Through Students' Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Lb22 Lb172 Lb181 Lb203 Lb376 Lb384 Lb406 Lb425 Lb455 Lb476 Lb549 Lb661 Lr35]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2606/lb22-lb172-lb181-lb203-lb376-lb384-lb406-lb425-lb455-lb476-lb549-lb661-lr35-772606.webp)

[Lb22 Lb172 Lb181 Lb203 Lb376 Lb384 Lb406 Lb425 Lb455 Lb476 Lb549 Lb661 Lr35]

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Floor Debate February 09, 2017 [LB22 LB172 LB181 LB203 LB376 LB384 LB406 LB425 LB455 LB476 LB549 LB661 LR35] SPEAKER SCHEER PRESIDING SPEAKER SCHEER: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the George W. Norris Legislative Chamber for the twenty-sixth day of the One Hundred Fifth Legislature, First Session. Our chaplain today is Pastor Ed Milligan from the Douglas United Methodist Church in Douglas, Nebraska, Senator Watermeier's district. Would you please rise? PASTOR MILLIGAN: (Prayer offered.) SPEAKER SCHEER: Thank you, Pastor Milligan. I call to order the twenty-sixth day of the One Hundred Fifth Legislature, First Session. Senators, please record your presence. Roll call. Mr. Clerk, please record. ASSISTANT CLERK: There's a quorum present, Mr. President. SPEAKER SCHEER: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. Are there any corrections to the Journal? ASSISTANT CLERK: No corrections this morning. SPEAKER SCHEER: Thank you. Are there any messages, reports, or announcements? ASSISTANT CLERK: Mr. President, there are. Your Committee on Enrollment and Review reports LB22 as correctly engrossed and placed on Final Reading. Committee on Health and Human Services reports LB425 to General File with committee amendments. That's all I have this morning. (Legislative Journal page 451.) [LB22 LB425] SPEAKER SCHEER: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. Senator Harr has asked for a moment of personal privilege. Senator Harr, you're recognized. SENATOR HARR: Thank you, Mr. President and members of the body. Yesterday we had a Revenue hearing and I want to give you a little background and then I'm going to talk about it. -

PLANT in the SPOTLIGHT Cover of Ajuga in This Vignette at Pennsylvania's Chanticleer Garden

TheThe AmericanAmerican gardenergardener® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AmericanAmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety March / April 2013 Ornamental Grasses for small spaces Colorful, Flavorful Heirloom Tomatoes Powerhouse Plants with Multi-Seasonal Appeal Build an Easy Bamboo Fence contents Volume 92, Numbe1' 2 . March / Apl'il 2013 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS' FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS The AHS Encyclopediao/Gardening Techniques now available in paperback, the roth Great Gardens and Landscaping Symposium, registration opening soon for the National Children & Youth Garden Symposium, River Farm to participate in Garden Club of Virginia's Historic Garden Week II AHS NEWS SPECIAL Highlights from the AHS Travel Study Program trip to Spain. 12 AHS MEMBERS MAKING A DIFFERENCE Eva Monheim. 14 2013 GREAT AMERICAN GARDENERS AWARDS Meet this year's award recipients. 44 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Selecting disease-resistant plants. 18 FRAGRANT FLOWERING SHRUBS BY CAROLE OTTESEN Shrubs that bear fragrant flowers add an extra-sensory dimension 46 HOMEGROWN HARVEST to your landscape. Radish revelations. 48 TRAVELER'S GUIDE TO GARDENS 24 BUILD A BAMBOO FENCE BY RITA PELCZAR Windmill Island Gardens in Michigan. This easy-to-construct bamboo fence serves a variety of purposes and is attractive to boot. 50 BOOK REVIEWS No Nomeme VegetableGardening, The 28 GREAT GRASSES FOR SMALL SPACES BY KRIS WETHERBEE 2o-Minute Gardener, and World'sFair Gardem. Add texture and motion to your garden with these grasses and 52 GARDENER'S NOTEBOOK grasslike plants ideal for small sites and containers. Solomon's seal is Perennial Plant Association's 20I3 Plant of the Year, research shows plants 34 A SPECTRUM OF HEIRLOOM TOMATOES BY CRAIG LEHOULLIER may be able to communicate with each other, industry groups OFA and ANLAto If you enjoy growing heirloom tomatoes, you'll appreciate this consolidate, the Garden Club of America useful guide to some of the tastiest selections in a wide range of celebrates roo years, John Gaston Fairey colors. -

CITY of DEXTER ART SELECTION COMMITTEE MEETING 3/22/2017 @ 7:00 PM Location: Dexter District Library, 3255 Alpine St

