than four decades later it has lost none of its impact. -

The Expulsion of Sir John Harvey from Virginia William Warner Moss

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1923 The expulsion of Sir John Harvey from Virginia William Warner Moss Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Moss, William Warner, "The expulsion of Sir John Harvey from Virginia" (1923). Honors Theses. Paper 258. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPULSION OF SIR JOHN HARVEY FROM VIRGINIA. WM. WARNER MOSS JIR. Submitted in competition for the J. Taylor Ellyson Medal in History University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia 1923 THE_ EXPULSION OF SIR JOH~T K.\.."qVEY When King James began to fear the preach ing of Sir Edwin Sandys and the meetings of the Virginia Company, believing that the seeds they sowed were too democratic, he felt sure that the dissolution or at least the royal control of the CompE>,ny was a necessity. He therefore attempted to interfere in the election of the treasurer but failed. Enraged, he commanded Captain Na.thaniel Butler to write a libel entltled "The Unmasking of Virginia", which held the Virginia Company responsible for all the evils in America. This served him little better than his interference, so, in April t623, he appointed a commission of "certayne obscure persons"', among them John Harvey and Samuel Matthews, whose duty it was to investigate the colony and furnish evi dence against the Company. -

Forty Years On: BBC Radio 4 Full Cast Dramatisation Free

FREE FORTY YEARS ON: BBC RADIO 4 FULL CAST DRAMATISATION PDF Alan Bennett | 1 pages | 07 Aug 2000 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9780563477952 | English | London, United Kingdom Advice | The Society of Authors This thrilling collection brings together three dramatisations and two original radio stories starring the Nottingham-based detective, all scripted by his creator, award-winning author John Harvey. Wasted Yearsand two incidents of violent robbery force Detective Inspector Resnick to relive painful memories of ten years earlier, when his marriage collapsed - and he arrested an armed criminal Starring Tom Wilkinson. Cutting Edge When a young doctor is attacked on a deserted hospital walkway, the clues seem to lead nowhere for DI Charlie Resnick. As he desperately searches for motives, another victim is assaulted Starring Tom Georgeson. But for Detective Inspector Charlie Resnick and his team, it is the start of a more sinister and deadly chain of events. Starring Philip Jackson. Cheryl While Detective Inspector Resnick pursues a gang of armed robbers, meals-on-wheels lady Cheryl takes the law into her own hands on behalf of an elderly client. It Forty Years on: BBC Radio 4 Full Cast Dramatisation long before their investigations collide Starring Keith Barron. Bird of Paradise Jerzy Grabianski is a high-class burglar with a passion for ornithology and British Impressionist paintings. Like DI Charlie Resnick, he has Polish roots, a firm sense of justice and a soft spot for the ladies - especially the energetic Sister Teresa Directed by David Hunter. Forty Years on: BBC Radio 4 Full Cast Dramatisation Ware, Abir Mukherjee, Lisa Jewell and more on the crime books that shaped them — and the genre itself. -

1 Introducing American Silent Film Comedy: Clowns, Conformity, Consumerism

Notes 1 Introducing American Silent Film Comedy: Clowns, Conformity, Consumerism 1. This speech has often been erroneously quoted (not least by Adam Curtis in his 2002 documentary The Century of the Self ) as ‘You have taken over the job of creating desire and transformed people into constantly moving happi- ness machines’ – a tremendously resonant phrase, but not one which actually appears in the text of Hoover’s speech. Spencer Howard of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library attributes the corrupted version to a mis-transcription several decades later. 2. The title of his 1947 essay. His key writings in the 1920s were Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923) and Propaganda (1928). 3. Of course, not all responded sympathetically to the film’s vicious racist message. The NAACP mounted a particularly effective campaign against the film, which was banned in several states and sparked mass protests in others. For the full story see Melvyn Stoke, D.W. Griffith’s ‘The Birth a Nation’, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. 4. CPI titles made in 1917/18 include America’s Answer, Under Four Flags and Pershing’s Crusaders – distributors who wanted the new Fairbanks or Pickford picture would be forced to take a CPI release as well. 2 A Convention of Crazy Bugs: Mack Sennett and the US’s Immigrant Unconscious 1. The temptation, here, is to regard Sennett’s name and the Keystone brand as being broadly synonymous, but one should remember that Sennett started off, first, as an actor and then, as a director at Biograph in 1909; the Key- stone Company was set up by Adam Kessel and Charles Baumann in 1912 (Sennett was never the owner). -

