Memories, Controversies and Creativity. Introduction. Leon Wainwright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 $1.00 Gava, Which Would Practically Dium Bombers, Operating from the Western China, July 29.^.^,., Blssct The, Baltics

raiDAT, JULY M, 1144 t- 'h AveraE# Dslly Circulation t ^ L V B For ths Meath at Jane, 1M4 Manchester Evening Herald The Weather Foreeost of C. 8. Weather Bureau The final union aervlee of the Police Captain Herman O. P vt Frederick Phillips teft Isst veterans, nsxt Tussdsy svsning at Due to the tow-n meeUng Mon night f6r Sioux a ty , lows, after Chester as Speaker 8,762 day night, the meeting of the V. F, North Methodist and Second Con Schendel,' who ir chairman of the eight o’clock. Bathing Caps Showers today and tonight; Sun- gregational eburobea will be held Dog Obedience Trials to be held a 10-day furlough at his home, 382 Arthur V. Geary, Veterans’ . Member at Hw Andit 'About Town W, athedulev. on that date has been Hartford road. He was gradustad day fair and moderatelT warm; Sunday morning at 10:45 at the on the grounds of the Aetna Life On Rehabilitation Placsmsnt Ofllcsr for OonnscUcut, Thermos and Pienk Jags *4 OifeolnUoas moderate winds. canceli^ until further notice. Congregational church, when the Insurance Company in Hartford from the Chahute Field, 111.,-Army U. S. Employment Service, will paator, Rev. Dr. Ferris E. Rey tomorrow afternoon, has an Air Forces Training Comniand, Mibl Berthold Woythaler ol' Mis* Incx Sea stra n d ^ i^*®“** after taking the special purpose also address th* meeting. William and SoppHes. Manchester—’A City of Village Charm ipl« B«Ui^ Sholom, announce* nolds will praach on the subJect, nounced that Congressman Wil Edward P. Cheater, I^rector, C. -

Overview of the 1997^2000 Activity of Volca¤N De Colima, Me¤Xico

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 117 (2002) 1^19 www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Overview of the 1997^2000 activity of Volca¤n de Colima, Me¤xico V.M. Zobin a;Ã, J.F. Luhr b, Y.A. Taran c, M. Breto¤n a, A. Corte¤s a, S. De La Cruz-Reyna c, T. Dom|¤nguez d, I. Galindo d, J.C. Gavilanes a, J.J. Mun‹|¤z e, C. Navarro a, J.J. Ram|¤rez a, G.A. Reyes a, M. Ursu¤a f , J. Velasco f , E. Alatorre a, H. Santiago a a Observatorio Vulcanolo¤gico, Universidad de Colima, Av. Gonzalo de Sandoval #333, Col. Las V|¤boras, 28052 Colima, Mexico b Department of Mineral Sciences, NHB-119, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA c Instituto de Geof|¤sica, UNAM, Coyoaca¤n 04510, Me¤xico D.F., Mexico d Centro Universitario de Investigaciones en Ciencias del Ambiente, Universidad de Colima, P.O. Box 44, 28000 Colima, Mexico e Coordinacio¤n General de Investigacio¤n Cient|¤¢ca, Avenida Universidad 333, Universidad de Colima, C.P. 28040 Colima, Mexico f Consejo Estatal de Proteccio¤n Civil de Colima, 28010 Colima, Mexico Received 1 May 2001; accepted 1 November 2001 Abstract This overview of the 1997^2000 activity of Volca¤n de Colima is designed to serve as an introduction to the Special Issue and a summary of the detailed studies that follow. New andesitic block lava was first sighted from a helicopter on the morning of 20 November 1998, forming a rapidly growing dome in the summit crater. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Book of Abstracts: Studying Old Master Paintings

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE 1618 September 2009, Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London Supported by The Elizabeth Cayzer Charitable Trust STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1618 September 2009 Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London The Proceedings of this Conference will be published by Archetype Publications, London in 2010 Contents Presentations Page Presentations (cont’d) Page The Paliotto by Guido da Siena from the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena 3 The rediscovery of sublimated arsenic sulphide pigments in painting 25 Marco Ciatti, Roberto Bellucci, Cecilia Frosinini, Linda Lucarelli, Luciano Sostegni, and polychromy: Applications of Raman microspectroscopy Camilla Fracassi, Carlo Lalli Günter Grundmann, Natalia Ivleva, Mark Richter, Heike Stege, Christoph Haisch Painting on parchment and panels: An exploration of Pacino di 5 The use of blue and green verditer in green colours in seventeenthcentury 27 Bonaguida’s technique Netherlandish painting practice Carole Namowicz, Catherine M. Schmidt, Christine Sciacca, Yvonne Szafran, Annelies van Loon, Lidwein Speleers Karen Trentelman, Nancy Turner Alterations in paintings: From noninvasive insitu assessment to 29 Technical similarities between mural painting and panel painting in 7 laboratory research the works of Giovanni da Milano: The Rinuccini -

