THE CENTRAL LINE EXTENSIONS and THEIR IMPLEMENTATIONS by Eric Stuart BACKGROUND Until the Industrial Revolution, Cities Tended to Be Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A31 Note: Gunnersbury Station Does Not Have OWER H91 E D

C R S D E A U T S A VE N E R A N B B D L W Based on Bartholomews mapping. Reproduced by permission of S R E i N U st A R O HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., Bishopbriggs, Glasgow. 2013Y ri E E A Y c W R A t D A AD www.bartholomewmaps.com N C R 272 O Y V L D R i TO T AM 272 OL E H D BB N n A O CAN CO By Train e N Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative N U L E n w i a L Getting to BSI m lk 5 i AVE 1 ng N A Acton0- t V 1 im • The London Overground runs between E t e e LD ROAD B491 D N a SOUTHFIE E Y Town fr R Address: Chiswick Tower, U imR B o B E U O 440 m Richmond and Stratford stopping at Travel to E x L D B A R o S L AD R r O E RO O s 389 Chiswick High Road, London, W4 4AL Y R G R E p EY L i SPELDHUR Gunnersbury. ID ST R A R R t RO M p NR B E A O N e D NU O H L A A UB E LL C D GS BO T Y British Standards 1 R E RSET E E 9 N L SOM T N All visitors must enter the building through F 44 U N H • The ‘Hounslow Loop’ has stations at G SOUTH ROAD BEDFORD B E3 E B E R the main entrance on Chiswick High Road O Kew Bridge, Richmond, Weybridge, N O L PARK D Institution S ACTON L A A A D N E O R E O D and report to Reception on arrival. -

Planning Committee 23/05/2018 Schedule Item No. 03

Planning Committee 23/05/2018 Schedule Item No. 03 Ref : 181062OPDFUL Address: 140 Wales Farm Road, Acton W3 6UG Ward: East Acton Proposal: Demolition of existing buildings and redevelopment of site to provide 3 No. residential buildings between 12 and 25 storeys in height to provide 380 residential units (comprising 66 No. studios, 190 No. 1 bed, 104 No. 2 bed and 20 No. 3 bed flats) and 1,403 sq.m of flexible A1/A2/A3/A4/A5/B1/D1/D2 floor space; the provision of public open space, roof top amenity space, landscaping, car and cycle parking, and refuse storage (Full Planning Application accompanied by an Environmental Impact Assessment: Resubmission). Drawing numbers/plans: Drawing numbers for Job Number 16043: (01)-E-100 Revision PL; (01)-E-001 Revision PL; (01)-E-002 Revision PL; (01)-E- 003 Revision PL; (01)-E-004 Revision PL; (03)-P-S000 Revision PL; (01)-P-S001 Revision PL; (01)-P-S002 Revision PL; (03)-E-200 Revision PL; (03)-E-201 Revision A; (03)-E-202 Revision PL; (03)-E-203 Revision PL; (03)-E-204 Revision PL; (03)-E-205 Revision PL; (03)-E-206 Revision PL; (03)-E-207 Revision PL; (03)-E-220 Revision A; (03)-E-221 Revision PL; (03)-P-0B0 Revision PL; (03)-P-0G0 Revision PL; (03)-P-0M0 Revision PL; (03)-P-001 Revision A; (03)-P-002 Revision A; (03)-P-011 Revision A; (03)-P-012 Revision A; (03)-P-013 Revision PL; (03)-P-015 Revision PL; (03)-P-016 Revision PL; (03)-P-022 Revision PL; (03)-P-023 Revision PL; (03)-P-0R0 Revision PL; (03)-X-100 Revision PL; (03)-X-101 Revision PL; (03)-X-102 Revision PL; (03)-X-103 Revision PL; (03)-E-250 -

