A General Assessment of Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Annex G Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment

Cumbria County Council Draft Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Annex G Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment October 2014 Cumbria County Council Table of contents Chapter Page(s) Glossary of Acronyms 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Overview 3 1.2 Purpose of a Local Flood Risk Management Strategy 4 1.3 Requirement for a Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment 5 1.4 Summary of the key WFD Objectives 6 1.5 Other legislation 8 2. Cumbria LFRMS 9 2.1 Overview of the study area 9 2.2 Timescale 10 2.3 Objectives of the Cumbria LFRMS 11 2.4 WFD Preliminary Screening 11 2.5 Water bodies and how they are classified 14 2.6 Water quality data for the River Basin Districts 15 3. WFD Assessment 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 WFD Objectives 17 3.3 Testing the LFRMS against WFD Objectives 18 3.4 Pressures on the water environment 20 4. Conclusion 26 5. References 27 Figures 1 Designated conservation sites in Cumbria 8 2 Cumbria County Council administrative area 9 3 Named water bodies wholly or partially within the Cumbria LFRMS area 12 4 River Basin Districts in Cumbria 16 5 WFD assessment objectives 18 6 High level WFD assessment 19 7 Pressures on the water environment 20 8 Assessment of the Cumbria LFRMS measures and actions 21 Glossary of Acronyms AWB Artificial Water Bodies BAU Business as Usual LDNP Lake District National Park EU European Union LLFA Lead Local Flood Authority FWMA Flood and Water Management Act 2010 LFRMS Local Flood Risk Management Strategy GCS Good Chemical Status RBMP River Basin Management Plan GEP Good Ecological Potential SSSI Site of Special Scientific Interest GES Good Ecological Status SAC Special Area of Conservation HMWB Heavily Modified Water Bodies SPA Special Protection Area WFD Water Framework Directive Serving the people of Cumbria Annex G Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment 1. -

Lakes Big Swims Trip Notes

` Lakes Big Swims Trip Notes TRIP OVERVIEW The Lake District is home to over 80 lakes, meres, waters, and tarns making it a great location for open water swimming. On this short escape, we offer the opportunity to do some longer swims on what we think are four of the best lakes in the area. The days are packed as we swim the entire length of Derwent Water and Wast Water and swim across Grasmere and Ullswater. This trip is a fabulous opportunity to spend a few days not only exploring the different areas of the Lake District from a swimming perspective, but also experiencing the uniqueness of each lake. Swimmers will be escorted by experienced swim guides and qualified canoeists during all swims. Our accommodation is located on the shores of the water at Grasmere, right across the road from Wordsworth’s Dove Cottage. WHO IS THIS TRIP FOR? This trip is a combination of lake length swims as well as some long width crossings. Most swims are between 4-5kms, so the trip is best suited to those who fancy these types of distances. Although challenging, these swims are some of the most spectacular anywhere in the Lakes. LOCATION SUMMARIES Wast Water Wast Water is perhaps the most awe-inspiring of all the lakes and the deepest in England. Surrounded by the mountains of Red Pike, Kirk Fell and Great Gable, the peak of Scafell Pike, England’s highest mountain is our target as swim the length of this Water. Derwent Water Derwent Water is fed by the River Derwent with a catchment area in the high fells surrounded to its west rise by the fells of Cat Bells and to its east, the fantastic viewpoint of Friar's Crag, jutting into the lake. -

