The History of Australian-Israeli Relations Colin Rubenstein and Tzvi Fleischer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Australia Said NO! Fifteen Years Ago, the Australian People Turned Down the Menzies Govt's Bid to Shackle Democracy

„ By ERNIE CAMPBELL When Australia said NO! Fifteen years ago, the Australian people turned down the Menzies Govt's bid to shackle democracy. gE PT E M B E R . 22 is the 15th Anniversary of the defeat of the Menzies Government’s attempt, by referendum, to obtain power to suppress the Communist Party. Suppression of communism is a long-standing plank in the platform of the Liberal Party. The election of the Menzies Government in December 1949 coincided with America’s stepping-up of the “Cold War”. the Communist Party an unlawful association, to dissolve it, Chairmanship of Senator Joseph McCarthy, was engaged in an orgy of red-baiting, blackmail and intimidation. This was the situation when Menzies, soon after taking office, visited the United States to negotiate a big dollar loan. On his return from America, Menzies dramatically proclaimed that Australia had to prepare for war “within three years”. T o forestall resistance to the burdens and dangers involved in this, and behead the people’s movement of militant leadership, Menzies, in April 1950, introduced a Communist Party Dis solution Bill in the Federal Parliament. T h e Bill commenced with a series o f recitals accusing the Communist Party of advocating seizure of power by a minority through violence, intimidation and fraudulent practices, of being engaged in espionage activities, of promoting strikes for pur poses of sabotage and the like. Had there been one atom of truth in these charges, the Government possessed ample powers under the Commonwealth Crimes Act to launch an action against the Communist Party. -

Australia Is Awash with Political Memoir, but Only Some Will Survive the Flood

Australia is awash with political memoir, but only some will survive the... https://theconversation.com/australia-is-awash-with-political-memoir-b... Academic rigour, journalistic flair September 9, 2015 8.51am AEST For publishers, Australian political memoir or biography is likely to pay its own way, at the very least. AAP Image/Lukas Coch September 9, 2015 8.51am AEST Last year more than a dozen political memoirs were published in Australia. From Bob Author Carr’s Diary of a Foreign Minister to Greg Combet’s The Fights of My Life, from Rob Oakeshott’s The Independent Member for Lyne to Bob Brown’s Optimism, one could be forgiven for thinking Australia is a nation of political junkies. Jane Messer Or that we’re fascinated by the personalities, policies and procedures that shape our Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, political landscape. But are we really, and if not, why so many books? Macquarie University The deluge shows no signs of abating, with a similar number of titles expected this year. Already we’ve seen the release of Shadow Minister Chris Bowen’s The Money Men, reflections by Federal Labor members Mark Butler and Andrew Leigh, with former Victorian Labor leader John Brumby’s practical “lessons”, The Long Haul, in press. Liberals, once laggards in this genre, are stepping up in growing numbers. Federal Minister Christopher Pyne’s “hilarious” A Letter To My Children is out, and Peter Reith’s The Reith Papers is underway. Also in press is the genuinely unauthorised Born to Rule: the Unauthorised Biography of Malcolm Turnbull. -

Milton Friedman on the Wallaby Track

FEATURE MILTON FRIEDMAN ON THE WALLABY TRACK Milton Friedman and monetarism both visited Australia in the 1970s, writes William Coleman he recent death of Milton Friedman Australia, then, was besieged by ‘stagflation’. immediately produced a gusher of Which of the two ills of this condition—inflation obituaries, blog posts and editorials. or unemployment—deserved priority in treatment But among the rush of salutes was a matter of sharp disagreement. But on and memorials, one could not certain aspects of the policy problem there existed Tfind any appreciation of Friedman’s part in the a consensus; that the inflation Australia was Australian scene. This is surprising: his extensive experiencing was cost-push in nature, and (with an travels provided several quirky intersections with almost equal unanimity) that some sort of incomes Australian public life, and his ideas had—for policy would be a key part of its remedy. This was a period of time—a decisive influence on the certainly a politically bipartisan view, supported Commonwealth’s monetary policy. by both the Labor Party and the Liberal Party Milton Friedman visited Australia four times: during the 1974 election campaign.2 The reach 1975, 1981, and very briefly in 1994 and 2005. of this consensus is illustrated in its sway over the On none of these trips did he come to visit Institute of Public Affairs. The IPA was almost shrill Australian academia, or to play any formal policy in its advocacy of fighting inflation first. But the advice role. Instead his first visit was initiated and IPA’s anti-inflation policy, as outlined in the ‘10 organised by Maurice Newman, then of the Sydney point plan’ it issued in July 1973, was perfectly stockbroking firm Constable and Bain (later neo-Keynesian. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