Massachusetts Inst. of Thch.) 666 P HC A9NATIF A0L AEOA, CSCD 03F Unclas

lo2 to the " NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION Contract NAS9-12334 -APOLLOPASSIVE SEISMICEXPERIMENT PARTICIPATION 'I NASA-CR-151882) LUNAR SEISMOLOGY: THE 1479-17782 INTERNAL STRUCTURE ORHE LOt Ph. Thesis (Massachusetts Inst. of Thch.) 666 p HC A9NATIF A0L AEOA, CSCD 03f Unclas 1 Januarya-19-12 -o 3.0 September .1978 G3/91' 1351 0 M. Nafi Toksbz- Principal Investigator Department of Earth and Planetar SciencesO Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 LUNAR SEISMOLOGY: THE INTERNAL STRUCTURE OF THE MOON by -Neal Rodney Goins Submitted to the Department of-Earth -and Planetary Sciences on May 24,.1978, in parti&l .flfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.. ABSTRACT, A primary goal of-the Apollo missions was the exploration and scientific study of the moon. The nature of the lunar interior is of particular interest for comparison with the earth and in studying comparative planetology. The principal experiment designed to study the lunar interior was the passive seismic experiment (PSE) included as part of the science package on missions 12, 14, 15, and 16. Thus seis mologists were provided with a uniqueopportunity ta study the seismicity and seismic characteristics of a second planetary 'bdy and ascertain if analysis methods developed on earth could illuminate the structure of the lunar interior. The lunar seismic data differ from terrestrial data in three major respects. First, the seismic sources are much smaller than on earth, so that no significant information has -been yet obtained for the 4v/ry deep lunar interior. Second, a strong, high Q scattering layer exists on the surface of the moon, resulting in very emergent seismic arrivals, long ringing-codas that obscure secondary (later arriving)-phases., and 'the-destruction of coherent dispersed surface wave trains. -

California State University Fullerton Emeriti Directory 2018

California State University Fullerton Emeriti Directory 2018 Excerpts from the Emeriti Bylaws The purpose of the Emeriti of California State University, Fullerton shall be to promote the welfare of California State University, Fullerton; to enhance the continuing professionalism of the emeriti; and to provide for the fellowship of the members Those eligible for membership shall include all persons awarded emeritus status by the President of California State University. Those eligible for associate membership shall be the spouse of any deceased Emeritus. California State University Emeritus and Retired Faculty Association The Emeriti of California State University, Fullerton are affiliated with the California State University Emeritus and Retired Faculty Association (CSU-ERFA). CSU-ERFA is the state- wide, non-profit organization that works to protect and advance the interests of retired faculty, academic administrators and staff of the CSU at the state and national level. Membership is open to all members of the Emeriti of CSUF including emeriti staff. CSU-ERFA monthly dues are very modest and are related to the amount of your 15% rebate of dues collected from CSUF members for use by our local emeriti group. We encourage all Fullerton emeriti to consider joining CSU-ERFA. For more information go to http://csuerfa.org or send email to [email protected]. CSUF Emeriti Directory August 2018 Emeriti Officers . 1 Current Faculty and Staff Emeriti . 2 Deceased Emeriti . .. 52 Emeriti by Department . 59 Emeriti Associates . 74 Emeriti Officers Emeriti Board President Local Representatives to CSU-ERFA Jack Bedell [email protected] Vince Buck [email protected] Vice President Diana Guerin Paul Miller [email protected] [email protected] Directory Information Secretary Please send changes of address and contact George Giacumakis informaiton to [email protected] [email protected] Emeriti Parking and Benefits Treasurer Rachel Robbins, Asst. -

Appendix a Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable

Appendix A Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable, or Possible Distal Ejecta Layers A.1 Introduction In this appendix we discuss the methods that we have used to recover and study ejecta found in various types of sediment and rock. The processes used to recover ejecta material vary with the degree of lithification. We thus discuss sample processing for unconsolidated, semiconsolidated, and consolidated material separately. The type of sediment or rock is also important as, for example, carbonate sediment or rock is processed differently from siliciclastic sediment or rock. The methods used to take and process samples will also vary according to the objectives of the study and the background of the investigator. We summarize below the methods that we have found useful in our studies of distal impact ejecta layers for those who are just beginning such studies. One of the authors (BPG) was trained as a marine geologist and the other (BMS) as a hard rock geologist. Our approaches to processing and studying impact ejecta differ accordingly. The methods used to recover ejecta from unconsolidated sediments have been successfully employed by BPG for more than 40 years. A.2 Taking and Handling Samples A.2.1 Introduction The size, number, and type of samples will depend on the objective of the study and nature of the sediment/rock, but there a few guidelines that should be followed regardless of the objective or rock type. All outcrops, especially those near industrialized areas or transportation routes (e.g., highways, train tracks) need to be cleaned off (i.e., the surface layer removed) prior to sampling. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

