On the Road, with 80 Lucky Dogs Interview by Jim Kennedy ’75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talk to the Paw

Talk to the Paw Support Dogs, Inc. Volunteer Newsletter Spring 2015 Support Dogs, Inc Volunteer Newsletter TOUCH Program - Reformatted In 2013, the VAC began looking at the TOUCH program. We know the program is wonderful but we wanted to see if there were any changes or improvements that would make it even better. After careful consideration, in 2014, we implemented a segmented class format, along with an instructor intern program. The segmented class format allows volunteers to get out in the community sooner and also allows the handler to participate in only the segments desired. TOUCH still begins with a temperament evaluation, after successful completion of an adult obedience class. Next, instead of the 12-week class, there are segmented classes. First, the team starts with a four-week TOUCH Prep Class. After successful completion of this class, the team can move to the Adult class and/or the Paws for Reading class. The Paws class requires a recommendation from the instructor and is a two hour class. The Adult class is a five-week class. After successful completion of the Adult segment, the team can begin visiting in adult facilities. If desired and if instructor recommended, the team may enroll in the Children’s class. Upon successful completion of the four-week Children’s class, the team can visit in non-acute child facilities. This does not include Children’s Hospital, Shriner’s Hospital or Ranken Jordan. In order to visit these facilities, the Acute class is required. The Acute segment is a two- week class. Before a handler can take the Acute class, the team must have made 12 visits in six months or twelve months at a non-acute child facility. -

Parties Interested in Contracting to Part D Applicants

Parties Interested in Contracting with Part D Applicants Consultants/Implementation Contractors Advanced Pharmacy Consulting Services Address: 7201 W 35th Street, Sioux Falls, SD 57106 Contact Person: Steve Bultje PharmD Phone Number: 605-212-4114 E-mail address: [email protected] Services: Medication Therapy Management Services Advance Business Graphics Address: 3810 Wabash Drive, Mira Loma, CA 91752 Contact Person: Dan Ablett, Executive Vice President, Sales & Marketing, Craig Clark, Marketing Director Phone Number: 951-361-7100; 951-361-7126 E-mail address: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.abgraphics.com Services: Call Center Aegon Direct Marketing Services, Inc. Address: 520 Park Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21201 Contact Person: Jeff Ray Phone Number: (410) 209-5346 E-mail address: [email protected] Services: Marketing Firm Alliance HealthCard, Inc. Address: 3500 Parkway Lane, Suite 720, Norcross, GA 30092 Contact Person: James Mahony Phone Number: 770-734-9255 ext. 216 E-mail address: [email protected] Website: www.alliancehealthcard.com Services: Call Center & Marketing Firm Allison Helleson, R. Ph.CGP Address: 5985 Kensington Drive, Plano Texas 75093 Contact Person: Alison Helleson Phone Number: 214-213-5345 E-mail address: [email protected] Services: Medication Therapy Management Services American Health Care Administrative Services, Inc Address: 3001 Douglas Blvd. Ste. 320 Contact Person: Grover Lee, Pharm D., BCMCM Phone Number: 916-773-7227 E-mail Address: [email protected] -

Judy: a Dog in a Million Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JUDY: A DOG IN A MILLION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Damien Lewis | 10 pages | 01 Jan 2015 | W F Howes Ltd | 9781471284243 | English | Rearsby, United Kingdom Judy: A Dog in a Million PDF Book Youth Field Trial Alliance. Judy fell pregnant, and gave birth to thirteen puppies. When he boarded the ship, Judy climbed into a sack and Williams slung it over his shoulder to take on board. We empower all our people, by respecting and valuing what makes them different. Judy, the heroine dog in a million. The guards had grown tired of the dog and sentenced her to death. Schools PDSA. Judy had won hers for her many life-saving acts aboard the Royal Navy gunboats and in the POW camps, and for the role she played everywhere by boosting morale. If you only read one book in your life read this book. Year published He realised as he looked back that she had been pulling him away from a Leopard. Sign In. Goldstone-Books via United Kingdom. Judy with her handler Frank Williams. Author Damien Lewis. Archived from the original on 9 November The Books Podcast. She kept man and mind together in the darkest days, with her love and her loyalty. Afterwards they contacted the Panay and offered them the bell back in return for Judy. Role Finder Start your Royal Navy journey by finding your perfect role. Joining Everything you need to know about joining the Royal Navy, in one place. In stock. He has written a dozen non-fiction and fiction books, topping bestseller lists worldwide, and is published in some thirty languages. -