River Lodge Under Loughrigg, Ambleside, LA22 9LN

River Lodge Under Loughrigg, Ambleside, LA22 9LN Price £745,000 www.matthewsbenjamin.co.uk River Lodge Under Loughrigg, Ambleside Overlooking River Rothay this impressive four bedroom, four bathroom house with spacious reception rooms is enviably located only a short riverside walk away from the well known village of Ambleside. This delightful country house has been immaculately and sympathetically restored and extended over recent years by the current vendors and they have created a luxurious property in an idyllic location. Ample parking, natural sloping gardens with a small stream and panoramic views towards the surrounding countryside. Currently an extremely successful 4* (gold) holiday let with Lakelovers, generating circa £53,000 per annum. River Lodge is set in a gently elevated position above the River Rothay approximately 1.5 miles from the popular Lakeland town of Ambleside offering a variety of amenities including shops, restaurants, bank and cafes etc. There are a wide variety of walks from the doorstep. www.matthewsbenjamin.co.uk Head north out of Ambleside on the Rydal Road for approximately 1½ miles turning left at Rydal over the bridge. Continue through the paddock and then turn right up the private drive, veering left over the private cattle grid up the gently sloping drive . Fully glazed front door into a lovely wide hallway with a slate floor with under floor heating. Open oak spindle staircase with inset lighting. Telephone point. Cloakroom with fuse box. Internal door leading to useful space providing washer/dryer. An excellent drying room with Vaillant boiler, inset lighting, base unit, extractor and under floor heating with a slate floor. -

Lake District: Wandern

Alle Infos zu dieser Reise finden Sie hier LAKE DISTRICT: WANDERN Ort: Vereinigtes Königreich Reisedauer: 8 Tage Teilnehmerzahl: 5 - 16 Schwierigkeit: Mittel Reiseart: Wander- und Trekkingreisen, Gruppenreise LAKE DISTRICT Auf Ihrer 8-tägigen Standortreise lernen Sie den fabelhaften Lake District mit all seinen Facetten kennen. Die Landschaft scheint wie aus dem Bilderbuch: zerklüftete Berge, grüne Hügel und schimmernde Seen soweit das Auge reicht. Viele Dichter und Schriftsteller fanden an diesem wundervollen Flecken Erde die Inspiration für ihre Werke, und besonders die Romantiker, wie William Wordsworth, verfielen der schönen Natur. Lassen auch Sie sich von dem Zauber der Seen in den Bann ziehen und erleben Sie zu Fuß die Schönheit der Region. Inklusivleistungen kleine Gruppe mit max. 16 Gästen garantierte Durchführung ab 5 Gästen 1 / 7 Linienflug (Economy) mit Lufthansa von Frankfurt/M. (FRA) nach Manchester (MAN) und zurück (inkl. Steuern & Gebühren). Platzangebot begrenzt. Aufpreise möglich. Weitere Abflugorte in Deutschland, Österreich & der Schweiz. Rail&Fly-Ticket der Deutschen Bahn: 71 € (2. Kl.); bitte bei Anmeldung mitbuchen. Transfers & Transporte in klimatisierten Fahrzeugen 7 Nächte im Doppelzimmer (DZ) mit Bad oder Dusche/WC im Hotel „Windermere Hydro“ Mahlzeiten lt. Programm Programm wie beschrieben inkl. Eintrittsgelder ständige, deutschsprachige Reiseleitung Zusatzleistungen Doppelzimmer zur Alleinbenutzung 465€ Rail&Fly-Ticket der Deutschen Bahn; bitte bei 71€ Anmeldung mitbuchen (2. Klasse Reiseverlauf 1. Ihr 3-Sterne-Hotel „Windermere Hydro“ Das viktorianische Hotel aus dem 19. Jh. punktet mit einem Charme, der Tradition und Moderne verbindet. Das Haus liegt in dem schönen Ort Bowness-on- Windermere, mitten im Herzen des Lake Districts. Genießen Sie den atemberaubenden Ausblick auf den größten natürlichen See in ganz England, Lake Windermere. -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D. -