Annual Report 2014 – 2015

Annual Report 2014 – 2015 JewishCare’s Mission Support and strengthen the resilience and independence of community members in need BOARD ALLAN BOYD VIDOR LAWRENCE MYERS DR JEFFREY LIONEL President Honorary Treasurer ENGELMAN SHIRLI KIRSCHNER ALLAN VIDOR LAWRENCE MYERS Auditor and a Registered member of the Australian Tax Agent. Lawrence holds Jewish Holocaust Survivors Appointed as Director on Appointed as Director on several board position’s and Descendants, 29 June 2006. 26 June 2008. with private and not where his father is a past Born 29/03/1963 in Born on 17/04/1974 in for profit organisations. President. Sydney, Australia. Cape Town South Africa. Lawrence is also a SHIRLI KIRSCHNER Allan is the Managing Lawrence is the Managing non-executive director of Appointed as Director on Director of the Toga Group Director and founder of Breville Group Limited, 20 March 2013 of Companies, a property MBP Advisory Pty. Limited listed on the Australian development, construction, - a prominent high end Stock Exchange. Born 05/12/1964 in Tel investment and hospitality Sydney firm - which he DR JEFFREY Aviv Israel management group. established in 1998. Prior ENGELMAN Shirli has a Bachelor of He graduated from the to that, Lawrence spent Appointed as Director on Arts (Psychology) and Law University of NSW with 6 years in small and large 24 November 2005. (UNSW) and is a Nationally Bachelor of Commerce Chartered Accounting accredited mediator. and Laws degrees in 1985 firms. His client base Born 08/11/1962 in and was admitted as a spans a broad range of Sydney, Australia. She worked as a lawyer for Solicitor of the Supreme industries and activities six years before founding Jeffrey is a Court of NSW in 1986. -

Paul Ormonde's Audio Archive About Jim Cairns Melinda Barrie

Giving voice to Melbourne’s radical past Paul Ormonde’s audio archive about Jim Cairns Melinda Barrie University of Melbourne Archives (UMA) has recently Melbourne economic historian and federal politician Jim digitised and catalogued journalist Paul Ormonde’s Cairns’.4 Greer’s respect for Cairns’ contribution to social audio archive of his interviews with ALP politician Jim and cultural life in Australia is further corroborated in her Cairns (1914–2003).1 It contains recordings with Cairns, speech at the launch of Protest!, in which she expressed and various media broadcasts that Ormonde used when her concern about not finding any trace of Cairns at the writing his biography of Cairns, A foolish passionate university, and asked about the whereabouts of his archive: man.2 It also serves as an oral account of the Australian ‘I have looked all over the place and the name brings up Labor Party’s time in office in the 1970s after 23 years in nothing … you can’t afford to forget him’.5 Fortunately, opposition.3 Paul Ormonde offered to donate his collection of taped This article describes how Ormonde’s collection was interviews with Cairns not long after Greer’s speech. acquired and the role it has played in the development During his long and notable career in journalism, of UMA’s audiovisual (AV) collection management Ormonde (b. 1931) worked in both print and broadcast procedures. It also provides an overview of the media, including the Daily Telegraph, Sun News Pictorial Miegunyah-funded AV audit project (2012–15), which and Radio Australia. A member of the Australian Labor established the foundation for the care and safeguarding Party at the time of the party split in 1955, he was directly of UMA’s AV collections. -

The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Delivered on the 4Th of November, 2004 at the Joan B

Hanan Ashrawi, Ph.D. Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Delivered on the 4th of November, 2004 at the joan b. kroc institute for peace & justice University of San Diego San Diego, California Hanan Ashrawi, Ph.D. Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Edited by Emiko Noma CONTENTS Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice 4 Joan B. Kroc Distinguished Lecture Series 6 Biography of Hanan Ashwari, Ph.D. 8 Interview with Dr. Hanan Ashwari by Dr. Joyce Neu 10 Introduction by Dr. Joyce Neu 22 Lecture - Concept, Context and Process in Peacemaking: 25 The Palestinian-Israeli Experience Questions and Answers 48 Related Resources 60 About the University of San Diego 64 Photo: Architectural Photography, Inc. Photography, Photo: Architectural 3 JOAN B. KROC INSTITUTE FOR PEACE & JUSTICE The mission of the Joan B. peacemaking, and allow time for reflection on their work. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice (IPJ) is to foster peace, cultivate A Master’s Program in Peace & Justice Studies trains future leaders in justice and create a safer world. the field and will be expanded into the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, Through education, research and supported by a $50 million endowment from the estate of Mrs. Kroc. peacemaking activities, the IPJ offers programs that advance scholarship WorldLink, a year-round educational program for high school students and practice in conflict resolution from San Diego and Baja California connects youth to global affairs. and human rights. The Institute for Peace & Justice, located at the Country programs, such as the Nepal project, offer wide-ranging conflict University of San Diego, draws assessments, mediation and conflict resolution training workshops. -

Peace, Propaganda, and the Promised Land

1 MEDIA EDUCATION F O U N D A T I O N 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org Peace, Propaganda & the Promised Land U.S. Media & the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Transcript (News clips) Narrator: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dominates American news coverage of International issues. Given the news coverage is America's main source of information on the conflict, it becomes important to examine the stories the news media are telling us, and to ask the question, Does the news reflect the reality on the ground? (News clips) Prof. Noam Chomsky: The West Bank and the Gaza strip are under a military occupation. It's the longest military occupation in modern history. It's entering its 35th year. It's a harsh and brutal military occupation. It's extremely violent. All the time. Life is being made unlivable by the population. Gila Svirsky: We have what is now quite an oppressive regime in the occupied territories. Israeli's are lording it over Palestinians, usurping their territory, demolishing their homes, exerting a very severe form of military rule in order to remain there. And on the other hand, Palestinians are lashing back trying to throw off the yoke of oppression from the Israelis. Alisa Solomon: I spent a day traveling around Gaza with a man named Jabra Washa, who's from the Palestinian Center for Human Rights and he described the situation as complete economic and social suffocation. There's no economy, the unemployment is over 60% now. Crops can't move. -