Dogs for the Deaf, Inc. Assistance Dogs International

Canine Listener Robin Dickson, Pres./CEO Fed. Tax ID #93-0681311 Fall 2011 • NO. 118 The American Humane Association (AHA) held a very special event this year - the HERO DOG AWARDS INAUGURAL EVENT. AHA started the event by establishing eight categories of Hero Dogs. Those categories were: Law Enforcement/Arson Dog Service Dog Therapy Dog Military Dog Guide Dog Hearing Dog Search and Rescue Dog Emerging Hero Dog Dogs were nominated within each category and their stories were sent to AHA who posted the dogs’ pictures and stories on the internet so people could vote for their favorite Hero Dog. The partners of each dog chose a charity to receive a $5,000 prize if their dog won their category. Then, the winners of each category would go to Beverly Hills, California, for a red carpet gala awards ceremony where the overall Hero Dog Award winner would be chosen by a group of celeb- rity judges, and that overall winning team would receive an additional $10,000 for their charity. We were thrilled when one of our Hearing Dogs, Harley, won the Hearing Dog category, earning a trip to the awards ceremony and $5,000 for DFD. Although Harley did not win the overall award, we are so proud of him and Nancy & Harley his partner Nancy for representing all of our wonderfully trained Hearing Dog teams. Nancy wrote the following, telling of their experi- ences at this special red carpet event: “What a weekend of sights, sounds, feelings, re- alizations, disappointments, joys, triumphs, and inspirations! It was great fun, exhausting, exhila- rating, and so interesting. -

Dogs in History

dorothystewart.net Newfoundland Mi'kmaq, family history, Coronation Street, etc. Dogshttp://dorothystewart.net in War Date : September 10, 2014 - by Jim Stewart, originally published on the STDOA website Sergeant Gander The WWII story of Sergeant Gander is one of courage, companionship, and sacrifice. Gander was posthumously awarded the Dickin Medal in 2000. Sgt. Gander, a Newfoundland dog, and other animals who served in Canada's military are recognized on the Veterans Affairs Canada. A grenade killed Sgt. Gander. He grabbed it and ran, taking it away from his men. It took his life when it exploded, but his action saved many. The book Sergeant Gander: A Canadian Hero, by St. Thomas' own Robyn Walker, is called "a fascinating account of the Royal Rifles of Canada's canine mascot, and his devotion to duty during the Battle of Hong Kong in the Second World War." Intended for children, it is very informative for anyone interested in Newfoundland dogs, Newfoundland or Canada's role in WWII. The Amazon link is here. 1 / 21 dorothystewart.net Newfoundland Mi'kmaq, family history, Coronation Street, etc. Dickenhttp://dorothystewart.net Medal The Dickin Medal, at left, has been awarded to heroic animals by the UK's People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) since 1914. It has an amazing history and the list of recipients includes dogs, pigeons, cats, and horses. A WWII British recipient of the award was Judy, shown at right wearing her Dickin Medal, the only dog to ever officially be listed as a Prisoner of War in a Japanese prison camp. 2 / 21 dorothystewart.net Newfoundland Mi'kmaq, family history, Coronation Street, etc. -