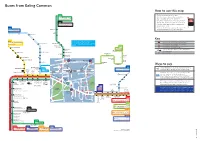

Buses from Ealing Common

Buses from Ealing Common 483 towards Harrow Bus Station for Harrow-on-the-Hill Buses from Ealing Commonfrom stops EM, EP, ER N83 towards Golders Green from stops EM, EP, ER N7 483 towards Northolt Alperton towards Harrow Bus Station for Harrow-on-the-Hill from stops EH, EJ, EK, EL from stops EM, EP, ER 483 N83 N7 Argyle Road N83 towards Golders Green from stops EM, EP, ER N7 towardsE11 Northolt Alperton Route 112 towards North Finchley does not call at any bus stops within the central map. fromtowards stops Greenford EH, EJ, EK Broadway, EL Pitshanger Lane Ealing Road Route 112 towards North Finchley can be boarded from stops EW 483 at stops on Hanger Lane (Hillcrest Road, Station or N83 N7 Argyle Road Hanger Lane Gyratory). Quill Street 218 Castle Bar Park from stops Hanger Lane EA, ED, EE, EF Gyratory North Acton Woodeld Road Hanger Lane E11 Copley Close Route 112 towards North Finchley does not call 483 N83 at any bus stops within the central map. Northelds towards Greenford Broadway Road Pitshanger Lane Ealing Road Hanger Lane Route 112 towards North Finchley can be boarded Victoria from stops EW at stops on Hanger Lane (Hillcrest Road, Station or E11 Hillcrest Road 218 Road Browning Avenue N7 Hanger Lane Gyratory). 218 Quill Street Eastelds 218 Castle Bar Park Drayton Green Road North Ealing West Acton from stops Gypsy Hangerq Lane EA, ED, EE, EF Corner Eaton Rise IVE STATION APPROA GyratoryEEN’S DR CH e Westelds QU Road North Acton Woodeld Road ROAD Hanger Lane AD Copley Close 112 ELEY RO Noel Road MAD Northelds 483 N83‰ L Road -

Ealing Council Sites Included

Appendix 1 Water, Wastewater and Ancillary Services procurement - Ealing Council sites included Site name Site address Postcode Smith's Farm Community Centre 61 Hotspur Road, Northolt UB5 6TN Northolt Park Play Centre Newmarket Avenue, Northolt UB5 4HB Westside Young People's Centre Churchfield Road, Ealing W13 9NF Woodlands Park Pond Woodlands Avenue, London W3 9BU High Lane Allotments High Lane, London W7 3RT Queen Annes Gardens Allotments Queen Annes Gardens, London W5 5QD Blondin Allotments 267-269 Boston Manor Road, Brentford TW8 9LF Carmelita House 21-22 The Mall, London W5 2PJ Ealing Alternative Provision Compton Close, Ealing W13 0LR Sunlight Community Centre London W3 8RF Short Break Services 62 Green Lane, Hanwell W7 2PB South Ealing Cemetery South Ealing Road, Ealing W5 4RH Pitzhanger Manor House & Gallery Walpole Park, Ma:oc -ane, -ondon W5 5EQ North Acton Playing Fields Noel Road, Acton W3 0JD Hanwell Zoo (Brent Lodge Park) Church Road, London W7 3BP Horizons Centre 15 Cherington Road, Hanwell W7 3HL Hanwell Children's Centre 25a -aurel 0ardens, Hanwell W7 3JG Perceval House 14-16 Uxbridge Road, Ealing W5 2HL 2 Cheltenham Place London W3 8JS Framfield Road Allotments Framfield Road, London W7 1NG Ealing Town Hall New Broadway, Ealing, London W5 2BY Popes Lane Allotments Popes Lane, Ealing W5 4NT Southall Recreation Ground Stratford Road, Southall UB2 5PQ Public Convenience, Maytrees Rest Gardens South Ealing Road, Ealing W5 4QT Horn Lane Allotments Horn Lane, London W3 0BP Tennis Courts Lammas Park, London, W5 5JH Michael -