THE TRANSFORMATIVE ROLES of PALESTINIAN WOMEN in the ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT by MEGAN BA

AN ARMY OF ROSES FOR WAGING PEACE: THE TRANSFORMATIVE ROLES OF PALESTINIAN WOMEN IN THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT by MEGAN BAILEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 An Abstract of the Thesis of Megan Bailey for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken June 2014 Title: An Army of Roses for Waging Peace: The Transformative Roles of Palestinian Women in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Approved: __'_J ~-= - ....;::-~-'--J,,;...;_.....:~~:==:......._.,.,~-==~------ Professor FrederickS. Colby This thesis examines the different public roles Palestinian women have assumed during the contemporary history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The thesis uses the problematic juxtaposition between the high public visibility of female militants and relatively low visibility of female political figures as a basis for investigating individual Palestinian women and women's groups that have participated in the Palestinian public sphere from before the first Intifada to the present. The thesis addresses the current state of Palestine's political structure, how international sources of support for enhancing women's political participation might be implemented, and internal barriers Palestinian women face in becoming politically active and gaining leadership roles. It draws the conclusions that while Palestinian women do participate in the political sphere, greater cohesion between existing women's groups and internal support from society and the political system is needed before the number of women in leadership positions can be increased; and that inclusion of women is a necessary component ofbeing able to move forward in peace negotiations. -

The Vultures Will Be Hovering Again Soon Enough, As Bill Shorten Begins to Stumble Date September 21, 2015 - 5:58AM

The vultures will be hovering again soon enough, as Bill Shorten begins to stumble Date September 21, 2015 - 5:58AM Paul Sheehan Sydney Morning Herald columnist Disability deserves its own ministry: Shorten Opposition leader Bill Shorten says he is disappointed Malcolm Turnbull's new ministry does not feature a minister for disability. Courtesy ABC News 24. It is only natural that the vultures will grow hungry again soon. They have become accustomed to kings becoming carrion. In the past 20 years Paul Keating, Kim Beazley, Simon Crean, Mark Latham, Beazley again, John Howard, Brendan Nelson, Malcolm Turnbull, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Rudd again, and now Tony Abbott have all been felled, a procession of change, on average, every 20 months, for 20 years. It shows no sign of slowing. In this context, the Canning by-election could have been called the Cunning by- election. It gave a clear, vindicating victory for Malcolm Turnbull's brazen, lightning coup. So now the vultures will soon be hovering over the obvious loser, Bill Shorten, who made a serious blunder last week that puts him on carrion watch. Having hovered over Abbott for months, the vultures will be riding the political thermals and circling in the sky, watching for Shorten to falter. He just became much more vulnerable. He has never been popular in the opinion polls. He has rarely been impressive in parliament. He was especially unimpressive in the three sitting days leading up to the Canning by-election. On Tuesday, in his first question to the new Prime Minister, Shorten finished -

Digital Edition

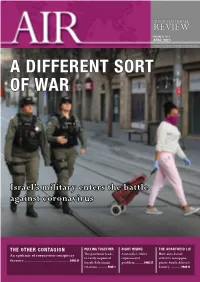

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

Strategic Thought and Security Preoccupations in Australia Coral Bell

1 Strategic Thought and Security Preoccupations in Australia Coral Bell This essay was previously published in the 40th anniversary edition. It is reprinted here in its near original format. The other authors in this volume have provided such authoritative accounts of the processes that led to the foundation, 40 years ago, of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre (SDSC), and its development since, that there is nothing that I can add on that score. Instead, this essay is devoted to exploring what might be called Australia’s strategic culture: the set of intellectual and political assumptions that led to our security anxieties and strategic dilemmas having been perceived and defined as they have been. There will also be some consideration of the outside influences on perceptions in Australia, and of such ‘side streams’ of thought as have run somewhat counter to the mainstream, but have been represented within SDSC. Long before Australians constituted themselves as a nation, they developed a strong sense of their potential insecurity, and the inkling of a strategy to cope with that problem. That strategy was what Australia’s most powerful and influential prime minister, Robert Menzies, was (much later) to call the cultivation of ‘great and powerful friends’. Initially that assumption was so automatic as hardly needing to be defined. Britain was the most powerful of the dominant players 1 A NatiONAL ASSeT in world politics for almost all the 19th century, and Australia was its colony. The ascendancy of the Royal Navy in the sea lines between them provided adequate protection, and Australia’s role was merely to provide expeditionary forces (starting with the Sudan War of 1885) for the campaigns in which they might be strategically useful.