CITY OF DEXTER ART SELECTION COMMITTEE MEETING 3/22/2017 @ 7:00 PM Location: Dexter District Library, 3255 Alpine St. A G E N D A 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ROLL CALL Victoria Schon Marni Schmid Martha Gregg Rich Bellas Toni Henkemeyer Ray Tell Donna Fisher – Ex Officio Phil Arbour Mary-Ellen Miller 3. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES – July 7, 2016 (Motion) 4. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (Motion) 5. CONSIDERATION OF: DEXTER ART GARDENS PROPOSAL EVALUATION A. Mary Angers B. Alfred Bruey C. Tim Burke D. Mark Chatterley E. Douglas Gruizenga F. Todd Kime G. Barry Parker H. Dane Porter I. Beth Scheffert 6. CITIZENS WISHING TO ADDRESS THE COMMITTEE 7. PROPOSED BUSINESS FOR FUTURE MEETINGS 8. ADJOURNMENT (Motion) CITY OF DEXTER ART SELECTION COMMITTEE REGULAR MEETING MEETING MINUTES July 7, 2016 The regular meeting of the City of Dexter Art Selection Committee was called to order at 7:00pm at the Dexter Senior Center, 7720 Ann Arbor St. ROLL CALL Committee Members Present: Victoria Schon, Marni Schmid, Rich Bellas, Phil Arbour, Mary- Ellen Miller, Donna Fisher (Ex-Officio) Committee Members Absent: Ray Tell, Toni Henkemeyer Others Present: Justin Breyer, Assistant to the City Manager; Mike Hand, Dexter Lions; Dennis Berry, Dexter Lions APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES Motion by Fisher, Seconded by Schon to approve the minutes from April 20, 2016. Unanimous Voice Vote Approval Motion Adopted APPROVAL OF AGENDA Motion by Fisher, Seconded by Arbour to appove the agenda as presented. Unanimous Voice Vote Approval Motion Adopted CITIZENS WISHING TO ADDRESS THE COMMISSION None NEW BUSINESS A. DISCUSSION OF: ART SELECTION CRITERIA The Committee discussed the Art Selection Criteria that the Arts, Culture, and Heritage Committee had voted to include in their Master Plan document. -

Arts Capital Art in the DC Metropolitan Area NEA ARTS

NEA ARTS number 2 2010 Arts Capital Art in the DC MetropolitAn AreA NEA ARTS 3 6 8 rebuilt through art a glimpse of the world vamos a la Calle! The Studio Theatre Gives a Building THEARC in Anacostia Celebrating DC’s Latino Arts and Culture Neighborhood New Life by Paulette Beete by Adam Kampe by Michael Gallant CoNNeCtivity betweeN Cultures: The World According to Dana Tai Soon Burgess .......................................................................10 by Victoria Hutter positive ChaNge: The Sitar Arts Center ..............................................................................................................................................12 by Pepper Smith a riCh aNd vibraNt Culture: The District of Columbia Jewish Community Center ........................................................................ 20 by Pepper Smith art out loud: Public Art Takes Over DC ............................................................................................................................................. 22 by Liz Stark NatioNal CouNCil oN the arts about this issue Rocco Landesman, Chairman James Ballinger Twenty years ago, boarded-up buildings in the Penn Quarter neighborhood were a Miguel Campaneria legacy from the 1968 riots, while the area around U Street, NW—once known as “Black Ben Donenberg Broadway” for its plethora of theaters—was a high-crime area, mostly devoid of busi- JoAnn Falletta Lee Greenwood nesses. Today, both neighborhoods are thriving, in no small part thanks to the arts Joan Israelite organizations that call those neighborhoods home. In the Penn Quarter neighborhood, Charlotte Kessler for example, the Shakespeare Theatre has paved the way for other businesses, like res- Bret Lott taurants and retail stores, to move to the area. It has further committed to the neighbor- Irvin Mayfield, Jr. Stephen Porter hood by building its new multimillion dollar Sidney Harman Hall just a few blocks down Barbara Ernst Prey from its Landsburgh Theater space. -

New Leaf Carbon Project

PROJECT DESCRIPTION VCS Version 3, CCB Standards Second Edition NEW LEAF CARBON PROJECT Document Prepared By Forests Alive on behalf of Tasmanian Land Conservancy Project Title New Leaf Carbon Project Version 4.0 Date of Issue 3rd June 2013 Prepared By Forests Alive Pty Ltd Contact Suite 7.03, 222 Pitt Street, Sydney, NSW, 2000, 61 282 709 908, [email protected], www.forestsalive.com v3.0 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION VCS Version 3, CCB Standards Second Edition Table of Contents 1 General ................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Summary Description of the Project (G3) ..................................................................................... 4 1.2 Project Location (G1 & G3) ........................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Conditions Prior to Project Initiation (G1) .................................................................................... 16 1.4 Project Proponent (G4) ............................................................................................................... 20 1.5 Other Entities Involved in the Project (G4) .................................................................................. 20 1.6 Project Start Date (G3) ................................................................................................................ 21 1.7 Project Crediting Period (G3) ..................................................................................................... -