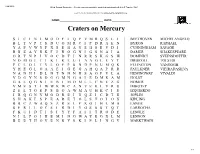

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

Feeding Villages: Foraging and Farming Across Neolithic Landscapes

Feeding Villages: Foraging and farming across Neolithic landscapes by Matthew V. Kroot A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Henry T. Wright, Chair Professor Daniel C. Fisher Professor Kent V. Flannery Professor Ian Kuijt, Notre Dame University Professor Joyce Marcus ©Matthew V. Kroot 2014 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Robin G. Nelson. ii Acknowledgments There are two parts to this dissertation work, the first being the research and the second being the writing. I would like to thank all those who labored in the field and in the lab with me to make the ‘Assal-Dhra’ Archaeological Project (ADAP) – the research program through which all the primary data of this dissertation has been derived – possible. This includes Chantel White, my co-director in the first year, as well as the paleo-environmental specialist for the duration of the project and Eliza Wallace, the project’s GIS specialist. In the first year the survey and surface collections could never have been completed without Joshua Wright who essentially designed the methodologies that we used. Additionally, Phil Graham provided enthusiastic and valuable work during this first season. Our Department of Antiquities representative, Rami Freihat, helped with fieldwork and field life in countless ways. In the second season, I had the pleasure of working with two very helpful members of the Department of Antiquities: Jamal Safi, who helped map the site of al-Khayran, and Khaled Tarawneh, who worked tirelessly for ADAP both in the field and in the bureaucracy. -

Assignment 5. SuzyWalker-Toye

Assignment 5. Suzy Walker-Toye - Student ID 510646 Contents: ● Five pages of notes (for three chapters in WHA, 1900 onwards) ● Two annotations of paintings & direct references ● One 510 word analysis & direct references ● General References for assignment 5 The reflection for this assignment is on the blog: https://westernarthistorybysuzy.wordpress.com/category/assignments/assignment-5/ Suzy Walker-Toye. Student ID 510646. A World History of Art notes Page 1 of 5 Art from 1900-1919: Political, economic or social factors 20thC revolt against naturalism. Africa in focus (colonial scandal,1904). German architects creative autonomy led to anarchy. Futurist ideas spread throughout West, aim to obliterate past society, cut short by WWI. Cézanne died. Changes to status/training of artists: Paris artistic capital for Avant-garde art. Exhibitions Paris/Russia, raised profiles. Matisse/Picasso's chief patrons wealthy Russians with public collections so Russian artists up to date. Development of materials & processes: Boccioni/Picasso's radical innovations (Futurist sculpture Manifesto/collage/ non-traditional materials/open form sculpture) underpin further developments in all cultural areas eg Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,1907. Expressionists used woodblock. Styles & movements: Impressionism ends w Monet’s almost abstract Water Lilies,1907. Dilemma of form over inner truth. Period characterised by search for new ways of looking. Naivety: Henri Rousseau, enormous/imagined jungle landscapes. Les Fauves lead by Matisse. Harmony in Red,1908 sums up style. Devoid of social comment/ strident arbitrary flat areas of colour express artists personal emotional reaction to subject/not descr representation. Derain/Vlaminck. Rouault left early, Expressionist religious anguish. German Expressionism conveyed oppressive prewar apprehension. -

Gen. Marshall Dies; Top Military Leader

)wi»W. ■ ■ -i,---- . ,y . \ Thd W i Averagd Daily Ndt Prew Run nUDAY, OCTOBER 16, 19W at D. ■- W* Fer the Weak Bnded fllanrbPBtrr twfttlws ilw alb . O et 18. 18M ■Idiaad project win b* und*r*lMd. 13,027 Th* woman’* aiucillaty of St. Mia* Dorothy Ansaldl, daught*r There will not he all th* parking, Mary** Bplaoopal Church will or Mr. xnd Mr*. Andrew Anaaldl, HearingSet Member ef the Andit apac* eaUad for under th* regula Bureau ef OIrenlatien. About Town aponaor a rummag* *al* In Ui* 138 W. Center St., ha* b*en elected tion*, tine* It 1* not thought nec- M anehm tier^A City o f VUlmgo .CAm t h i crypt of the church 'Thuraday, realdent of her dormitory at En- tlH BtpMT aub Will hold «l Mt- S eaaary in a project at.thla Oct. 3t. begli^liig at 8:S0 am. IcOti Junior Collag*, Bevarly, On Housings and there will W more'than l^ it party for member* and M*M„ where *he 1* a aenlor and ig an Png* 18) PRICE PiVE CENtB (rt*Bds toaight itartliiK at S. main building on a let. In add^ VOL. LtXIX, NO. 15 TWELVE PAGES—TV SECTION-SUBURBIA. TODAY MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, OCTOBBR IL 1M» The Newcomer*’ dub of Man- also a member of the atudenf Mon, a waiver of the 110-day atai council. Church Bids An annual department parley cheater will meet Tueaday , at 8 of. eonatnictlon date i* bef p m. In the fireplace room at the •f Aneorlcan t«ilan auxiliary will Bug*ne Sweeney.