To View PDF Article from Black & White Photography

SPONSORED BY SPONSORED BY TECHNIQUE All images © Chris Routledge THE BIG PICTURE The SIGMA SD Quattro is a truly versatile camera that can deliver exceptional black & white pictures. But it also offers a superb widescreen option, as Chris Routledge explains. or the past two northern England. government’s Flood Information differently, not only because the collection, but when I had the Hasselblad X-Pan film camera years I have been I have heard passing tourists Service says flooding is possible. scene itself changes, but also opportunity to visit the Rothay ‘Actually being able to compose the frame and close to the modern 64 photographing a compare this stretch of the I began by documenting the because you see it differently with Sigma’s SD Quattro H and widescreen cinema and classic 65 B+W in the aspect ratio you want, while on B+W short section of the Rothay in summer to a Cotswold strange effects of the flood: over time. While working on my 18-35mm f/1.8 lens, I wondered Cinemascope formats. Being river Rothay in the stream. But on 5 December, fences tightly woven with grass Rothay project I’ve used both whether an unfamiliar camera location, is very liberating.’ able to look through the Lake District, roughly 2015, the Rothay transformed and leaves, large stones flung film and digital cameras to might help me find a new viewfinder and see the Fbetween the eastern end of into a raging giant 50m wide, across sheep pasture and turf document the changing perspective on familiar territory. In theory, this should give a square viewfinder of my widescreen sweep of river I was Rydal Water, and the historic carrying branches and debris rolled up like a carpet by the landscape, to capture the In particular, I wanted to explore similar look, regardless of the Yashica, because of the way hoping to capture, or framing Ambleside stepping stones. -

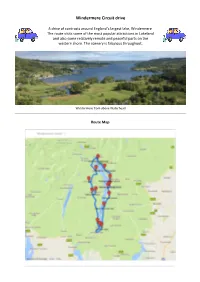

Windermere Circuit Drive

Windermere Circuit drive A drive of contrasts around England’s largest lake, Windermere. The route visits some of the most popular attractions in Lakeland and also some relatively remote and peaceful parts on the western shore. The scenery is fabulous throughout. Windermere from above Waterhead Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 2.1 miles Brockhole Visitor Centre N 54.40120, W 2.93914 4.3 miles Rayrigg Meadow picnic site N 54.37897, W 2.91924 5.3 miles Bowness-on-Windermere N 54.36591, W 2.91993 7.6 miles Blackwell House N 54.34286, W 2.92214 9.5 miles Beech Hill picnic site N 54.32014, W 2.94117 12.5 miles Fell Foot park N 54.27621, W 2.94987 15.1 miles Lakeside, Windermere N 54.27882, W 2.95697 15.9 miles Stott Park Bobbin Mill N 54.28541, W 2.96517 21.0 miles Esthwaite Water N 54.35029, W 2.98460 21.9 miles Hill Top, Near Sawrey N 54.35247, W 2.97133 24.1 miles Hawkshead Village N 54.37410, W 2.99679 27.1 miles Wray Castle N 54.39822, W 2.96968 30.8 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Waterhead car park, Ambleside Coordinates: N 54.42116, W 2.96284 Slightly south of Ambleside town, Waterhead has a lovely lakeside setting with plenty of attractions. Windermere lake cruises call at the jetty here and it is well worth taking a trip down the lake to Bowness or even Lakeside at the opposite end of the lake. -

Westmorland. .Ambleside

.DIRECTORY.J WESTMORLAND. .AMBLESIDE. 13 AMELESIDE, a. small but ancient market town, and J acter. There is also 8 small library of about 800 formerly a township in Grasmere and Windermere volumes and a. rea.din~ room supplied with daily and parishes, was constituted Il. parish 15th September, 1863, weekly papers, magazIDes &c. which is open free to and is the head of a petty sessional division and county visitors. court district, 5 miles north-west from Windermere The Ambleside and District Conservative Club, in the station, on the London and North Western railway, 4 Market place, has well-appointed billiard, reading and 80Uth-east from Grasmere and Rydal lakes, 13 north- smoke rooms, with the usual offices j visitors are ad west from Kendal, 25 south-west from Appleby and 275 mitted upon payment of IS. per week. from London, in the Northern division of the county, .Fairs are held here on Whit Wednesday for cattle j Rendal ward, rural deanery of Ambleside, archdeaconry October 13th for sheep j and October 29th for cattle. of Westmorland and diocese of Carlisle. The market day is on Wednesday. The town is seated on a declivity at the head of Win- The principal hotels are the Queen's, the Salutation dermere lake, in the beautiful vale of Bothay, and and the Windermere Waterhead hotel; the latter stands commands fine views of the lake and valley, the parks of at the head of the lake, and affords a fine general view. Rydal and Brathay, and the varied scenery at the foot The ~echanics' Institute, in the Market place, was of Wansfell Pike and Loughrigg .Fell. -