People, Paws & Partnerships

20 IMPACT REPORT People, Paws & 20 Partnerships ABOUT HELPING PAWS OUR MISSION The mission of Helping Paws is to further people’s independence and quality of life through the use of Assistance Dogs. The human/animal bond is the foundation of Helping Paws. We celebrate the mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals, honoring the dignity and well-being of all. ASSISTANCE DOGS INTERNATIONAL MEMBER Helping Paws is an accredited member of Assistance Dogs International (ADI). We adhere to their requirements in training our service dogs. ADI works to improve the areas of training, placement and utilization of assistance dogs as well as staff and volunteer education. For more information on ADI, visit their website at www.assistancedogsinternational.org. BOARD OF MANAGEMENT AND INSTRUCTORS DIRECTORS DIRECTORS OFFICERS Pam Anderson, Director of Development Ryan Evers – President Eileen Bohn, Director of Programs Kathleen Statler – Vice President STAFF James Ryan – Treasurer Chelsey Bosak, Programs Department Administrative Coordinator Andrea Shealy – Secretary Judy Campbell, Foster Home Coordinator and Instructor MEMBERS Laura Gentry, Canine Care Coordinator and Instructor Ashley Groshek Brenda Hawley, Volunteer and Social Media Coordinator Judy Hovanes Sue Kliewer, Client Services Coordinator and Instructor Mike Hogan Jonathan Kramer, Communications and Special Projects Coordinator Alison Lienau Judy Michurski, Veteran Program Coordinator and Breeding Reid Mason Program Coordinator Kathleen Statler Jill Rovner, Development -

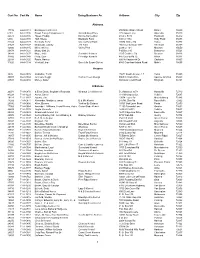

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

All Small-Sized Cwss That Have Certified Completion of Their RRA (Pdf)

Community water systems serving a population of 3,001 to 49,999 that certified completion of a risk and resilience assessment as required by Section 2013 of America's Water Infrastructure Act, as of July 30, 2021. PWSID Community Water System Town/City State ZIP Code 1 001570671 PACE WATER SYSTEM, INC. PACE FL 32571-0750 2 010106001 MPTN Water Treatment Department Mashantucket CT 06338 3 010109005 Mohegan Tribal Utility Authority Uncasville CT 06382 4 020000005 ST. REGIS MOHAWK TRIBE Akwesasne NY 13655 5 043740039 CHEROKEE WATER SYSTEM CHEROKEE NC 28719 6 055293201 MT. PLEASANT Mount Pleasant MI 48858 7 055293603 East Bay Water Works Peshawbestown MI 49682 8 055293611 HANNAHVILLE COMMUNITY WILSON MI 49896-9728 9 055293702 LITTLE RIVER TRIBAL WATER SYSTEM Manistee MI 49660 10 055294502 Prairie Island Indian Community Welch MN 55089 11 055294503 Lower Sioux Indian Community Morton MN 56270 12 055294506 South Water Treatment Plant Prior Lake MN 55372 13 055295003 SOUTH-CENTRAL WATER SYSTEM Bowler WI 54416 14 055295310 Giiwedin Hayward WI 54843 15 055295401 Lac du Flambeau Lac du Flambeau WI 54538 16 055295508 KESHENA KESHENA WI 54135 17 055295703 ONEIDA #1 OR SITE #1 ONEIDA WI 54155 18 061020808 POTTAWATOMIE CO. RWD #3 (DALE PLANT) Shawnee OK 74804 19 061620001 Reservation Water System Eagle Pass TX 78852 20 062004336 Chicksaw Winstar Water System Ada OK 74821 21 063501100 POJOAQUE SOUTH Santa Fe NM 87506 22 063501109 Isleta Eastside Isleta NM 87022 23 063501124 Pueblo of Zuni - Zuni Utility Department Zuni NM 87327 24 063503109 Isleta Shea Whiff Isleta NM 87022 25 063503111 LAGUNA VALLEY LAGUNA, NM 87026 NM 87007 26 063506008 Mescalero Apache Inn of the Mountain Gods Public Water System Mescalero NM 88340 27 070000003 SAC & FOX (MESKWAKI) IN IOWA TAMA IA 52339 28 083090091 TOWN OF BROWNING BROWNING MT 59417 29 083890023 Turtle Mountain Public Utilities Commission Belcourt ND 58316 30 083890025 Spirit Lake Water Management RWS St. -