Mayfair Area Guide

Mayfair Area Guide Living in Mayfair • Mayfair encompasses the area situated between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane, in the very heart of London’s West End, and adjacent to St James’s and its glorious Royal parks to the south. Overview • For over 300 years, Mayfair and St James’s have provided grand homes, luxury goods and services to the aristocracy. The area is characterised by its splendid period architecture, beautiful shop fronts, leading art galleries, auction houses, wine merchants, cosmopolitan restaurants, 5 star hotels and gentleman’s clubs. Did You Know • Mayfair is named after an annual 15 day long May Fair that took place on the site that is now Shepherd Market, from 1686 until 1764. • There is a disused tube station on Down Street that used to serve the Piccadilly line. It was closed in 1932 and was later used by Winston Churchill as an underground bunker during the Second World War. • No. 50 Berkeley Square is said to be the most haunted house in London, so much so that it will give any psychic an electric shock if they touch the external brickwork. • Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was born in a house on Bruton Street and lived in Mayfair during her infancy. Her future husband Prince Philip had his stag night at The Dorchester. • The oldest outdoor statue in London is located above the entrance of Sotheby’s on New Bond Street. The Ancient Egyptian effigy of the lion-goddess Sekmet is carved from black igneous rock and dates to around 1320 BC. -

Report to Overview & Scrutiny Committee Date of Meeting: 16 July

Report to Overview & Scrutiny Committee Date of meeting: 16 July 2013 Portfolio: Safer Greener and Transport Subject: Crossrail 2 Consultation Officer contact for further information: John Preston (01992 564111) Committee Secretary: Simon Hill (01992 564249) Recommendations/Decisions Required: 1. That the Committee consider the issues set out in this report, and determine what view to give to the consultation in respect of each issue having regard to the consideration given to these issues at the Planning Services Standing Scrutiny Panel and as set out in paragraph two of this report. 2. That the views of EFDC are made known to other relevant stakeholders, including; • London Borough of Redbridge • London Borough of Waltham Forest • West Anglia Routes Group • North London Strategic Alliance • London Stansted Cambridge Consortium • Essex County Council • Borough of Broxbourne • Corporation of London • LVRPA • SELEP • London First • Members of Parliament for the Epping, Harlow and Brentwood & Ongar constituencies. Report: 1. This report was first considered at the Planning Services Scrutiny Panel meeting on 18 June 2013. The Portfolio Holders for Planning and for Asset Management and Economic Development have assisted in consideration of the issues and concur with the recommendations in this report. 2. The panel reached the following conclusions; • Epping has become an acceptable terminus for the Central Line, but even though there may be economic advantages there would be economic and practical disadvantages in it being a terminus for Crossrail 2. • That a generally positive response should be given to the consultation. • That the Regional rather than the Metro option was preferred, in particular if accessible to residents and businesses within the District. -

UK Jubilee Line Extension (JLE)

UK Jubilee Line Extension (JLE) - 1 - This report was compiled by the OMEGA Centre, University College London. Please Note: This Project Profile has been prepared as part of the ongoing OMEGA Centre of Excellence work on Mega Urban Transport Projects. The information presented in the Profile is essentially a 'work in progress' and will be updated/amended as necessary as work proceeds. Readers are therefore advised to periodically check for any updates or revisions. The Centre and its collaborators/partners have obtained data from sources believed to be reliable and have made every reasonable effort to ensure its accuracy. However, the Centre and its collaborators/partners cannot assume responsibility for errors and omissions in the data nor in the documentation accompanying them. - 2 - CONTENTS A INTRODUCTION Type of Project Location Major Associated Developments Current Status B BACKGROUND TO PROJECT Principal Project Objectives Key Enabling Mechanisms and Timeline of Key Decisions Principal Organisations Involved • Central Government Bodies/Departments • Local Government • London Underground Limited • Olympia & York • The coordinating group • Contractors Planning and Environmental Regime • The JLE Planning Regime • The Environmental Statement • Project Environmental Policy & the Environmental Management System (EMS) • Archaeological Impact Assessment • Public Consultation • Ecological Mitigation • Regeneration Land Acquisition C PRINCIPAL PROJECT CHARACTERISTICS Route Description Main Termini and Intermediate Stations • Westminster -

