Hebcal 5778H.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stolen Talmud

History of Jewish Publishing, Week 3: Modern Forgeries R' Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] Pseudepigraphy 1. Avot 6:6 One who makes a statement in the name of its original source brings redemption to the world, as Esther 2:22 says, "And Esther told the king, in the name of Mordechai." 2. Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat 6:1 Rabbi Avahu cited Rabbi Yochanan: One may teach his daughter Greek; this is ornamental for her. Shimon bar Abba heard this and said, "Because Rabbi Avahu wants to teach his daughter Greek, he hung this upon Rabbi Yochanan." Rabbi Avahu heard this and said, "May terrible things happen to me, if I did not hear this from Rabbi Yochanan!" 3. Talmud, Pesachim 112a If you wish to be strangled, hang yourself by a tall tree. Besamim Rosh 4. Responsa of Rabbeinu Asher ("Rosh") 55:9 The wisdom of philosophy and the wisdom of Torah and its laws do not follow the same path. The wisdom of Torah is a tradition received by Moses from Sinai, and the scholar will analyze it via the methods assigned for its analysis, comparing one matter and another. Even where this does not match natural wisdom, we follow the tradition. Philosophical wisdom is natural, with great scholars who established natural arguments, and in their great wisdom they dug deeper and corrupted (Hosea 9:9) and needed to deny the Torah of Moses, for the Torah is entirely unnatural and revelatory. Regarding this it is stated, 'You shall be pure with HaShem your Gd,' meaning that even if something is outside of natural logic, you should not doubt the received tradition, but walk before Him in purity. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Why Did Moses Break the Tablets (Ekev)

Thu 6 Aug 2020 / 16 Av 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Ekev Why Did Moses Break the Tablets? Introduction In this week's portion, Ekev, Moses recounts to the Israelites how he broke the first set of tablets of the Law once he saw that they had engaged in idolatry by building and worshiping a golden calf: And I saw, and behold, you had sinned against the Lord, your God. You had made yourselves a molten calf. You had deviated quickly from the way which the Lord had commanded you. So I gripped the two tablets, flung them away with both my hands, and smashed them before your eyes. [Deut. 9:16-17] This parallels the account in Exodus: As soon as Moses came near the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, he became enraged; and he hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain. [Exodus 32:19] Why did he do that? What purpose did it accomplish? -Wasn’t it an affront to God, since the tablets were holy? -Didn't it shatter the authority of the very commandments that told the Israelites not to worship idols? -Was it just a spontaneous reaction, a public display of anger, a temper tantrum? Did Moses just forget himself? -Why didn’t he just return them to God, or at least get God’s approval before smashing them? Yet he was not admonished! Six explanations in the Sources 1-Because God told him to do it 1 The Talmud reports that four prominent rabbis said that God told Moses to break the tablets. -

Who's to Blame?

ª#…π Volume 4. Issue 49 . Who’s to blame? In the last mishna of the first perek of Horayot, the Torah is telling us that Beit-Din also has a we read of a dispute between three of the great second roll as the Beit-Din of the people as a Tannaim of the mishna: Rabbi Meir, Rabbi whole. Beit-Din and the nation are connected not Yehuda and Rabbi Shimon. The gemara goes into simply because the people are made up of those a lengthy explanation of their respective individuals the Beit-Din is responsible for, but understandings of the halachos of Par He’alem rather because the nation forms an entity which Davar Shel Tzibbur, but investigating these enjoys a special relationship with Beit-Din. As understandings to their absolute conclusions is such, the Beit-Din is responsible for actions the beyond the scope of this small Dvar Torah. nation does due to its rulings. In short, according Instead, let us look at one single point of dispute to Rabbi Meir this relationship makes it as if Beit and try to touch upon the deeper meaning of what Din were the ones who sinned. they are saying. Rabbi Yehuda’s view is different: Whoever heard The mishna tells us that the three argue regarding of a case where one person has an erroneous who brings the sacrifice in such a case when the notion, the other sins through misconception, and Beit-Din gives an erroneous ruling and the people they are liable? Usually the mistaken notion and (majority, at least) follow that ruling. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Sukkot Potpourri