Annex G Water Framework Directive Assessment Pdf 1991Kb

Cumbria County Council Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Annex G Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment March 2015 Cumbria County Council Table of contents Chapter Page(s) Glossary of Acronyms 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Overview 3 1.2 Purpose of a Local Flood Risk Management Strategy 4 1.3 Requirement for a Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment 5 1.4 Summary of the key WFD Objectives 6 1.5 Other legislation 8 2. Cumbria LFRMS 9 2.1 Overview of the study area 9 2.2 Timescale 10 2.3 Objectives of the Cumbria LFRMS 11 2.4 WFD Preliminary Screening 11 2.5 Water bodies and how they are classified 14 2.6 Water quality data for the River Basin Districts 15 3. WFD Assessment 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 WFD Objectives 17 3.3 Testing the LFRMS against WFD Objectives 18 3.4 Pressures on the water environment 20 4. Conclusion 26 5. References 27 Figures 1 Designated conservation sites in Cumbria 8 2 Cumbria County Council administrative area 9 3 Named water bodies wholly or partially within the Cumbria LFRMS area 12 4 River Basin Districts in Cumbria 16 5 WFD assessment objectives 18 6 High level WFD assessment 19 7 Pressures on the water environment 20 8 Assessment of the Cumbria LFRMS measures and actions 21 Glossary of Acronyms AWB Artificial Water Bodies LDNP Lake District National Park BAU Business as Usual LLFA Lead Local Flood Authority EU European Union LFRMS Local Flood Risk Management Strategy FWMA Flood and Water Management Act 2010 RBMP River Basin Management Plan GCS Good Chemical Status SSSI Site of Special Scientific Interest GEP Good Ecological Potential SAC Special Area of Conservation GES Good Ecological Status SPA Special Protection Area HMWB Heavily Modified Water Bodies SuDS Sustainable Drainage System WFD Water Framework Directive Serving the people of Cumbria Annex G Water Framework Directive (WFD) Assessment 1. -

Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Directions 2009

The River Basin Districts Typology, Standards and Groundwater threshold values (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Directions 2009 The Secretary of State and the Welsh Ministers, with the agreement of the Secretary of State to the extent that there is any effect in England or those parts of Wales that are within the catchment areas of the rivers Dee, Wye and Severn, in exercise of the powers conferred by section 40(2) of the Environment Act 1995(a) and now vested in them(b), and having consulted the Environment Agency, hereby give the following Directions to the Environment Agency for the implementation of Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy(c): Citation and commencement and extent 1.—(1) These Directions may be cited as the River Basin Districts Typology, Standards and Groundwater threshold values (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Direction 2009 and shall come into force on 22nd December 2009. Interpretation 2.—(1) In these Directions— ―the Agency‖ means the Environment Agency; ―the Groundwater Directive‖ means Directive 2006/118/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration(d); ―the Priority Substances Directive‖ means Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on environmental quality standards in the field of water policy(e); ―threshold value‖ has the same meaning as in the Groundwater Directive; and ―the Directive‖ means Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23rd October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. -

