Baltic States: Squashed Hopes in the Realm of Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

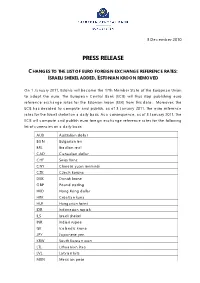

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. 712 April 2017 Asian Development Bank Institute Zsolt Darvas is senior fellow at Bruegel and senior research Fellow at the Corvinus University of Budapest. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Darvas, Z. 2017. Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: The Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 712. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/regional-and-global-financial-safety-nets Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for the Conference on Global Shocks and the New Global/Regional Financial Architecture, organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute and S. -

Baltic Monetary Regimes in the Xxist Century

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Viksnins, George J. Article — Digitized Version Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Viksnins, George J. (2000) : Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 35, Iss. 5, pp. 213-218 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/40777 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu EU ENLARGEMENT member states, the candidates should expect the dangers of inaction are even greater because the enlargement to be in a state of fluidity. existing member states may use their veto on • Second, the fact that uncertainty cannot be accession of new members to protect their broader interests. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013) 540 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area 1. INTRODUCTION Since the adoption of the euro by Estonia on 1 January 2011, the euro area consists of seventeen EU Member States. Among the remaining eleven Member States, nine Member States are expected to adopt the euro once the necessary conditions are fulfilled. Denmark and the United Kingdom have a special "opt-out"-status and are not committed to adopt the euro. This report assesses the state of play of the practical preparations for introducing the euro in Latvia and evaluates the progress made in preparing the changeover related communication campaign. Following the Council decision from 9 July 2013 concluding that the necessary conditions for euro adoption are fulfilled, Latvia will adopt the euro on 1 January 2014 ("€- day"). The conversion rate between the Latvian lats and the euro has been irrevocably fixed at 0.702804 Latvian lats to one euro. 2. STATE OF PLAY OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE CHANGEOVER IN LATVIA Latvia will be the sixth of the group of Member States which joined the EU in 2004 to adopt the euro. Latvia's original target date of 1 January 2008 foreseen in the Action Plan for Implementation of the Single European Currency of 1 November 2005 was subsequently reconsidered. -

Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia

ISSN 1725-3217 Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY 3|2013 Economic and Financial Affairs The European Economy series contains important reports and communications from the Commission to the Council and the Parliament on the economic situation and developments, such as the European economic forecasts and the Public finances in EMU report. Unless otherwise indicated the texts are published under the responsibility of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission to which enquiries should be addressed. Legal notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this publication, or for any errors which, despite careful preparation and checking, may appear. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN 978-92-79-28535-6 doi: 10.2765/40058 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY European Economy N° 3/2013 ABBREVIATIONS LV Latvia EA Euro area EU-27 European Union, 27 Member States EU-25 European Union, 25 Member States before 2007 (i.e. EU-27 excl. BG and RO) EU-15 European Union, 15 Member States before 2004 EUR Euro ECU European currency unit LVL Latvian lats USD US dollar SDR Special Drawing Rights AMR Alert Mechanism Report BoL Bank of Latvia BoP Balance of Payments -

As Parex Banka

AS PAREX BANKA ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2008 TOGETHER WITH INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT Table of Contents Management Report 3 Management of the Bank 7 Statement of Responsibility of the Management 8 Financial Statements: Statements of Income 9 Balance Sheets 10 Statements of Changes in Equity 11 Statements of Cash Flows 13 Notes 14 Auditors’ Report 80 AS Parex banka Smilšu 3, Riga, LV-1522, Latvia Phone: (371) 67010 000 Facsimile: (371) 67010 001 Registration number: 40003074590 2 AS Parex banka Management Report The year 2008 brought major change to Parex banka , including substantial changes in shareholders structure and the management of the bank in the last months of 2008. This report has been prepared by the new Management Board and Supervisory Council of the Bank and they are committed to leading the Bank into a new phase of development. Financial crisis and its implications on Parex banka The year of 2008 brought unprecedented challenges for the financial sector both in Latvia and worldwide. The global credit crunch, starting in the United States of America, caused a chain reaction all over the world and intensified the economic difficulties in Latvia. The financial sector in Latvia has been affected in a number of ways, mostly through reduced availability of funding and liquidity from international financial markets, a weakening economy and the resulting decline of asset quality. The crisis has necessitated the adoption of new approaches to the financial sector and has led to a thorough reconsideration of its practices. Parex banka itself experienced a severe impact from the crisis of 2008. -