Planning Committee 09/11/2011 Schedule Item 04

Planning Committee 09/11/2011 Schedule Item 04 Ref: P/2011/2338 Ward: East Acton Address: Portal Way, North Acton, W3 6UU Proposal: Redevelopment to provide two mixed-use buildings with roof level amenity space (seven-storeys and eight-storeys) to provide 184 student units on upper floors and 382m2 on ground floor for use as student lounge and lobby, and uses within Retail (Use Class A1), Financial and Professional (Use Class A2), Restaurants and Cafes (Use Class A3), Business (Use Class B1) or Non-residential Institutions (Use Class D1); creation of biodiversity park and community pocket park; provision of four parking spaces and 132 cycle parking spaces Drawing Nos: JKK6263 1 REVC and JKK6263 2 REVC. 5303/P/5.00A, 5303/P/5.01A, 5303/P/5.02B, 5303/P/5.03B, 5303/P/5.04B, 5303/P/5.05B, 5303/P/5.06, 5303/P/5.07, 5303/P/5.08, 5303/P/5.09, 5303/P/5.010, 5303/P/5.013, 5303/P/5.014, 5303/P/5.015, 5303/P/5.016, 5303/P/5.017, 5303/P/5.018 and 5303/P/5.019. 1302/01 REVC, 1302/02 REVB, 1302/03 REVB and 1302/04 REVA. Accompanying documents Planning Statement (prepared by CGMS) Air Quality Assessment (prepared by RPS) BREEAM Assessment (prepared by Eight Associates) Building for Life Assessment (prepared by AR Urbanism) Ecology Report (prepared by Thomson Ecology) Energy and Sustainability Assessment (prepared by Flatt Consulting) Flood Risk Assessment (prepared by RPS) Fire Safety Review (prepared by International Fire Safety Consultants Ltd) Landscape Scheme (prepared by Liz Lake) Noise Assessments (prepared by MoirHands) Site Investigation Report -

Crossrail 2 Summary of Option Development

Crossrail 2: Summary of Option Development May 2013 AECOM for TfL Crossrail 2: Summary of Option Development 2 Introduction Transport for London (TfL) working with Network Rail are undertaking a public consultation on proposals for a new rail line to cross London, known as Crossrail 2. This new line, previously known as the Chelsea-Hackney line, would run on a south west to north east alignment. The response to the public consultation will help shape future work on the development of Crossrail 2. The purpose of this document is to provide stakeholders and the general public with information on the need for and background to the proposed new line and the development of possible future options. Background to Crossrail 2 The concept of cross-London tunnelled rail services connecting mainline services first emerged in the 1944 Greater London Plan1 with a focus on east-west services. It was six decades later, however, before a hybrid bill for an east-west Crossrail was placed before Parliament in 2005. Crossrail gained Royal Assent in 2008, construction commenced in 2009 and trains are due to begin operating in 2018. In 1991 the route of the Chelsea-Hackney line (Figure 1), envisaged at that time as an Underground line, was safeguarded by directions issued by the Secretary of State for transport to protect the route from development. However, with the emphasis on east-west Crossrail, the Chelsea-Hackney route was not progressed until more recently. In 2008 the safeguarding for the Chelsea-Hackney line was refreshed. In 2009 the Department for Transport asked the Mayor of London to review the case with a view to re-examining the thinking behind the scheme, identifying new options and reviewing the safeguarding of the existing route. -

A Brief History of London Transport V1

London Transport A brief history London Transport A brief history Sim Harris First published 2011 by Railhub Publications Dunstable, Bedfordshire www.railhub2.co.uk © Sim Harris 2011 The moral right of Sim Harris to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, circulated or exploited in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the copyright holder, with the exception of excerpts published for the purposes of review or brief quotations, in connection with which this work shall be cited unambiguously as the true source. ISBN awaited This digital edition designed and created by the Railhub studio Contents 1 ‘Sensational plan’ 11 2 ‘Serious doubts’ 23 3 ‘Fares fair’ 31 Chronology 40 Notes on sources 41 8 9 LONDON TRANSPORT Daily Express 3 December 1929, reporting the announcement of a new Passenger Board for London, and the new LPTB logo, which was soon replaced by the classic ‘bullseye’ 10 Chapter One ‘Sensational plan’ T caused by unrestricted competition by bus operators on the streets of London had become extreme by the early 1920s, when ‘pirate’ buses concentrated on peak hour flows, causing traffic disruption and neglecting passengers at quieter times. Their presence led to calls for controls, which were largely achieved by the London Traffic Act in 1924. This allowed the authorities to ‘designate’ streets and so restrict the routes available to the pirates. But further reforms were urged, particularly by Labour politi- cians, and in December 1929 the Minister of Transport Herbert Morrison published the Labour government’s proposed London Pas- senger Transport Bill. -