John Harvey Grant

"SKIPPER" JOHN HARVEY GRANT Ola May Grant Oldham "Skipper" John Harvey Grant was born in London, On reaching Jupiter,they struck camp on the north England,in 1862. His father was a Scot and his mother a side of the river near the inlet. The story goes that every native of Chester, England. The eldest of eight children, evening the boys brought out their musical instruments he grew up in the United Kingdom, living in England, and had a private concert. " Grandma Carlin;' a great Scotland and Ireland. He attended Albert College in homemaker who was not yet "Grandma;' lived on the Dublin, Ireland, and learned seamanship during holi South side of Jupiter River with her large brood. She days on a sailing vessel owned by the father of one of his heard the boys and one evening sent over to them a pot classmates. of baked beans and a loaf of homemade bread. That did The family immigrated to America when John was it! John settled for life on the Southeast Coast of Florida. nineteen years old, by sailing vessel, landing, first in He joined the life saving crew, bought land in Boston. Seeking a better climate, they came to Jackson Jupiter and started homesteading at Sugden (now Hobe ville, Florida, where they settled. John took to the sea. Sound). In 1892, he was a County Commissioner from Upon reaching his majority, he became a naturalized his district of old "giant" Dade County, and at one time, American citizen. when Juno was County seat.of Dade County, he was the One holiday, he and two other young chaps decided County Treasurer. -

Revolutionary Leaders of North Carolina

North Carolina State Normal & Industrial College Historical Publications Number 2 REVOLUTIONARY LEADERS OF NORTH CAROLINA BY R. D. W. CONNOR SECRETARY NORTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL COMMISSION Lecturer on North Carolina History, State Normal College Issued under the Direction of the Department of History W. C. JACKSON, EDITOR PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE 1916 PRESSES OF THE PETRIE COMPANY HIOH POINT. N. C I NORTH CAROLINA FROM 1765 TO 1790 INTRODUCTORY LECTURE Two periods in the history of the United States seem to me to stand out above all others in dramatic interest and historic importance. One is the decade from 1860 to 1870, the other is the quarter-century from 1765 to 1790. Of the two both in interest and importance precedence must be given to the latter. The former was a period of almost superhuman ef fort, achievement, and sacrifice for the preservation of the life of the nation, but it did not evolve any new social, political, or economic principles. Great prin ciples already thought out and established were saved from annihilation, and given a broader scope than ever before in the history of mankind, but no new idea or ideal was involved in the struggle. The ideas and ideals involved in the struggle of the sixties were those that had already been established during the quarter-century from 1765 to 1790. That epoch was a period of origins. Ideas and ideals of government developed in America then came into conflict with the ideas and ideals of Europe. Colonies founded on these new principles revolted against the old, threw off the yoke of their mother country, organized inde pendent states, and having achieved their independ ence, established a self-governing nation on the fed eral principle on a scale never before attempted in the history of the world. -

CORNFLAKES, GOD, and CIRCUMCISION: JOHN HARVEY KELLOGG and TRANSATLANTIC HEALTH REFORM by AUSTIN ELI LOIGNON DISSERTATION Submi

CORNFLAKES, GOD, AND CIRCUMCISION: JOHN HARVEY KELLOGG AND TRANSATLANTIC HEALTH REFORM by AUSTIN ELI LOIGNON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Steven G. Reinhardt, Supervising Professor Kathryne E. Beebe Robert B. Fairbanks Copyright © by Austin Eli Loignon 2019 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Cornflakes, God, and Circumcision: John Harvey Kellogg and Transatlantic Health Reform Austin Eli Loignon, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Steven G. Reinhardt The health reform movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth century impacted American and European societies in profound ways. These reforms, while usually represented in a national context, existed within a transatlantic framework that facilitated a multitude of exchanges and transfers. John Harvey Kellogg—surgeon, health reformer, and inventor of cornflakes— developed a transatlantic network of health reformers, medical practitioners, and scientists to improve his own reforms and establish new ones. Through intercultural transfer Kellogg borrowed, modified, and implemented European health reform practices at his Battle Creek Sanitarium in the United States. These transfers facilitated developments in reform movements such as vegetarianism, light therapy, sex, and eugenics. While health reform movements were a product of the modern world in which science and rationality were given preference, Kellogg infused his religious, Seventh-day Adventist beliefs into the reforms he practiced. In some cases health reform movements were previously semi-religious in nature and Kellogg merely accentuated an already present narrative of religious obligation for reform. These beliefs in salvific health reform centered around Kellogg’s desire to perfect the human body physically and spiritually in an attempt to make it fit for translation into heaven. -