Sukkot Potpourri [note: This document was created from a selection of uncited study handouts and academic texts that were freely quoted and organized only for discussion purposes.] Byron Kolitz 30 September 2020; 12 Tishrei 5781 Midrash Tehillim 17, Part 5 - Why is Sukkot so soon after Yom Kippur? (Also referred to as Midrash Shocher Tov; its beginning words are from Proverbs 11:27. The work is known since the 11th century; it covers only Psalms 1-118.) In your right hand there are pleasures (Tehillim 16:11). What is meant by the word pleasures? Rabbi Abin taught, it refers to the myrtle, the palm-branch, and the willow which give pleasure. These are held in the right hand, for according to the rabbis, the festive wreath (lulav) should be held in the right hand, and the citron in the left. What kind of victory is meant in the phrase? As it appears in the Aramaic Bible: ‘the sweetness of the victory of your right hand’. That kind of victory is one in which the victor receives a wreath. For according to the custom of the world, when two charioteers race in the hippodrome, which of them receives a wreath? The victor. On Rosh Hashanah all the people of the world come forth like contestants on parade and pass before G-d; the children of Israel among all the people of the world also pass before Him. Then, the guardian angels of the nations of the world declare: ‘We were victorious, and in the judgment will be found righteous.’ But actually no one knows who was victorious, whether the children of Israel or the nations of the world were victorious. -

Texts and Traditions

Texts and Traditions A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism COMPILED, EDITED, AND INTRODUCED BY Lawrence H. Schiffinan KTAV PUBLISHING HOUSE, INC. 1998 518 Texts and Traditions Chapter 10: Mishnah: The New Scripture 519 tory only those observances which are in the written word, but need not ancient customs. For customs are unwritten laws, the decisions approved observe those which are derived from the tradition of our forefathers. by ~en of old, not inscribed on monuments nor on leaves of paper which the moth destroys, but on the souls of those who are partners in 10.2.2 Philo, The Special Laws IV, 143-150: 40 the. same c~tizenship. For children ought to inherit from their parents, Written and Unwritten Law besides their property, ancestral customs which they were reared in and Philo discusses both the immortality of the written law} and the obligation have lived with even from the cradle, and not despise them because they of observing the customs, the unwritten law. Although the Greek world had a h~ve been handed down without written record. Praise cannot be duly concept of unwritten law, Philo's view is clearly informed by Jewish tradition given to one who obeys the written laws, since he acts under the admoni and by the Pharisaic concept of tradition. tion of restraint ~nd the fear of punishment. But he who faithfully observes the unwritten deserves commendation, since the virtue which he ~ displays is freely willed. Another most admirable injunction is that nothing should be added or 10.2.3 Mark 7: The Pharisees and Purity taken away,41 but all the laws originally ordained should be kept unaltered just as. -

New Contradictions Between the Oral Law and the Written Torah 222

5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il Science and faith main New Contradictions Between The Oral Law And The Written Torah 222 Contradictions in the Oral Law Talmud Mishneh Halacha 1/68 /מדע-אמונה/-101סתירות-מביכות-בין-התורה-שבעל-פה-לתורה/https://igod.co.il 5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il You may be surprised to hear this - but the concept of "Oral Law" does not appear anywhere in the Bible! In truth, such a "Oral Law" is not mentioned at all by any of the prophets, kings, or writers in the entire Bible. Nevertheless, the Rabbis believe that Moses was given the Oral Torah at Sinai, which gives them the power, authority and control over the people of Israel. For example, Rabbi Shlomo Ben Eliyahu writes, "All the interpretations we interpret were given to Moses at Sinai." They believe that the Oral Torah is "the words of the living God". Therefore, we should expect that there will be no contradictions between the written Torah and the Oral Torah, if such was truly given by God. But there are indeed thousands of contradictions between the Talmud ("the Oral Law") and the Bible (Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim). According to this, it is not possible that Rabbinic law is from God. The following is a shortened list of 222 contradictions that have been resurrected from the depths of the ocean of Rabbinic literature. (In addition - see a list of very .( embarrassing contradictions between the Talmud and science . -