A Year Ofgrowth

A Year of Growth 2013 Annual Report Sharing the wealth. Shaping the future. 1 From the Executive Director’s Desk Dear Friends, Here at Centre Foundation, we are truly “Building for the Future” and 2013 was a year that embodied that vision. We welcomed growth and transformation in our staff, our funds, our board, and our community! In December, I was honored to be named Executive Director upon the retirement of Al Jones. Earlier, we welcomed a new staff member, Irene Miller, in August. Jodi Pringle ended her very successful two- year term as board chair and has passed the gavel on to Amos Goodall. To see a complete list of our current staff – including Carrie Ryan, our new Deputy Director that joined us in March of 2014 – and Molly Kunkel board members, please see page 31. Executive Director Our assets grew 17.9% due to a dynamic combination of increased donations to existing funds, generous estate gifts through our Campbell Society, an increase in new funds established, and very strong investment returns. The full 2013 Financial Report and corresponding infographics can be found beginning on page 28. The Foundation’s ongoing support of community organizations kept growing, totaling over $10.7 million! A complete list of gifts to our funds starts on page 9, while a list of our lifetime grants to organizations begins on page 21. Sharing the wealth. Shaping the future. Centre Gives, our new granting program, completed its second year in May of 2013 and raised over half a million dollars for the participating organizations. More details can be found on page 12. -

Traditions of Strategic Thinking and the Sino-Indian War of 1962

A New Leaf for an Old Book: Traditions of Strategic Thinking and the Sino-Indian War of 1962 Arunabh Ghosh Senior History Thesis Principal Advisor: Prof. Paul Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment towards the History Major Department of History Haverford College 14th April 2003 1 I teach kings the history of their ancestors so that the lives of the ancients might serve them as an example, for the world is old, but the future springs from the past. —Djeli Mamoudou Kouyate, Griot, in Sundiata—An Epic of Old Mali “…But progressive research shows that every culture and every civilization has its own ‘miracle,’ and it is the purpose of historical investigation to reveal it. This cannot be achieved by seeking to discover identical values in every civilization, but rather by pointing out the significant values of each culture within its own context. This demands considerable honesty, as shortcomings have to be admitted in the same way as achievements are proclaimed.” —Romila Thapar in Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas Frontiers are indeed the razor's edge on which hang suspended the modern issues of war or peace, of life or death to nations. —Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy of India (1898-1905) and British Foreign Secretary 1919-24 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE i I. INTRODUCTION 01 II. STRATEGIC CULTURE—an appraisal and a framework 11 Definitions 13 Borders and Boundaries 14 Our Analytic Framework 15 III. ANALYTIC COMPARISONS ACROSS TIME 17 Geography 17 Political Systems and Structures 20 Structural Comparisons 27 Cultural Norms and Practices 30 IV. PROPOSITIONS—TRADITIONS OF STRATEGIC THINKING 35 India 35 China 38 V. -

JUPITER Ollino Homework • No Tests • No Stress

SPRING/SUMMERWINTER 20202020 JUPITER OLLINo Homework • No Tests • No Stress Harry Chernotsky, Ph.D. Jeffrey S. Morton, Ph.D. Lunafest® The Formation and Health & Wellness Film Festival Evolution of Galaxies Series (561) 799-8547 or (561) 799-8667 • www.fau.edu/osherjupiter 3 A Tribute to René Freidman, Founder Lifelong Learning Society at Florida Atlantic University, Jupiter 1997–2017 This past Thanksgiving, René Friedman, Founder and former Executive Director of Florida Atlantic University's Lifelong Learning Society in Jupiter, passed away. In 1997, René Friedman was given an opportunity to expand Florida Atlantic University’s Lifelong Learning Society (LLS) to the John D. MacArthur Campus in Jupiter, Florida. René knew that a non- profit lifelong learning program could thrive in Jupiter and would grow over years to support itself and be successful. Since its inception, the Lifelong Learning Society (LLS) has had several homes, starting at the NorthCorp building in Palm Beach Gardens. A preview showcase was presented in the spring of 1997 to 125 students. By the end of 1998, the new Lifelong Learning Society had grown to more than 426 members. As the program grew, classes were offered in a movie theater in Abacoa, churches, synagogues, and community centers. Finally in 1999, FAU opened the doors of the Jupiter campus and LLS was one of the founding academic units to first occupy space on the grounds. By the end of the year, the program had grown to 1,290. Shortly after the opening of the Jupiter Campus, René led staff and members in a building campaign that took four years. -