![Pets + the People Who Love Them | Spring 2016 [FROM the CEO] an Amazing Journey](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5776/pets-the-people-who-love-them-spring-2016-from-the-ceo-an-amazing-journey-3085776.webp)

Pets + the People Who Love Them | Spring 2016 [FROM the CEO] an Amazing Journey

TAIL’STALES Pets + The people who love them | Spring 2016 [FROM THE CEO] An amazing journey... This is my last note in the newsletter. I will help every single soul who finds their way to be retiring soon. The date will be determined our doors. by the arrival of my replacement. And the volunteers are with us at every I have been in the animal welfare world turn. They are here every single day of the for more than a quarter of a century, with year, regardless of the weather, the time or the last 18 at the Nebraska the day. They make sure every possible dog Humane Society. It has is walked, petted and loved. They provide been an amazing journey. I foster care for those in need of healing have witnessed wonderful prior to adoption. They help care for all the people with hearts the size animals at the shelter, as well as help adopt of the state; people who will them into loving homes. Our volunteers do anything and everything touch every aspect of the shelter. possible to help animals Last, but surely not least, is Friends and who feel that our companion animals Forever. This wonderful, generous and deserve to live in an environment free of compassionate group was formed before I fear and pain. arrived at NHS. They are our partners. We Great things have been accomplished by would not be where we are without these all of these folks. amazing women who make time in their Because of the generosity of Omaha, we busy lives to make a difference for the have grown from a small, inadequate, run- animals. -

Winkie Dm 1 Pdsa Dickin Medal Winkie Dm 1

WINKIE DM 1 PDSA DICKIN MEDAL WINKIE DM 1 “For delivering a message under exceptionally difficult conditions and so contributing to the rescue of an Air Crew while serving with the RAF in February, 1942.” Date of Award: 2 December 1943 WINKIE’S STORY Carrier pigeon, Winkie, received the first PDSA Dickin Medal from Maria Dickin on 2 December 1943 for the heroic role she played in saving the lives of a downed air crew. The four-man crew’s Beaufort Bomber ditched in the sea more than 100 miles from base after coming under enemy fire during a mission over Norway. Unable to radio the plane’s position, they released Winkie and despite horrendous weather and being covered in oil, she made it home to raise the alarm. Home for Winkie was more than 120 miles from the downed aircraft. Her owner, George Ross, discovered her and contacted RAF Leuchars in Fife to raise the alarm. “DESPITE HORRENDOUS WEATHER AND BEING COVERED IN OIL SHE MADE IT HOME ...” Although it had no accurate position for the downed crew, the RAF managed to calculate its position, using the time between the plane crashing and Winkie’s return, the wind direction and likely effect of the oil on her flight speed. They launched a rescue operation within 15 minutes of her return home. Following the successful rescue, the crew held a celebration dinner in honour of Winkie’s achievement and she reportedly ‘basked in her cage’ as she was toasted by the officers. Winkie received her PDSA Dickin Medal a year later. -