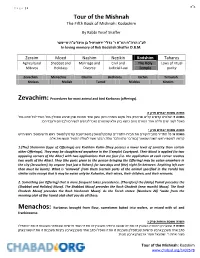

Tour of the Mishnah the Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim

ב"ה P a g e | 1 Tour of the Mishnah The Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim By Rabbi Yosef Shaffer לע"נ הרה"ח הוו"ח ר' גדלי' ירחמיא-ל בן מיכל ע"ה שייפער In loving memory of Reb Gedaliah Shaffer O.B.M. Zeraim Moed Nashim Nezikin Kodshim Taharos Agricultural Shabbat and Marriage and Civil and The Holy Laws of ritual Mitzvos Holidays Divorce Judicial Law Temple purity Zevachim Menachos Chullin Bechoros Erchin Temurah Kreisos Meilah Tamid Middos Kinnim Zevachim: Procedures for most animal and bird Korbanos (offerings). משנה מסכת זבחים פרק ה משנה ז: שלמים קדשים קלים שחיטתן בכל מקום בעזרה ודמן טעון שתי מתנות שהן ארבע ונאכלין בכל העיר לכל אדם בכל מאכל לשני ימים ולילה אחד המורם מהם כיוצא בהן אלא שהמורם נאכל לכהנים לנשיהם ולבניהם ולעבדיהם: משנה מסכת זבחים פרק י משנה א: כל התדיר מחבירו קודם את חבירו התמידים קודמין למוספין מוספי שבת קודמין למוספי ראש חדש מוספי ראש חדש קודמין למוספי ראש השנה שנאמר )במדבר כח( מלבד עולת הבקר אשר לעולת התמיד תעשו את אלה: 1.(The) Shelamim (type of Offerings) are Kodshim Kalim (they possess a lower level of sanctity than certain other Offerings). They may be slaughtered anywhere in the (Temple) Courtyard. Their blood is applied (to two opposing corners of the Altar) with two applications that are four (i.e. the application at each corner reaches two walls of the Altar). They (the parts given to the person bringing the Offering) may be eaten anywhere in the city (Jerusalem), by anyone (not just a Kohen), for two days and (the) night (in between. -

Humor in Talmud and Midrash

Tue 14, 21, 28 Apr 2015 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Jewish Community Center of Northern Virginia Adult Learning Institute Jewish Humor Through the Sages Contents Introduction Warning Humor in Tanach Humor in Talmud and Midrash Desire for accuracy Humor in the phrasing The A-Fortiori argument Stories of the rabbis Not for ladies The Jewish Sherlock Holmes Checks and balances Trying to fault the Torah Fervor Dreams Lying How many infractions? Conclusion Introduction -Not general presentation on Jewish humor: Just humor in Tanach, Talmud, Midrash, and other ancient Jewish sources. -Far from exhaustive. -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Talmud: Records teachings of more than 1,000 rabbis spanning 7 centuries (2nd BCE to 5th CE). Basis of all Jewish law. -Savoraim improved style in 6th-7th centuries CE. -Rabbis dream up hypothetical situations that are strange, farfetched, improbable, or even impossible. -To illustrate legal issues, entertain to make study less boring, and sharpen the mind with brainteasers. 1 -Going to extremes helps to understand difficult concepts. (E.g., Einstein's “thought experiments”.) -Some commentators say humor is not intentional: -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th century CE) always began his lectures with a joke: Before he began his lecture to the scholars, [Rabbah] used to say something funny, and the scholars were cheered. After that, he sat in awe and began the lecture. [Shabbat 30b] -Laughing and entertaining are important. Talmud: -Rabbi Beroka Hoza'ah often went to the marketplace at Be Lapat, where [the prophet] Elijah often appeared to him.