Enforcement of Scc and Russian Arbitration Awards in the United States Courts: an Overview

Stockholm Arbitration Report, Volume 2003:2 ENFORCEMENT OF SCC AND RUSSIAN ARBITRATION AWARDS IN THE UNITED STATES COURTS: AN OVERVIEW Alexander S. Vesselinovitch* Several published decisions by U.S. federal and state courts have addressed SCC and Russian arbitration awards and proceedings. Some of these decisions, which came after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, strongly suggest that a Russian arbitration award will be enforced against a U.S. party or citizen by a U.S. court. Moreover, the published decisions by U.S. courts lend support to the enforcement by a U.S. court of an arbitration award rendered by the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (“SCC”) against a U.S. party. 1. Policy of New York Convention Favors Enforcement The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 1958, commonly called the “New York Convention,” was adopted with several reservations by the United States in 1970. The enabling legislation incorporated the New York Convention into Chapter Two of the United States Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. §§ 201-208. * Katten Muchin Zavis Rosenman, 525 West Monroe Street, Suite 1600, Chicago, Illinois 60661, (Telephone) 312-902-5660, (Facsimile) 312-577-4755, E-Mail: [email protected]. © 2003 Juris Publishing, Inc. Reprinted with Permission. All rights reserved. 37 Sweden, Russia, and the United States are signatories and contracting parties to the New York Convention. Moreover, Russian courts have applied provisions of the New York Convention under Russia’s Civil Code. Several commentators have already observed that the prospects for the enforcement of an SCC Institute award are very favorable in the courts of another party to the New York Convention.1 Because Sweden has generous rules regarding the validity of arbitration agreements, an arbitral award rendered on the basis of such an agreement will rarely be refused enforcement.2 Nevertheless, no published decision by a U.S. -

The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications

The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications Dick K. Nanto, Coordinator Specialist in Industry and Trade July 2, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34742 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications Summary The world has entered a global recession that is causing widespread business contraction, increases in unemployment, and shrinking government revenues. Some of the largest and most venerable banks, investment houses, and insurance companies have either declared bankruptcy or have had to be rescued financially. Nearly all industrialized countries and many emerging and developing nations have announced economic stimulus and/or financial sector rescue packages, such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). Several countries have resorted to borrowing from the International Monetary Fund as a last resort. The crisis has exposed fundamental weaknesses in financial systems worldwide, demonstrated how interconnected and interdependent economies are today, and has posed vexing policy dilemmas. The process for coping with the crisis by countries across the globe has been manifest in four basic phases. The first has been intervention to contain the contagion and restore confidence in the system. This has required extraordinary measures both in scope, cost, and extent of government reach. The second has been coping with the secondary effects of the crisis, particularly the global recession and flight of capital from countries in emerging markets and elsewhere that have been affected by the crisis. The third phase of this process is to make changes in the financial system to reduce risk and prevent future crises. -

The Baltic States and the Crisis of 2008-2011 Rainer Kattel and Ringa

The Baltic States and the Crisis of 2008-2011 Rainer Kattel and Ringa Raudla1 This essay explores how the Baltic republics responded to the crisis of 2008–2011.We argue that while there are significant differences in how the Baltic economies responded to the crisis, these responses not only remain within the neo-liberal policy paradigm characteristic of the region from the early 1990s, but that the crisis radicalised Baltic economies and particularly their fiscal stance. We show that there are a number of unique features in all three Baltic republics’ political economies that made such a radicalisation possible. However, these unique features make it almost impossible for the Baltic experience to be replicable anywhere else in Europe. 1. Introduction Europe, and the rest of the developed world along with it, seems to be mired in a debate over whether austerity brings growth or not. While there seem to be less and less candidates for actual European cases where fiscal retrenchment resulted in economic recovery and growth, the Baltic states persistently attempt to claim that austerity works. All three countries were painfully hit by the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 and topped the global charts in GDP contraction; all three responded to the crisis by adopting a series of austerity measures. In 2010, the Baltic states started to recover and recorded GDP growth between 5.5% and 7.6% in 2011. In the light of such temporal sequences of events, there has been a temptation in the policy circles both inside the Baltic states but also internationally to draw a causal conclusion and to claim that it was the austerity that led to growth. -