7. Analyses of Streamwaters in the Catchment of Windermere (1975-1978), Including Kirkstone Beck

Analysis of stream waters in the catchment of Lake Windermere (1975-1978), England [Dataset] Item Type other Authors Carrick, T.R.; Sutcliffe, D.W. Publisher Freshwater Biological Association Download date 28/09/2021 17:08:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/22854 7. ANALYSES OF STREAMWATERS IN THE CATCHMENT OF WINDERMERE (1975-1978), INCLUDING KIRKSTONE BECK CONTENTS Pages Sampling sites 75 Great Langdale Beck and River Brathay B1-B5 77 Stock Ghyll Sl-S6 92 Raise Beck, River Rothay and tributaries Rl-R12 104 Easedale Beck and tributaries El-E3 135 Kirkstone Beck K1-K2 145 Troutbeck and tributaries T1-T7 150 Smooth Beck H1 156 Black Beck H2 161 Ford Wood Beck - Outgate H3 164 Table 3. Sampling sites, map references and width of streams (in metres). Number Name Map Reference Width B1 Great Langdale Beck at Middle Fell Farm NY 284060 10.5 B2 Great Langdale Beck at Chapel Stile NY 322052 10.5 B3 River Brathay at Fell Foot Farm NY 300032 3 B4 River Brathay at Colwith Bridge NY 330030 12 B5 River Brathay - bottom NY 365034 15 S1 Stock Ghyll above Kirkstone Inn NY 401082 1 S2 Stock Ghyll draining from Kirkstone Pass NY 398078 1 S3 Stock Ghyll draining from Raven Crag NY 398078 1.8 S4 Stock Ghyll tributary from Kirkstone Quarry NY 395070 0.6 S5 Stock Ghyll above Ambleside NY 382046 8 S6 Stock Ghyll - bottom NY 372046 4 R1 Raise Beck above Dunmail Raise NY 328117 2 R2 Raise Beck below Dunmail Raise NY 329110 3.5 R3 Raise Beck at Gill Foot NY 332096 3.5 R4 Green Burn at Gill Foot NY 332096 4.5 R5 Raise Beck at Low Mill Bridge NY 334092 7 R6 Tongue Gill at Low Mill Bridge NY 335092 4.5 R7 River Rothay at Butharlyp Howe NY 336081 9.5 R8 River Rothay above input of Allcock Tarn NY 339075 10 R9 Rydal Beck - bottom NY 367058 6 R10 Scandale Beck - bottom NY 372047 4 R11 River Rothay above Rothay Bridge NY 372044 10.5 R12 R. -

Walks from Our Door. Ambleside to Rydal Water Via the Coffin Route, Back Along Under Loughrigg

Walks from our door. Ambleside to Rydal water via the coffin route, back along under loughrigg. This walk is a low level, therefore relatively flat. It takes in some beautiful views across the valley, a choice of either tea rooms and pub for lunch a lake and historic houses. 1) From our front door, walk up the road towards Rattle Ghyll fine foods, at the top of the road turn left walking past The Apple pie Café and the iconic Bridge House. Carry on this road until you get to Rydal Lodge (Between the Apple Pie and Bridge House you will have gone over Stock Ghyll, on the other side of the main road on the bridge is a marker that shows above stock and below stock, anyone who lived above stock was buried in Grasmere and their coffins were carried by the women along the coffin route) 2) At Rydal lodge cross over the main road, through the gate that leads to the coffin route and walk along it enjoying the views, there are normally cows and sheep grazing in the meadows on either side of the path. When you reach Rydal Hall there is a choice of gate and stile. (Rydal Hall is currently used as a spiritual retreat, there is a tearoom here in the old schoolhouse, and some stunning gardens, which include a Victorian Grot as part of their quiet garden and a sculpture trail in the wooded area which takes you past the game larder and ice house.) 3) From the tea rooms, carry on the coffin route and you will very shortly meet a small lane, just at the top of this is Rydal Mount, the home of William Wordsworth, this currently houses a museum, he was a keen gardener so his gardens are well worth stopping off for, and they do a great cream tea.