"G" S Circle 243 Elrod Dr Goose Creek Sc 29445 $5.34

Unclaimed/Abandoned Property FullName Address City State Zip Amount "G" S CIRCLE 243 ELROD DR GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $5.34 & D BC C/O MICHAEL A DEHLENDORF 2300 COMMONWEALTH PARK N COLUMBUS OH 43209 $94.95 & D CUMMINGS 4245 MW 1020 FOXCROFT RD GRAND ISLAND NY 14072 $19.54 & F BARNETT PO BOX 838 ANDERSON SC 29622 $44.16 & H COLEMAN PO BOX 185 PAMPLICO SC 29583 $1.77 & H FARM 827 SAVANNAH HWY CHARLESTON SC 29407 $158.85 & H HATCHER PO BOX 35 JOHNS ISLAND SC 29457 $5.25 & MCMILLAN MIDDLETON C/O MIDDLETON/MCMILLAN 227 W TRADE ST STE 2250 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 $123.69 & S COLLINS RT 8 BOX 178 SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $59.17 & S RAST RT 1 BOX 441 99999 $9.07 127 BLUE HERON POND LP 28 ANACAPA ST STE B SANTA BARBARA CA 93101 $3.08 176 JUNKYARD 1514 STATE RD SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $8.21 263 RECORDS INC 2680 TILLMAN ST N CHARLESTON SC 29405 $1.75 3 E COMPANY INC PO BOX 1148 GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $91.73 A & M BROKERAGE 214 CAMPBELL RD RIDGEVILLE SC 29472 $6.59 A B ALEXANDER JR 46 LAKE FOREST DR SPARTANBURG SC 29302 $36.46 A B SOLOMON 1 POSTON RD CHARLESTON SC 29407 $43.38 A C CARSON 55 SURFSONG RD JOHNS ISLAND SC 29455 $96.12 A C CHANDLER 256 CANNON TRAIL RD LEXINGTON SC 29073 $76.19 A C DEHAY RT 1 BOX 13 99999 $0.02 A C FLOOD C/O NORMA F HANCOCK 1604 BOONE HALL DR CHARLESTON SC 29407 $85.63 A C THOMPSON PO BOX 47 NEW YORK NY 10047 $47.55 A D WARNER ACCOUNT FOR 437 GOLFSHORE 26 E RIDGEWAY DR CENTERVILLE OH 45459 $43.35 A E JOHNSON PO BOX 1234 % BECI MONCKS CORNER SC 29461 $0.43 A E KNIGHT RT 1 BOX 661 99999 $18.00 A E MARTIN 24 PHANTOM DR DAYTON OH 45431 $50.95 -

Inaugural Animals in War & Peace Medal of Bravery Ceremony November 14, 2019 the Gold Room Rayburn House Office Building

Inaugural Animals in War & Peace Medal of Bravery Ceremony November 14, 2019 The Gold Room Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC Honorary Attendees Sequence of Events (at time of printing) Pre-ceremony Video - “Ride Me Back Home” Willie Nelson - Singer and songwriter Opening Remarks The Honorable John Warner, Former United States Senator (VA) Pamela Brown - CNN Senior White House Correspondent The Honorable Don Beyer (VA-8th) Invocation Steve Janke - Chaplain of the Vietnam Dog Handlers Association The Honorable Julia Brownley (CA-26th) and the Vietnam Security Police Association March on the Colors The Honorable Sanford Bishop (GA-2nd) Young Marines - Quantico, VA National Anthem The Honorable Brendan Boyle (PA-2nd) The Honorable Judy Chu (CA-27th) Retire the Colors The Honorable Charlie Crist (FL-13th) Welcoming Remarks by Robin Hutton President, Angels Without Wings, Inc. The Honorable Ro Khanna (CA-17th) PDSA Dickin Medal Video The Honorable Sheila Jackson Lee (TX-18th) People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, Great Britain The Honorable Lucille Roybal-Allard (CA-40th) Presentation of Posthumous Medals of Bravery SSgt Reckless - Mike Mason, Served with SSgt Reckless in Korea The Honorable Albio Sires (NJ-8th) Cher Ami - Robert McKenna,VP, American Racing Pigeon Union, Inc. The Honorable Dina Titus (NV-1st) Chips - John Wren, Chips’ Owner GI Joe - Tommy DeRosa, Handler/Churchill Loft, Monmouth, NJ COL Roger Keen, Director, US Army Museums Stormy - Ron Aiello, Stormy’s Handler in Vietnam Lucca K458 - GnySgt Chris Willingham - Lucca’s