Exchange Rate Statistics January 2013

Exchange rate statistics January 2013 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2013 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is published by the Deutsche Bundes bank, Frankfurt am Tel +49 69 9566-0 Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. or +49 69 9566 8604 It is available to interested parties free of charge. Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, http://www.bundesbank.de can be found in the follow ing supplements. Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Banking statistics monthly Capital market statistics monthly The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- Balance of payments statistics monthly ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in Seasonally adjusted printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an business statistics monthly updated monthly edition in German and in English on its website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Selected updated statistics are also available on the website. version is the sole authoritative text. Additionally, a CD-ROM containing roughly 40,000 pub- lished Bundesbank time series, which is updated monthly, ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) may be obtained for a fee from the Bundesbank‘s Statistical Information Systems and Mathematical Methods Division Cut-off date: 14 January 2013. or downloaded from the Bundesbank‘s ExtraNet platform. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2013 3 Contents I Euro-area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevocable euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union ................................................................. -

Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Suggested Routing: Authorization Contact, Clearing Contact, Principal Contact, Settlement Contact

Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Suggested routing: Authorization Contact, Clearing Contact, Principal Contact, Settlement contact Topic(s): Currency, Settlement Applies to: P Acquirers P Issuers P Processors Summary: On 9 July 2013, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Latvia announced that the country of Latvia will adopt the euro as its official currency effective 1 January 2014. The Bank of Latvia also announced that all payments and transactions made by financial institutions in Latvia should be conducted in euros beginning at 00:00 local time on 1 January 2014. Action Indicator: M Mandate Effective Date: 1 January 2014 Overview As published in Global Operations Bulletin No. 8, 1 August 2013 and announced by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Latvia on 9 July 2013, the country of Latvia will adopt the euro as its official currency effective 00:00 local Latvian time on 1 January 2014. The European Central Bank announced that the irrevocable fixed exchange rate is set at 0.702804 Latvian lats to the euro. The Bank of Latvia has also announced that upon adoption of the euro, all payments and transactions made by financial institutions in Latvia should be conducted in euros. This article clarifies certain dates regarding support of the euro in Latvia. Customer Impact MasterCard currently supports the euro currency alphanumeric currency code EUR/978. MasterCard will continue to support the Latvian lats—alphanumeric currency code LVL/428—after Latvia adopts the euro for certain financial transactions as noted in the following paragraphs. Revised Dates to Support the Adoption of the Euro in Latvia Global Operations Bulletin No. -

Impacts of IMF Policies on National Education Budgets and Teachers

Impacts of IMF Policies on National Education Budgets and Teachers Exploring Possible Alternatives and Strategies for Advocacy By Rick Rowden Education International Research Institute June 2011 1 CONTENTS Introduction . 3 Part 1 Critique of IMF Policies . 4 1.1 Background: The Overall Development Model . 4 1.2 “Poverty Reduction” as Development . 5 1.3 “Poverty Reduction” is not Development . 9 1.4 How IMF fiscal and monetary policies undermine education systems . 11 1.5 Advocates for education must become advocates for a new development model . 15 1.6 The Role of the IMF in the Recent Global Economic Crisis . 16 Part 2 Alternative Macroeconomic Policies . 19 2.1 Some Basic Differences between Economies of Developing countries and Industrialized Countries 19 2.2 Degree of Progressivity in the Tax Structure . 21 2.3 Expanding the Tax Base . 21 2.4 Efforts to bring in the informal sector firms into the tax‐paying formal sector . 22 2.5 Justification for Short‐Term Deficit Spending in Crises and Recessions . 22 2.6 Justification for Long‐Term Deficit Financing for Development . 23 2.7 Need for Reorganizing Budget Accounting . 23 2.8 When absolutely necessary, deficit‐reduction must be undertaken with utmost care . 24 2.9 The Main Problem with IMF Monetary Policy . 24 2.10 Alternatives to IMF Monetary Policy . 25 2.11 Financial Sector Regulation . 26 2.12 UNDESA Policy Notes on Financial Policies . 26 2.13 Industrial Policy . 26 Part 3 Case Studies . 29 JAMAICA . 29 3.1 Background on Economic Situation in Jamaica . 29 3.2 Current IMF Program for Jamaica .