The Bari Incident: Chemical Weapons and World War II

Activity: The Bari Incident: Chemical Weapons and World War II Guiding question: Was the American plan regarding the use of chemical weap- ons in response to an Axis strike during World War II justified? DEVELOPED BY AMANDA REID-COSSENTINO Grade Level(s): 9-12 Subject(s): Social Studies Cemetery Connection: Sicily-Rome American Cemetery Fallen Hero Connection: Corporal Robert S. Quirk Activity: The Bari Incident: Chemical Weapons and World War II 1 Overview Students will utilize resources from the American Battle Monuments Commission including “How did Poison Gas Change Warfare?” and information on Sicily-Rome American “I was very interested to Cemetery, as well as primary and secondary sources to learn about the Chemical Warfare Service as I examine the use of chemical warfare in World War II. They investigated the life of my will review the use of gas in World War I, learn about the Fallen Hero, Robert S. incident with the John Harvey at Bari, Italy, and complete a Quirk. In my research, I T-Chart illustrating pros and cons of using chemical weap- came across the terrible ons. Students will also ultimately take a personal stand on tragedy that unfolded at Bari the issue in a culminating writing assessment, a letter with Harbor, when a German air recommendations to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. attack released mustard gas that had been secretly stowed on the SS John Harvey.” Historical Context — Amanda Reid-Cossentino In 1943, the Allies’ focus was on the Mediterranean. Bari, Italy, Reid-Cossentino teaches at Garnet Valley a town of 200,000 on the Mediterranean Sea became an High School in Glen Mills, Pennsylvania. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H. -

Business on Television: Continuity, Change and Risk in the Development of Television’S ‘Business Entertainment Format’

Kelly, L. and Boyle, R. (2010) Business on television: continuity, change and risk in the development of television’s ‘business entertainment format’. Television and New Media . ISSN 1527-4764 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/32248/ Deposited on: 25 June 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Business on Television: Continuity, Change and Risk in the Development of Television’s ‘Business Entertainment Format’ Abstract: This article traces the evolution of what has become known as the business entertainment format on British television. Drawing on interviews with channel controllers, commissioners and producers from across the BBC, Channel 4 and the independent sector this research highlights a number of key individuals who have shaped the development of the business entertainment format and investigates some of the tensions that arise from combining entertainment values with more journalistic or educational approaches to factual television. While much work has looked at docusoaps and reality programming, this area of television output has remained largely unexamined by television scholars. The research argues that as the television industry has itself developed into a business, programme-makers have come to view themselves as [creative] entrepreneurs thus raising the issue of whether the development off-screen of a more commercial, competitive and entrepreneurial TV marketplace has impacted on the way the medium frames its onscreen engagement with business, entrepreneurship, risk and wealth creation. Keywords: BBC; Channel 4; television industry; factual entertainment; documentary; public service broadcasting, The Apprentice Word count: 8647 Business people [on television] were either dry boring people in suits, or shifty characters up to no good. -

Digital Program Booklet

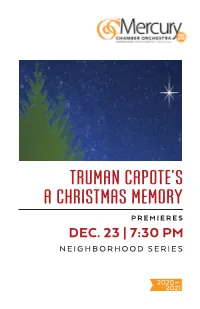

PROGRAM A CHRISTMAS MEMORY Truman Capote (1924-1984) DAVID RAINEY, ACTOR Pastorale from Concerto Grosso, Op. 6, No. 8 Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) Alternativo from Don Quixote Suite Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Miss Fogarty Christmas Cake C. Frank Horn (1851-1928) Show Me The Way To Go Home Irving King (n.d.) The Town Lay Hushed Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) O Tannenbaum Traditional Silent Night Franz Xaver Gruber (1787-1863) Adagio from Concerto Grosso, Op. 6, No. 8 Corelli THIS PERFORMANCE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PERMISSION OF THE TRUMAN CAPOTE LITERARY TRUST AND IS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY THE HOUSTON ENDOWMENT, THE BROWN FOUNDATION, THE CULLEN TRUST FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS, AND THE CITY OF HOUSTON THROUGH HOUSTON ARTS ALLIANCE. LIVE STREAMING OF THIS PERFORMANCE IS PRODUCED BY BEND PRODUCTIONS, INC. MERCURY SEASON 20/21 | 1 MERCURY MUSICIANS Jonathan Godfrey, Violin Andrés González, Violin Kathleen Carrington, Viola Sonya Matoussova, Cello Antoine Plante, Musical Arrangements Ben Doyle, Videography and Editing MERCURY SEASON 20/21 | 2 ARTIST PROFILE DAVID RAINEY, ACTOR David Rainey is a Houston-based theatre artist. As an actor, he’s been an Alley Theatre Resident Company Member since 2000, where he’s been seen as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, 4th Party Member in 1984, Shepherd in Winter’s Tale, Marcel in Murder on the Orient Express, Ravanche/Treville and others in The Three Musketeers, Reggie in Skeleton Crew, Albert/Kevin in Clybourne Park, Nasty Interesting Man/Lord of the Underworld in Eurydice, Sterling in Mauritius, and the title role in Othello. Nationally, he has performed for Theatre de la Jeune Lune, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Hartford Stage Company, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, the National Actors Theatre, the Guthrie Theatre, Joseph Papp Public Theatre, Manhattan Theatre Club, The Acting Company, New York Shakespeare Festival, Repertory Theatre of St.