London Transport Records at the Public Record Office

CONTENTS Introduction Page 4 Abbreviations used in this book Page 3 Accidents on the London Underground Page 4 Staff Records Pages 6-7 PART A - List of former ‘British Transport Historical Records’ related to London Transport, which have been transferred to the Greater London Record Office - continued from Part One (additional notes regarding this location) Page 8 PART C - List of former ‘British Transport Historical Records’ related to London Transport, which are still at the Public Record Office - continued from Part One Pages 9-12 PART D - Other records related to London Transport including Government Departments - continued from Part One Pages 13-66 PART E - List of former ‘Department of Education and Science’ records transferred from the PRO to the Victoria & Albert Museum Pages 67 APPENDIX 1 - PRO Class AN2 Pages to follow APPENDIX 2 - PRO Class MT29 Page 51- (on disc) APPENDIX 3 - Other places which have LT related records Pages 68-71 PRO document class headings: AH (Location of Offices Bureau) Page 13 AN (Railway Executive Committee/BTC/British Railways Board) - continued from Part One Pages 14-26 AN2 (Railway Executive Committee, War of 1939. Records cover period from 1939-1947) Pages to follow AT (Department of the Environment and Predecessors) Page 27 AVIA (Ministry of Aviation/Ministry of Aircraft Production) Page 27 AY (Records of various research institutes) Page 27 BL (Council on Tribunals) Page 27 BT (Board of Trade) - continued from Part One Page 28-34 CAB (Cabinet Papers) Page 35-36 CK (Commission for Racial Equality/Race -

Priority Order List Mayor's Question Time Wednesday 18 December 2013

Agenda Item 5 PriorityOrderList Mayor'sQuestionTime Wednesday18December2013 ReportNo:5 Subject: QuestionstotheMayor Reportof: ExecutiveDirectorofSecretariat QuestionsnotaskedduringMayor’sQuestionTimewillbegivenawritten responsebyMonday23December2013. "Fitforthefuture"programme QuestionNo:2013/4865 ValerieShawcross Isthe"fitforthefuture"programmeofstaffingcutstostationsaffectedbythisyear'sfare decision? Olympic TransportLegacy QuestionNo:2013/4711 RichardTracey WhatprogresshasbeenmadeinmakingtheJavelintrainservice,whichwassosuccessful duringtheOlympics,availabletoLondonersusingtravelcardsandOystercards,as recommendedbytherecentHouseofLordsSelectCommitteereport? Tackling excesswinterdeathsandfuelpoverty QuestionNo:2013/4637 JennyJones WhatimpactwilltheGovernment'sdecisiontoscalebacktheEnergyCompanyObligation haveonyourplanstotackleLondon'senergyinefficientandhardtotreathomes? Making CyclingSaferinLondon QuestionNo:2013/5263 CarolinePidgeon WhatactionareyounowtakingtomakecyclingsaferinLondon? Page 1 Juniorneighbourhoodwardens' scheme QuestionNo:2013/4709 RogerEvans SouthamptonCouncilhasajuniorneighbourhoodwardensscheme,wherebyyoungpeople agedseventotwelvehelplookafterthehousingestatesonwhichtheylive.Wouldyou considerpilotingasimilarschemetoencourageyoungpeopletoshareintheresponsibility fortheirneighbourhoods,throughactivitiessuchaslitter-picking,gardeningandpainting? Risingfuelbills QuestionNo:2013/4866 MuradQureshi WhatwouldLondonersbenefitfrommost,cutstogreenleviesthatfundthewaronfuel povertyora20-monthenergypricefreeze?