Annual Report 2012-2013

Annual Report 2012-2013 GettingGetting Involved.Involved. EndingEnding Hunger.Hunger. Message from the President & CEO and the Chairman of the Board of Directors It is with pride and a strong sense of accomplishment that the state last fiscal year and we distributed to more than 350 we present to you the St. Mary’s Food Bank 2012-2013 non-profit agency partners that are located in a service area Annual Report. that measures 81,000 square miles. The front cover and the pages that follow say it all and show it We are responsible for feeding hungry Arizonans in hundreds all: “Getting Involved. Ending Hunger.” This look back over last of communities from the Phoenix metro area, to Flagstaff, to fiscal year shows the food bank to be in strong fiscal shape, the Navajo Nation, to Lake Havasu City, to the Grand Canyon, well organized, efficient, and big. We are big because we have Verde Valley, Prescott, Snowflake, Gila Bend and Teec Nos Pos. to be – with such a large and varied distribution area, we see Every single month, St. Mary’s Food Bank distributes more than poverty and hunger everywhere it hides. And it is hiding in 40,000 emergency food boxes to households. We conduct more plain sight. than 40 fresh produce distributions in communities where fruits and vegetables are hard to come by – or are too expensive for More than 1.2 million Arizonans live at or below the poverty folks to afford. We provide 4,000 meals to kids after school each level, which means they are living very often with the reality and every weekday, trying to assure they don’t have to wait to that they don’t know where their next meal is coming from return back to school the next morning before they can eat again. -

Rashid Johnson

RASHID JOHNSON born 1977, Chicago IL lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 2004 MFA, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2000 BA, Columbia College, Chicago, IL SELECTED SOLO / TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2021 Black and Blue, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA The Crisis, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, NY Summer Projects: Rashid Johnson, Creative Time, New York, NY The Bruising: For Jules, The Bird, Jack and Leni, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR Capsule, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada 2020 Waves, Hauser & Wirth, London, England Stage, PS1 COURTYARD: an experiment in creative ecologies, MoMA PS1, Long Island City, NY 2019 The Hikers, Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, Mexico The Hikers, Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, CO It Never Entered My Mind, Hauser & Wirth, St. Moritz, Switzerland Anxious Audience, Fleck Clerestory Commissioning Project, curated by Lauren Barnes, The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada The Hikers, Hauser & Wirth, New York, NY 2018 *No More Water, Lismore Castle Arts, Lismore, Ireland *The Rainbow Sign, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Provocations: Rashid Johnson, Institute for Contemporary Art, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 2017 Anxious Audience, organized by Annin Arts, Billboard 8171, London Bridge, England [email protected] www.davidkordanskygallery.com T: 323.935.3030 F: 323.935.3031 Stranger, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Bruton, England Rashid Johnson: The New Black Yoga and Samuel in Space, McNay Art Museum, -

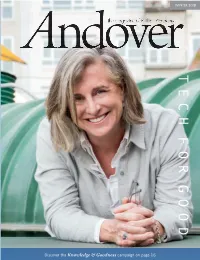

T E C H F O R G O

WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER 2 018 -

2011/12 Annual Report

2011/12 ANNUAL REPORT Arts Council of Princeton TABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Report for the 1 Greetings from the Board President Fiscal Year 2011/12 2 Greetings from the Executive Director 7/1/11 – 6/30/12 3 The Numbers Tell the Story 4 Arts Education 5 Free Community Outreach 6 Communiversity Festival of the Arts 7 Community Cultural Events 8 Exhibitions and Anne Reeves Artists-in-Residence 9 Performances 10 Fundraising Events 11 Circle of Friends 12 Annual Meeting and Our Volunteers 14 Finances 15 Our Supporters (Thank you!) 28 Community Partners 29 Pinot to Picasso Artists 30 ACP Faculty/Teaching Artists 31 Board of Trustees, Staff and Consultants, Photo credits COVER: Continuum, 2012, concept drawing by Illia Barger, 2012 Anne Reeves Artist-in-Residence, for public mural on the Terra Momo Bread Company wall, corner of Witherspoon and Paul Robeson Place. Illia is an acclaimed painter of large scale works and murals and owner/designer of Pantaluna, a line of creative, upcycled clothing. THE PROJECT Continuum commemorates three collaborative temporary public art installations located in empty lots on Paul Robeson Place from 2002-2009. Herban Garden, Terra Momo’s produce garden, was created by landscape designer Peter Soderman. It became the inspiration for two subsequent public sculpture gardens: Writer’s Block and Quark Park, conceptualized by Kevin Wilkes, AIA, Peter Soderman and Alan Goodheart, ASLA. We wish to thank Terra Momo Bread Company and the Residences at Palmer Square for partnering with us on this important public art project. We’d also like to thank the following lead sponsors: Timothy M.